Strategies for Controlling Capacitive Currents in Redox Experiments: A Guide for Electrochemical Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing capacitive currents in redox-based electrochemical experiments.

Strategies for Controlling Capacitive Currents in Redox Experiments: A Guide for Electrochemical Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing capacitive currents in redox-based electrochemical experiments. Capacitive currents, which arise from non-Faradaic charging processes at electrode-electrolyte interfaces, can significantly obscure the accurate measurement of Faradaic signals from redox-active analytes—a critical challenge in developing biosensors, studying drug metabolism, and characterizing biomolecular interactions. We explore the fundamental origins of capacitive currents in various electrochemical systems, from traditional aqueous buffers to advanced redox flow cells. The content details practical methodologies for measurement and suppression using techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and pulsed voltammetry. Furthermore, we present systematic troubleshooting approaches for optimizing signal-to-noise ratios and validate these strategies through comparative analysis of electrochemical systems, enabling more reliable data interpretation in biomedical and clinical research applications.

Understanding Capacitive Currents: Fundamentals and Challenges in Electrochemical Systems

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts for Troubleshooting

What is the fundamental difference between faradaic and capacitive current?

In electrochemical systems, the total current measured at a working electrode is the sum of faradaic and capacitive (non-faradaic) currents, which originate from two distinct charge transfer mechanisms at the electrode-electrolyte interface [1] [2].

- Faradaic Current: This current arises from electron transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface, leading to the reduction or oxidation (redox reactions) of electroactive species. It is faradaic current that provides information about the kinetics, thermodynamics, and mechanism of the electrochemical process under study [1]. For example, in a vanadium flow battery, the current associated with the conversion between V²⁺ and V³⁺ is faradaic [3].

- Capacitive Current (Non-Faradaic): This current originates from the redistribution of charged species (ions) in the electrolyte near the electrode surface. No electrons are transferred across the interface, and no chemical reactions occur. This process forms the electrical double layer, which behaves like a capacitor (Cdl), and the current is associated with the charging and discharging of this capacitor. It is often treated as a "background current" [1] [2].

Why is distinguishing between these currents critical in my redox experiments?

Accurately distinguishing between these currents is essential for correct data interpretation, as it directly impacts the analysis of your redox system's performance and health.

- Quantifying Redox Activity: Only the faradaic component corresponds to your desired redox reaction. Failing to account for capacitive contributions can lead to overestimating the charge capacity, efficiency, or apparent rate of your reaction [1].

- Assessing System Health and Kinetics: A significant and increasing capacitive current can sometimes indicate unwanted surface processes, such as the formation of oxide layers or the breakdown of the electrolyte, which can obscure the fundamental redox signal you intend to measure [2].

A common problem is an unexpectedly high or unstable background current. What could be the cause?

A high or fluctuating background current often points to issues related to the capacitive (non-faradaic) component. Common culprits include:

- Electrode Surface Contamination: Adsorption of impurities from the electrolyte or atmosphere can alter the double-layer structure and its capacitance.

- Unstable Electrical Double Layer: Changes in electrolyte composition, temperature, or flow rate (in flow systems) can prevent a stable double layer from forming, leading to current drift [3].

- Unwanted Faradaic Processes: The "background" may include minor faradaic reactions from trace impurities or electrode corrosion (e.g.,

Pt + 4Cl⁻ → [PtCl₄]²⁻ + 2e⁻) [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Symptom: Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Cyclic Voltammetry

- Problem: The faradaic peaks from your redox species are obscured by a large capacitive background.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Electrolyte resistance. Solution: Ensure your supporting electrolyte concentration is sufficiently high (typically 10-100 times greater than the analyte concentration) to minimize ohmic drop.

- Cause: Slow scan rate for a system with low analyte concentration. Solution: The capacitive current is proportional to scan rate (v), while the faradaic current is proportional to v¹/². Try increasing the scan rate to enhance the faradaic-to-capacitive current ratio [1].

- Cause: Dirty or poorly prepared electrode surface. Solution: Re-polish and clean the electrode according to established protocols for your electrode material.

Symptom: Inconsistent Charge/Discharge Curves in Battery Tests

- Problem: The voltage profiles during galvanostatic cycling are unstable or the measured capacity drifts significantly.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Unstable faradaic reactions due to side reactions. Solution: Review the electrochemical stability window of your electrolyte to ensure it is compatible with your operating voltage [4].

- Cause: Evolution of the electrode/electrolyte interface. Solution: In systems like lithium-metal or solid-state batteries, the formation and evolution of interphases (SEI) can create a significant and variable capacitive-like current that consumes charge without contributing to usable capacity [4]. Characterization techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) can help monitor this interface evolution.

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing the Electrode-Electrolyte Interface

This protocol outlines a methodology using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to characterize the interface, inspired by studies on modified electrodes and battery interfaces [5] [4].

1. Objective To separate and quantify the faradaic and capacitive current contributions at an electrode-electrolyte interface and evaluate the stability of the interface over time.

2. Materials and Reagents Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, H₂SO₄) | Provides ionic conductivity; defines the electrical double-layer structure without participating in faradaic reactions. |

| Electrode Polishing Kit (e.g., alumina slurry) | Ensures a reproducible, clean, and well-defined electrode surface before each experiment. |

| Redox Probe (e.g., 1-5 mM K₃Fe(CN)₆) | A well-understood, reversible redox couple used to benchmark faradaic performance and cell health. |

| Deaerating Agent (e.g., N₂ or Ar gas) | Removes dissolved oxygen from the electrolyte to prevent unwanted faradaic currents from O₂ reduction. |

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Electrode Preparation

- Polish the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon) sequentially with finer grades of alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a micro-cloth.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water after each polish and sonicate for 1-2 minutes to remove embedded particles.

Step 2: Baseline Characterization in Blank Electrolyte

- Place the polished electrode and counter/reference electrodes into a cell containing only the supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl).

- Decorate the solution with inert gas (N₂/Ar) for 10-15 minutes.

- Record a Cyclic Voltammogram (CV) at your chosen scan rate(s) (e.g., 50 mV/s) over a potential window where no faradaic reactions occur. This CV is your capacitive background current.

- Optionally, perform EIS at the open-circuit potential to determine the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) and solution resistance.

Step 3: Measurement with Redox Active Species

- Add a known concentration of your redox probe (e.g., K₃Fe(CN)₆) to the cell.

- Record CVs at multiple scan rates (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 100, 200 mV/s).

Step 4: Data Analysis

- For a specific potential, plot the peak current (ip) from the CVs against the square root of the scan rate (v¹/²). A linear relationship confirms a diffusion-controlled (faradaic) process.

- The capacitive current at any potential can be estimated from the baseline measurement in the blank electrolyte. The faradaic current is the total measured current minus this capacitive contribution.

