Validating Redox Reaction Mechanisms: A Guide to Modern Experimental Approaches for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the current experimental approaches for validating redox reaction mechanisms.

Validating Redox Reaction Mechanisms: A Guide to Modern Experimental Approaches for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the current experimental approaches for validating redox reaction mechanisms. It covers the foundational principles of redox biology, explores advanced methodological techniques including in operando analysis and computational modeling, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents frameworks for the rigorous validation and comparative analysis of redox pathways. By synthesizing the latest research, this resource aims to equip scientists with the practical knowledge needed to accurately elucidate redox mechanisms, which is critical for understanding disease pathogenesis and developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Core Principles of Redox Biology and Signaling Pathways

Defining Redox Homeostasis and its Role in Cellular Function

Redox homeostasis is defined as the dynamic maintenance of the balance between reducing and oxidizing reactions within cells [1]. This equilibrium is not a static state but a highly responsive system that continuously senses changes in redox status and realigns metabolic activities to restore balance [1]. The term "redox" originates from "reduction" and "oxidation," describing chemical processes involving electron transfer between reactants [2]. In biological systems, this balance is crucial for normal cellular function, with disruptions implicated in numerous pathological conditions [3].

The significance of redox homeostasis extends across virtually all physiological processes, including cellular signaling, metabolism, immune responses, development, and cell death [1]. This guide objectively compares the experimental approaches and mechanistic insights driving contemporary redox research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured analysis of current methodologies and their applications in validating redox reaction mechanisms.

Foundational Concepts of Cellular Redox Homeostasis

Defining the Redox Balance

At its core, redox homeostasis represents an equilibrium between pro-oxidant generation and antioxidant defense systems [4]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide (●O₂⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radical (HO●), are generated through aerobic metabolism primarily in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, with deliberate production also occurring via NADPH oxidases [1] [3]. These ROS are counterbalanced by sophisticated antioxidant systems, including enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), as well as small molecular antioxidants [2].

The concept of "oxidative stress" was formally defined in 1985 as an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants in favor of the former [3]. This understanding has since evolved to recognize two distinct subcategories: oxidative eustress (beneficial, physiological signaling at low ROS levels) and oxidative distress (damaging effects at high ROS concentrations) [4] [3]. The redox state of a cell influences fundamental processes including proliferation, differentiation, and death, with proliferating cells typically maintaining a more reduced state compared to aged or differentiated cells [5].

Key Molecular Players

The following table summarizes the principal components involved in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis:

Table 1: Key Molecular Systems in Redox Homeostasis

| Component Category | Specific Elements | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive Species | Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), Superoxide (●O₂⁻), Hydroxyl radical (HO●) | Signaling molecules at low concentrations; cause oxidative damage at high concentrations [1] [3] |

| Major Antioxidant Systems | Glutathione (GSH), Thioredoxin (Trx), NADPH-regenerating systems | Maintain reducing environment; reverse oxidative protein modifications [1] |

| Transcription Factors | NRF2 (master regulator), AP-1, HO-1 | Regulate expression of antioxidant genes; cellular defense coordination [1] [2] |

| Redox-Sensitive Amino Acids | Cysteine thiols, Methionine | Reversible oxidation regulates protein function; molecular redox switches [4] [2] |

Comparative Analysis of Redox Research Methodologies

Analytical Techniques for Assessing Redox Status

Researchers employ diverse methodological approaches to investigate redox homeostasis, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The following table provides a comparative overview of key experimental platforms:

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Approaches in Redox Research

| Methodology | Key Applications | Technical Advantages | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics (e.g., Cys-reactive phosphate tag) | Comprehensive mapping of reversible cysteine oxidation across proteome [4] | High specificity and sensitivity; enables system-wide analysis [4] | Technically complex; requires specialized instrumentation and expertise |

| High-Throughput Immunoassays (ALISA, RedoxiFluor) | Target-specific quantification of cysteine oxidation in human tissues [4] | Cost-effective; accessible; compatible with standard laboratory equipment [4] | Limited to predefined targets; potential antibody specificity issues |

| Fluorescent Probes (Dihydroethidium, MitoSOX) | Estimation of cellular and mitochondrial superoxide production [4] | Relatively simple implementation; live-cell imaging capability | Non-specific oxidation products complicate interpretation [4] |

| Quantum Chemical Calculations (Hybrid DFT) | Predicting mechanisms of redox-active metalloenzymes [6] [7] | Provides atomic-level mechanistic insights; predictive capability | Computationally intensive; requires validation with experimental data |

| Square-Wave Voltammetry | Study of surface redox reactions involving adsorbed particles [8] | Powerful tool for thermodynamic and kinetic characterization | Primarily applicable to in vitro systems with limited biological context |

The NRF2-KEAP1 Signaling Pathway

The NRF2-KEAP1 system represents a crucial cellular defense mechanism against oxidative stress. The following diagram illustrates this canonical redox signaling pathway:

Experimental Workflow for Redox Proteomics

Contemporary redox research increasingly employs systematic approaches to investigate cysteine modifications. The following workflow represents a cutting-edge proteomic strategy:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogs fundamental reagents and their applications in redox biology research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Redox Homeostasis Investigations

| Research Reagent | Primary Function | Specific Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| N-acetylcysteine (NAC) | Thiol-containing antioxidant; precursor to glutathione [1] | Experimental antioxidant intervention; metal-chelating properties [1] |

| MitoSOX | Mitochondria-targeted fluorescent dye | Detection of mitochondrial superoxide production [4] |

| Antibodies for Oxidative Damage Markers | Immunodetection of specific oxidation products | Protein carbonyls (protein oxidation), 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (DNA oxidation), 4-hydroxynonenal (lipid peroxidation) [4] |

| Dehydroascorbate (DHA) | Oxidized form of vitamin C; modulates NRF2 response | Experimental intervention in models of oxidative damage [1] |

| Cysteine-reactive Probes (e.g., maleimide reporters) | Labeling and detection of redox-sensitive cysteine residues | ALISA and RedoxiFluor assays for quantifying protein thiol oxidation [4] |

| NADPH/NADP+ Assay Kits | Quantification of NADPH/NADP+ ratio | Assessment of cellular redox capacity and antioxidant defense status [2] |

Redox Homeostasis in Physiology and Disease Mechanisms

Developmental Processes

Redox regulation plays a critical role throughout development, with spatiotemporal redox interactions guiding fundamental processes [1]. In plants, the interplay between phytohormones, redox signaling, and metabolism dynamically regulates cell growth and division [1]. Differences in cytosolic and nuclear ROS levels control apical root growth through stem cell renewal and differentiation, while glutathione predominantly regulates primary root development [1].

In mammalian systems, developmental transitions involve marked redox shifts. During the transition to blastocyst stage, ATP production switches from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, reflecting a shift to a more reduced state [1]. Glutathione levels decrease during oocyte maturation and are associated with favorable fertilization and embryonic development outcomes [1]. Notably, constant NRF2 activation proves postnatally lethal in mice, demonstrating the exquisite sensitivity of developmental processes to redox balance [1].

Neural Stem Cell Regulation

In the nervous system, redox balance determines neural stem and progenitor cell (NPC) fate decisions [5]. NPCs responsible for normal neural tissue turnover display redox states that vary with their proliferation status—young/proliferating cells maintain more reduced redox balances, while differentiation leads to a more oxidized state [5]. ROS-mediated changes activate downstream signaling by modulating tyrosine kinases and concurrently inactivating phosphatases, optimizing cellular responses to growth factors like EGF and bFGF [5].

Disease Pathogenesis

Redox dysregulation contributes to numerous pathological conditions through two primary mechanisms: direct oxidative damage to biomolecules and aberrant redox signaling [2]. Diseases like atherosclerosis, radiation-induced lung injury, and paraquat poisoning are directly attributed to redox imbalances [2]. In contrast, conditions including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, type II diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer involve redox signaling as an indirect contributor to disease progression through complex signal transduction pathways [2].

Genomic instability represents a significant consequence of redox imbalance, with ROS inducing DNA missense mutations, truncation mutations, and strand breaks [2]. Additionally, redox signaling finely regulates DNA repair proteins through redox modifications of critical cysteine residues, creating a double-edged relationship between oxidative stress and genomic integrity [2].

