Strategic Selection of Optimal Redox Mediators for Enhanced Electron Transfer in Biomedical and Energy Applications

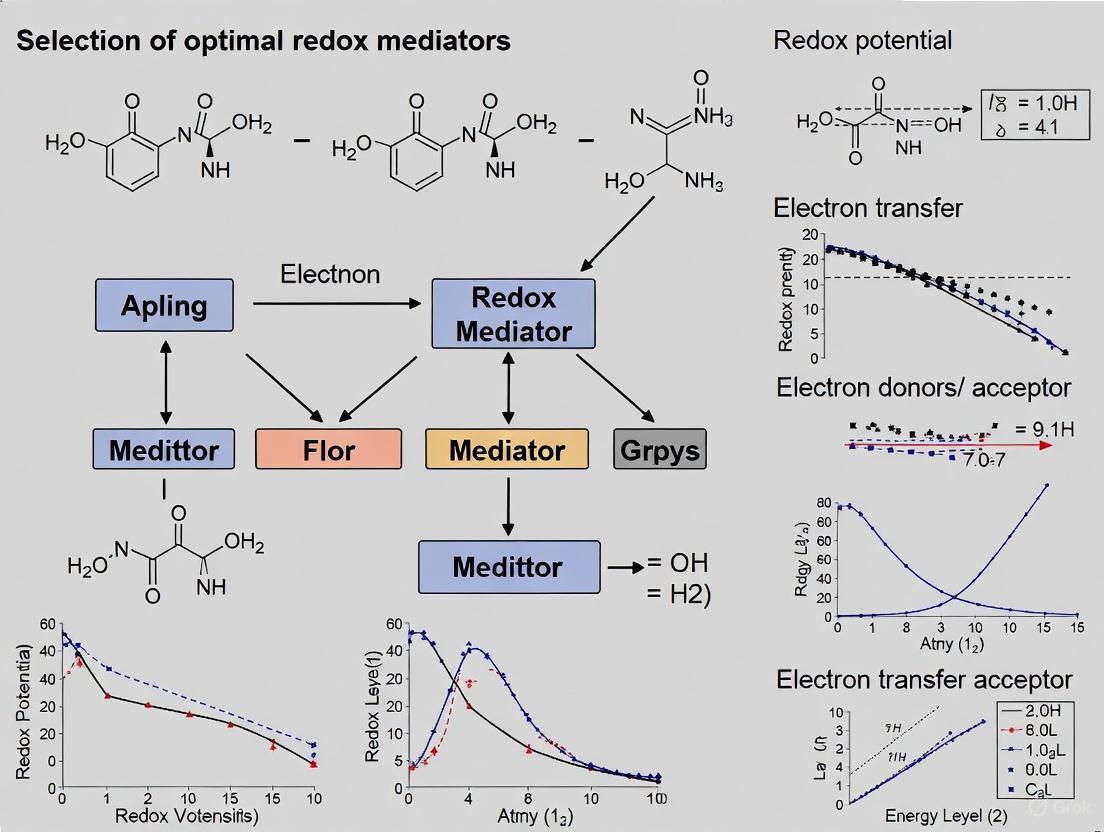

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select and optimize redox mediators (RMs) for efficient electron transfer.

Strategic Selection of Optimal Redox Mediators for Enhanced Electron Transfer in Biomedical and Energy Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select and optimize redox mediators (RMs) for efficient electron transfer. It covers the fundamental principles of RM chemistry, including classification into organic molecules like triarylimidazoles/triarylamines and inorganic complexes such as ferricyanide and metal-organic species. The content explores advanced application methodologies across diverse systems, from aqueous zinc batteries to biophotovoltaic devices, and details critical troubleshooting strategies for common issues like the shuttle effect and self-discharge. By presenting rigorous validation protocols and comparative kinetic analyses of key RM properties—including redox potential, diffusivity, and electron transfer kinetics—this guide enables the rational design and precise matching of redox mediators to specific biomedical and clinical research needs, ultimately optimizing performance and stability in advanced electrochemical systems.

Understanding Redox Mediator Fundamentals: Classification, Mechanisms, and Core Principles

Within the realm of electron transfer research, the selection of an optimal redox mediator is a critical determinant of experimental success. These soluble, redox-active species function as electron shuttles, facilitating charge transfer between electrodes and target materials, thereby enhancing reaction kinetics and efficiency across applications from energy storage to bioelectrocatalysis [1] [2]. This technical support center provides a foundational guide for researchers and scientists navigating the practical challenges of working with redox mediators, framed within the context of a broader thesis on their selection and optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What exactly is a redox mediator and what is its primary function?

A redox mediator is a soluble, redox-active molecule, ion, or complex that acts as a mobile charge carrier or electron shuttle in electrochemical systems [1] [2]. Its primary function is to regulate electrochemical processes by undergoing reversible oxidation and reduction, thereby facilitating electron transfer between an electrode surface and a target compound that may otherwise react slowly or irreversibly [1] [3].

The core mechanism involves a three-stage process:

- The dissolved mediator diffuses to the electrode surface where it is preferentially oxidized or reduced.

- The activated mediator then diffuses to the target material and drives its chemical conversion via electron transfer.

- The mediator, regenerated to its original state, completes the catalytic cycle [1].

What are the ideal characteristics of an effective redox mediator?

An effective redox mediator should possess several key properties to ensure efficient and reliable performance [3] [2]:

- Fast Electron Transfer Kinetics: Rapid heterogeneous electron transfer with the electrode and homogeneous electron transfer with the target analyte.

- High Electrochemical Reversibility: The mediator should maintain stability over many redox cycles without degradation.

- Well-Defined Redox Potential: The potential should be situated between the oxidation and reduction potentials of the active materials to be thermodynamically feasible [1].

- Robust Stability: Both the oxidized and reduced forms of the mediator must be chemically stable in the electrolyte solution for extended use.

- High Solubility and Diffusivity: Sufficient solubility in the electrolyte and good diffusivity are required for efficient mass transport.

What are the common side effects of using redox mediators and how can they be mitigated?

The most common side effects are the shuttle effect and self-discharge [1].

- The Shuttle Effect: This occurs when the oxidized form of the mediator, generated at the electrode, diffuses to the opposite electrode and is reduced back before it can react with the intended target, creating a short-circuit and causing continuous capacity loss.

- Self-Discharge: The mediator can spontaneously react with the electrode materials even when the cell is at rest, leading to a gradual loss of stored energy.

Mitigation Strategies: Suppression solutions include optimizing the concentration of the mediator, modifying the separator membrane to hinder crossover, and engineering the surface of the electrode to minimize unwanted interactions [1].

How does the choice of redox mediator impact biological systems in bioelectrochemistry?

The concentration of redox mediators is crucial in biological studies. Research has shown that as the concentration of common mediators like ferrocyanide/ferricyanide, ferrocene methanol, and tris(bipyridine) ruthenium(II) chloride exceeds 1 mM, significant cellular stress can occur. This manifests as increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduced cell viability across various human cell lines [4]. Therefore, for bioanalytical studies on live cells, mediator concentrations should be carefully optimized and kept as low as possible to ensure accuracy and maintain cellular health [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing an Electrochemical Cell with No or Unusual Response

This guide is based on general electrochemistry handbooks and good measurement practices [5].

Guide 2: Resolving Poor Performance with a Redox Mediator

If your system is functioning but not achieving the desired catalytic performance or stability, follow this guide.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry Characterization of a Redox Mediator

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for electrochemically characterizing a new redox mediator, as employed in recent studies [3].

1. Reagents and Instrumentation:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat capable of performing Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

- Electrochemical Cell: A standard three-electrode cell (gas-tight for oxygen-sensitive studies).

- Electrodes:

- Working Electrode: Glassy Carbon (e.g., ∅ = 6 mm).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl or Li/Li+ (compatible with electrolyte).

- Electrolyte: High-purity solvent (e.g., diglyme, water) and supporting electrolyte (e.g., 1 M LiTFSI, 0.1 M phosphate buffer) [3] [6].

- Redox Mediator: Purified sample (e.g., sublimation for TEMPO) [6].

2. Procedure:

- Preparation: Assemble the cell in an inert atmosphere glovebox if using air-sensitive materials. Polish the working electrode with alumina slurry and clean thoroughly.

- Baseline Measurement: Fill the cell with the electrolyte solution (without mediator) and run a CV scan to establish a baseline.

- Mediator Measurement: Add a known concentration (e.g., 10 mM) of the redox mediator to the electrolyte.

- Data Acquisition: Run CV scans at various scan rates (e.g., from 10 mV/s to 200 mV/s) and under different conditions (e.g., under argon vs. oxygen) to study electron transfer kinetics and stability [3] [6].

- Analysis: Determine the formal redox potential (E0'), peak separation (ΔEp), and assess electrochemical reversibility from the CV curves.