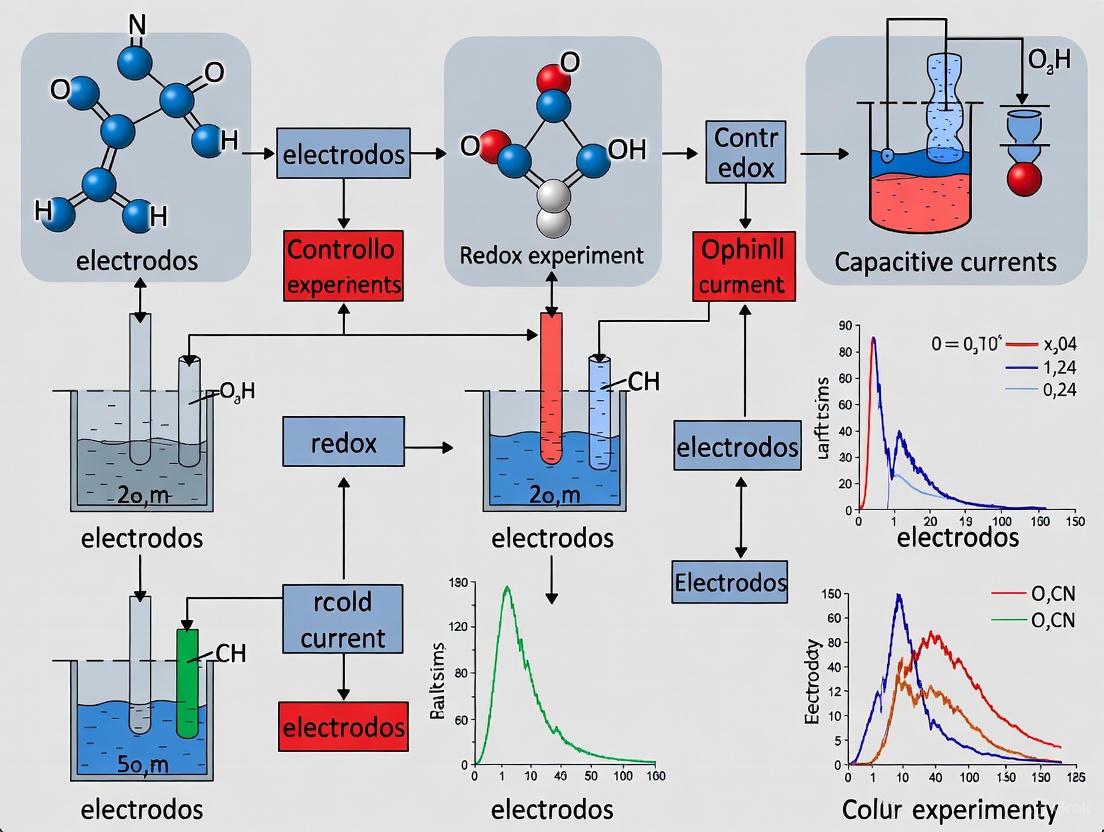

The workflow and core relationships for this analytical process are summarized in the following diagram:

Technical Reference Tables

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Faradaic and Capacitive Currents

| Parameter | Faradaic Current | Capacitive Current |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Electron transfer (Redox reactions) | Charge redistribution in Electrical Double Layer [1] [2] |

| Electron Transfer | Yes [1] | No [1] [2] |

| Dependence on Scan Rate (v) | Proportional to v¹/² [1] | Proportional to v [1] |

| Reversibility | Chemically reversible or irreversible | Highly electrically reversible [2] |

| Primary Information | Reaction kinetics, thermodynamics, mechanism | Electrode surface area, double-layer structure |

Table 2: Common Electrode Reactions and Their Type

| Reaction Example | Process Type | Current Type |

|---|---|---|

VO²⁺ + H₂O → VO₂⁺ + 2H⁺ + e⁻ (Oxidation) [3] |

Faradaic | Faradaic |

2H₂O + 2e⁻ → H₂↑ + 2OH⁻ (Reduction) [2] |

Faradaic | Faradaic |

PtO + 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ ⇌ Pt + H₂O [2] |

Faradaic (Reversible) | Faradaic |

| Cation attraction / Anion repulsion at a negative electrode [2] | Non-Faradaic | Capacitive |

| Charging of the double-layer capacitor (Cdl) [2] | Non-Faradaic | Capacitive |

The fundamental charge transfer mechanisms at the electrode-electrolyte interface, which are the source of the two current types, can be visualized as follows:

FAQs: Understanding the Electrical Double Layer (EDL)

Q1: What is an Electrical Double Layer and why does it cause a capacitive background in my experiments?

An Electrical Double Layer (EDL) is a structure that forms at the interface between an electronic conductor (e.g., an electrode) and an ionic conductor (e.g., an electrolyte) [6]. When these two phases come into contact, the charged electrode surface causes ions in the electrolyte to rearrange [7]. This creates two parallel layers of charge: the first is the charged electrode surface itself, and the second is a layer of ions from the solution that are attracted to the surface charge via the Coulomb force, electrically screening it [6]. This entire arrangement, comprising the electrode charge and the balancing ionic charge in the solution, behaves like a molecular capacitor, storing charge electrostatically [8]. This capacitor-like behavior is the direct source of the non-Faradaic capacitive background or charging current you observe in your experiments, which occurs independently of any redox reactions [9].

Q2: What are the key structural parts of the EDL I need to know about?

Modern EDL models typically describe three key parts, as visualized in the diagram below [6] [8]:

EDL Structure Overview

- Stern (or Compact) Layer: The layer of ions (counterions) that are directly attached to the electrode surface due to strong chemical interactions or electrostatic forces, and are immobile [8] [7]. It is divided by the Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP), which passes through the centers of specifically adsorbed ions that may have lost their solvation shell, and the Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP), which passes through the centers of solvated ions at their distance of closest approach to the electrode [6].

- Diffuse Layer: A layer of free ions outside the OHP that are loosely associated with the electrode [6]. These ions are affected by both electric attraction from the electrode and thermal motion, creating a cloud where the concentration of counterions gradually decreases until it matches the bulk solution [6] [7]. The electric potential at the boundary of the moving fluid, known as the slipping plane, is called the Zeta Potential, a critical parameter for colloidal interactions [6] [8].

Q3: How does electrolyte concentration affect the capacitive background?

Electrolyte concentration has a profound effect on the EDL and thus the capacitive background. Higher ion concentrations lead to more effective screening of the electrode's electric field [7]. This means the potential from the electrode surface decays to zero more quickly in the solution. The characteristic distance over which this potential decays is called the Debye length [7]. A higher electrolyte concentration results in a shorter Debye length and a thinner diffuse layer. This changes the differential capacitance of the interface and can lead to a larger observed capacitive background current, especially in techniques like cyclic voltammetry where the interface is charged and discharged rapidly [6].

Q4: I've heard of "pseudocapacitance." How is it different from the double-layer capacitance?

This is a crucial distinction for interpreting your data.

- Double-Layer Capacitance: Energy is stored purely electrostatically. There is no transfer of electrons across the electrode interface (non-Faradaic). The process is highly reversible and fast [9].

- Pseudocapacitance: Energy is stored through superficial, reversible Faradaic redox reactions (electron transfer) at the electrode surface [6] [9]. While the current response in a cyclic voltammogram can appear capacitor-like, it involves a chemical reaction. Examples include systems with ruthenium oxide (RuO₂) or manganese oxide (MnO₂) electrodes [9].

Q5: My capacitive background is unexpectedly high. What are the common causes?

An unexpectedly high capacitive background can stem from several factors:

- High Electrode Surface Area: The double-layer capacitance is proportional to the electrochemically active surface area [9]. Using porous electrodes (like carbon felt) or nanostructured surfaces dramatically increases the area, leading to a larger total capacitance.

- Electrolyte Composition: As per Q3, high ionic strength electrolytes can contribute to a higher capacitance. The specific identity of the ions can also lead to "specific adsorption," where ions penetrate the Stern layer, potentially increasing capacitance [6].

- Surface Functionalization: The presence of functional groups on the electrode surface (e.g., oxygenated groups on carbon) can introduce pseudocapacitive effects, adding a Faradaic component to the background current [9].

- Slow Redox Kinetics: If the redox reaction you are studying is slow, the Faradaic current may be small, making the non-Faradaic capacitive background appear disproportionately large in comparison.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Overwhelming Capacitive Background Obscuring Faradaic Peaks

| Step | Action | Principle & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Electrode Surface Area | A porous or rough electrode has a much larger true surface area than its geometric area, leading to higher capacitance [9]. Switch to an electrode with a smaller, well-defined surface area (e.g., glassy carbon instead of porous carbon felt). |

| 2 | Optimize Electrolyte | A highly concentrated electrolyte screens the surface charge more effectively, leading to a different capacitance profile [7]. Dilute your electrolyte if possible, but ensure it remains conductive enough to avoid large iR drop. |

| 3 | Adjust Potential Scan Rate | The capacitive current is proportional to the scan rate (iC ∝ ν), while the current for a diffusion-controlled Faradaic peak is proportional to the square root of the scan rate (iP ∝ ν^(1/2)) [9]. Lower your scan rate to suppress the capacitive current relative to the Faradaic current. |

| 4 | Employ Background Subtraction | The capacitive background is a characteristic of the electrode/electrolyte interface. Record a cyclic voltammogram in a potential window without Faradaic peaks (e.g., in supporting electrolyte alone) and subtract it from your data. |

Issue 2: Inconsistent Capacitance Measurements Between Techniques

When measuring the capacitance of a material or interface, it is common to get different values from Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Galvanostatic Charge/Discharge (GCD), and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). This is often related to the different timescales and penetration depths of these methods, especially in porous materials [9].