Computational Approaches to Redox Mechanism Elucidation

Quantum Chemical Frameworks

Quantum chemical approaches, particularly density functional theory (DFT) with systematically optimized exact exchange (typically 15%), have revolutionized the study of redox-active metalloenzyme mechanisms [6] [7]. These methods employ large cluster models (150-300 atoms) representing enzyme active sites, with geometries optimized using double zeta basis sets with polarization functions [6]. More accurate energies are subsequently obtained through single-point calculations with larger basis sets, incorporating dispersion corrections and solvent effects from the protein environment [6].

This systematic DFT approach has generated strongly predictive results for biologically crucial systems including photosystem II, nitrogenase, and cytochrome c oxidase [6] [7]. For the Mn₄Ca complex in photosystem II, each 1% change in the exact exchange fraction alters the Mn(III) to Mn(IV) redox energy by approximately 1 kcal/mol, demonstrating the method's sensitivity and the importance of parameter optimization [7].

Experimental-Computational Synergy

The integration of computational and experimental approaches has proven particularly powerful in elucidating redox mechanisms. In nitrogenase research, DFT calculations challenged the experimentally proposed structure of the E4 state, demonstrating that the suggested configuration failed to reproduce the near-isoenergetic transition observed experimentally during H₂ elimination and N₂ binding [7]. This synergy between computation and experiment drives mechanistic refinement, with computational predictions guiding experimental design and experimental results validating and refining theoretical models.

The investigation of cellular redox homeostasis continues to evolve with methodological advancements enabling increasingly precise assessments of redox states and oxidative modifications. Future progress will necessitate developing precise assessment methods for redox homeostasis, rational selection of oxidative modulators based on disease characteristics, optimization of delivery systems, and creation of precise interventions tailored to specific pathological contexts [9]. The emerging field of precision redox medicine aims to remedy limitations of traditional broad-spectrum antioxidants by leveraging context-specific understanding of redox signaling and targeting specific cysteine residues in redox-sensitive proteins [4] [2]. As these approaches mature, they promise more effective therapeutic strategies for the myriad diseases characterized by redox imbalance.

Cellular redox homeostasis represents a fundamental state in which the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is balanced by antioxidant defenses, enabling ROS to function as crucial signaling molecules while preventing oxidative damage [2] [10]. This delicate equilibrium is maintained by sophisticated systems: endogenous ROS generated primarily through mitochondrial respiration and dedicated enzymes like NADPH oxidases (NOX), and antioxidant defenses orchestrated by the transcription factor Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (NRF2) [2] [11]. Disruption of this balance is implicated in the pathogenesis of a wide spectrum of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular conditions, and chronic inflammatory diseases [2] [11]. This guide objectively compares the core components of the redox system and details the experimental approaches essential for validating their complex interaction mechanisms in biomedical research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

ROS constitute a group of oxygen-derived, highly reactive molecules and free radicals with distinct chemical properties, sources, and biological impacts. Their roles range from essential physiological signaling to pathogenic oxidative damage.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Reactive Oxygen Species

| ROS Type | Chemical Symbol | Primary Cellular Sources | Reactivity & Half-Life | Primary Biological Roles & Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide Anion | O₂•⁻ | Mitochondrial ETC, NOX enzymes [12] [11] | Moderate reactivity; short half-life [12] | Precursor to most other ROS; signaling; can form peroxynitrite with NO [12] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | H₂O₂ | Superoxide dismutation, NOX4/DUOX [12] | Less reactive; diffusible; longer half-life [13] | Key redox signaling molecule [13]; regulates growth, differentiation [12] |

| Hydroxyl Radical | •OH | Fenton/Haber-Weiss reactions [12] [11] | Extremely reactive; very short half-life [11] | Extensive oxidative damage: DNA strand breaks, lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation [12] [11] |

| Lipid Peroxyl Radical | LO₂• | Lipid peroxidation chain reactions [12] [11] | Reactive; propagates chain reactions [12] | Membrane damage; generates reactive aldehydes (e.g., 4-HNE, MDA) [11] |

The Antioxidant Defense Network and the Master Regulator NRF2

To counteract ROS, cells employ a multi-layered antioxidant defense system. The first line comprises enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), which directly neutralize ROS [2] [10]. A second line involves systems for recycling and synthesizing antioxidants, such as glutathione (GSH) and thioredoxin (TXN) [2]. The NRF2 pathway serves as the master regulator of the cellular antioxidant response [2] [14].

The NRF2-KEAP1 Signaling Pathway

Under basal conditions, NRF2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by its repressor, KEAP1, which targets NRF2 for constant proteasomal degradation [14]. Upon oxidative stress, specific cysteine residues in KEAP1 are modified, halting NRF2 degradation. NRF2 then translocates to the nucleus, binds to Antioxidant Response Elements (ARE) in the promoter regions of its target genes, and activates the transcription of a vast network of cytoprotective genes [2] [14]. These include antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SOD, catalase, heme oxygenase-1), and proteins involved in glutathione synthesis and drug detoxification [2] [14].

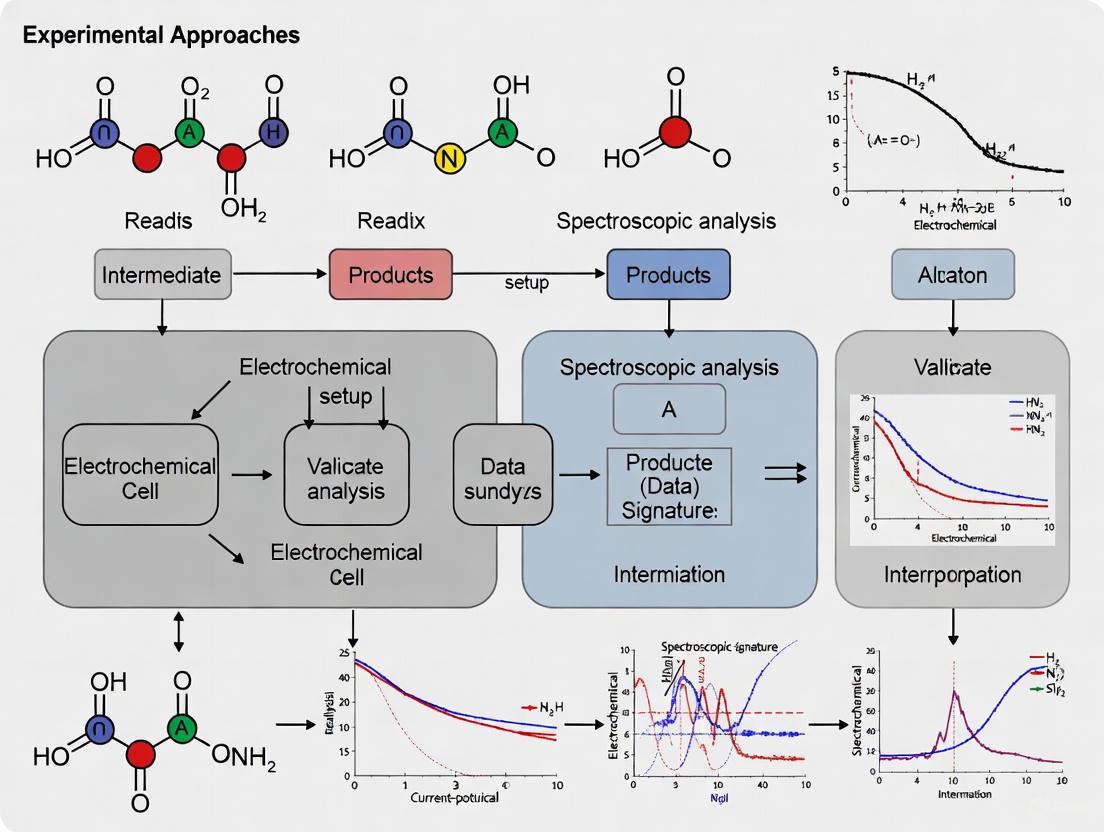

Experimental Approaches for Validating Redox Mechanisms

Validating the roles and interactions of ROS, antioxidants, and the NRF2 pathway requires a combination of specific, quantitative methodologies. The workflow below outlines a logical progression for investigating redox signaling.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Intracellular ROS Measurement

Method: Flow Cytometry using H₂DCFDA (2',7'-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate). Principle: Cell-permeable H₂DCFDA is deacetylated by intracellular esterases and then oxidized primarily by H₂O₂ to the fluorescent DCF, which is quantified [12]. Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and wash cells in PBS. Adjust cell density to 0.5-1 x 10⁶ cells/mL in pre-warmed PBS or culture medium.