Quantitative Data on Common Redox Mediators

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Redox Mediators and Their Applications

| Mediator | Class | Key Characteristics | Common Applications | Reported Performance / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEMPO & Derivatives [6] | Organic Nitroxide | Redox potential ~3.5 V vs. Li/Li+; High electrochemical reversibility | Li-O2 batteries, Organic synthesis | Effectively reduces charging overvoltages; Various derivatives allow for fine-tuning of properties. |

| Phenothiazine Derivatives (M1, M2) [3] | Organic | Proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET); Superior performance & stability compared to some conventional mediators. | Biosensors, NADH oxidation | Exhibited high electrochemical reversibility and efficient catalytic oxidation of NADH. |

| Fe(CN)63-/4- [7] | Inorganic Complex | Well-defined, reversible redox couple; Low cost. | Aqueous batteries, Redox flow batteries, Electrocatalysis | Used to enhance electrocatalytic performance of surface-active ionic liquids for sensing and oxygen reduction. |

| I3-/I- [1] | Inorganic | Effective redox couple for specific systems. | Aqueous Zn-S batteries | Improves battery kinetics and reversibility by mediating polysulfide conversion. |

| Quinones (e.g., AQDS) [8] [2] | Organic | Two-electron, proton-coupled electron transfer; Tunable potentials. | Redox Flow Batteries, Bioremediation | Attractive for flow batteries due to fast kinetics and high capacity; can be derived from abundant resources. |

Table 2: Impact of Redox Mediator Concentration on Cell Health (in vitro) [4]

| Mediator | Concentration | Impact on Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) | Impact on Cell Viability | Recommendation for Bio-studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferro/Ferricyanide (FiFo) | > 1 mM | Significant increase | Plummets | Use concentrations below 1 mM and optimize for minimal cellular impact. |

| Ferrocene Methanol (FcMeOH) | > 1 mM | Significant increase | Plummets | Use concentrations below 1 mM and optimize for minimal cellular impact. |

| Tris(bipyridine) Ru(II) (RuBpy) | > 1 mM | Significant increase | Plummets | Use concentrations below 1 mM and optimize for minimal cellular impact. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Mediator Experiments

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | The central power source and measurement device for applying potential/current and measuring electrochemical response. | Used in all cited experimental studies for CV and battery cycling [3] [6]. |

| Three-Electrode Cell Setup | Provides a controlled electrochemical environment with separate working, counter, and reference electrodes for accurate measurements. | Standard setup for characterizing mediators, e.g., with Glassy Carbon working electrode [3]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides ionic conductivity in the solution, minimizes ohmic resistance, and ensures the electric field is uniform. | LiTFSI in diglyme for non-aqueous systems [6]; Phosphate buffer for aqueous bio-systems [3]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable and known reference potential against which the working electrode is poised. | Ag/AgCl (aqueous), Li/Li+ (non-aqueous) [3] [6]. Critical for constant potential experiments. |

| Dummy Cell | A simple resistor (e.g., 10 kΩ) used to replace the electrochemical cell for initial instrument and lead troubleshooting [5]. | Essential first step in diagnosing a system with no response. |

This technical support guide provides a comparative analysis of organic and inorganic redox mediators, crucial components for facilitating electron transfer in electrochemical and bioelectrochemical systems. Redox mediators act as molecular shuttles, transporting electrons between electrodes and chemical or biological species, enabling and enhancing various processes from organic synthesis to biosensing. This resource assists researchers in selecting optimal mediators and troubleshooting common experimental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between organic and inorganic redox mediators?

Organic redox mediators are carbon-based molecules whose redox activity typically comes from organic functional groups. Common classes include viologens, triarylamines, quinones, and ferrocene derivatives [9]. Their properties, such as redox potential, can be finely tuned through synthetic modification of their molecular structure [9].

Inorganic redox mediators are metal-based compounds or complexes. Examples include metalocene complexes (e.g., cobaltocenes), ferricyanide, and cerium or ruthenium complexes [9] [10] [11]. Their redox activity is centered on the metal ion, and their potential is influenced by the metal's identity, its oxidation state, and the surrounding ligands.

Table: Fundamental Characteristics of Organic and Inorganic Redox Mediators

| Characteristic | Organic Redox Mediators | Inorganic Redox Mediators |

|---|---|---|

| Core Composition | Carbon-based molecular structures [9] | Metal-centered ions or complexes [9] [10] |

| Redox Center | Organic functional groups (e.g., quinone, viologen) [9] | Metal ion (e.g., Fe, Co, Ru, Ce) [9] [10] [11] |

| Tunability | High (via synthetic modification of molecular structure) [9] | Moderate (via choice of metal center and ligand environment) [9] |

| Common Examples | Methyl viologen, Triarylamines, Quinones [9] [12] | Ferrocene, Cobaltocene, Ferricyanide, Ru(bpy)₃²⁺ [9] [10] [11] |

How do I select a mediator based on redox potential for my system?

Selecting a mediator with the appropriate formal potential (E°) is critical. The mediator's redox potential should be between the potentials of the electron-donating and electron-accepting reactions to be thermodynamically favorable [2].

- Determine the Redox Potential of Your System: Identify the formal potential of the species you wish to oxidize or reduce.

- Choose a Matching Mediator: Select a mediator with a redox potential that bridges the gap between your target species and the electrode. For a reduction reaction, the mediator's potential should be more positive than the target's potential but more negative than the electrode's applied potential.

- Consult Potential Tables: Refer to compiled data for common mediators. All potentials should be compared on a consistent scale, typically versus the Ferrocene/Ferrocenium (Fc/Fc⁺) couple [9].

Table: Redox Potentials of Common Mediators vs. Fc/Fc⁺ [9]

| Mediator | Type | Typical Redox Potential (V vs. Fc/Fc⁺) | Primary Application Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cobaltocenes | Inorganic | -1.9 V to -1.4 V | Strongly reductive electrosynthesis [9] |

| Aromatic Hydrocarbons | Organic | -3.0 V to -0.8 V | Highly reductive conditions [9] |

| Viologens | Organic | -1.1 V to -0.8 V | CO₂/CO enzymatic conversion [12] |

| Ferrocenes | Inorganic | -1.2 V to 1.3 V | Oxidative transformations, reference standard [9] |

| Triarylamines | Organic | 0.8 V to 1.4 V | Oxidative transformations [9] |

Why is my mediated reaction slow or inefficient, and how can I improve the electron transfer rate?

Slow electron transfer can arise from several factors:

- Mismatched Redox Potentials: The driving force (ΔG) may be insufficient if the mediator's potential is too close to that of the target species. Solution: Select a mediator with a more suitably spaced potential [9].

- Poor Electronic Coupling: The mediator and the active site may not interact effectively. Solution: For enzymatic systems, this may require mediator interaction sites on the protein surface [12]. In synthetic systems, ensure the mediator can physically access the reaction site.

- Mass Transport Limitations: The mediator may not diffuse efficiently between the electrode and the reaction site. Solution: Optimize stirring rate or use a flow system. For immobilized systems, a redox polymer can be used to create a "electron-hopping" network [13] [14].

- High Mediator Concentration: In biological assays, high mediator concentrations (>1 mM) can cause cytotoxicity, increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reducing cell viability, which can halt bio-electrochemical processes [10]. Solution: Titrate the mediator to find the lowest effective concentration.

My bioelectrochemical system shows degradation in performance. Could the redox mediator be toxic to my cells?

Yes, cytotoxicity is a significant concern when using redox mediators with live cells. Studies on common cell lines have shown that as the concentration of mediators like ferro/ferricyanide, ferrocene methanol, and tris(bipyridine) ruthenium(II) chloride exceeds 1 mM, ROS increases significantly and cell viability plummets [10].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Dose Optimization: Perform a dose-response assay to find the maximum non-toxic concentration for your specific cell line.

- Mediator Screening: Test alternative mediators with similar redox potentials but potentially lower cytotoxicity.

- Monitor Cell Health: Use independent parameters like ROS quantification, cell migration (scratch assays), and cell growth (luminescence assays) to assess impact [10].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Assessing Electron Transfer Efficiency in a Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reaction

This protocol is adapted from a study using a cobaltocene mediator to achieve high current densities in synthetic electrochemistry [11].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| NiBr₂/dtbbpy | Main nickel catalyst for the cross-electrophile coupling. |

| Bis(ethylcyclopentadienyl)cobalt(II) (Co(CpEt)₂) | Homogeneous electron-transfer mediator. |

| Cobalt Phthalocyanine (CoPc) | Cocatalyst for activating the alkyl halide electrophile. |

| Nafion 115 Membrane | Separates anodic and cathodic chambers in the H-cell. |

| Ni Foam Cathode | High-surface-area working electrode. |

Detailed Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Use a divided H-cell equipped with a Nafion 115 membrane. Fit the cathode chamber with a Ni foam working electrode (1 cm²) and use an Fe rod sacrificial anode.