Troubleshooting Inconsistent Capacitance

| Technique | Common Pitfall | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Using an inappropriate potential window or scan rate. | Measure capacitance at multiple scan rates. Use the formula C = i / ν (from CV) and report the value from the lowest practical scan rate where the interface is fully charged [9]. |

| Galvanostatic Charge/Discharge (GCD) | Ignoring the voltage drop (IR drop) at the beginning of discharge. | Calculate capacitance using the discharge curve only, excluding the IR drop: C = I / (dV/dt) [9]. |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Incorrectly fitting the impedance data or choosing a non-ideal frequency. | Extract the complex capacitance. The capacitance value at the lowest frequency (e.g., 1-10 mHz) is often taken as the full, equilibrium capacitance, as it allows the electrolyte to penetrate the deepest pores [9]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in EDL & Capacitive Studies |

|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, NaClO₄, H₂SO₄) | Provides a high concentration of inert ions to ensure solution conductivity. Its primary function is to minimize the solution resistance (iR drop) and define the Debye length, which controls the thickness of the diffuse double layer [7]. The choice of anion/cation can affect specific adsorption. |

| Inert Working Electrodes (e.g., Glassy Carbon, Au, Pt) | Provide a well-defined, reproducible, and electrochemically inert surface in a specific potential window for fundamental studies of the EDL without interference from redox processes or corrosion. |

| Porous Carbon Electrodes (e.g., Activated Carbon, Carbon Felt) | Provide an extremely high surface area (up to 1000-2000 m²/g) to maximize the total double-layer capacitance for energy storage applications (supercapacitors) [9]. |

| Solvent (e.g., Water, Acetonitrile, DMSO) | The solvent's permittivity (ε) is a key factor in the capacitance, as seen in the Helmholtz model (C ∝ ε) [8]. It also determines the electrochemical window and the solubility of electrolytes. |

| Redox-Active Probes (e.g., Ferrocene, K₃Fe(CN)₆) | Used as internal or external standards to differentiate between capacitive currents (linear with scan rate) and diffusion-controlled Faradaic currents (square root of scan rate) during method validation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Double-Layer Capacitance via Cyclic Voltammetry

This protocol allows you to measure the capacitance of your electrode-electrolyte interface, a critical parameter for understanding your system's capacitive background.

Methodology:

- Setup: Use a standard three-electrode configuration with your material as the working electrode.

- Potential Window Selection: First, run a CV at a slow scan rate (e.g., 10 mV/s) over a wide potential range to identify a region where no Faradaic reactions occur. This is your "non-Faradaic" or "capacitive" window.

- Multi-Scan Rate CV: Record CVs within this non-Faradaic window at a series of scan rates (e.g., 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 mV/s).

- Data Analysis:

- At a fixed potential within the window (typically near the middle), extract the current (i) from each CV.

- Plot the current (i) versus the scan rate (ν).

- The capacitance (C) is calculated from the slope of the linear fit of this plot, based on the equation for a capacitor: i = C * ν. The slope is equal to the capacitance C [9].

Protocol 2: Differentiating Capacitive vs. Diffusion-Controlled Currents

This protocol helps deconvolute the total current into its capacitive and Faradaic components, which is essential for analyzing redox experiments.

Methodology:

- Setup: As in Protocol 1, with your redox-active species in the electrolyte.

- Multi-Scan Rate CV: Record CVs over a potential window that includes your Faradaic peaks, using a series of scan rates (e.g., from 5 mV/s to 500 mV/s).

- Power-Law Analysis:

- For a given peak, plot the log of the peak current (log(i_p)) versus the log of the scan rate (log(ν)).

- Fit the data to the power-law relationship: i = a * ν^b.

- Interpret the value of the exponent b:

- b = 0.5 indicates a current that is diffusion-controlled (ideal for many redox couples).

- b = 1.0 indicates a current that is surface-controlled or capacitive (non-Faradaic) [9].

- A value between 0.5 and 1.0 suggests a mix of diffusion-controlled and capacitive processes.

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Voltammetric Measurements

Problem: The faradaic (redox) signal from a drug compound is obscured by a large, non-faradaic capacitive background current, making it difficult to identify oxidation or reduction peaks.

Why This Happens: The capacitive current arises from the charging of the electrical double-layer at the electrode-solution interface, akin to a capacitor. This background is always present and can overwhelm the faradaic current from the redox reaction of your analyte, especially at low concentrations [10].

Solutions:

- Modify the Electrode Surface: Modify a standard glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with a self-assembled monolayer of alkanethiols on a nanoporous gold (NPG) surface. This modification passivates the electrode, significantly reducing the capacitive background and minimizing signal interferences [10].

- Employ Advanced Voltammetric Techniques: Switch from basic Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) to pulsed techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV). DPV applies potential pulses in a way that measures the current just before the pulse (which is largely capacitive) and subtracts it from the peak current (which is faradaic), effectively suppressing the capacitive background [11].

- Optimize Experimental Parameters:

- Use a Supporting Electrolyte: Ensure a high concentration (e.g., 0.1-1.0 M) of an inert electrolyte (e.g., KCl, phosphate buffer) is present. This decreases the solution resistance and compresses the electrical double layer, reducing its capacitance.

- Clean the Electrode Meticulously: Follow a strict electrode cleaning and polishing protocol before each experiment. Any adsorbed contaminants can dramatically increase capacitive current.

Inconsistent Results in Drug-DNA Binding Studies

Problem: The measured binding constant for a drug interacting with DNA varies significantly between experiment repetitions.

Why This Happens: Inconsistencies often stem from unstable capacitive backgrounds and fluctuating faradaic signals. This can be caused by electrode fouling, slight variations in DNA concentration, or instability of the drug-DNA adduct. The binding event itself can alter the diffusion coefficient of the drug and its redox properties, which are measured against the capacitive background [11].

Solutions:

- Characterize Electrode Surface Consistently: Use a standard redox probe like potassium ferricyanide to check the state of your electrode before and after each drug-DNA experiment. A stable and reproducible peak for the probe ensures your electrode surface is consistent.

- Implement a Rigorous Experimental Workflow: Follow a standardized protocol for adding DNA to the drug solution. Always run a baseline measurement of the drug alone and the DNA alone to establish their individual electrochemical signatures.

- Verify Binding Mode with Controls: If your drug is suspected to be an intercalator, use a known intercalator (e.g., amsacrine) as a positive control. Similarly, use a groove binder as a control if that is the expected mode. This helps confirm that the observed signal changes are due to the specific binding interaction [11].

Unstable Baseline in Capacitive Sensing of Biomolecules

Problem: When using a capacitive biomedical sensor (e.g., for electromyography), the baseline drifts or is noisy, making it difficult to resolve the bio-signal.

Why This Happens: The capacitance at the skin-electrode interface is highly sensitive to factors like pressure, movement, and perspiration. These factors change the effective distance and permittivity of the insulating layer, directly impacting the capacitive current [12].

Solutions:

- Improve Insulator Stability: Select a stable, breathable, and hypoallergenic insulator like a micropore medical bandage. This material provides a consistent capacitance and reduces discomfort and perspiration during long-term measurements [12].

- Implement Signal Filtering: Integrate a 50 Hz digital notch filter into your signal processing circuit to attenuate power line interference, which is a major source of noise in capacitive measurements [12].

- Ensure Stable Contact: Design a sensor housing that maintains consistent and firm contact with the skin without restricting movement or blood flow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between capacitive current and faradaic current?

A1: Faradaic current is the current generated by the transfer of electrons between the electrode and an analyte in a redox reaction (e.g., the oxidation of guanine in DNA). This current is the signal of interest in drug analysis. Capacitive current is a non-faradaic current required to charge the electrode-solution interface (the electrical double layer), just like charging a capacitor. It does not involve electron transfer and appears as a large, sloping background that can obscure the faradaic signal [11] [10].

Q2: Why is Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) better than Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for analyzing drugs in low concentrations?

A2: DPV is a pulsed technique designed to minimize the contribution of capacitive current to the measurement. By sampling the current just before the potential pulse is applied and subtracting it from the current during the pulse, DPV effectively filters out the capacitive background. This results in a much higher signal-to-noise ratio, making it possible to detect and quantify redox signals from drugs at very low concentrations, which is crucial for pharmaceutical studies [11].

Q3: How does electrode modification with alkanethiols help in sensitive detection?

A3: Alkanethiols form a self-assembled monolayer on gold electrodes that acts as a molecular insulator. This layer:

- Passivates the Surface: It chemically blocks interfering reactions, such as oxygen reduction.

- Reduces Capacitive Current: It significantly lowers the non-faradaic background.