- Staining: Load cells with 5-20 µM H₂DCFDA for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Stimulation & Analysis: Expose cells to the experimental stimulus (e.g., H₂O₂, TNF-α, drug compound) for a defined period. Analyze fluorescence immediately using a flow cytometer (Ex/Em ~488/525 nm).

- Controls: Include unstained cells and a positive control (e.g., cells treated with 100-500 µM H₂O₂ for 30 min).

Protocol for NRF2 Pathway Activation Analysis

A. Nuclear Translocation Assay (Immunofluorescence) Principle: Visualize the movement of NRF2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus upon activation. Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Seed cells on glass coverslips and treat with an NRF2 activator (e.g., sulforaphane, 5-20 µM) or test compound for 2-6 hours.

- Fixation & Permeabilization: Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, then permeabilize with 0.1-0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min.

- Staining: Incubate with a primary antibody against NRF2, followed by a fluorescently-labeled secondary antibody. Counterstain nuclei with DAPI.

- Imaging: Analyze using a fluorescence or confocal microscope. Nuclear accumulation of NRF2 signal indicates pathway activation.

B. Quantitative Gene Expression of NRF2 Targets (RT-qPCR) Principle: Measure the mRNA levels of canonical NRF2 target genes as a functional readout of its activity. Procedure:

- Treatment & RNA Extraction: Treat cells and extract total RNA using a commercial kit.

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe 0.5-1 µg of RNA into cDNA.

- qPCR: Perform qPCR using primers for NRF2 target genes (e.g., HMOX1, NQO1, GCLC) and housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB).

- Data Analysis: Calculate fold-change in gene expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method relative to untreated controls.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Redox Biology Research

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Key Function in Experiments | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| H₂DCFDA | Fluorescent Probe | Detects general cellular ROS levels, particularly H₂O₂ [12] | Flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy for oxidative stress |

| MitoSOX Red | Fluorescent Probe | Specifically detects mitochondrial superoxide [12] | Assessing mitochondrial-specific ROS production |

| Anti-NRF2 Antibody | Antibody | Detects NRF2 protein expression and localization | Western blot, immunofluorescence (nuclear translocation) |

| Sulforaphane | Small Molecule Agonist | Potent inducer of NRF2 signaling by modifying KEAP1 cysteines [2] | Positive control for NRF2 pathway activation experiments |

| ML385 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Inhibits NRF2-ARE binding, blocking transcriptional activity | Validating NRF2-dependent effects in functional assays |

| siRNA/shRNA vs. NRF2/KEAP1 | Genetic Tools | Knocks down gene expression to establish functional necessity | Loss-of-function studies to define pathway component roles |

| 4-OI / DMF | Clinical Agonists | NRF2 activators with therapeutic relevance [15] | Testing therapeutic potential of NRF2 activation in disease models |

The interplay between ROS generation, antioxidant defenses, and the NRF2 pathway represents a dynamic and complex signaling node central to physiology and disease. A rigorous, multi-faceted experimental approach—combining quantitative ROS detection, assessment of NRF2 activation at multiple levels, and functional genetic validation—is paramount for accurately dissecting these mechanisms. This comparative guide provides a foundational framework for researchers aiming to design robust experiments, select appropriate reagents, and generate reliable data to validate hypotheses in redox biology and advance the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Redox signaling, derived from the term "reduction-oxidation," represents a fundamental chemical process governing electron transfer between molecules and serves as a critical mediator in the dynamic interactions between organisms and their external environment [2]. Under physiological conditions, cells maintain redox homeostasis through a delicate balance between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and their elimination by endogenous antioxidant systems [2] [16] [9]. This equilibrium is crucial for normal cellular function, as redox reactions accompany biological activities and enable energy acquisition through oxidative respiration, particularly within the mitochondrial respiratory chain [2].

The conceptual understanding of oxidative stress has evolved significantly since its initial definition in 1985 as a cellular imbalance between oxidants and reductants [2]. The traditional view that ROS are merely toxic metabolic byproducts has been replaced by the recognition that they function as important signaling molecules that regulate diverse biological processes through redox modifications of proteins [2] [17]. These modifications, particularly on highly reactive thiol groups in protein cysteine residues, serve as molecular switches that dynamically regulate protein structure, function, and interactions [2] [18]. The "Redox Code" established in 2015 formalized principles governing how NADH and NADPH systems regulate metabolism, how thiol switches control the redox proteome, and how redox signaling responds to environmental changes [2].

When this finely tuned redox equilibrium is disrupted, the consequences profoundly influence both the onset and progression of various diseases [2] [17] [16]. The pathogenesis can occur through two primary mechanisms: direct oxidative damage to biomolecules including nucleic acids, membrane lipids, and structural proteins; or dysregulation of redox signaling pathways, where molecules like hydrogen peroxide act as secondary messengers that aberrantly influence cellular processes [2]. This review comprehensively examines the intricate relationship between redox signaling and disease pathogenesis, compares current and emerging therapeutic strategies, details experimental approaches for investigating redox mechanisms, and provides practical guidance for researchers pursuing redox-focused drug development.

Redox Dysregulation in Disease Pathogenesis: Molecular Mechanisms and Pathways

Cellular redox status is determined by the interplay between reactive species generation and antioxidant defenses. Reactive species encompass reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and reactive sulfur species (RSS), each with distinct biological roles and signaling capabilities [17]. ROS are primarily generated through several key mechanisms: (1) the mitochondrial electron transport chain, particularly at complexes I and III; (2) NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes located at various cellular membranes; and (3) endoplasmic reticulum activity [2] [17]. Additional sources include xanthine oxidase metabolism in the cytoplasm and mitochondrial proteins such as p66shc and monoamine oxidases [17].

The NRF2-mediated antioxidant response represents the primary cellular defense mechanism against oxidative stress [2]. Under physiological conditions, NRF2 activation elevates the synthesis of key antioxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), along with essential molecules like NADPH and glutathione (GSH) [2]. The antioxidant defense system operates through multiple tiers: the first line includes SOD (which catalyzes superoxide dismutation to hydrogen peroxide), catalase, and GPx (which eliminate hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxides) [2]. The second line of defense involves NADPH-dependent systems that reduce oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and thioredoxin through glutathione reductase and thioredoxin reductase [2].

Table 1: Major Reactive Species in Redox Signaling and Their Pathophysiological Roles

| Reactive Species | Chemical Formula/Symbol | Primary Sources | Pathophysiological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide | O₂•⁻ | Mitochondrial ETC, NOX enzymes | DNA damage, enzyme inactivation, oxidative chain initiation |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | H₂O₂ | SOD activity, NOX4 | Secondary messenger, cysteine oxidation, signal transduction |

| Hydroxyl Radical | •OH | Fenton reaction | Extreme oxidant, DNA strand breaks, lipid peroxidation |

| Nitric Oxide | NO | Nitric oxide synthases | Vasodilation, inflammation, protein S-nitrosylation |

| Peroxynitrite | ONOO⁻ | NO + O₂•⁻ reaction | Protein tyrosine nitration, lipid damage, apoptosis |

| Hydrogen Sulfide | H₂S | Cystathionine metabolism | Vasodilation, anti-inflammatory, S-sulfhydration |

Redox-Sensitive Molecular Targets and Signaling Pathways

Redox signaling exerts its biological effects primarily through post-translational modifications of redox-sensitive cysteine residues in proteins [2] [16] [18]. These modifications include disulfide bond formation (S-S), S-glutathionylation (SSG), S-nitrosylation (SNO), S-sulfenylation (SOH), and persulfidation [2] [17] [18]. These reversible oxidative modifications function as molecular switches that dynamically regulate protein function, structure, and interactions in response to cellular redox changes [18]. The susceptibility of cysteine residues to redox modifications depends on their local microenvironment, accessibility, and acid dissociation constant (pKa) [18].

