Standard Reduction Potential Table in Electroanalysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the standard reduction potential table and its critical applications in modern electroanalysis for pharmaceutical science.

Standard Reduction Potential Table in Electroanalysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the standard reduction potential table and its critical applications in modern electroanalysis for pharmaceutical science. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, advanced methodological applications, troubleshooting for complex samples, and validation techniques. The content synthesizes traditional electrochemical theory with cutting-edge advancements, including machine learning-aided predictions and nanotechnology-enhanced sensors, offering a complete resource for leveraging electroanalytical techniques in drug development, quality control, and therapeutic monitoring.

Understanding Standard Reduction Potentials: The Foundation of Electroanalytical Chemistry

Defining Standard Reduction Potential and Standard Electrode Potential

Standard Reduction Potential (E°) and Standard Electrode Potential are fundamental quantitative measures in electrochemistry, representing the inherent tendency of a chemical species to acquire electrons and thereby be reduced [1] [2]. These potentials are defined under standard conditions: a temperature of 298 K, a pressure of 1 atm for gases, and a 1 M concentration for all aqueous species [1]. In the context of electroanalysis research, these values provide a predictive framework for understanding electron transfer processes, which is critical for applications ranging from designing novel sensors to optimizing synthetic electrochemical routes in pharmaceutical development. The standard reduction potential is always written for a reduction half-reaction (gain of electrons), providing a universal reference for comparing the thermodynamic favorability of reduction processes across different elements and compounds [1] [3].

The underlying principle reflects a dynamic equilibrium established at the electrode-solution interface [4]. For a metal electrode M in contact with its ions Mⁿ⁺ in solution, an equilibrium is established: Mⁿ⁺(aq) + n e⁻ ⇌ M(s). The position of this equilibrium determines the charge separation and thus the potential difference. For more reactive metals like magnesium, this equilibrium lies further toward ion formation compared to less reactive metals like copper, resulting in a more negative charge on the metal and a different potential [4]. Since the absolute potential of a single electrode cannot be measured directly, all standard electrode potentials are reported relative to the Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE), which is assigned an arbitrary potential of exactly 0 V [3] [2]. This forms the basis for a comprehensive scale that allows electroanalytical researchers to quantitatively rank chemical species by their oxidizing or reducing power.

Measurement and Experimental Protocols

The Reference Point: The Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE)

The SHE serves as the universal reference point against which all other standard electrode potentials are measured [3]. Its design and operation under standard conditions are fundamental to obtaining reproducible and comparable potential values.

The experimental setup for the SHE consists of a platinum foil electrode immersed in a 1 M H⁺ solution. Hydrogen gas is bubbled over the platinum surface at a pressure of 1 atmosphere. The platinum metal, being chemically inert, serves as a conduit for electrons and catalyses the equilibrium between H⁺ ions and H₂ gas [4].

Experimental Determination of an Unknown Standard Reduction Potential

The standard reduction potential of an unknown species is determined by constructing a galvanic cell where one half-cell is the SHE, and the other contains the species of interest under standard conditions [1] [4]. The potential difference (electromotive force, EMF) of this cell is measured using a high-resistance voltmeter to prevent current flow, which would alter the system from its standard state [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare the Half-Cells: One half-cell is the standard hydrogen electrode. The other half-cell contains the electrode and ionic species for which the standard reduction potential is to be determined (e.g., a copper rod in a 1 M Cu²⁺ solution) [4] [3].

- Connect the System: The two half-cells are connected via a salt bridge (e.g., a glass tube filled with potassium nitrate or potassium chloride solution in agar gel, stoppered with porous cotton wool). The salt bridge completes the electrical circuit by allowing ion flow without significant mixing of the half-cell solutions [4].

- Measure the EMF: A high-resistance voltmeter is connected between the two electrodes. The measured cell potential (E°_cell) is the standard cell potential [4].

- Identify Reaction Spontaneity: The direction of electron flow indicates the spontaneous process. The electrode where reduction spontaneously occurs is the cathode; the electrode where oxidation occurs is the anode [3].

- Calculate the Unknown E°: The standard cell potential is calculated as E°_cell = E°_cathode - E°_anode. Since the SHE has a defined potential of 0 V, the measured E°_cell directly gives the standard reduction potential of the unknown half-cell if it acts as the cathode. If oxidation occurs in the unknown half-cell, its reduction potential is the negative of the measured E°_cell [3].