- Electrolyte Preparation: In the cathode chamber, combine the aryl bromide substrate (e.g., ethyl 4-bromobenzoate, 0.5 mmol), alkyl bromide substrate (e.g., 1-bromo-3-phenylpropane, 0.75 mmol), NiBr₂/dtbbpy (1 mol%), CoPc (2.5 mol%), and Co(CpEt)₂ (10 mol%) in the appropriate solvent/electrolyte system (e.g., DMF/LiClO₄).

- Electrolysis: Perform electrolysis at a constant current of 8 mA (8 mA/cm² current density). Monitor the reaction by techniques like TLC or GC/MS.

- Analysis: After passing the requisite charge (e.g., 2.1 F/mol), work up the reaction mixture. Quantify the yield of the cross-coupled product and calculate Faradaic efficiency using NMR or other analytical methods.

Workflow: Establishing Mediated Electron Transfer

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for establishing an efficient mediated electron transfer system, applicable to both synthetic and bioelectrochemical setups.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Redox Mediators and Their Applications

| Reagent | Type | Key Function & Explanation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viologens (e.g., Methyl Viologen) | Organic | Low-potestential electron shuttle; accepts electrons for enzymatic reduction of gases like CO and CO₂ [12]. | CO dehydrogenase (CODH)-catalyzed conversion of industrial waste gases [12]. |

| Ferrocene & Derivatives | Inorganic | Medium-potential oxidant; reversible one-electron oxidation makes it a stable mediator for oxidative transformations and a common reference standard [9]. | Mediated electro-oxidation of organic compounds; reference electrode calibration [9]. |

| Triarylamines | Organic | High-potential oxidant; facilitates electron transfer for oxidative transformations where a strong oxidant is needed [9]. | Benzylic oxidations and cross-dehydrogenative coupling reactions [9]. |

| Cobaltocenes (e.g., Co(CpEt)₂) | Inorganic | Strong homogeneous reductant; mediates electron transfer to catalytic species in reductive synthesis, enabling high current densities [11]. | Nickel-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling (XEC) reactions [11]. |

| Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻) | Inorganic | Common inorganic oxidant; used in biosensing and bioelectrochemistry, but can be cytotoxic at higher concentrations [10]. | Electron acceptor in some first-generation biosensors; study of cellular redox biology [10]. |

| Redox Polymers (e.g., PTMA) | Organic | Immobilized mediator matrix; enables reagentless biosensing and battery applications by creating a surface for electron-hopping, avoiding diffusional losses [2] [13]. | Cathode catalyst in Li-O₂ batteries; wiring enzymes in third-generation biosensors [2] [13]. |

In electron transfer research, redox mediators are soluble, redox-active species that act as electron shuttles between an electrode and a target material. Their function is crucial in systems where direct electron transfer is kinetically limited or practically challenging. The operation of these mediators follows a consistent, tri-stage mechanism: Diffusion, Reaction, and Regeneration [1].

This mechanism enables redox mediators to regulate electrochemical processes in diverse applications, from energy storage systems like aqueous batteries to synthetic electrochemistry and bioelectrochemical systems [2] [11] [1]. Selecting an optimal mediator requires a deep understanding of this core mechanism and the properties that influence each stage, which is the central thesis of this technical resource.

Detailed Breakdown of the Tri-Stage Mechanism

The tri-stage mechanism forms the functional backbone of all mediated electron transfer processes. The diagram below illustrates the continuous cycle of these three stages.

Stage 1: Diffusion

The process begins when the dissolved redox mediator (RM) in its initial state diffuses from the bulk solution to the surface of the active material (AM) or electrode [1]. The rate of this stage is governed by the mediator's diffusivity and concentration.

Stage 2: Reaction

At the interface, a redox reaction occurs. The mediator undergoes a preferential electrochemical oxidation or reduction relative to the active material [1]. For example, in a charging battery, a mediator would be oxidized at the electrode surface before the active material itself.

Stage 3: Regeneration

The now-activated mediator (e.g., RM⁺ if oxidized) diffuses away from the electrode and drives the chemical conversion of the target active material by transferring its electron (or hole). This returns the mediator to its original redox state, allowing it to diffuse back and complete the cycle [1].

Key Properties of an Effective Redox Mediator

The efficiency of the entire tri-stage process depends on several key physicochemical properties of the mediator. The relationship between these properties and their impact on the mechanism is visualized below.

The ideal characteristics for a redox mediator include [2] [1] [15]:

- Well-Defined Redox Potential: The formal redox potential (E° ) of the mediator must be strategically positioned between the potentials of the electron donor and acceptor to be thermodynamically feasible.

- Fast Electron Transfer Kinetics: Both homogeneous (in solution) and heterogeneous (at the electrode) electron transfer should be rapid, with low activation energy barriers.

- High Reversibility: The mediator should undergo millions of cycles without significant degradation.

- High Solubility and Diffusivity: The mediator must be sufficiently soluble in the electrolyte and possess a diffusion coefficient that supports rapid mass transport.

- Stability: It should be chemically stable in both its oxidized and reduced forms under operating conditions.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My mediated reaction is much slower than expected. What could be the cause? Slow kinetics often originate from a mismatch between the mediator's redox potential and the target reaction, or from slow diffusion. Ensure the mediator's potential is between that of the electron donor and acceptor [1]. For quinone mediators, studies show that the lipophilicity (LogD) and binding affinity to the target enzyme (ΔGcomp) are critical for rate-limiting diffusion steps [15].

Q2: Why does my system suffer from rapid capacity fade or self-discharge? This is frequently due to the shuttle effect, a major side effect of soluble mediators. The activated mediator diffuses to the wrong electrode (e.g., the anode during charging) and undergoes a cross-reaction, leading to continuous self-discharge and low Coulombic efficiency [1]. This is common in battery systems.

Q3: How can I improve the stability and longevity of my mediator? Select mediators known for their stability in your specific electrolyte. For instance, in aqueous batteries, metal complexes like Fe(CN)₆⁴⁻ or organic molecules like functionalized quinones have shown remarkable stability over many cycles [1] [15]. The use of polymer-based or insoluble bifunctional mediators can also mitigate degradation and loss [2].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow Reaction Kinetics | - Mediator potential mismatch.- Slow diffusion.- Poor electron transfer kinetics. | - Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) to check mediator E°.- Vary mediator concentration. | - Select a mediator with a more suitable E° [1].- Increase mediator concentration or temperature. |

| Low Faradaic Efficiency / High Self-Discharge | - Shuttle effect.- Mediator instability/decomposition. | - Track open-circuit potential decay over time.- Use HPLC/MS to analyze mediator integrity. | - Use solid catalysts or polymer-bound mediators [2].- Add a selective membrane or choose a more stable mediator. |

| Incomplete Target Reaction | - Mediator cannot effectively oxidize/reduce the solid phase.- Insufficient mediation cycle time. | - Ex-situ analysis (XRD, NMR) of the active material. | - Choose a mediator with a higher driving force (more extreme E°).- Optimize electrolyte-to-active material ratio. |

| Loss of Mediator Activity Over Cycles | - Chemical decomposition.- Unwanted side reactions with electrolyte. | - Post-mortem analysis of electrolyte. | - Employ mediators with proven stability (e.g., metal complexes [16]).- Modify electrolyte composition. |

Experimental Protocols for Mediator Evaluation

Protocol 1: Screening Redox Mediators via Cyclic Voltammetry

This protocol is used to determine the key electrochemical properties of a candidate mediator.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of your candidate mediator (1-2 mM) in the desired electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M supporting salt in acetonitrile or aqueous buffer). Ensure the solvent is degassed with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Instrument Setup: Use a standard three-electrode cell with a glassy carbon working electrode, a platinum counter electrode, and a suitable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/Ag⁺ for non-aqueous, Ag/AgCl for aqueous).

- Data Acquisition: Run cyclic voltammograms at multiple scan rates (e.g., from 20 mV/s to 200 mV/s). Key metrics to extract:

- Formal Potential (E°'): The midpoint between the anodic and cathodic peak potentials.

- Reversibility: The separation between anodic and cathodic peaks (ΔEp). A small ΔEp (接近 59 mV for a one-electron process) indicates high reversibility.

- Stability: Run multiple cycles and look for decay in the peak currents, which indicates chemical instability.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Mediation Efficiency in a Model Reaction

This protocol assesses the mediator's ability to catalyze a target reaction, using the oxidation of an insoluble nickel complex as an example [17].

- Substrate Deposition: Generate an electrode-adsorbed layer of the insoluble material. For [Ni(PPh₂NPh₂)₂], this is done by electrochemically reducing the soluble [Ni(PPh₂NPh₂)₂]²⁺ complex at a potential of -1.45 V vs. Fc/Fc⁺ for a set time, causing the reduced, insoluble product to deposit on the electrode surface.