Redox signaling influences multiple fundamental cellular processes through both genetic and non-genetic pathways. In terms of genomic stability, oxidative stress represents a significant factor contributing to DNA damage and compromised integrity [2]. ROS can directly induce DNA missense mutations, truncation mutations, and strand breaks during replication or transcription [2]. Additionally, redox signaling finely regulates DNA repair processes through modifications of repair proteins such as ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase, which undergoes cysteine oxidation that activates its function in double-strand break repair [2].

Beyond direct genomic effects, redox signaling significantly influences epigenetic regulation, protein homeostasis, and metabolic reprogramming [2]. These non-genetic pathways allow redox signals to modulate gene expression patterns, protein degradation, and metabolic flux in response to both internal and external stressors. The integration of redox signaling across these diverse cellular processes establishes a complex network that profoundly impacts tissue and organ function, ultimately influencing disease susceptibility and progression [2].

Disease-Specific Pathogenic Mechanisms

The contribution of redox dysregulation to disease pathogenesis varies significantly across different conditions, with both primary and secondary roles. Diseases such as atherosclerosis, radiation-induced lung injury, and paraquat poisoning are directly attributed to or primarily caused by redox imbalances [2]. In contrast, conditions including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, hypertension, type II diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome are influenced indirectly by redox signaling through complex signal transduction pathways that intersect with various cellular molecular events [2].

In cardiovascular diseases, dysregulated redox signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired autophagy form an interconnected network that drives inflammatory and immune responses [17]. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to excessive ROS accumulation, which triggers inflammation, activates inflammasomes, promotes cytokine secretion, and initiates immune cell infiltration, ultimately contributing to cardiovascular injury [17]. Specific ROS sources in the cardiovascular system include NOX isoforms (NOX1, 2, 4, and 5), mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes, and xanthine oxidase [17].

In neurodegenerative diseases, oxidative damage to vulnerable central nervous system cells represents a common pathological feature [16]. The brain's high oxygen consumption, lipid-rich environment, and relatively limited antioxidant defenses render it particularly susceptible to redox imbalance [16]. Redox signaling in neurodegeneration involves post-translational modifications such as S-glutathionylation and S-nitrosylation that alter protein function and aggregation properties [16]. Promising therapeutic strategies include boosting endogenous antioxidant machinery through Nrf2 activation or modulating ROS production using NOX inhibitors [16].

In cancer, redox regulation influences multiple aspects of pathogenesis, from genomic instability in initiation to metabolic reprogramming in progression [2] [19]. Cancer cells often exhibit elevated ROS levels that promote proliferative signaling while simultaneously upregulating antioxidant systems to maintain redox balance and avoid excessive oxidative damage [2]. This delicate balancing act creates therapeutic opportunities to further disrupt redox homeostasis in malignant cells.

Comparative Analysis of Redox-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Conventional Antioxidant Approaches: Limitations and Failures

The initial therapeutic approach targeting redox dysfunction centered on broad-spectrum antioxidants, including vitamin E, vitamin C, and other compounds designed to directly scavenge reactive species [17]. This strategy emerged from the observation that oxidative damage contributes to numerous disease processes and the hypothesis that reducing ROS levels would provide therapeutic benefit [2] [17]. However, clinical trials using these nonspecific antioxidants have largely failed to demonstrate significant improvements in patient outcomes, particularly for cardiovascular diseases [17].

Several factors contribute to the failure of conventional antioxidant therapies. First, they lack specificity, simultaneously disrupting both pathological and physiological ROS signaling [17]. Second, they cannot target the main sources of ROS generation in a spatially or temporally controlled manner [17]. Third, they often fail to address the complex, multifactorial etiologies of diseases where redox imbalance represents one component of a broader pathological network [2]. The disappointing results from these trials highlighted the need for more sophisticated, targeted approaches to redox modulation that respect the physiological roles of reactive species while counteracting their pathological effects.

Emerging Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Contemporary drug development efforts focus on specifically targeting redox-sensitive proteins or regulatory pathways rather than broadly scavenging reactive species [2] [20]. These approaches aim to re-establish redox balance while preserving essential redox signaling functions. Emerging small molecule inhibitors that target specific cysteine residues in redox-sensitive proteins have demonstrated promising preclinical outcomes, setting the stage for forthcoming clinical trials [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Redox-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

| Therapeutic Approach | Molecular Targets | Mechanism of Action | Development Stage | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRF2 Activators | NRF2-KEAP1 pathway | Enhance antioxidant gene expression | Preclinical to clinical trials | Broad antioxidant induction, cytoprotective | Potential off-target effects, dosage sensitivity |

| NOX Inhibitors | NADPH oxidase isoforms | Reduce superoxide production at source | Preclinical development | Source-specific, minimal physiological disruption | Isoform selectivity challenges |

| Mitochondria-targeted Antioxidants | Mitochondrial ROS | Accumulate in mitochondria, scavenge mtROS | Early clinical trials | Organelle-specific, address primary ROS source | Limited to mitochondrial dysfunction |

| Redox-sensitive Cysteine Targeting | Specific cysteine residues | Modify redox-sensing cysteines | Preclinical | High specificity, minimal physiological disruption | Identification of critical cysteines |

| GSTO1-1 Inhibitors | Glutathione transferase | Modulate thioltransferase activity | Preclinical | Target specific redox enzyme | Potential metabolic side effects |

One promising strategy involves boosting endogenous antioxidant defenses through activation of the master regulator NRF2 [16]. This approach enhances the expression of multiple antioxidant enzymes simultaneously, providing a coordinated defensive response. Alternative strategies focus on modulating ROS production at its source using NOX inhibitors [16] or targeting specific redox-sensitive signaling molecules including kinases (AMPK, MAPKs), phosphatases (PTPs), and transcription factors (NF-κB) [20]. Unlike nonspecific ROS-scavenging therapy, the selective modulation of these redox-sensitive proteins offers a more precise and effective approach [20].

The context-dependent nature of redox signaling necessitates careful consideration of therapeutic timing, dosage, and patient selection. The same redox-modulating intervention may produce divergent outcomes depending on disease stage, cell type, and microenvironmental factors [2]. Future advances will require the development of precise assessment methods for redox homeostasis, judicious selection of oxidative modulators based on disease characteristics, rationalization of delivery systems, and creation of precise interventions that achieve optimal modulation either positively or negatively to meet therapeutic goals across different diseases [9].

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Redox Signaling Mechanisms

Redox Proteomics and Omics Technologies

Advanced mass spectrometry-based redox proteomics has revolutionized the identification and quantification of oxidative post-translational modifications (oxiPTMs) on redox-sensitive proteins [18]. These techniques enable researchers to detect previously elusive transient oxidative modifications in a physiological context, providing unprecedented insights into the functional dynamics of redox-regulated cellular processes [18]. Key methodological advancements include enrichment strategies such as Isotope-Coded Affinity Tags (ICATs), Resin-Assisted Capture (RAC), and the Biotin-Switch Assay, which improve the specificity and sensitivity of oxiPTM detection [18].

Quantitative labeling strategies like OxICAT and iodoTMT offer site-specific quantification and enable differentiation between regulatory and stress-induced modifications [18]. These techniques have been successfully applied to characterize redox-sensitive proteins involved in diverse biological processes including photosynthesis, guard cell signaling, fruit ripening, and stress adaptation [18]. For example, tandem mass tag-based redox proteomics identified proteins responsive to flg22 in guard cells, revealing redox-dependent regulation of photosynthesis, lipid binding, and defense signaling [18]. In tomato, iodoTMT-based approaches identified 70 redox-sensitive peptides during fruit ripening, linking oxidation of specific enzymes to fruit softening [18].

The integration of redox proteomics with multi-omics approaches, including transcriptomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics, provides a holistic view of redox regulatory networks [18]. These integrative strategies help uncover cross-talk between different signaling pathways, allowing a systems-level understanding of redox-dependent metabolic reprogramming and stress responses [2] [18]. Resources like CPLM (Curated Protein Post-translational Modifications) support large-scale proteomic studies by cataloging diverse modifications, aiding the analysis of protein modification networks [18].