- Enables Selectivity: The monolayer can be engineered to selectively allow the target molecule (e.g., dopamine) to reach the electrode while excluding interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid) [10].

Q4: Our lab is new to drug-DNA interaction studies. What is the most reliable electrochemical indicator of binding?

A4: A decrease in the voltammetric peak current of the drug upon addition of DNA is a primary and reliable indicator. When a drug molecule binds to the large DNA helix, its diffusion coefficient decreases dramatically, leading to a drop in the observed current. Additionally, a shift in the peak potential can indicate the binding mode; a positive shift often suggests intercalation, while a negative shift may suggest electrostatic binding [11].

The following table summarizes key electrochemical performance data from recent studies on materials and methods relevant to controlling capacitive and faradaic signals.

Table 1: Electrochemical Performance of Selected Materials and Methods

| Material / Method | Key Parameter | Performance Value | Context & Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkanethiol-NPG IDEs [10] | Signal Enhancement | High redox amplification | Enabled selective detection of dopamine in the presence of ascorbic acid by reducing capacitive background. |

| LaMnO₃–CeO₂ (70:30) [13] | Specific Capacitance | 637.6 F g⁻¹ @ 1 A g⁻¹ | Composite electrode material for charge storage; high capacitance underscores the need to distinguish faradaic from capacitive currents. |

| cEMG Sensor (Micropore) [12] | Skin-Electrode Capacitance | 54.17 pF | Using a stable insulator like micropore bandage provides a consistent and low capacitive baseline for biomedical sensing. |

| Voltammetric Techniques [11] | Sensitivity | High sensitivity for drug-DNA binding | DPV and CV are favored for their ability to detect binding through changes in current and potential, requiring a stable capacitive background. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To functionalize a nanoporous gold (NPG) interdigitated electrode (IDE) with an alkanethiol monolayer to reduce capacitive background and interference.

Materials:

- Nanoporous gold interdigitated electrodes (NPG-IDEs)

- Alkanethiol solution (e.g., 1 mM solution of 1-hexanethiol or 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid in ethanol)

- Absolute ethanol

- Nitrogen (N₂) gas stream

Procedure:

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Clean the NPG-IDEs electrochemically in a standard supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M H₂SO₄) via cyclic voltammetry (e.g., from -0.2 to 1.5 V) until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

- Monolayer Formation: Immerse the clean, dry NPG-IDEs in the 1 mM alkanethiol solution in ethanol. Allow the self-assembly process to proceed for a minimum of 2 hours at room temperature.

- Rinsing and Drying: Remove the electrodes from the thiol solution and rinse them thoroughly with a stream of pure ethanol to remove any physically adsorbed thiol molecules.

- Drying: Gently dry the modified electrodes under a stream of nitrogen gas.

- Validation: Characterize the modified electrode using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in a solution containing a redox probe like 1 mM potassium ferricyanide. A successful modification is indicated by a significant reduction in capacitive background current and a maintained, well-defined faradaic peak compared to an unmodified electrode.

Objective: To utilize the sensitivity of Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPT) to study the interaction between a pharmaceutical compound and DNA and calculate the binding constant.

Materials:

- Pharmaceutical compound (electroactive)

- Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA, e.g., from calf thymus)

- Buffer solution (appropriate pH and ionic strength, e.g., acetate buffer)

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE)

- Electrochemical workstation with DPV capability

Procedure:

- Baseline Measurement: Prepare a solution containing a fixed concentration of the drug in the chosen buffer. Record a DPV scan over a potential window that encompasses the drug's oxidation or reduction peak.

- Titration with DNA: To the same solution, add small, increasing aliquots of a concentrated DNA stock solution. After each addition, allow the solution to equilibrate for a few minutes, then record the DPV signal.

- Data Collection: Continue the titration until no further changes in the voltammetric signal are observed.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the change in peak current (ΔI) or the ratio of bound/free drug concentration against the DNA concentration.

- Fit the data to an appropriate binding isotherm model (e.g., McGhee-von Hippel model) to calculate the binding constant (K).

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Differentiating Capacitive and Faradaic Currents

Drug-DNA Binding Modes and Electrochemical Impact

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Redox-Based Drug Analysis Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A standard working electrode for voltammetry of pharmaceuticals [11]. | Wide potential window, good chemical inertness. |

| Nanoporous Gold (NPG) Electrodes | A substrate for modification; high surface area can be passivated to reduce capacitance [10]. | High surface area, tunable porosity. |

| Alkanethiols (e.g., 1-Hexanethiol) | Used to form self-assembled monolayers on gold electrodes to reduce capacitive current and block interferents [10]. | Forms a dense, insulating molecular layer. |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | An electrochemical technique that minimizes the contribution of capacitive current to the measurement [11]. | High sensitivity for low-concentration analyte detection. |

| Potassium Ferricyanide | A standard redox probe for characterizing electrode surface activity and cleanliness. | Reversible, well-understood electrochemistry. |

| Double-Stranded DNA (dsDNA) | The biological target for drug interaction studies, used to understand the mechanism of action [11]. | Source of guanine and adenine bases for redox reactions. |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) | A common supporting electrolyte that maintains pH and ionic strength, controlling double-layer capacitance. | Biologically relevant pH, inert. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Background Current in Flow Battery Experiments

Issue Description

Experiments on a vanadium redox flow battery (VRFB) system show unusually high and unstable background currents, overshadowing the faradaic signals from the V3+/V2+ and VO2+/VO2+ redox couples. This complicates accurate measurement of electron transfer kinetics. [14]

Potential Causes

- Cause 1: Electrode Contamination. The graphite felt electrode may be contaminated with organic residues or metals from previous experiments, creating a high and unstable surface area for capacitive (non-faradaic) charge storage. [14]

- Cause 2: Unoptimized Electrolyte Composition. The vanadium concentration in sulfuric acid may be too low, or the supporting electrolyte concentration may be insufficient. This increases the solution resistance, which can distort the current signal and accentuate the capacitive contribution. [14] [15]

- Cause 3: Excessive Scan Rate in CV Measurements. Using a scan rate that is too high for the system does not allow the capacitive double-layer to fully charge/discharge between measurements, leading to a large and persistent capacitive current that obscures the faradaic current. [15]

Solutions

Solution 1: Electrode Pre-treatment and Cleaning

- Description: A thermal and chemical cleaning process to remove contaminants and standardize the electrode surface.

- Step-by-Step Walkthrough:

- Thermally treat the graphite felt in an air furnace at 400°C for 6-8 hours to burn off organic impurities. [14]

- Soak the felt in a 1M sulfuric acid solution for 24 hours to dissolve any inorganic residues.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry at 80°C before use.

- Anticipated Outcome: A significant reduction in baseline current noise and more reproducible voltammograms.

Solution 2: Electrolyte Optimization and Characterization

- Description: Adjust the electrolyte composition to improve conductivity and signal clarity.

- Step-by-Step Walkthrough:

- Confirm the concentration of vanadium species (e.g.,

VOSO4) is at least 1.5M in 2-3M sulfuric acid to ensure a strong faradaic signal. [14] - If using non-aqueous systems for asymmetric designs, ensure the supporting electrolyte (e.g.,

LiClO4) concentration is sufficiently high (typically >0.1M) to minimize solution resistance. [15] - Use electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to measure the solution resistance before kinetic experiments.

- Confirm the concentration of vanadium species (e.g.,

- Anticipated Outcome: Lowered solution resistance and a clearer distinction between capacitive and faradaic currents.

Guide 2: Managing Capacitive Interference in Sensitive Biosensor Measurements

Issue Description During the detection of a target analyte (e.g., glucose), the capacitive current from the electric double-layer at the electrode-solution interface dominates the electrochemical response, leading to a low signal-to-noise ratio and poor detection limits.

Potential Causes

- Cause 1: Non-specific Binding. Proteins or other biomolecules in the sample matrix are adsorbing non-specifically to the electrode surface, altering the double-layer structure and increasing capacitance.

- Cause 2: Suboptimal Electrode Material. The chosen electrode material (e.g., gold, glassy carbon) has an intrinsic double-layer capacitance that is large relative to the small faradaic current generated from a low concentration of analyte.

- Cause 3: Incorrect DC Bias Potential. The working electrode is held at a potential close to its potential of zero charge (PZC), where the capacitance is at its maximum and most sensitive to minor changes.

Solutions

Solution 1: Application of a Blocking Layer

- Description: Use a chemical layer to passivate the electrode against non-specific binding.