For example, when a Cu²⁺/Cu half-cell is connected to the SHE, reduction occurs at the copper electrode (cathode), and a voltmeter reads +0.34 V [3]. The calculation is: E°_cell = E°_Cu²⁺/Cu - E°_SHE, so +0.34 V = E°_Cu²⁺/Cu - 0. Thus, E°_Cu²⁺/Cu = +0.34 V [3].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and components of this measurement setup:

Cell Notation

A standardized shorthand notation, known as cell notation or cell diagram, is used to unambiguously describe electrochemical cells [5]. The convention is:

- The anode (oxidation half-cell) is written on the left, and the cathode (reduction half-cell) on the right.

- A single vertical line

|represents a phase boundary (e.g., between solid electrode and aqueous solution). - A double vertical line

||represents the salt bridge. - The concentration of solutions and gas pressures are often specified [5].

For the cell used to measure the copper reduction potential, the notation is: Pt(s) | H₂(g, 1 atm) | H⁺(aq, 1 M) || Cu²⁺(aq, 1 M) | Cu(s) [5] [3]

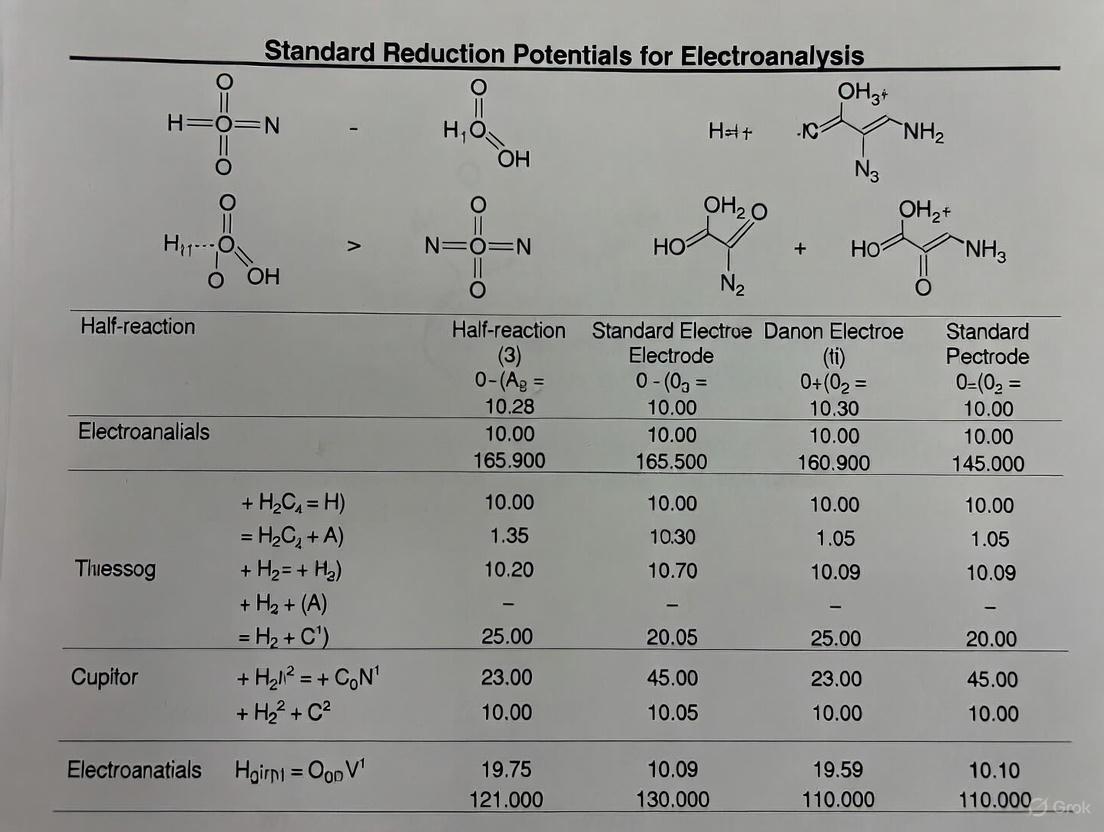

Data Presentation: The Standard Reduction Potential Table

In electroanalysis, the standard reduction potential table is an indispensable tool for predicting the direction and driving force of redox reactions. The following table summarizes selected standard reduction potentials, measured relative to the SHE at 298 K [1] [2].