- Mediator Testing:

- In a separate cell containing only the electrolyte and the mediator (e.g., 1 mM ferrocene), run a CV.

- Add the mediator to the cell containing the substrate-modified electrode and run a CV.

- Data Analysis: Compare the CVs. A catalytic current (enhanced oxidation current) for the mediator in the presence of the substrate confirms successful mediation. The magnitude of this current enhancement is a direct measure of mediation efficiency [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs common classes of redox mediators and their typical applications, serving as a starting point for selection.

| Research Reagent | Class / Example | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cobaltocenes [11] | Organometallic / Co(CpEt)₂ | Homogeneous electron-transfer mediator in Ni-catalyzed cross-couplings. | Optimal when its redox potential is slightly above the catalyst. Enables high current densities. |

| Quinones [15] | Organic / 1,4-naphthoquinones | Extracellular electron shuttle in bioelectrochemical systems. | Performance strongly correlates with lipophilicity (LogD) and binding free energy. |

| Iodide/Iodine (I⁻/I₃⁻) [16] [1] | Inorganic / Halogen | Classic redox mediator in dye-sensitized solar cells and aqueous batteries. | Can be corrosive and contribute to shuttle effects in batteries. |

| Ferrocene [17] | Organometallic / Fc/Fc⁺ | Model mediator to study kinetics; used to oxidize insoluble molecular deposits. | Highly reversible and stable. Easy-to-modify potential via functional groups. |

| Ferrocyanide [1] | Inorganic / [Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻ | Redox mediator in aqueous Zn-S batteries, catalyzes sulfur reduction. | High solubility and stability in aqueous electrolytes. |

| Metal Complexes [16] | Coordination Complex / Co(bpy)₃²⁺ | High-efficiency mediator in next-generation dye-sensitized solar cells. | Tunable potential and kinetics via ligand choice. |

Advanced Concepts: Property-Driven Performance

Recent research on quinone mediators for bioelectrochemical systems has quantitatively identified the properties most critical for performance. A library of 40 quinones revealed that lipophilicity (LogD) and the computed free energy of binding to the target enzyme (Ndh2, ΔGcomp) significantly correlated with extracellular electron transfer activity [15]. This underscores that while redox potential is a necessary condition, molecular properties affecting diffusion and binding can be dominant, rate-limiting factors. This principles can be applied when designing or selecting mediators for other systems, guiding researchers to optimize for multiple properties simultaneously.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the fundamental properties of an ideal redox mediator? An ideal redox mediator should possess several key properties: well-defined electron stoichiometry, a known and suitable formal potential (redox potential), fast homogeneous and heterogeneous electron transfer kinetics (reversibility), and stability in both oxidized and reduced forms. Its redox potential must be positioned between the oxidation and reduction potentials of the active materials it is designed to interact with to ensure thermodynamic feasibility. [1] [2]

Why is the redox potential of a mediator critical, and how do I select the right one? The redox potential of the mediator is a primary descriptor of its catalytic activity. It determines the thermodynamic driving force for electron transfer. For the mediator to function effectively, its redox potential must be carefully matched to the energy levels of the reaction it is meant to catalyze. For instance, in a system using a BiVO₄ photocatalyst, the mediator's potential must lie between the catalyst's conduction band and the water oxidation potential (between 0.18 V and 1.23 V vs. SHE) to enable the reaction. [1] [18] Selecting a mediator with an unsuitable potential will lead to inefficient catalysis or no reaction at all.

What does "reversibility" mean in the context of redox mediators, and why is it important? Reversibility refers to the mediator's ability to undergo rapid and repeated oxidation and reduction cycles with minimal kinetic barriers or degradation. A highly reversible mediator exhibits fast electron exchange rates, which is crucial for sustaining catalytic cycles over time. This is often observed in cyclic voltammetry as a small separation between anodic and cathodic peaks. High reversibility ensures the mediator can be efficiently regenerated, maintaining its catalytic function throughout an experiment or charge-discharge cycle. [1] [19] [18]

What are common side effects of using redox mediators, and how can they be mitigated? Two major side effects are the shuttle effect and self-discharge. [1] The shuttle effect occurs when mobile mediator molecules diffuse away from the intended electrode and undergo parasitic reactions, leading to capacity loss and reduced efficiency. [1] [19] Self-discharge happens when the mediator inadvertently oxidizes or reduces a cell component during storage. Mitigation strategies include using electrolyte additives, specialized separators, or immobilizing the mediator on the electrode surface to prevent its diffusion. [1] [19]

How does mediator concentration impact biological experiments? In bioanalytical studies, mediator concentration is a critical optimization parameter. Exposure to concentrations exceeding 1 mM of common mediators like ferrocyanide/ferricyanide (FiFo), ferrocene methanol (FcMeOH), or tris(bipyridine) ruthenium(II) chloride (RuBpy) has been shown to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) and significantly decrease cell viability across various human cell lines. It is crucial to use the lowest effective concentration to minimize cytotoxic effects and ensure experimental accuracy. [20]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Coulombic Efficiency or Slow Reaction Kinetics

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Mismatched Redox Potential. The mediator's redox potential is not properly aligned with the target reaction.

- Solution: Characterize the redox potentials of your active materials. Select a mediator whose redox potential lies between the oxidation and reduction potentials of these materials. Computational screening, such as calculating ionization energies (IE) or HOMO energies, can help identify mediators with suitable potentials. [1] [2]

- Cause 2: Slow Electron Transfer Kinetics. The mediator does not have sufficiently fast redox kinetics.

- Solution: Choose mediators known for rapid electron exchange. Polyoxometalates (POMs), for example, can exhibit quick redox kinetics and cooperative proton-electron transfer. [18] Check electrochemical reversibility via cyclic voltammetry.

- Cause 3: Insufficient Mediator Concentration.

Problem: Rapid Performance Fade or Capacity Loss

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Shuttle Effect. Soluble mediator molecules diffuse to the counter electrode, causing cross-talk and capacity loss.

- Cause 2: Mediator Instability. The mediator decomposes over time, losing its functionality.

- Solution: Investigate the chemical stability of the mediator in your specific electrolyte. For instance, DBDMB decomposes in linear carbonate solvents like EMC but is more stable in cyclic carbonates like EC and PC. Ferrocene can be sensitive to oxygen, requiring an oxygen-free environment for long-term stability. [21]

Problem: Unintended Side Reactions in Biological Systems

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Cytotoxicity of the Redox Mediator. The mediator or its oxidized/reduced forms are harmful to cells.

- Solution:

- Concentration Assessment: Perform a dose-response study. Use assays for ROS production (e.g., fluorescence flow cytometry with CellROX stain), cell viability (e.g., luminescence-based assays), and cell migration (e.g., scratch assays) to determine a safe concentration threshold. [20]

- Mediator Selection: Choose mediators and concentrations that show minimal impact on cell health. For the mediators tested, concentrations should typically be kept below 1 mM. [20]

- Solution:

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Quantitative Data for Common Redox Mediators

| Mediator / Property | Redox Potential (V vs. stated reference) | Key Application Notes | Stability & Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| I₃⁻/I⁻ | ~0.55 V [18] | Used in aqueous Zn-S batteries; reduces voltage hysteresis. [1] | Shuttle effect, can cause self-discharge. [1] |

| Fe(CN)₆⁴⁻/³⁻ | ~0.48 V [18] | Electrocatalytic performance enhancer in SAIL systems. [7] | Can ion-pair with cationic SAIL head groups. [7] |

| Ferrocene (Fc) | ~3.45 V vs. Li/[Li⁺] [21] | Used in SECM for battery research. [21] | 91% reversible oxidation; decomposes with O₂; stable in EMC. [21] |

| DBDMB | ~4.1 V vs. Li/[Li⁺] [21] | Overcharging agent and redox mediator for SECM. [21] | Anodically stable up to ~4.2V; decomposes in EMC; stable in EC/PC. [21] |

| Polyoxometalates ({P₂W₁₅V₃}) | ~0.6 V [18] | Multi-electron (3e⁻) mediator for decoupled water splitting. [18] | High stability, fast kinetics, and proton-coupled electron transfer. [18] |

| Tetrathiafulvalene (TTF-1) | 1st oxidation: ~0.1-0.2 V [19] | SAM-immobilized OER electrocatalyst. [19] | Stable in SAMs on ITO; current loss on rougher FTO. [19] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Potassium Ferrocyanide/Ferricyanide (FiFo) | Classic inorganic redox couple for bioelectrochemistry and electrocatalysis studies. [20] [7] |

| Ferrocene Methanol (FcMeOH) | Common organic redox mediator for bioanalytical techniques like SECM. [20] |

| Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) Chloride (RuBpy) | Used in electrochemiluminescence (ECL) and as a photosensitizer. [20] [18] |

| Tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) Derivatives | Electron donor molecule with two stable oxidation states; used in Li-O₂ batteries and as SAMs for OER. [19] |

| Polyoxometalates (POMs) | Molecular clusters with multi-electron redox capability and tunable potentials; used in energy storage and water splitting. [18] |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Linkers | Molecules with a surface grafting group (e.g., triethoxysilane) for covalent immobilization of mediators on electrodes. [19] |

Workflow: Selecting and Testing a Redox Mediator

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for the selection and experimental validation of a redox mediator for a specific application.