- Step-by-Step Walkthrough:

- After functionalizing the electrode with the capture probe (e.g., an antibody or DNA strand), incubate it in a 1-2 mM solution of 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (for gold surfaces) or 1% BSA solution for 1 hour.

- Rinse gently with buffer to remove unbound molecules.

- Anticipated Outcome: Reduced non-faradaic current drift and lower background noise.

Solution 2: Pulsed Potential Techniques

- Description: Use chronoamperometry with a double-step potential pulse to separate capacitive and faradaic currents.

- Step-by-Step Walkthrough:

- Apply a potential step from a value where no reaction occurs to a value where the analyte is oxidized/reduced.

- The initial instantaneous current spike is predominantly capacitive. Measure the faradaic current after a short delay (e.g., 50-200 ms) when the capacitive current has decayed.

- Anticipated Outcome: Effective isolation of the faradaic current, improving measurement accuracy for low-concentration analytes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is capacitive current, and why is it a problem in my redox experiments? A1: Capacitive current (or non-faradaic current) is the current required to charge or discharge the electrical double-layer at the electrode-solution interface, much like charging a capacitor. Unlike faradaic current, which involves electron transfer across the interface for a redox reaction, capacitive current does not involve a chemical reaction. It appears as a large, sloping background in techniques like Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), which can obscure the smaller peaks from your target redox species, leading to inaccurate data interpretation. [15]

Q2: In a Vanadium Redox Flow Battery (VRFB), what common factors can lead to an imbalance that increases parasitic capacitive effects? A2: Several factors related to the symmetric design of VRFBs can create imbalances that manifest as increased background currents or inefficiencies: [14] [15]

- Electrolyte Crossover: The migration of different vanadium species (

V2+,V3+,VO2+,VO2+) through the membrane leads to cross-contamination and self-discharge, which can be mistaken for or contribute to capacitive losses. - Kinetic Disparities: The reaction rates at the positive (

VO2+/VO2+) and negative (V3+/V2+) electrodes are often different. This "wooden barrel effect" means the slower reaction limits performance and can be exacerbated by capacitive charging times. - Temperature Sensitivity:

V5+ions are unstable at high temperatures, while other ions precipitate at low temperatures. Operating outside the stable window can cause precipitation, changing the active surface area and capacitive behavior of the electrodes. [14]

Q3: Are there system designs that inherently minimize capacitive interference? A3: Yes, asymmetric RFB designs are a promising research direction. By using different chemistries or materials at the positive and negative electrodes, these systems can be engineered for higher kinetics and reduced crossover, which indirectly helps manage capacitive effects by providing a more stable and efficient faradaic process. Examples include zinc-iron and vanadium-manganese RFBs. [15]

Q4: How can I actively control for capacitive currents in my data analysis? A4: A standard method is to perform Background Subtraction.

- Record a cyclic voltammogram of your system in your supporting electrolyte without the electroactive species present. This captures your capacitive background current.

- Record a second voltammogram under identical conditions with your electroactive species present.

- Subtract the first background voltammogram from the second. The result is a voltammogram primarily representing the faradaic current of your redox species.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Electrode Activation for Capacitive Current Minimization

Objective: To clean and activate a glassy carbon working electrode for reproducible electrochemical measurements.

Materials: Glassy carbon electrode (3 mm diameter), alumina polishing slurry (1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm), deionized water, ultrasonic bath, K3Fe(CN)6/K4Fe(CN)6 solution.

Methodology:

- Polishing: On a microcloth pad, polish the electrode surface sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm alumina slurry. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water after each polish.

- Sonication: Sonicate the electrode in deionized water for 5 minutes to remove any adhered alumina particles.

- Electrochemical Activation: In a solution of 1 mM

K3Fe(CN)6/K4Fe(CN)6in 0.1M KCl, perform cyclic voltammetry between -0.2 V and +0.8 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 100 mV/s until a stable, reproducible voltammogram with a peak separation (ΔEp) close to 59 mV is achieved. Validation: A well-activated electrode will show aΔEpof 59-70 mV for theFe(CN)6^{3-/4-}couple, indicating fast electron transfer kinetics and a clean surface with stable capacitance.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Capacitive and Diffusive Contributions via Scan Rate Studies

Objective: To deconvolute the capacitive and faradaic current contributions in a porous electrode material.

Materials: Test electrode, potentiostat, electrolyte with redox couple (e.g., 1M VOSO4 in 2M H2SO4).

Methodology:

- Mount the electrode in a cell and record a series of cyclic voltammograms at progressively increasing scan rates (e.g., 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 mV/s).

- At a specific potential, plot the measured current (i) against the scan rate (v) and the square root of the scan rate (v^{1/2}). Data Analysis:

- The current response typically follows the power law:

i = a*v^b. - A b-value of 0.5 indicates a current dominated by semi-infinite linear diffusion (ideal faradaic behavior).

- A b-value of 1.0 indicates a current dominated by surface-controlled processes (ideal capacitive behavior).

- The total current can be quantified as

i(V) = k1*v + k2*v^{1/2}, wherek1*vis the capacitive contribution andk2*v^{1/2}is the diffusive (faradaic) contribution.

Table 1: Current Components at Different Scan Rates in a Model System

| Scan Rate (mV/s) | Total Current (µA) | Capacitive Current (µA) | Faradaic Current (µA) | % Capacitive Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 15.2 | 4.5 | 10.7 | 29.6% |

| 50 | 45.1 | 22.5 | 22.6 | 49.9% |

| 100 | 72.5 | 45.0 | 27.5 | 62.1% |

Table 2: Key Reagents for Controlling Capacitive Effects

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Graphite Felt | Standard high-surface-area electrode for flow batteries; its porosity is a major source of capacitance that must be controlled. [14] |

| Sulphuric Acid | Supporting electrolyte for VRFBs; increases conductivity, reducing IR drop and associated current distortions. [14] |

| Ion Exchange Membrane | Separates half-cells; its selectivity and resistance impact self-discharge and overall cell efficiency, relating to capacitive losses. [14] [15] |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol | A passivating agent for gold electrodes in biosensors; forms a self-assembled monolayer to block non-specific binding and stabilize capacitance. [16] |

| Alumina Polishing Slurry | For electrode surface preparation; a reproducible, smooth surface minimizes variable capacitive background currents. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Electrochemical Data Optimization Workflow. This chart outlines the decision-making process for diagnosing and resolving high capacitive current issues, guiding researchers to the relevant troubleshooting sections.

Diagram 2: Root Causes of High Capacitive Currents. A cause-and-effect diagram mapping common experimental factors that lead to problematic capacitive contributions in redox systems.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Low Specific Capacitance

Problem: Your supercapacitor cell is exhibiting lower than expected specific capacitance. Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-optimal Electrolyte | Perform Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in different electrolytes to compare current response. | Switch to an electrolyte with higher ionic conductivity and smaller solvated ion size. For example, use NaOH instead of KOH for cubic Cu₂O [17]. |

| Restacked 2D Electrode Materials | Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to check for reduced interlayer spacing. | Incorporate spacer nanoparticles (e.g., BiFeO₃, CoFe₂O₄) between nanosheets to prevent stacking and maintain accessible surface area [18]. |

| Surface Impurities on Electrode | Use X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to detect surface contaminants. | Implement a H₂-assisted thermal treatment (500-800°C) to remove surface hydrocarbons and other impurities [19]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Rapid Capacity Fade During Cycling

Problem: The device shows a significant drop in capacity over multiple charge-discharge cycles. Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable Electrode-Electrolyte Interface | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to monitor increasing charge transfer resistance over cycles. | Ensure electrolyte pH is compatible with the electrode material. Acidic/alkaline electrolytes can destabilize certain materials like δ-MnO₂ or Ti₃C₂Tx MXene [18]. |

| Structural Degradation of Electrode | Analyze post-cycling electrodes with SEM/XRD for morphological or crystalline phase changes. | Optimize synthesis to create robust morphologies (e.g., cubic shapes) and use composite materials to enhance structural stability [17] [20]. |

| Operation at Low Temperatures | Measure capacitance and ESR at room temperature vs. low temperature. | Use anti-freezing electrolytes (e.g., Water-in-Salt, organic solvent mixtures) designed for low-temperature operation to maintain ion mobility [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 3: High Internal Resistance

Problem: The supercapacitor has high equivalent series resistance (ESR), leading to poor power density and voltage drops. Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Ionic Conductivity of Electrolyte | EIS to measure bulk electrolyte resistance. Use viscometry. | For low temperatures, use electrolytes with lower viscosity (e.g., by adding organic solvents). For room temperature, select electrolytes with high molar conductivity like NaOH [17] [21]. |

| Poor Electronic Conductivity of Electrode | Perform four-point probe measurements on the electrode material. | Integrate conductive additives like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) or reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) to form hybrid composites, enhancing electron transport [20]. |

| Poor Wettability | Contact angle measurements to assess electrolyte spreading on the electrode. | Ensure the electrode material is thoroughly dried and consider using surfactants or surface functionalization to improve electrolyte penetration [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the most critical electrolyte parameter for maximizing capacitance?