Computational Modeling and Artificial Intelligence

Recent breakthroughs in computational biology, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML) have significantly expanded the capabilities of redox research [18]. AI-driven predictive models and deep learning algorithms can now identify potential redox-sensitive sites, predict oxidative modifications, and uncover novel regulatory mechanisms with high precision [18]. Tools such as CysQuant, BiGRUD-SA, DLF-Sul, and iCarPS utilize machine learning frameworks to refine redox PTM predictions, enabling large-scale functional annotation of redox-modified proteins [18].

These computational approaches are transforming redox biology from a largely descriptive field into one that can predict and manipulate redox-dependent processes [18]. For example, computational tools have been developed to predict specific oxidative modifications including S-nitrosation, sulfenylation, S-glutathionylation, persulfidation, and disulfide bond formation [18]. The integration of experimental proteomics with AI-driven prediction platforms represents the future of redox systems biology, offering exciting possibilities for understanding complex redox networks and developing targeted interventions [18].

Specific Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Well-established experimental workflows for redox proteomics typically involve several key steps: sample collection under controlled redox conditions, protein extraction with preservation of redox states, enrichment of redox-modified peptides, mass spectrometry analysis (LC-MS/MS), and computational data analysis [18]. Specific protocols vary depending on the oxiPTM of interest. For detecting S-nitrosation, the Biotin-Switch Technique remains a standard method, involving blocking of free thiols, selective reduction of S-nitrosothiols, and labeling with biotin-HPDP for affinity purification [18].

For general cysteine oxidation monitoring, Iodoacetyl Tandem Mass Tag (iodoTMT) approaches enable multiplexed quantification of thiol oxidation states across multiple samples [18]. Resin-Assisted Capture (RAC) methods provide an alternative enrichment strategy that selectively captures thiol-containing peptides through covalent chromatography [18]. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations in terms of specificity, sensitivity, throughput, and compatibility with different biological systems.

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for redox proteomics analysis, integrating both experimental and computational components:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Investigating redox signaling mechanisms requires specialized reagents and tools designed to detect, quantify, and manipulate redox processes. The following table provides a comprehensive overview of essential research solutions for redox biology studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Redox Signaling Investigations

| Category/Reagent | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Redox Proteomics Enrichment | IodoTMT, ICAT, RAC, Biotin-Switch | Enrichment of redox-modified peptides | Enable quantification of oxidation states, specific for different oxiPTMs |

| ROS Detection Probes | H2DCFDA, MitoSOX, Amplex Red | Detection and quantification of specific ROS | Cell-permeable, target specific ROS (H₂O₂, O₂•⁻), compatible with live-cell imaging |

| Antioxidant Enzyme Assays | SOD, catalase, GPx activity kits | Measurement of antioxidant capacity | Colorimetric/fluorometric readouts, specific for each enzyme, high sensitivity |

| Thiol Status Assessment | DTNB, monobromobimane | Quantification of reduced/oxidized thiol ratios | Specific for thiol groups, enable GSH/GSSG ratio determination |

| NRF2 Pathway Modulators | Sulforaphane, bardoxolone | NRF2 activation studies | Induce endogenous antioxidant responses, research tools and therapeutic leads |

| NOX Inhibitors | GKT137831, VAS2870 | Specific inhibition of NADPH oxidases | Isoform-selective options, validate ROS sources, potential therapeutics |

| Computational Prediction Tools | CysQuant, BiGRUD-SA, DLF-Sul | Prediction of redox-sensitive sites | AI/ML-based, identify modification hotspots, guide experimental design |

| Redox Biosensors | roGFP, HyPer | Real-time monitoring of redox dynamics | Genetically encoded, subcellular targeting, rationetric quantification |

The selection of appropriate research tools depends on the specific research question, model system, and redox modification of interest. For comprehensive redox profiling, researchers often combine multiple approaches—for example, using computational predictions to identify candidate redox-sensitive cysteines, followed by experimental validation using redox proteomics and functional assays [18]. The increasing availability of genetically encoded redox biosensors like roGFP and HyPer enables real-time monitoring of redox dynamics in living cells with subcellular resolution [18]. These tools provide unprecedented spatial and temporal insights into redox signaling events as they occur in their native cellular context.

Emerging technologies continue to expand the redox biology toolkit. Tethered biosensors allow researchers to uncover intracellular redox heterogeneity by targeting specific subcellular compartments [21]. Advanced computational models integrate multi-omics data to predict redox-regulated networks and identify key regulatory nodes [18]. The combination of these experimental and computational approaches provides a powerful framework for deciphering the complex role of redox signaling in health and disease.

The field of redox biology has evolved from viewing reactive oxygen species solely as damaging molecules to recognizing their essential roles in physiological signaling and pathological processes. This paradigm shift has profound implications for therapeutic development, moving beyond nonspecific antioxidant approaches toward targeted strategies that respect the nuanced functions of redox signaling in specific cellular contexts [2] [17] [20]. Future progress will require increasingly sophisticated tools to investigate redox dynamics with greater spatial, temporal, and molecular precision.

Key challenges remain in translating our growing understanding of redox mechanisms into effective clinical interventions. These include developing precise assessment methods for redox homeostasis in patients, rationalizing delivery systems for redox-modulating compounds, and creating interventions that achieve context-specific modulation appropriate for different disease states [9]. The integration of computational approaches with experimental redox biology will be essential for predicting redox network behavior and identifying critical intervention points [18].

Emerging research areas promise to further expand our understanding of redox signaling in disease. These include investigating the role of redox regulation in interorgan crosstalk, sex differences in redox biology, the influence of lifestyle factors such as diet and exercise on redox physiology, and the development of multi-omics approaches to capture the complexity of redox networks [22]. As these advances unfold, redox-targeted therapies offer exciting potential for treating numerous diseases characterized by redox dysregulation, from cardiovascular and neurodegenerative conditions to cancer and metabolic disorders [2] [17] [16].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated approach required for advancing redox-targeted therapeutics from basic discovery to clinical application:

Redox signaling, a portmanteau of "reduction" and "oxidation," constitutes a fundamental chemical process involving electron transfer between molecules that is now recognized as a critical regulatory mechanism in cellular biology [2]. These reactions are integral to energy acquisition in organisms, primarily through oxidative respiration within cells [2]. During redox processes, cells generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide (O₂•⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), as well as reactive nitrogen species (RNS) such as nitric oxide (NO) and peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻) [23] [2]. While historically viewed solely as damaging molecules, it is now established that ROS and RNS function as important signaling mediators under physiological conditions [23] [2] [24].

The concept of the "Redox Code" outlines the organizing principles for biological redox signaling, emphasizing how NADH and NADPH systems regulate metabolism, how dynamic thiol switches control the redox proteome, and how cells activate and deactivate H₂O² production cycles in response to environmental changes [2]. This sophisticated regulatory system maintains redox homeostasis through a balance between oxidant generation and antioxidant defenses, including enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and small molecules such as glutathione and vitamin C [23] [2]. Disruption of this equilibrium contributes to various pathological conditions while intentional, mild oxidative stress can serve protective functions through hormetic mechanisms [23].

Molecular Mechanisms of Protein Redox Modifications

Classification of Protein Oxidative Modifications

Protein oxidative modifications are generally classified into two broad categories: irreversible oxidation and reversible oxidation [23] [25]. Irreversible oxidation typically leads to protein aggregation and degradation, significantly impairing protein function. This category includes the formation of protein carbonyls, nitrotyrosine, and sulfonic acids [23]. In contrast, reversible oxidation predominantly occurs on specific amino acid residues and often serves regulatory functions, operating as molecular "on and off" switches that control protein activity and redox signaling pathways in response to stress challenges [23] [25].

The most biologically significant reversible modifications occur on cysteine residues, which contain highly reactive thiol groups (-SH) that participate in various oxidative transformations [23] [2] [24]. When cysteine is in its ionized thiolate form (-S⁻), it becomes by far the most easily oxidized amino acid by hydroperoxides and the best nucleophile for other redox reactions [24]. The specific microenvironment of cysteine residues within proteins significantly influences their reactivity, with lowered pKa values and proximity to proton donors enhancing their susceptibility to redox modifications [24].