Protocol: Immobilizing a Redox Mediator via Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs)

Objective: To covalently attach a redox mediator to an electrode surface (e.g., ITO or FTO) to mitigate the shuttle effect.

Materials:

- Electrode substrates (ITO, FTO)

- Redox mediator functionalized with a terminal triethoxysilane group (e.g., TTF-1 or TTF-2) [19]

- Dry toluene

- Inert atmosphere glovebox

Method:

- Substrate Cleaning: Clean the ITO/FTO substrates thoroughly (e.g., with solvents, oxygen plasma).

- SAM Formation: Immerse the freshly cleaned substrate in a 1 mM solution of the redox mediator in dry toluene inside an inert atmosphere glovebox.

- Incubation: Heat the solution to 80°C for the first 3 hours, then allow it to incubate at room temperature for 24 hours. [19]

- Rinsing and Drying: Remove the substrate from the solution, rinse it with clean toluene to remove physisorbed molecules, and dry it under a stream of nitrogen.

- Characterization: Characterize the modified electrode using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to confirm the presence of key elemental signatures (e.g., S, Si) and using cyclic voltammetry (CV) to confirm the retained redox activity of the immobilized layer. [19]

Protocol: Assessing Mediator Cytotoxicity

Objective: To evaluate the impact of a redox mediator on cell health for bioelectrochemical experiments.

Materials:

- Mammalian cell lines (e.g., HeLa, Panc1, U2OS, MDA-MB-231)

- Redox mediator stock solution

- Cell culture reagents (DMEM, FBS, etc.)

- CellROX Green oxidative stress stain

- RealTime-Glo MT Cell Viability Assay reagents

- Flow cytometer

- Microplate reader for luminescence

Method:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in appropriate plates and allow them to adhere and grow to 80-90% confluence.

- Mediator Exposure: Expose cells to a range of mediator concentrations (e.g., from µM to mM) for a set duration (e.g., 6 hours).

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Quantification:

- Stain cells with CellROX Green (5 µM) for 30 minutes.

- Lift the cells, and analyze using fluorescence flow cytometry. Use unstained controls for gating. [20]

- Cell Viability/Growth Assay:

- Use a luminescence-based viability assay (e.g., RealTime-Glo) according to manufacturer instructions.

- Monitor luminescence over time to track cell proliferation and viability in the presence of the mediator. [20]

- Data Interpretation: Compare ROS levels and viability metrics against an untreated control. A safe mediator concentration should not significantly increase ROS or reduce cell viability and growth.

Understanding HOMO and LUMO Energy Levels

What are HOMO and LUMO, and why are they critical for redox mediators?

In molecular orbital theory, the HOMO (Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital) is the highest-energy orbital that contains electrons, while the LUMO (Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital) is the lowest-energy orbital that can accept electrons [22] [23]. Collectively, they are known as the frontier molecular orbitals and define the boundary between occupied and unoccupied electron states in a molecule [22]. For redox mediators, these orbitals are fundamental because:

- The energy of the HOMO determines the molecule's ability to donate an electron (its oxidation potential) [22] [23].

- The energy of the LUMO determines the molecule's ability to accept an electron (its reduction potential) [22] [23].

- Electron transfer often involves the flow of electrons from the HOMO of an electron donor (e.g., a microbial cell) to the LUMO of an electron acceptor (e.g., an electrode), and a redox mediator facilitates this by acting as a shuttle [24].

What does the HOMO-LUMO gap tell me about a potential mediator?

The HOMO-LUMO gap is the energy difference between these two orbitals. It serves as a key indicator of a molecule's electronic and optical properties [22] [23].

- Stability and Reactivity: A larger HOMO-LUMO gap generally indicates higher kinetic stability and lower reactivity. A smaller gap often enhances reactivity and is typical in conjugated systems [23].

- Optical Absorption: The gap determines the minimum energy required for a molecular electronic excitation. This correlates to the wavelengths of light the molecule can absorb, which can be measured experimentally via UV-Vis spectroscopy [22] [23].

- Proxy for Band Gap: In molecular systems, the HOMO-LUMO gap is analogous to the band gap in solid-state semiconductors, playing a similar role in determining electronic properties [22].

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of how a mediator functions by aligning its energy levels between a donor and an acceptor to facilitate electron transfer.

Determining HOMO/LUMO Energy Levels: A Practical Guide

What are the standard experimental methods for characterizing HOMO/LUMO energies?

Accurately determining the energy levels of your candidate mediators is a crucial first step. The table below summarizes the primary experimental techniques.

| Method | What It Measures | How It Relates to HOMO/LUMO | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) [22] | Oxidation and reduction potentials of the molecule in solution. | HOMO energy ≈ -(Eox + 4.8) eV; LUMO energy ≈ -(Ered + 4.8) eV (vs. vacuum). | Provides electrochemical gap; values are solvent-dependent. |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy [22] [23] | The energy of the lowest-energy electronic absorption peak. | The absorption onset gives an estimate of the HOMO-LUMO gap. | Measures optical gap, which can differ from the electrochemical gap. |

| Photoelectron Spectroscopy (PES) [22] | The energy required to remove an electron from an occupied orbital. | Directly measures the HOMO energy (ionization potential). | Typically used for occupied levels (HOMO); requires vacuum conditions. |

What computational approaches can I use for initial screening?

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a widely used quantum mechanical method for calculating the electronic structure of molecules, including HOMO and LUMO energies [22] [23]. It is excellent for high-throughput virtual screening of mediator candidates before synthesis or purchase. However, note that standard DFT functionals often underestimate the HOMO-LUMO gap; more advanced functionals or post-Hartree-Fock methods may be needed for higher accuracy [23].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: My mediator shows poor electron transfer efficiency.

- Cause 1: Energy Level Misalignment. The mediator's LUMO is too low (too stable) to accept electrons from the biological donor, or its HOMO is too high to effectively donate electrons to the target acceptor. The energy barrier is too large [22].

- Solution: Select a mediator with a LUMO energy closer to (but still below) the HOMO of the electron donor. Use cyclic voltammetry to experimentally verify the redox potentials.

- Cause 2: Solvent Interference. The solvent cage (the configuration of solvent molecules around the mediator) can slow down electron departure and impact transfer efficiency [25].

- Solution: Consider solvent polarity. In aqueous systems, this is a inherent factor. For non-aqueous systems, screen different solvents to find one that optimizes electron transfer kinetics.

Problem: Inconsistent results between computational predictions and experimental data.

- Cause: The inherent limitations of the computational method (e.g., DFT's self-interaction error) or neglecting solvation effects in the calculations [23].

- Solution: Use computational data for relative ranking of molecules, not absolute energy values. Employ solvation models in your DFT calculations to better mimic the experimental environment. Always calibrate your computational method with known experimental data for a similar class of molecules.

Problem: The mediator is unstable and degrades over time.

- Cause: A very small HOMO-LUMO gap can indicate low kinetic stability, making the molecule susceptible to unwanted side reactions or decomposition [23].

- Solution: Choose a mediator with a sufficiently large HOMO-LUMO gap to ensure operational stability, even if it means a slight trade-off in transfer rate. Perform stability tests under operational conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

This table lists key materials and their functions for experiments involving redox mediators.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Standard Redox Mediators (e.g., Quinones, Methylene Blue, Ferrocene derivatives) | Function as benchmark compounds with known HOMO/LUMO levels to validate experimental setups or for comparative studies [24]. |

| Electrolyte Salt (e.g., KCl, Na₂SO₄, TBAPF₆) | Provides ionic conductivity in electrochemical cells for techniques like cyclic voltammetry. The choice depends on the solvent (aqueous vs. non-aqueous). |

| Working Electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon, Gold, Platinum) | The surface where the redox reaction of interest occurs. The material choice can affect electron transfer kinetics. |

| Potentiostat | The electronic instrument that controls the potential of the working electrode in a three-electrode cell and measures the resulting current, essential for CV. |

| UV-Vis Cuvettes | Disposable or reusable containers, typically quartz or plastic, for holding liquid samples during absorption spectroscopy measurements. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can I use the HOMO-LUMO gap to predict the color of my mediator? A: Yes. The HOMO-LUMO gap corresponds to the energy of the photon the molecule can absorb. A small gap (absorbing in the visible range) will result in a colored compound, while a large gap (absorbing only in the UV) will appear colorless [22] [23].