While ionic size is often considered, recent interpretable machine learning studies identify electrolyte hydration energy as a more universal and critical descriptor than ionic size alone. Lower hydration energy facilitates easier ion desolvation, allowing ions to get closer to the electrode surface, which significantly enhances the stored charge [22].

FAQ 2: Why is my electrode material performing differently in various research papers?

The performance of an electrode material is not an intrinsic property; it is a system property heavily dependent on the electrolyte used. The table below illustrates how the same material can yield different results. Always compare performance metrics with close attention to the experimental conditions, especially the electrolyte.

Table: Performance Variation of Electrode Materials with Electrolyte Composition

| Electrode Material | Electrolyte | Specific Capacitance | Stability / Retention | Key Reason for Performance Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic Cu₂O [17] | 6 M NaOH | 362.77 F/g | 104% (excellent) | Smaller ESR (0.503 Ω) and more active sites in NaOH. |

| Cubic Cu₂O [17] | KOH | 225 F/g | Not specified | Higher ESR compared to NaOH electrolyte. |

| Ti₃C₂Tx-BFO Nanocomposite [18] | 1 M NaOH | 532 F/g | High coulombic efficiency over 10,000 cycles | Optimal pseudocapacitive performance and low resistance (2.9 Ω). |

| Ti₃C₂Tx-BFO Nanocomposite [18] | 1 M Na₂SO₄ | Lower than NaOH | Not specified | Different ion dynamics and interaction with the nanocomposite surface. |

| Mo₂CTx MXene [18] | H₂SO₄ | 79.14 F/g | Excellent over 5000 cycles | Superior electrochemical performance in acidic medium for this MXene. |

| Mo₂CTx MXene [18] | 1 M KOH | 11.27 F/g | Not specified | Alkaline electrolyte may not be optimal for this material. |

FAQ 3: How can I increase the energy density of my carbon-based EDLC?

Beyond seeking higher surface area carbons, focus on:

- Post-synthesis treatment: H₂-assisted thermal treatment (500-800°C) of activated carbon can remove surface impurities that act as dielectric barriers, improving gravimetric capacitance by up to 28% and energy density by over 35% [19].

- Electrolyte engineering: Using electrolytes with a wider electrochemical stability window (ESW), such as ionic liquids or "Water-in-Salt" electrolytes, allows for a higher operational voltage (V). Since energy scales with E=½CV², this leads to a dramatic increase in energy density [21] [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Studies

This protocol outlines the synthesis of cubic-shaped cuprous oxide and a standard method for evaluating its performance in different electrolytes.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Copper Precursor: Copper acetate monohydrate (Cu(CH₃COO)₂·H₂O)

- Reducing Agent: D-Glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆)

- Precipitating Agent: Sodium hydroxide pellets (NaOH)

- Electrolytes: 6 M Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) and 6 M Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH)

- Electrode Preparation: Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) binder and N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solvent.

Workflow:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve copper acetate monohydrate and D-glucose separately in double-deionized water.

- Reaction: Slowly add the NaOH solution to the copper salt solution under constant stirring. Then, add the D-glucose solution to this mixture.

- Aging & Drying: Allow the resultant sol to age until it forms a gel. Dry the gel to obtain the final Cu₂O powder.

- Electrode Fabrication: Mix active material (Cu₂O), conductive agent (e.g., carbon black), and PVDF binder in a mass ratio (e.g., 80:10:10) using NMP to form a slurry. Coat slurry onto a current collector (e.g., Ni foam) and dry thoroughly.

- Electrochemical Testing: In a three-electrode setup, test the electrode in 6 M KOH and 6 M NaOH separately using CV, GCD, and EIS techniques.

Experimental Workflow for Cu₂O Synthesis and Testing

This protocol describes the creation of a nanocomposite to mitigate the restacking of MXene nanosheets, a common issue that reduces performance.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- 2D Material: Ti₃C₂Tx MXene nanosheets (typically from etching Ti₃AlC₂ MAX phase)

- Spacer Nanoparticles: Bismuth Ferrite (BiFeO₃, BFO) precursors (e.g., Bismuth nitrate, Iron nitrate)

- Electrolytes for Screening: 1 M LiCl, 1 M NaOH, 1 M Na₂SO₄, 1 M MgSO₄

Workflow:

- MXene Preparation: Synthesize a colloidal solution of delaminated Ti₃C₂Tx MXene nanosheets via selective etching of the Al layer from the Ti₃AlC₂ MAX phase.

- Nanocomposite Formation: Mix the MXene suspension with pre-synthesized BFO nanoparticles (or their precursors for in-situ growth) under sonication and stirring. The BFO nanoparticles act as physical spacers.

- Material Characterization: Use XRD and SEM to confirm the successful integration of BFO and the increased interlayer spacing between MXene sheets.

- Electrochemical Screening: Fabricate electrodes from the MXene-BFO nanocomposite and test its performance across the different aqueous electrolytes (LiCl, NaOH, Na₂SO₄, MgSO₄) using CV and GCD to identify the optimal one.

Workflow for MXene-BFO Nanocomposite Electrode

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Supercapacitor Electrode and Electrolyte Optimization

| Item | Function in Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | A common aqueous alkaline electrolyte. Offers high ionic conductivity and can enhance pseudocapacitance in metal oxides. | Optimal electrolyte for cubic Cu₂O (362.77 F/g) and Ti₃C₂Tx-BFO (532 F/g) due to small ESR and good ion accessibility [17] [18]. |

| Activated Carbon | The standard porous electrode material for Electric Double-Layer Capacitors (EDLCs). Provides high surface area for ion adsorption. | Subject to H₂-assisted thermal treatment to remove surface impurities, boosting capacitance by up to 28% [19]. |

| BiFeO₃ (BFO) Nanoparticles | Used as spacer nanoparticles in 2D material composites. Prevents restacking of nanosheets, maintaining high surface area and ion diffusion paths. | Integrated into Ti₃C₂Tx MXene to create nanocomposites, preventing face-to-face restacking and improving performance [18]. |

| Ionic Liquids | Non-aqueous electrolytes with a wide electrochemical stability window (ESW). Used to achieve higher operating voltages and thus greater energy density. | Studied for use in Electrochemical Flow Capacitors and low-temperature systems due to their wide ESW and tunable properties [24] [21]. |

| D-Glucose | Serves as a reducing and structure-directing agent in the sol-gel synthesis of metal oxide nanostructures. | Used in the synthesis of cubic-shaped Cu₂O particles, contributing to the defined morphology and porous structure [17]. |

Measurement and Suppression: Techniques for Controlling Capacitive Interference

FAQs: Capacitance Characterization in EIS

FAQ 1: My Nyquist plot shows a depressed or flattened semicircle, not a perfect one. What does this indicate about my interface?

A depressed semicircle often indicates a non-ideal capacitive behavior at the electrode-electrolyte interface [25]. This deviation from an ideal semicircle (which represents a perfect capacitor) can be caused by:

- Surface Inhomogeneity: The electrode surface may not be uniform. Factors like roughness, porosity, or a distribution of grain sizes lead to a distribution of time constants instead of a single, unique value [25].

- Material Properties: Variations in local conditions, such as temperature or pressure across the sample, can cause this non-ideality [25].

- Modeling Solution: This behavior is typically modeled using a Constant Phase Element (CPE) instead of an ideal capacitor in the equivalent circuit. The CPE has an exponent (n), where n=1 represents an ideal capacitor, and lower values represent the degree of depression.

FAQ 2: How can I tell if my measured EIS data is reliable?

Reliable EIS data comes from a system that is linear, stable, and causal. You can check for these properties:

- Stability (Steady State): The system must be at a steady state throughout the measurement, which can take hours. Drift in the system due to factors like adsorption of impurities, degradation, or temperature change will lead to inaccurate results [26].