Major Types of Reversible Cysteine Modifications

Table 1: Major Types of Reversible Cysteine Redox Modifications

| Modification Type | Chemical Structure | Key Characteristics | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-Sulfenation | -SOH | Sulfenic acid formation; relatively unstable | Serves as intermediate for other modifications; regulates protein activity |

| S-Nitrosylation | -SNO | Addition of nitric oxide moiety | Transduces nitric oxide signaling; regulates protein function |

| S-Glutathionylation | -SSG | Mixed disulfide with glutathione | Protects from overoxidation; regulates metabolic enzymes |

| Disulfide Bond | -S-S- | Intramolecular or intermolecular bond | Stabilizes protein structure; regulates activity |

The specificity of redox signaling is achieved through several mechanisms. Unlike random oxidative damage, signaling-specific modifications target particular cysteine residues in specific microenvironments where the cysteine is ionized to the thiolate, and a proton can be donated to form a leaving group [24]. This precise chemical environment allows for selective modification without widespread non-specific oxidation [24]. Additionally, cellular compartmentalization and the proximity to ROS/RNS sources further enhance signaling specificity [24].

Diagram 1: Cysteine redox modification pathway. Reactive species modify cysteine thiols, leading to different reversible modifications that alter protein function.

Redox Regulation of Genomic Stability

Oxidative DNA Damage and Repair Systems

The genome is constantly assaulted by both endogenous and exogenous threats, with oxidative damage representing a significant challenge to DNA integrity [26]. On average, each mammalian cell experiences between 10,000-100,000 oxidative lesions to DNA daily, creating an enormous burden that must be efficiently repaired to maintain genomic stability [26]. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species can induce specific base modifications including 8-oxo-dG and 8-nitro-dG, as well as GC to TA transversions due to their high reactivity with nucleophilic sites on nucleobases [26]. These modifications, if unrepaired, can lead to mutations, chromosomal abnormalities, and ultimately contribute to disease pathogenesis including cancer, neurological disorders, and aging [26] [2].

Cells have evolved sophisticated DNA repair mechanisms to counter these threats, with different pathways addressing specific types of DNA damage [26] [2]:

- Base Excision Repair (BER): Primarily repairs oxidized bases and abasic sites using DNA glycosylases (e.g., OGG1 for 8-oxoguanine), AP endonuclease (APE1), DNA polymerase β, and DNA ligases [26].

- Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER): Handles bulkier DNA lesions including intra-strand crosslinks and protein-DNA adducts through complexes involving XPC, XPA, XPG, and ERCC proteins [26].

- Mismatch Repair (MMR): Corrects replication errors and oxidative mismatches using MutS and MutL complexes [26].

- Double-Strand Break Repair: Addresses the most severe DNA damage through either Homologous Recombination (HR) or Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathways [26] [2].

Redox Regulation of DNA Repair Proteins

Beyond causing direct DNA damage, redox signaling finely regulates the activity of DNA repair proteins through reversible modifications, creating a sophisticated feedback system that modulates the cellular response to genomic threats [26] [2]. This regulatory mechanism represents a crucial interface between oxidative stress responses and genome maintenance.

Table 2: Redox Regulation of Key DNA Repair Proteins

| DNA Repair Protein | Redox Modification | Functional Consequence | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATM Kinase | Cysteine oxidation | Activates kinase activity | Initiates DNA damage response; regulates cell cycle checkpoints |

| APE1 | Not specified | Modulates endonuclease activity | Affects BER efficiency; influences genomic stability |

| DNA Glycosylases | Not specified | Regulates base recognition and excision | Impacts removal of oxidized bases; affects mutation rates |

The activation of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein kinase exemplifies the sophisticated redox regulation of DNA repair mechanisms [2]. ATM activation is triggered by the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex upon detection of DNA double-strand breaks [2]. Oxidative stress can modify ATM through cysteine oxidation, phosphorylation, and acetylation, leading to ATM activation and subsequent recruitment of repair proteins such as p53 and CHK2 to regulate the cell cycle and DNA repair processes [2]. Dysfunction in these redox-regulated pathways can result in genomic instability and human diseases including Ataxia-Telangiectasia syndrome [2].

Diagram 2: Redox regulation of genomic stability. Oxidative stress causes DNA damage while simultaneously modifying repair proteins to activate genomic maintenance pathways.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Redox Modifications

Detection Methodologies for Reversible Cysteine Modifications

The study of reversible cysteine modifications requires specialized methodologies due to the labile nature of these modifications and the lack of inherent optical properties that would enable direct detection [23]. The biotin switch assay represents a widely employed general procedure for detecting various cysteine oxidation products [23]. This method involves three critical steps: (1) blocking of unmodified cysteine residues with alkylating reagents such as N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), (2) specific reduction of the modified cysteine species using selective reducing reagents, and (3) relabeling of the reduced cysteine residues with biotin-conjugated alkylating reagents for detection and purification [23].

The specificity of the biotin switch technique is achieved through the use of distinct reducing reagents for different modified species [23]. Ascorbic acid is employed for the reduction of S-nitrosylation, arsenite for the reduction of S-sulfenation, and glutaredoxin for the reduction of S-glutathionylation [23]. For detection and quantification of S-glutathionylation, the enzyme glutaredoxin is required in the presence of GSH [23]. It is important to note that nonspecific reducing reagents like DTT and 2-mercaptoethanol are unsuitable for distinguishing specific modifying species [23]. More recently, biotin-conjugated dimedone probes have been developed that react specifically with sulfenic acids (-SOH), enabling detection without the blocking and reducing steps [23].

Diagram 3: Biotin switch assay workflow. This method detects specific cysteine modifications through selective reduction and biotin labeling for detection or mass spectrometry analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Redox Biology Studies

| Research Reagent | Specific Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Alkylating agent that blocks free thiols | Prevents artificial oxidation during sample preparation; used in biotin switch assay |

| Biotin-conjugated NEM | Thiol-reactive biotin tag | Enables detection and affinity purification of previously oxidized cysteine residues |

| Ascorbic Acid | Selective reducing agent | Specifically reduces S-nitrosylated cysteine residues in biotin switch assays |

| Arsenite | Selective reducing agent | Specifically reduces S-sulfenated cysteine residues in biotin switch assays |

| Glutaredoxin | Enzyme catalyst | Reduces S-glutathionylated proteins in the presence of GSH |

| Biotin-Dimedone Probes | Specific sulfenic acid trap | Directly labels and detects protein sulfenic acids without reduction steps |

| Anti-biotin Antibodies | Detection reagent | Western blot detection of biotin-labeled previously oxidized proteins |

| Streptavidin Beads | Affinity matrix | Purification of biotin-labeled proteins for proteomic analysis |

Mass spectrometry has emerged as the most accurate and comprehensive method for studying protein modifications, enabling identification of modification sites, quantification of modification extent, and characterization of modified protein structures [25]. Advanced proteomic approaches now allow researchers to create detailed maps of the "redox proteome," identifying numerous proteins subject to regulatory redox modifications under various physiological and pathological conditions [2] [25]. These methodologies have been instrumental in expanding our understanding of the breadth and specificity of redox signaling networks.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The understanding of redox regulation mechanisms has opened promising avenues for therapeutic interventions across various human diseases [2]. Two primary mechanisms explain how redox imbalances contribute to pathology: (1) accumulation of ROS directly damages biomolecules including nucleic acids, membrane lipids, structural proteins, and enzymes, leading to cellular dysfunction or death; and (2) dysregulation in redox modifications causes aberrant redox signaling, where hydrogen peroxide and other reactive species serve as secondary messengers that disrupt normal cellular communication [2].

Diseases such as atherosclerosis, radiation-induced lung injury, and paraquat poisoning are directly attributed to or primarily caused by redox imbalances [2]. In contrast, conditions including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, hypertension, type II diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome are influenced indirectly by redox signaling through complex signal transduction pathways [2]. In these cases, redox signaling intersects with various cellular molecular events including DNA repair, epigenetic regulation, protein homeostasis, metabolic reprogramming, and modulation of the extracellular microenvironment [2].

Emerging therapeutic strategies focus on developing small molecule inhibitors that target specific cysteine residues in redox-sensitive proteins, several of which have demonstrated promising preclinical outcomes and are approaching clinical trials [2]. However, the complexity of redox signaling necessitates targeted approaches rather than broad-spectrum antioxidant interventions, which have shown limited efficacy and potential adverse effects in diseases with multifactorial etiologies [2]. Future research priorities include developing a deeper, context-specific understanding of redox signaling networks and identifying specific drug targets or critical modification sites for precise therapeutic interventions [2].