Q: How does molecular conjugation affect the HOMO-LUMO gap? A: Increasing conjugation length systematically lowers the HOMO-LUMO gap. This is a fundamental principle from the particle-in-a-box quantum mechanical model. Extending the π-electron system raises the HOMO energy and lowers the LUMO energy, reducing the gap and shifting absorption to longer wavelengths [23].

Q: What is "s-p mixing" and when should I consider it? A: s-p mixing is a phenomenon in some diatomic molecules (like B₂, C₂, N₂) where molecular orbitals of the same symmetry formed from 2s and 2p atomic orbitals interact, changing the expected order of orbital energies [26] [27]. For most complex organic mediators used in bioelectrochemistry, this effect is less critical, but it is essential for accurate MO diagrams of small diatomics.

Q: How do electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups alter HOMO/LUMO energies? A: Electron-donating groups (e.g., -NH₂, -OCH₃) typically raise the HOMO energy more than the LUMO energy, narrowing the gap. Electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -NO₂, -CN) significantly lower the LUMO energy, also narrowing the gap. This is a primary strategy for tuning mediator properties [23].

Advanced Implementation: Tailoring Redox Mediators for Specific Biomedical and Energy Systems

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is a redox mediator (RM) and how does it fundamentally work in an aqueous battery? A redox mediator (RM) is a soluble, redox-active species that acts as an electron shuttle between the electrode and the solid active materials in a battery [28]. Its function follows a three-stage process:

- The dissolved RM diffuses to the surface of an active material particle (e.g., MnO2 or S).

- The RM undergoes preferential electrochemical oxidation or reduction at the electrode surface.

- The oxidized/reduced RM then diffuses to the active material and drives its chemical conversion via electron transfer, regenerating itself in the process [28]. This mechanism transforms a slow solid-solid electrochemical reaction into a faster electrochemical-chemical reaction cycle.

Q2: I am experiencing significant capacity fade in my Zn-MnO2 battery due to "dead Mn." How can a redox mediator help? "Dead Mn" refers to electrochemically inactive MnO2 that has lost electrical contact with the electrode or becomes electrically isolated due to poor conductivity [29] [30]. This leads to irreversible capacity loss. A redox mediator solves this by chemically dissolving this "dead" MnO2. The RM (e.g., Fe²⁺ or I⁻) diffuses to the isolated MnO2 particles and reduces them back to soluble Mn²⁺ ions via a chemical reaction, effectively recovering the lost capacity and improving cycling stability [30].

Q3: The redox mediator I introduced is causing self-discharge. What is the mechanism and how can I mitigate it? Self-discharge caused by RMs is typically due to the shuttle effect [28]. This occurs when the oxidized form of the RM (e.g., I₃⁻ or Fe³⁺) shuttles to the anode and is chemically reduced by the anode material (e.g., Zn), consuming the charged state without providing useful energy. Mitigation strategies include:

- Potential Matching: Select an RM with a redox potential that is not too close to the anode's potential, reducing the thermodynamic driving force for the parasitic reaction [28] [30].

- Membrane Engineering: Use ion-selective membranes that can hinder the diffusion of the RM species towards the anode [28].

- Functional Additives: Employ additives in the electrolyte or on the separator that can trap or deactivate the RM species before they reach the anode [28].

Q4: For a given aqueous battery system, how do I select the right redox mediator? Selecting the right RM requires balancing several factors [28] [30]:

- Thermodynamic Prerequisite: The RM's redox potential must be properly positioned between the cathode and anode potentials. To facilitate discharge, the RM's potential should be lower than that of the cathode material (e.g., MnO₂) to provide a driving force for the chemical reaction, but not so low that it causes energy loss or anode shuttling [30].

- Kinetic Requirement: The RM must have fast electron transfer kinetics with both the electrode and the active material. A high exchange current density is desirable.

- Solubility and Stability: The RM must be highly soluble in the aqueous electrolyte and chemically stable over long-term cycling.

- System Compatibility: Each aqueous battery system (e.g., Zn-S, Zn-MnO₂) often requires an exclusive RM tailored to its specific chemistry and challenges [28].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Coulombic Efficiency | Shuttle effect of the RM leading to self-discharge [28]. | Re-optimize RM concentration; consider using a more selective membrane; select an RM with a higher redox potential [28]. |

| Poor Rate Capability | Slow kinetics of the RM itself or its reaction with the active material [30]. | Select an RM with faster kinetics (e.g., Fe²⁺/³⁺ over Br⁻/Br₂); enhance electrolyte conductivity [30]. |

| Rapid Capacity Fade | Ineffective prevention of "dead" active material formation; RM decomposition [29]. | Verify RM is functioning correctly to re-dissolve deposits; check RM stability via techniques like UV-Vis spectroscopy [30]. |

| Voltage Hysteresis | Slow conversion reaction kinetics of the active material (e.g., S to ZnS). | Introduce an RM (e.g., I⁻/I₃⁻) to catalyze the solid-liquid conversion reaction, reducing overpotential [28]. |

| Gas Evolution | RM potential may be outside the electrolyte's stability window, triggering water splitting. | Check that the RM's redox potential lies within the electrochemical stability window of your electrolyte system. |

Quantitative Data on Common Redox Mediators

The following table summarizes key performance data for redox mediators discussed in recent literature, providing a basis for comparison and selection.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Common Redox Mediators in Aqueous Batteries

| Redox Mediator | Battery System | Key Function | Reported Performance Improvement | Kinetic Metric (Exchange Current) | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodide (I⁻/I₃⁻) | Zn-S [28], Zn-MnO₂ [30] | Reduces voltage hysteresis, dissolves "dead" MnO₂ | Unlocked areal capacity to 50 mAh cm⁻² in Zn-MnO₂ [30] | 4.26 × 10⁻¹² A [30] | Shuttle effect [28] |

| Iron Ions (Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺) | Zn-MnO₂ [30] | Recovers "dead" MnO₂, dopes MnO₂ to improve kinetics | Achieved 80 mAh cm⁻² areal capacity [30] | 6.31 × 10⁻¹¹ A [30] | Large voltage gap (>500 mV) with MnO₂ causes energy loss [30] |

| Bromide (Br⁻/Br₂) | Zn-MnO₂ [28] | Dissolves MnO₂ deposition layer | Improved long-term cycling stability [28] | 8 × 10⁻¹⁴ A [30] | Poor reaction kinetics [30] |

| Fe(CN)₆⁴⁻ | Zn-S [28] | Catalyzes complete reduction of S | Improved reversibility of Zn-S batteries [28] | Information Not Specified | Shuttle effect [28] |

| Thiourea (TU) | Zn-S [28] | Interacts with ZnS to weaken bond, inhibits SO₄²⁻ formation | Improved reversibility between ZnS and S [28] | Information Not Specified | Information Not Specified |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ as a Redox Mediator in Zn-MnO₂ Batteries

This protocol outlines the steps to incorporate and test the iron ion redox mediator in an aqueous Zn-MnO₂ system to mitigate "dead Mn" and enhance capacity [30].

1. Objective To assess the effectiveness of Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ in recovering capacity by chemically reducing electrochemically inactive MnO₂ and to evaluate its impact on battery kinetics and cycling stability.

2. Materials and Equipment

- Electrode Materials: Zn foil (anode), Carbon felt or other substrate for MnO₂ deposition (cathode).

- Electrolyte: 2 M ZnSO₄ + 0.1 M MnSO₄ in deionized water.

- Redox Mediator: FeSO₄ or (NH₄)₂Fe(SO₄)₂ to introduce Fe²⁺ ions.

- Cell Hardware: Swagelok cell or similar electrochemical cell, separator (e.g., glass fiber).

- Equipment: Electrochemical workstation (potentiostat/galvanostat), UV-Vis spectrometer (for ex-situ analysis).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure Step 1: Cell Assembly and Baseline Testing. a. Prepare the baseline electrolyte without the RM. b. Assemble a Zn-MnO₂ cell and perform galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) cycling at a specified current density (e.g., 1 mA cm⁻²). c. Record the initial capacity and monitor its fade over 10-20 cycles to establish a baseline.

Step 2: Introduction of the Redox Mediator. a. Disassemble the cycled cell. You will observe a deposited MnO₂ layer on the cathode. b. Prepare a fresh electrolyte solution containing, for example, 0.1 M FeSO₄ as the RM. c. Re-assemble the cell using the same electrodes and the new electrolyte with Fe²⁺.

Step 3: Performance Evaluation with RM. a. Continue GCD cycling under the same conditions. b. Observe and record the discharge capacity. A significant increase in capacity compared to the baseline fade indicates successful re-activation of "dead Mn" by the Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ shuttle. c. Continue long-term cycling to assess stability. A high, stable areal capacity (e.g., up to 80 mAh cm⁻²) can be achieved with a functional RM [30].