- Linearity: Electrochemical systems are inherently non-linear. EIS requires pseudo-linearity, achieved by using a small excitation signal amplitude (typically 1-10 mV) [26]. A linear system should not generate harmonics. Significant harmonic response signals non-linearity, meaning your AC amplitude may be too high.

- Causality: The response you measure must be solely due to the applied input signal and not external noise.

FAQ 3: What is a good number of measurement points per decade to use?

The optimal number is a balance between measurement time and resolving power.

- For simple systems with one or two processes, 5 points per decade may be sufficient [25].

- For more complex impedances with multiple overlapping processes (e.g., in perovskite solar cells), it is advisable to increase this to 10 or more points per decade [27] [25]. A good rule of thumb is that the measurement points should form smooth curves. If you see corners or edges between points, you should increase the number of points per decade [25].

FAQ 4: Should the frequency sweep go from high to low or low to high?

The sweep direction generally does not affect the measured values. However, there are practical reasons to start at high frequency and sweep to low frequency [27] [25]:

- Faster Initial Data: Measurements at high frequencies are faster. You will see the major part of your spectrum (e.g., the solution resistance and the start of the semicircle) more quickly, allowing you to judge the experiment's success early on [25].

- Easier Auto-Ranging: It can be easier for the instrument's auto-ranging algorithm to find the correct current range when starting from high frequencies [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: No Semicircle is Visible in the Nyquist Plot

Symptoms: The Nyquist plot appears as a nearly vertical line or a severely truncated curve with no discernible semicircular arc.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The system is dominated by a large capacitive component [28]. | Check the Bode plot. If the phase angle is close to -90° across a wide frequency range, the system is highly capacitive. The semicircle may be at a frequency below your measured range. | Extend the measurement to lower frequencies. Be aware that this significantly increases measurement time. |

| The charge transfer resistance (Rct) is very low. | Check the magnitude of the impedance at the lowest frequency measured. A very low Rct makes the semicircle small and difficult to observe. | Ensure your equivalent circuit model is appropriate. Visually, the semicircle may be compressed against the Y-axis. |

| The time constant of the interfacial process is outside the measured frequency window. | The characteristic frequency (fmax) at the top of the semicircle is given by fmax=1/(2πRctCdl). If your frequency range is too high or too low, you will miss the semicircle. | Widen your frequency range, particularly to lower frequencies, to capture the full relaxation process. |

Problem 2: Unstable or Drifting Impedance Measurements

Symptoms: Poor reproducibility, data points that scatter, or a Nyquist plot where successive measurements do not overlap.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The system is not at a steady state. [26] | Monitor the Open Circuit Potential (OCP) before the EIS measurement. If it drifts significantly, the system is not stable. | Allow more time for the system to equilibrate before starting the EIS experiment. Ensure experimental conditions (temperature, flow, etc.) are constant. |

| The surface of the electrode is changing. [26] | This is common in corrosion or battery studies where films can grow or degrade. | Use a different DC potential or consider a different experimental context. For time-variant systems, split the EIS experiment into multiple, faster sequences over different frequency ranges [29]. |

| The excitation amplitude is too large, causing non-linearity. [29] | Check for harmonic distortions in the output signal. Reduce the AC voltage amplitude and see if the data stabilizes. | Use the smallest AC amplitude that still provides a signal well above the system noise. For galvanostatic EIS, techniques like GEIS-AA can automatically adapt the input current to maintain a constant output voltage amplitude, ensuring linearity [29]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard Protocol: Potentiostatic EIS on a Coated Sample

This protocol outlines a typical 3-electrode EIS experiment, suitable for analyzing the protective properties of a coating [27].

1. Electrode and Cell Setup

- Working Electrode (WE): The sample material under investigation (e.g., a coated aluminum panel). A portion of bare metal must be exposed to make an electrical connection [27].

- Counter Electrode (CE): An inert conductor such as a graphite or platinum rod [27].

- Reference Electrode (RE): A stable reference such as a Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) or Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) [27].

- Electrolyte: An appropriate solution for the study (e.g., 0.5 M NaCl for corrosion testing) [27]. Ensure all electrodes are fully immersed.

2. Instrument Connection Connect the potentiostat leads [27]:

- Working (green) & Working Sense (blue): To the exposed part of the working electrode.

- Reference (white): To the reference electrode.

- Counter (red): To the counter electrode.

- Floating Ground (black): To the Faraday cage, if used, to reduce electrical noise.

3. Software Parameter Configuration Based on the specific experiment, configure the following in the EIS software suite [27]:

- Technique: Potentiostatic EIS.

- DC Voltage: The potential at which the measurement is taken, often the open circuit potential (OCP).

- AC Voltage: A small amplitude signal, typically 1 to 10 mV RMS, to ensure pseudo-linearity [26] [27].

- Frequency Range: Initial Frequency: A high value (e.g., 100 kHz or 1 MHz). Final Frequency: A low value (e.g., 10 mHz or 0.1 Hz) [27] [28].

- Points per Decade: 5-10 points, depending on the complexity of the expected impedance [27] [25].

- Optimize For: Select "Normal" or "Low Noise" for better data quality on high-impedance systems [27].

Workflow: From Experiment to Capacitance Value

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for obtaining the interfacial capacitance from raw EIS data.

Data Presentation: Equivalent Circuit Elements

The table below summarizes the impedance functions of common circuit elements used to model electrochemical interfaces, particularly those involving capacitance.

| Component | Symbol | Impedance (Z) | Physical Meaning in Electrochemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistor | R | Z = R | Represents pure resistance to current flow. Models solution resistance (Rs) or charge transfer resistance (Rct). |

| Capacitor | C | Z = 1 / (jωC) | An ideal capacitor. Models the non-Faradaic charging of the electrical double-layer (Cdl). |

| Constant Phase Element (CPE) | Q | Z = 1 / (Q(jω)n) | A non-ideal capacitor. Models a distributed time constant due to surface roughness or inhomogeneity. n is the exponent (0 ≤ n ≤ 1). |

| Warburg Element | W | Z = σ(1-j) / √ω | Models semi-infinite linear diffusion of ions in the electrolyte. Appears as a 45° line on a Nyquist plot. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat / Galvanostat with FRA | The core instrument. It applies the precise AC potential (or current) and measures the resulting current (or potential) response across the frequency range. The Frequency Response Analyzer (FRA) is the module dedicated to EIS measurements. |

| Working Electrode | The electrode whose interface is being characterized. Its material and surface preparation (e.g., polishing, coating) are critical variables in the experiment. |

| Counter Electrode | An electrode that completes the circuit, allowing current to flow. It is typically made of an inert material like graphite or platinum to avoid introducing side reactions. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured or controlled. Examples: Saturated Calomel (SCE), Ag/AgCl. |

| Electrolyte Solution | The ionic conductor that completes the electrochemical cell. Its composition (type of ions, concentration, pH) and degree of aeration significantly influence the interfacial processes. |

| Faraday Cage | A metallic enclosure that shields the electrochemical cell from external electromagnetic noise, which is crucial for accurate low-current measurements. |

Visualizing the EIS Modeling Process

The diagram below outlines the process of modeling a non-ideal electrochemical interface, which is common when characterizing real-world capacitance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of using pulsed voltammetric techniques like DPV and SWV over continuous scan methods like Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)? Pulsed voltammetric techniques enhance sensitivity and suppress background current by measuring current in a way that minimizes non-faradaic (capacitive) contributions. In DPV, the current is measured twice—just before the pulse and at the end of the pulse—and the difference is plotted, which cancels out a significant portion of the capacitive current [30]. In SWV, the net current is obtained by subtracting the reverse pulse current from the forward pulse current. Because the capacitive current is instantaneous and nearly identical in both forward and reverse pulses, it subtracts out, isolating the faradaic (redox) current [31] [32]. This leads to lower detection limits and improved signal-to-noise ratios.

Q2: My SWV experiment shows no visible redox peak. What parameters should I investigate first? A lack of a visible peak often relates to suboptimal frequency or amplitude settings. A system might show no peak at one frequency but a clear signal at another. You should systematically optimize the square wave parameters [32]:

- Frequency: Explore a wider range of frequencies, as electron transfer kinetics are frequency-dependent.

- Amplitude: Adjust the square wave amplitude; the peak separation (ΔEp) can indicate reversibility and is related to the pulse amplitude [30].