The field continues to evolve with ongoing research exploring the role of redox mechanisms in regulating epigenetic pathways, including miRNA, DNA methylation, and histone modifications [26] [2]. Additionally, investigations into how oxidative stress impacts gene regulation/activity and vice versa, how epigenetic processes and DNA repair influence cellular redox states, will further illuminate the complex interplay between redox biology and genome stability [26] [27]. These advances are expected to provide novel strategies for treating human diseases by targeting specific components of the redox regulatory system.

Advanced Techniques for Probing Redox Mechanisms

Redox reactions, fundamental processes involving electron transfer, are central to a vast array of scientific and industrial fields, from sustainable energy storage to cellular signaling. Understanding these mechanisms, however, is profoundly challenging because reactive intermediates and active states are often transient and exist only under specific operating conditions. In situ (under simulated reaction conditions) and operando (under operating conditions with simultaneous activity measurement) analytical techniques have emerged as powerful tools to overcome this challenge [28] [29]. They allow researchers to probe catalysts and biological systems in real-time, capturing dynamic changes that are invisible to conventional ex-situ methods.

This guide provides a comparative overview of key in situ and operando techniques, detailing their methodologies, applications, and limitations. By framing this within the broader thesis of validating redox reaction mechanisms, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to select the appropriate technique, implement robust experimental protocols, and interpret data to draw meaningful mechanistic conclusions.

Comparative Analysis of Key Techniques

A diverse suite of analytical techniques can be deployed for in situ and operando monitoring, each providing unique insights into different aspects of a redox process. The following table summarizes the primary techniques, their key applications in redox monitoring, and their inherent advantages and limitations.

Table 1: Comparison of Key In Situ and Operando Techniques for Redox Reaction Monitoring

| Technique | Primary Applications in Redox Monitoring | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS) | Probing local electronic and geometric structure of metal centers; identifying oxidation states and coordination chemistry [28] [29]. | Element-specific; can be applied to amorphous materials; provides direct information on oxidation state. | Requires synchrotron radiation source; complex data analysis; can average signals from bulk, not just surface. |

| Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR & Raman) | Identifying reaction intermediates and products adsorbed on surfaces; monitoring molecular bonding and degradation [28] [30]. | Highly sensitive to molecular structure and bonding; can identify specific intermediates. | Signals can be weak; potential for laser-induced damage (Raman); interpretation of surface species can be ambiguous. |

| Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (EC-MS) | Quantitative detection of volatile reactants, intermediates, and products; correlating electrochemical current with product formation [28]. | Highly sensitive and selective; enables quantitative tracking of gas evolution reactions. | Limited to volatile species; requires careful reactor design to minimize response time [28]. |

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Detecting and quantifying paramagnetic species (e.g., radicals, certain metal ions) generated during redox processes [30]. | Uniquely sensitive to paramagnetic centers; can provide insights into radical mechanisms. | Only applicable to paramagnetic systems; can be challenging to perform under operando electrochemical conditions. |

Experimental Protocols for Technique Validation

Robust experimental design is critical for generating reliable and interpretable in situ and operando data. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in recent literature, highlighting best practices and essential controls.

Protocol for Operando XAS in Electrocatalysis

Objective: To determine the change in oxidation state and local coordination environment of a metal oxide catalyst (e.g., IrO₂) during the Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER) [29].

- Cell Design: Utilize an electrochemical flow cell with X-ray transparent windows (e.g., Kapton film). The working electrode is typically a thin catalyst film coated on a carbon paper or glassy carbon substrate [28].

- Data Collection:

- Setup: Align the cell at a synchrotron beamline. Measure the X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of the catalyst at a constant applied potential under inert conditions to establish a baseline.

- Operando Measurement: Flow electrolyte through the cell while applying a series of controlled anodic potentials (e.g., from open-circuit voltage to OER potentials). Collect XAS spectra at each potential step while simultaneously recording the electrochemical current.

- Reference Standards: Collect XAS data from reference compounds with known oxidation states (e.g., Ir, IrO₂) for linear combination analysis.

- Data Analysis:

- Process the XANES region to track the energy shift of the absorption edge, which correlates with the average oxidation state of the metal.

- Fit the EXAFS region to extract structural parameters like coordination numbers and bond distances, revealing changes in the catalyst's structure under potential control.

- Key Controls: Perform an identical experiment without the catalyst to subtract any signal from the electrode substrate or electrolyte. Validate findings with complementary techniques, such as XRD, to rule out crystallization or phase segregation [29].

Protocol for In Situ Electrochemical Raman Spectroscopy

Objective: To identify adsorbed oxygenated intermediates (e.g., *OOH) on a NiFe-based OER catalyst in an alkaline medium [29].

- Cell Design: Use a three-electrode electrochemical cell with an optically flat window. The working electrode is a catalyst film on a reflective substrate (e.g., Au). A laser source is focused through the window onto the electrode surface.

- Data Collection:

- Setup: Acquire a Raman spectrum of the catalyst at open circuit potential.

- Operando Measurement: Apply a constant anodic potential to initiate the OER. Collect Raman spectra continuously or at fixed time intervals. Integration times should be optimized to obtain a good signal-to-noise ratio without causing laser-induced heating or degradation.

- Isotope Labeling: To confirm the origin of vibrational modes, repeat the experiment using heavy oxygen isotope (¹⁸O)-labeled water. A characteristic shift in the Raman bands confirms the signal originates from oxygen-containing surface species [29].

- Data Analysis:

- Subtract the spectrum collected at open circuit as the background.

- Identify new peaks that emerge under potential and assign them to specific molecular vibrations (e.g., M-O, O-O) by comparison to literature and theoretical calculations.

- Key Controls: Test the bare substrate under identical conditions to account for its spectral features. Use isotope labeling (H₂¹⁸O) to confirm that Raman bands assigned to O-O stretching shift as predicted, providing definitive evidence for reaction intermediates [28].

Protocol for Disulfide Trapping in Cellular Redox Relays

Objective: To identify protein partners that interact via disulfide bond exchange in a cellular redox signaling pathway [31].

- Cell Lysis and Trapping: Lyase cells under non-reducing conditions (i.e., without β-mercaptoethanol or DTT) to preserve native disulfide bonds. Include alkylating agents like N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to block free thiols and prevent post-lysis disulfide scrambling.

- Thiol-Dependent Cross-Linking: Treat the lysate or intact cells with a thiol-cleavable cross-linker such as dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) (DSP). This cross-links proteins in close proximity.

- Affinity Purification: Immunoprecipitate the protein of interest using a specific antibody.

- Reduction and Elution: Elute bound protein complexes from the beads by treating with a reducing agent (e.g., DTT), which cleaves both the endogenous disulfide bonds and the cross-linker.

- Analysis: Analyze the eluted proteins by SDS-PAGE (under reducing conditions) and mass spectrometry to identify the specific protein partners that were engaged in a disulfide bond with the target [31].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Redox Pathways

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the logical flow of a generalized operando study and a key biological redox signaling pathway investigated with these techniques.

Operando Analysis Workflow

Cellular Redox Signaling Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful in situ and operando studies rely on specialized materials and reagents tailored to maintain controlled environments and enable specific detection.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Reaction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| X-ray Transparent Windows (e.g., Kapton film) | Allows penetration of high-energy X-rays into the operando electrochemical cell while sealing the reactor [28]. |

| Isotope-Labeled Reactants (e.g., H₂¹⁸O, ¹³CO₂) | Serves as tracers to unequivocally confirm the molecular origin of reaction intermediates and products using techniques like Raman or MS [28] [29]. |

| Thiol-Alkylating Agents (e.g., N-Ethylmaleimide, NEM) | Blocks free cysteine thiols in biological redox studies to "freeze" transient disulfide bonds and prevent post-lysis scrambling during analysis [31]. |

| Thiol-Cleavable Cross-linkers (e.g., DTSP, DSP) | Chemically cross-links protein partners that are in close proximity, allowing for the identification of disulfide-based protein complexes after cleavage [31]. |

| Ion-Exchange Membranes (e.g., Nafion) | Serves as a separator in electrochemical flow cells (e.g., for RFBs or DEMS) to facilitate ion transport while preventing short-circuiting and crossover of reactants [30]. |

| Pervaporation Membranes (in DEMS) | A key component in Differential Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry cells, allowing selective transport of volatile products from the electrolyte to the mass spectrometer for real-time analysis [28]. |

The advent of in situ and operando analysis has fundamentally transformed our ability to deconvolute complex redox mechanisms across chemistry, materials science, and biology. As this guide illustrates, no single technique provides a complete picture; rather, a multimodal approach is essential. The future of this field lies in the continued innovation of reactor designs that better mimic real-world operating conditions [28], the development of new methodologies to probe faster and more transient events, and the strategic integration of data with theoretical modeling. By adhering to rigorous experimental protocols and leveraging the complementary strengths of various techniques, researchers can continue to validate and refine our understanding of redox processes, accelerating the development of better catalysts, energy storage devices, and therapeutic strategies.