Step 4: Ex-situ Analysis (Optional). a. After cycling, analyze the electrolyte using UV-Vis spectroscopy to confirm the presence of both Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ species, proving the redox cycling [30]. b. Characterize the cathode surface via SEM/EDS to investigate potential Fe-doping in the MnO₂ layer [30].

4. Data Analysis Compare the capacity retention and areal capacity of the cell before and after the addition of the Fe²⁺ mediator. The successful mediator will show a marked recovery of capacity and improved long-term stability.

Protocol 2: Utilizing I⁻/I₃⁻ to Reduce Voltage Hysteresis in Aqueous Zn-S Batteries

This protocol describes the use of iodide-based RMs to catalyze the slow sulfur conversion reaction, thereby reducing polarization and improving energy efficiency [28].

1. Objective To demonstrate the catalytic effect of the I⁻/I₃⁻ redox couple on the sulfur cathode reaction kinetics in an aqueous Zn-S battery.

2. Materials and Equipment

- Electrode Materials: Zn foil (anode), Carbon-sulfur composite (cathode).

- Electrolyte: 2 M Zn(CF₃SO₃)₂ or similar salt in deionized water.

- Redox Mediator: Iodine (I₂) or Potassium Iodide (KI).

- Cell Hardware: Coin cell or pouch cell hardware, separator.

- Equipment: Galvanostat/Potentiostat.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure Step 1: Control Cell Preparation. a. Prepare a control electrolyte without any RM. b. Assemble the Zn-S cell and perform GCD cycling between a defined voltage window (e.g., 0.2 - 1.8 V). c. Record the voltage profiles and note the voltage difference (hysteresis) between charge and discharge plateaus.

Step 2: Mediator-Integrated Cell Preparation. a. Prepare an experimental electrolyte by adding a small amount (e.g., 50 mM) of KI or I₂ to the base electrolyte. This will form the I⁻/I₃⁻ couple. b. Assemble an identical Zn-S cell using the RM-containing electrolyte.

Step 3: Electrochemical Characterization. a. Run GCD cycles on the experimental cell under identical parameters. b. Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) on both cells at a slow scan rate (e.g., 0.1 mV s⁻¹). Observe the peak separation for the sulfur redox reactions.

4. Data Analysis Compare the voltage hysteresis from GCD and the peak separation from CV between the control and RM-added cells. A successful I⁻/I₃⁻ mediation will result in a narrower voltage hysteresis and reduced peak separation in CV, indicating faster reaction kinetics and lower overpotential [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Redox Mediator Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | Source of I⁻ for I⁻/I₃⁻ redox couple; used to improve kinetics in Zn-S and Zn-MnO₂ systems [28] [30]. | Highly soluble; but can cause shuttle effect. Optimal concentration needs to be determined empirically [28]. |

| Ferrous Sulfate (FeSO₄) | Source of Fe²⁺ ions for the Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ redox couple; effective for recovering "dead Mn" in Zn-MnO₂ batteries [30]. | Fast kinetics; can lead to energy loss due to voltage gap with MnO₂. Prone to oxidation in air [30]. |

| Potassium Ferrocyanide (K₄Fe(CN)₆) | Provides Fe(CN)₆⁴⁻ anions as RMs; used to catalyze the reduction of sulfur in Zn-S batteries [28]. | Offers a different redox potential compared to simple iron ions; stability in acidic conditions should be verified. |

| Thiourea (CH₄N₂S) | Organic RM that interacts with ZnS to weaken bonds and improve reversibility in Zn-S systems [28]. | Functions via a different mechanism (surface interaction) compared to classic electron shuttles [28]. |

| Zinc Sulfate (ZnSO₄) | Common electrolyte salt for aqueous Zn-ion battery systems. | Serves as the source of Zn²⁺ carrier ions; often used with MnSO₄ in Zn-MnO₂ studies. |

| Glass Fiber Separator | Porous membrane to separate electrodes while allowing ion transport. | High wettability with aqueous electrolytes; provides space for electrode deposition/dissolution. |

Diagrams of Mechanisms and Workflows

Redox Mediator Electron Shuttling Mechanism

Experimental Workflow for RM Testing

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why does my biophotovoltaic (BPV) system's current output decline rapidly after a short period of high performance?

Answer: A rapid decline in current, especially after an initial peak, often points to mediator toxicity or instability. Some redox mediators, such as 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ) and [Co(bpy)3]2+ (CoBP), can generate higher current densities than ferricyanide but only for a short duration. These mediators interrupt the natural photosynthetic electron flow, inhibiting cell growth and causing a collapse in performance [31]. Furthermore, the use of broad-spectrum white light at high intensities can cause the degradation of the ferricyanide mediator into toxic cyanide, which disrupts cell viability and leads to system failure [32].

Protocol for Diagnosis:

- Check Mediator Integrity: After a period of operation, use cyclic voltammetry to analyze the electrolyte. A shift in the mediator's redox peaks or the appearance of new peaks can indicate decomposition.

- Cell Viability Assay: Sample the microbial culture from the BPV system and perform a plate count or use a viability stain (e.g., trypan blue) to confirm whether the decline in current correlates with a loss of viable cells.

- Light Source Audit: Ensure you are not using high-intensity white light, which degrades ferricyanide. Switch to monochromatic red light (620 nm), which has been shown to maintain mediator stability and support EET even at very high intensities (up to 1200 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹) [32].

FAQ 2: My BPV system is not achieving the expected power output. What is the most common bottleneck?

Answer: The most common bottleneck is the inefficient transfer of electrons from the photosynthetic electron transport chain (PETC) to the external electrode [33]. This can be due to several factors:

- Competition with Native Electron Sinks: Extracellular electron transfer (EET) competes for electrons with native pathways, particularly the Mehler-like reactions mediated by flavodiiron proteins (Flv1 and Flv3), which act as strong photoprotective electron sinks [34] [35].

- Low Mediator Transport Efficiency: The outer membrane of cyanobacteria like Synechocystis has low permeability, which limits the transport of mediators to the internal electron-carrying complexes [34].

- Suboptimal Mediator Choice: The selected mediator may not be efficiently reduced by the microbial strain in use, or its redox potential may not be well-aligned with the target site on the PETC.

Protocol for Optimization:

- Genetic Engineering: Consider using mutant strains with deactivated competing electron sinks. For example, knocking out the flavodiiron proteins flv2, flv3, and flv4 in Synechocystis has been shown to improve the specific ferricyanide reduction rate by over 275% [34] [35].

- Mediator Screening: Systematically test different mediators. The table below provides a comparative overview of common options.

- System Redesign: Utilize a BPV system with a designed synthetic microbial consortium, where a second microbe (e.g., Geobacter) facilitates electron transfer, circumventing the weak native exoelectrogenic activity of cyanobacteria [33].

FAQ 3: How do I select the best redox mediator for my specific BPV application?

Answer: Selecting a mediator requires balancing current density, stability, and biocompatibility. No single mediator is perfect for all applications. Ferricyanide is often the best option for long-term experiments due to its chemical stability and low biotoxicity, though it may not provide the highest peak current [31]. For short-term, high-current needs, other mediators like quinones may be suitable, but their toxicity must be accounted for. The decision should be guided by the specific goals of your research, whether for sustained environmental sensing or for studying high-rate electron extraction.

Protocol for Selection:

- Define Application Requirements: Determine if your priority is long-term stability or short-term high current.

- Perform Chronoamperometry: Test candidate mediators under identical conditions, measuring current output over time. This will reveal both peak performance and stability.

- Monitor Physiological Impact: Use fluorometric methods (e.g., PAM fluorescence) to assess photosystem II health and ensure the mediator does not cause excessive stress, such as over-reducing the plastoquinone pool [31].

Experimental Data & Reagent Solutions

Quantitative Comparison of Redox Mediators

The following table summarizes key performance data for three representative redox mediators, crucial for evidence-based selection in your research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Redox Mediators in Synechocystis-based BPV Systems

| Mediator | Example Current Density | Impact on Photosynthetic Electron Transport | Biocompatibility & Stability | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferricyanide [31] [32] | Promotes long-term current output | Extracts electrons from ferredoxins downstream of PSI; induces a more reduced plastoquinone pool. | High chemical stability and low biotoxicity; degrades to cyanide under high-intensity white light. | Long-term, stable BPV operation under red light. |

| 1,4-Benzoquinone (BQ) [31] | High, but short-lived | Strongly oxidizes the plastoquinone pool (increases PQ/PQH₂ ratio), interrupting electron flow. | Cytotoxic; interrupts photosynthesis and cell growth. | Short-term experiments requiring high current, where toxicity is acceptable. |

| [Co(bpy)3]2+ (CoBP) [31] | High, but short-lived | Inhibits electron flow from plastoquinone to photosystem I at high concentrations. | Cytotoxic; interrupts photosynthesis and cell growth. | Investigating electron flow around the cytochrome b₆f complex. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Their Functions in BPV Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in BPV Experiments |

|---|---|

| Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻) | Redox mediator; accepts electrons from the photosynthetic electron transport chain and shuttles them to the anode [34] [31]. |

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Model cyanobacterium; a well-characterized photosynthetic organism with available genetic tools [34] [36]. |

| Δflv234 Mutant Strain | Genetically engineered Synechocystis with deactivated flavodiiron proteins; reduces competition for electrons, enhancing EET [34]. |

| BG-11 Medium | Standard growth medium for cyanobacteria, providing essential nutrients and inorganic salts [34]. |

| HEPES Buffer | Buffering agent to maintain stable pH (e.g., 7.5) in the BPV system [34]. |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ferricyanide-Mediated EET Assay

Objective: To quantify the extracellular electron transfer (EET) capability of a photosynthetic microbial strain using ferricyanide as a mediator.