- Potential Step: Ensure the potential step (or increment) is appropriate for your system's redox chemistry. Additionally, verify that your experimental timescale (influenced by parameters like period and sampling width) allows for sufficient faradaic current development [31].

Q3: In the context of capacitive current suppression, what is the key difference between how DPV and SWV measure current? The key difference lies in the pulse waveform and the specific currents used for the differential measurement.

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): A series of small amplitude pulses are superimposed on a linear potential ramp. The current is sampled just before the pulse is applied and again near the end of the pulse. The difference between these two current measurements is plotted versus the applied potential [30]. This minimizes the contribution of the decaying capacitive current.

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV): A high-frequency square wave is superimposed on a staircase waveform. The current is sampled at the end of each forward pulse and at the end of each reverse pulse. The difference between these forward and reverse currents is plotted [31] [32]. This method efficiently cancels capacitive current because the capacitive response is almost identical in both directions.

Q4: Can I use these pulsed techniques for the quantitative analysis of heavy metal ions? Yes, both DPV and SWV are excellent for quantitative trace metal analysis, especially when coupled with stripping voltammetry. The peak current (Ip) is directly proportional to the analyte concentration [30]. For instance, Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) has been used with a bismuth microelectrode to achieve an exceptionally low detection limit of 3.4 × 10⁻¹¹ mol L⁻¹ for Pb(II) ions [33]. The high sensitivity and background suppression of these pulsed techniques make them ideal for such applications [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Peak Resolution or Overlapping Peaks

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inappropriate pulse parameters. A pulse amplitude that is too large can cause peak broadening and overlap.

- Solution: Reduce the pulse amplitude (in DPV) or square wave amplitude (in SWV). For SWV, adjusting the frequency can also help, as higher frequencies can provide better resolution for closely spaced peaks [30] [32].

- Cause: The electrochemical reactions are irreversible.

- Solution: Peak separation in SWV can indicate reversibility. For an irreversible system, the peaks will be broader and less resolved. Optimizing parameters like frequency may help, but the inherent kinetics of the system may limit resolution [30].

Problem 2: High Background Noise or Distorted Signal Shape

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The sampling time is set incorrectly, leading to high capacitive current interference.

- Solution: Ensure the current is sampled near the end of the potential pulse when the capacitive current has decayed significantly. In SWV, the sampling width parameter defines this period [31].

- Cause: Uncompensated solution resistance.

- Solution: If your potentiostat supports it, use iR compensation to correct for voltage drops across the solution [31]. Also, ensure your supporting electrolyte concentration is sufficiently high to provide good conductivity.

Problem 3: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Poor Sensitivity

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Non-optimized parameters for the specific redox system.

- Solution: Systematically optimize key parameters. Refer to the table below for guidance.

- Cause: Electrode fouling.

- Solution: Clean and/or polish the working electrode according to the manufacturer's guidelines. For example, a solid bismuth microelectrode was polished on silicon carbide paper and placed in an ultrasonic bath before measurements to ensure a clean surface [33].

Experimental Parameter Optimization

The tables below summarize the key parameters for DPV and SWV and provide typical starting values for optimization.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Pulse Techniques

| Parameter | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|

| Waveform | Linear ramp with superimposed pulses | Staircase ramp with superimposed square wave |

| Measurement | Difference between pre-pulse and end-of-pulse current | Difference between forward and reverse pulse currents |

| Amplitude | Pulse amplitude (e.g., 10-100 mV) [30] | Square wave amplitude (e.g., 10-50 mV) [31] [30] |

| Scan Rate | Controlled by pulse period and step potential | Controlled by frequency and step potential (increment) |

| Step Potential | Potential increment between pulses (e.g., 2-10 mV) [30] | Potential increment (e.g., 1-10 mV) [31] |

| Pulse Period / Frequency | Pulse duration (e.g., 10-1000 ms) [30] | Square wave frequency (e.g., 5-100 Hz) [31] [32] |

Table 2: Example Parameter Sets for Different Scenarios

| Application Scenario | Technique | Suggested Starting Parameters | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Redox Probe Characterization | SWV | Amplitude: 25 mV; Frequency: 15 Hz; Increment: 5 mV [31] | Well-defined peaks for reversible systems |

| High-Resolution Separation | DPV | Amplitude: 25 mV; Pulse Period: 100 ms; Step Potential: 2 mV [30] | Narrower peaks for distinguishing analytes with close redox potentials |

| Fast Screening | SWV | Amplitude: 25 mV; Frequency: 50 Hz; Increment: 10 mV [32] | Rapid data acquisition with good sensitivity |

| Trace Analysis of Pb²⁺ | DPASV* | Accumulation Potential: -1.4 V; Accumulation Time: 30 s; Pulse Amplitude: 50 mV [33] | High signal for trace metal detection |

*DPASV: Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing SWV for a Reversible Redox Couple

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide to optimizing Square Wave Voltammetry parameters using a standard reversible redox couple, such as potassium ferricyanide.

Objective: To determine the optimal square wave amplitude and frequency for achieving a well-defined, sensitive voltammogram for a reversible system.

Materials:

- Potentiostat capable of SWV

- Standard Three-Electrode Cell:

- Working Electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon Electrode, GCE)

- Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl)

- Counter Electrode (e.g., Platinum wire)

- Solution: 1.0 mM Potassium ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) in 1.0 M KCl (supporting electrolyte)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the GCE with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 μm) on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and sonicate for 1 minute to remove any adhering particles.

- Cell Setup: Place the clean electrodes into the cell containing the ferricyanide solution.

- Initial Parameter Set (Baseline): In your instrument software, open the SWV experiment and set an initial potential of +0.5 V and a final potential of -0.1 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). Use AutoFill or set initial parameters: Amplitude = 25 mV, Frequency = 15 Hz, Increment = 5 mV [31].

- Run the Experiment: Initiate the SWV scan and record the voltammogram.

- Frequency Optimization:

- Keep the amplitude and increment constant.

- Run a series of SWV scans, increasing the frequency (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 25, 50 Hz).

- Observe the change in peak current and peak shape. The peak current will generally increase with frequency, but excessive frequency can lead to distortion if the electron transfer kinetics are not sufficiently fast.

- Amplitude Optimization:

- Set the frequency to the value that gave the best peak shape from step 5.

- Run a series of SWV scans, increasing the amplitude (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 75 mV).

- Observe the peak current and peak separation. For a reversible system, the peak separation should be close to the pulse amplitude. Larger amplitudes give higher peaks but can cause broadening.

- Data Analysis: Plot the peak current versus frequency and amplitude to identify the optimal values that provide the highest signal without distorting the waveform.

Visual Guide: SWV Signal Generation and Optimization

SWV Parameter Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Electrochemical Experiments Featuring Pulse Voltammetry

| Item | Function | Example Application in Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth-based Electrodes | Environmentally friendly alternative to mercury electrodes for metal ion detection; provides a favorable signal-to-background ratio [33]. | Solid bismuth microelectrode (SBiµE) for ultra-trace detection of Pb(II) via DPASV [33]. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Act as stabilizing agents and electrolytes; offer high ionic conductivity and stable electrochemical properties [35]. | BMIM-PF6 used in a Bi₂O₃/IL/rGO nanocomposite to enhance sensor performance for lead detection [35]. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | Nanomaterial providing high surface area and excellent electrical conductivity; enhances electron transfer and sensor sensitivity [35]. | Component in Bi₂O₃/IL/rGO hybrid nanocomposite for sensitive detection of Pb²⁺ ions [35]. |

| Chiral Selectors | Biomaterials (e.g., amino acids, proteins) used to modify electrodes for enantioselective recognition [36]. | L/D-cysteine, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and cyclodextrins used in electrochemical chiral sensors [36]. |

| Vanadyl Sulfate Electrolyte | A single-electrolyte additive enabling multiple redox reactions for energy storage in asymmetric capacitors [37]. | Used in a redox capacitor to utilize all four oxidation states of vanadium [37]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

This guide addresses frequent challenges researchers encounter when working to minimize non-Faradaic (capacitive) currents in electrochemical experiments.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Non-Faradaic Charging Issues

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Method | Solution Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| High & Unstable Background Current | Poor electrode wettability; inhomogeneous surface [38] | Measure contact angle; perform EIS (high, unstable charge transfer resistance) [38] | Apply plasma treatment (O₂, Ar); use hydrophilic binders [39] [38] |