The validation of redox reaction mechanisms is a cornerstone of research in fields ranging from drug development to energy storage and materials science. Understanding these complex processes requires analytical techniques capable of probing molecular states and electronic structures with high specificity and sensitivity. Among the most powerful tools for these investigations are Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Each technique offers unique capabilities for identifying chemical states, tracking reaction pathways, and characterizing paramagnetic intermediates that often play crucial roles in redox processes.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three spectroscopic methods, focusing on their operational principles, experimental requirements, and performance characteristics for state identification in the context of redox mechanism validation. By presenting structured experimental data and protocols, we aim to equip researchers with the information necessary to select the most appropriate technique for their specific investigative needs.

Technical Comparison of Spectroscopic Methods

The following table provides a systematic comparison of the three spectroscopic techniques across key technical parameters:

Table 1: Technical comparison of NIR, Raman, and EPR spectroscopy

| Parameter | NIR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy | EPR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Overtone and combination vibrations of C-H, O-H, N-H bonds | Inelastic scattering due to molecular vibrations | Resonance absorption by unpaired electrons in magnetic field |

| Spectral Range | 750-2500 nm (4000-12800 cm⁻¹) [32] [33] | Typically 500-2000 cm⁻¹ shift from laser line | Typically 9-10 GHz (X-band) at 0.3-0.4 T |

| Information Obtained | Molecular overtone/combination bands, hydrogen bonding, hydration states | Molecular fingerprint, chemical structure, crystallinity, stress | Oxidation state, coordination geometry, identity of paramagnetic centers |

| Sample Form | Liquids, solids, powders, tablets | Solids, liquids, powders, thin films | Solids, powders, frozen solutions |

| Detection Limit | ~0.1% for major components [32] | Single molecule with SERS [34]; ~μM for常规 Raman | ~10¹² spins (nanomolar for favorable systems) [35] |

| Key Applications | Quality control, raw material ID, moisture analysis, process monitoring | Polymorph identification, contaminant detection, strain mapping | Reaction intermediate tracking, defect characterization, radical detection |

| Quantitative Capability | Excellent with chemometrics [36] [33] | Good with careful calibration | Good for spin concentration, challenging for complex mixtures |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy

Protocol for Quantitative Analysis of Pharmaceutical Compounds [32] [33]:

Instrumentation: Use an FT-NIR spectrometer equipped with a diffuse reflectance probe or integrating sphere. The spectrometer should cover the range of 750-1500 nm or 4000-10000 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 8-16 cm⁻¹.

Sample Preparation:

- For tablets: Analyze intact tablets without crushing to maintain structural information.

- For powders: Place in a standard sample cup and ensure consistent packing density.

- For liquids: Use transmission cells with fixed pathlength (typically 1-10 mm).

Spectral Acquisition:

- Acquire 32-64 scans per spectrum to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Collect background reference spectra regularly (every 30-60 minutes).

- Maintain consistent temperature during measurement.

-

- Apply Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) to remove scattering effects.

- Use Savitzky-Golay derivatives (1st or 2nd derivative) to enhance spectral features and remove baseline offsets.

- Employ vector normalization when comparing relative changes.

Chemometric Modeling [33]:

- Develop partial least squares (PLS) or convolutional neural network (CNN) models using reference values from primary methods (e.g., HPLC).

- Validate models using independent test sets not included in model calibration.

- Monitor model performance with statistical parameters (R², RMSEP, bias).

Raman Spectroscopy

Protocol for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) [34]:

Substrate Selection and Characterization:

- Choose commercial SERS substrates (gold or silver nanoparticles on silicon or glass).

- Characterize substrates using SEM to confirm nanostructure morphology and distribution.

- Select substrates with high enhancement factors (typically 10⁶-10⁸ for optimal sensitivity).

Sample Preparation:

- For analyte solutions: Prepare concentration series (e.g., 10⁻² to 10⁻¹² M).

- Immerse substrates in analyte solutions for 1 hour to allow adsorption.

- Remove substrates and dry for 15 minutes to concentrate analyte at hot spots.

Instrument Parameters:

- Use a 532 nm or 785 nm laser excitation source with power 1-10 mW at sample.

- Employ a microscope with 20× or 50× objective for focused excitation.

- Set grating to 600-1800 grooves/mm for optimal resolution and range.

- Use exposure times of 1-10 seconds with 1-10 accumulations.

Spectral Collection:

- Calibrate spectrometer daily using silicon peak (520 cm⁻¹).

- Collect spectra from 15-20 random points on substrate to account for heterogeneity.

- Include control spectra from clean substrates for background subtraction.

Data Processing:

- Remove fluorescence background using polynomial fitting or spline correction.

- Normalize spectra to internal standard or most intense peak.

- For machine learning applications, use vector normalization before classification.

Table 2: SERS enhancement factors for different substrate morphologies [34]

| Substrate Type | Nanoparticle Material | Average Particle Size (nm) | Enhancement Factor | Optimal Analyte |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | Gold and silver on glass | 100-300 | 10⁷-10⁸ | Rhodamine B, dyes |

| Type B | Gold on silicon | ~97 | 10⁶-10⁷ | Pesticides, explosives |

| Type C | Silver on silicon | ~18 | 10⁵-10⁶ | Small molecules |

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy

Protocol for Davies ENDOR Spectroscopy [37] [35]:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare 1-5 mM solutions of paramagnetic species in appropriate solvent.

- For frozen solutions, use solvent mixtures that form clear glass (e.g., glycerol/water, deuterated solvents).

- Transfer 40-50 μL to quartz EPR tube (3-4 mm outer diameter).

- Flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen to maintain homogeneous distribution.

Instrument Setup:

- Set microwave frequency to X-band (∼9-10 GHz).

- Adjust magnetic field to maximum of echo-detected EPR spectrum.

- Maintain temperature at 10-50 K using helium cryostat.

- Set shot repetition time based on electron spin relaxation (typically 1-100 ms).

Pulse Sequence Parameters (Davies ENDOR):

- Selective microwave π pulse: 100-200 ns.

- Observer π/2 and π pulses: 10-20 ns.

- RF pulse length: 10-50 μs with quarter-sine shaping at edges.

- τ value (between pulses): 300-500 ns.

- RF power: 100-500 W.

Data Acquisition:

- Use stochastic acquisition of RF frequencies to avoid nuclear saturation.

- Employ four-step phase cycling to eliminate artifacts.

- Acquire 25-100 scans per spectrum depending on signal-to-noise.

- Set RF frequency range based on nuclear Larmor frequencies (e.g., 1-50 MHz for metals).

Advanced Implementation (Chirped Pulses):

- Replace single-frequency RF pulses with chirped pulses for broad excitation.

- Set chirp bandwidth to match ENDOR linewidth (typically 5-15 MHz).

- Use lower RF powers (100 W vs. 500 W) to reduce amplifier overtones.

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Sensitivity and Specificity in Practical Applications

Table 3: Performance comparison for pharmaceutical analysis [32]

| Performance Metric | NIR Spectroscopy | HPLC (Reference) | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (All Drugs) | 11% | 100% (by definition) | Not reported |

| Specificity (All Drugs) | 74% | 100% (by definition) | Not reported |

| Sensitivity (Analgesics) | 37% | 100% | Not reported |

| Specificity (Analgesics) | 47% | 100% | Not reported |

| Analysis Time | ~20 seconds | Hours including preparation | Minutes to hours |