- Culture Preparation: Grow Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (or mutant strains like Δflv234) in BG-11 medium buffered with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) under continuous illumination (e.g., 50 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹) at 30°C [34].

- BPV System Setup: Use a two-electrode BPV configuration. The anode chamber should contain the cyanobacterial culture in a defined surface area. A potentiostat is connected to measure current [36].

- Mediator Addition: Introduce a predetermined concentration of ferricyanide (e.g., 1-5 mM) to the anode chamber. Immediately begin measurement.

- Data Acquisition: Perform chronoamperometry by applying a constant potential to the working electrode and recording the current generated over time, typically through light-dark cycles [36].

- Data Analysis: The steady-state current under illumination, after subtracting the dark current, is representative of the ferricyanide-mediated EET activity.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Mediator Impact on Photosystem II

Objective: To assess the toxicological impact of a redox mediator on the photosynthetic apparatus.

- Sample Preparation: Incubate the microbial culture with the target mediator at the desired concentration for a set period (e.g., 1-2 hours).

- Fluorometric Measurement: Use a Pulse-Amplitude-Modulation (PAM) fluorometer to measure the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of the sample [31].

- Key Parameter Calculation: Determine the Fv/Fm ratio, which indicates the maximum quantum efficiency of Photosystem II (PSII). A significant decrease in Fv/Fm indicates photoinhibition or damage to PSII caused by the mediator.

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the Fv/Fm values of mediator-treated cells against an untreated control culture to quantify the physiological impact.

Visualizing Electron Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Photosynthetic Electron Flow and Mediator Interaction

This diagram illustrates the photosynthetic electron transport chain in Synechocystis and the points where exogenous redox mediators extract electrons.

Diagram 1: Electron extraction by ferricyanide at the ferredoxin node.

BPV Experimental Workflow

This flowchart outlines a standard experimental workflow for setting up and testing a mediator-based BPV system.

Diagram 2: Standard workflow for a BPV experiment.

FAQs on Electrocatalytic Synthesis and Redox Mediators

Q1: What is a redox mediator in electrocatalysis and why is it important? A redox mediator is a substance that facilitates electron transfer between an electrode and a substrate in an electrocatalytic reaction [37]. Instead of the substrate undergoing direct, often inefficient, electron transfer at the electrode surface, it interacts with the mediator, which shuttles electrons more effectively. This is crucial for enhancing reaction control, improving selectivity, preventing electrode passivation, and enabling transformations that are not accessible via direct electrolysis [38]. Mediators can be molecular (like metal complexes or organic molecules) or heterogeneous (like functionalized electrodes) [37].

Q2: My reductive electrosynthesis reaction using a sacrificial magnesium anode is failing. What could be wrong? Failures with sacrificial metal anodes like magnesium are common and can be attributed to several issues [39]:

- Chemical Side Reactions: The reactive metal anode (e.g., Mg) may directly reduce your organic substrate. A classic example is the unintended formation of Grignard reagents from organic halides [39].

- Anode Passivation: The anode surface can become coated with an insulating film, such as a native oxide layer or insoluble byproducts, which halts the oxidation process [39].

- Cation Interference: Metal cations (Mg²⁺) generated from the anode can migrate to the cathode and undergo competitive reduction, consuming electrons intended for your substrate [39].

- Solution: Consider switching to a less reactive anode material like zinc or aluminum, which may be less prone to side reactions and passivation [39].

Q3: How can I induce enantioselectivity in an electrocatalytic reaction? Inducing chirality in electrocatalysis typically requires an external chiral source. The main strategies are [40]:

- Chiral Electrodes: Modifying the electrode surface with a chiral catalyst or polymer (e.g., poly-ʟ-valine or a metal complex with a chiral ligand).

- Chiral Media: Using a chiral supporting electrolyte or co-solvent that interacts with the reactive intermediates.

- Chiral Auxiliaries: Incorporating a chiral moiety directly into the substrate, which is later removed.

Q4: What are the key differences between constant current and constant potential electrolysis?

- Constant Current (Galvanostatic): This simpler setup is good for initial explorations and often gives higher conversion. The tradeoff is potentially lower selectivity, as the potential can increase to drive undesired side-reactions as the concentration of the substrate decreases [41].

- Constant Potential (Potentiostatic): This mode offers superior selectivity by precisely "dialing in" the potential needed to activate your target species while leaving others untouched. However, it requires a reference electrode and conversion may be incomplete as the current drops over time [41].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: No or Low Current Flow

This indicates a break in the electrical circuit or high cell resistance.

- Check Connections: Ensure all cables are securely connected to the potentiostat and electrodes [42].

- Inspect Electrolyte: Verify that a sufficient concentration of supporting electrolyte is dissolved to provide conductivity [41].

- Check Electrode Surface: Look for signs of severe passivation (e.g., a discolored or coated surface). Gently polish or clean the electrodes according to the manufacturer's instructions [39].

- Verify Solvent & Electrolyte Compatibility: Ensure the solvent/electrolyte combination is appropriate for your intended potential window to avoid decomposition.

Problem: Low Product Yield or Selectivity

This can stem from numerous factors related to reaction conditions and mediator selection.

- Optimize Mediator Loading: Test different catalytic loadings of your redox mediator. Both too little and too much can be detrimental.

- Check Applied Potential/Current: Use cyclic voltammetry (CV) to ensure your applied parameters are correctly tuned to the redox events of the mediator and substrate [41].

- Consider a Divided Cell: If your product is unstable at the counter electrode, use a divided cell with a membrane (e.g., Nafion) to separate the anodic and cathodic compartments [41].

- Re-evaluate Mediator Choice: The mediator may not be optimally matched to your substrate. Consult literature and consider mediators with a different redox potential or mechanism of action (e.g., HAT vs. electron shuttle) [37].

Problem: Passivation of Sacrificial Anode

As discussed in FAQ A2, this is a common failure mode in reductive synthesis [39].

- Diagnosis: Visually inspect the anode for a black, grey, or otherwise discolored, non-conductive coating.

- Mechanical Cleaning: Carefully polish the anode surface to remove the passivating layer.

- Anode Pretreatment: Implement a consistent pretreatment protocol (e.g., acid washing, abrasion) before each use to ensure a clean, active surface [39].

- Change Anode Material: If passivation persists, switch to a different sacrificial metal (e.g., from Mg to Zn) that forms less stable passivating layers under your reaction conditions [39].

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Experiments

This often points to issues with reproducibility in setup or reagent quality.

- Control Moisture/Oxygen: Ensure rigorous exclusion of air and moisture, especially when working with radical intermediates or reactive organometallic mediators.

- Standardize Electrode Pretreatment: Establish and consistently follow a protocol for cleaning and pre-treating electrodes before each experiment.

- Calibrate Instrumentation: Ensure your potentiostat is properly calibrated.

- Use Fresh Solvents/Electrolytes: Decomposed solvents or electrolytes can introduce confounding variables.

Experimental Protocols for Key Electrocatalytic Experiments

Protocol 1: Indirect Anodic Oxidation using a Redox Mediator

This protocol outlines a general procedure for an oxidative transformation using a molecular redox mediator, such as TEMPO or a triarylamine [37].

Workflow Diagram: Indirect Anodic Oxidation

Materials:

- Electrochemical Cell: Undivided cell (e.g., 20 mL vial with ports).

- Electrodes: Anode: Carbon felt or Pt plate (working electrode). Cathode: Pt wire (counter electrode).

- Solvent: Dry acetonitrile (CH₃CN) or dichloromethane (DCH₂C).

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (NBu₄PF₆).

- Redox Mediator: e.g., TEMPO (5 mol%).

- Substrate: 0.2 mmol dissolved in 15 mL of solvent/electrolyte mixture.

Procedure:

- Cell Setup: Place the solvent, supporting electrolyte, substrate, and redox mediator into the electrochemical cell. Stir until fully dissolved.

- Electrode Immersion: Immerse the anode and cathode into the solution, ensuring they do not touch.

- Atmosphere: Purge the solution with an inert gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar) for 5-10 minutes.