Table 1: Standard Reduction Potentials at 298 K

| Reduction Half-Reaction | E° (V) |

|---|---|

| F₂(g) + 2e⁻ → 2F⁻(aq) | +2.87 |

| O₂(g) + 4H⁺(aq) + 4e⁻ → 2H₂O(l) | +1.23 |

| Br₂(l) + 2e⁻ → 2Br⁻(aq) | +1.09 |

| Ag⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Ag(s) | +0.80 |

| Fe³⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Fe²⁺(aq) | +0.77 |

| O₂(g) + 2H₂O(l) + 4e⁻ → 4OH⁻(aq) | +0.40 |

| Cu²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Cu(s) | +0.34 |

| 2H⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → H₂(g) | 0.00 (Reference) |

| Zn²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Zn(s) | -0.76 |

| Mg²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Mg(s) | -2.38 |

| Li⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Li(s) | -3.04 |

Interpreting the Table for Electroanalysis

- Predicting Spontaneity: A species with a more positive (or less negative) standard reduction potential has a greater tendency to be reduced and is a stronger oxidizing agent. Conversely, a species with a more negative reduction potential has a greater tendency to be oxidized and is a stronger reducing agent [2]. For any proposed redox couple, the reaction will be spontaneous (and produce a positive E°_cell) when the half-reaction with the higher E° is the reduction cathode, and the one with the lower E° is the oxidation anode [1].

- Calculating Standard Cell Potential (E°cell): The overall standard cell potential for a galvanic cell is calculated using the formula: E°_cell = E°_cathode - E°_anode [1] [3]. This value is directly related to the Gibbs Free Energy change (ΔG°) for the cell reaction by ΔG° = -nFE°_cell, where n is the number of electrons transferred and F is the Faraday constant [2].

- The Activity Series: The table of standard reduction potentials is essentially a quantitative activity series. Metals with highly negative reduction potentials (e.g., Li, Mg) are strong reducing agents and are very reactive, while metals with positive reduction potentials (e.g., Ag, Cu) are more stable and resistant to oxidation [1].

Advanced Considerations and the Nernst Equation

The standard conditions defined for E° are often not met in real-world electroanalysis or biological systems. The Nernst Equation is used to calculate the reduction potential (E) under non-standard conditions, accounting for temperature, and the concentrations (or activities) of the reacting species [6] [2].

The general form of the Nernst equation for a half-reaction is: aA + bB + n e⁻ ⇌ cC + dD

[ E = E° - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \left( \frac{{C}^c {D}^d}{{A}^a {B}^b} \right) ]

Where:

- E is the reduction potential under non-standard conditions.

- E° is the standard reduction potential.

- R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K).

- T is the temperature in Kelvin.

- n is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction.

- F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C/mol).

- The curly braces

{}represent the activities of the species (often approximated by concentrations for dilute solutions) [6].

At 298 K (25°C), the Nernst equation can be simplified to:

[ E = E° - \frac{0.05916}{n} \log \left( \frac{[C]^c [D]^d}{[A]^a [B]^b} \right) ]

The Critical Role of pH

For reactions involving H⁺ or OH⁻ ions, the Nernst equation shows that the reduction potential is heavily dependent on pH [6] [2]. This is critically important in biochemical and pharmaceutical electroanalysis, where the environment is often near pH 7. The standard potential (E°) is defined at pH 0 (1 M H⁺). The formal reduction potential (E°') is often used, which is the potential measured under a defined set of conditions including pH 7 [6].

For example, the reduction potential for the 2H⁺/H₂ couple shifts from 0.00 V at pH 0 to -0.414 V at pH 7 [6]. Similarly, the O₂/H₂O couple shifts from +1.229 V to +0.815 V at pH 7 [6]. Researchers must be vigilant to use the correct standard (SHE at pH 0 or the biochemical standard at pH 7) when consulting different data sources.

Applications in Electroanalysis and Drug Development

Standard reduction potentials are foundational in modern electroanalytical research. The following diagram outlines key application pathways stemming from this fundamental concept:

- Predicting and Optimizing Synthetic Pathways: Electrochemical methods are increasingly used in green synthesis and pharmaceutical manufacturing. The E° values allow researchers to select suitable oxidizing or reducing agents to achieve a specific transformation with high yield and minimal side products, streamlining drug development pipelines [1] [2].

- Sensor and Biosensor Development: The design of electrochemical sensors for clinical diagnostics relies on the predictable redox behavior of analytes. Knowing the E° of a target molecule (e.g., glucose, a specific biomarker) helps in designing electrode systems that operate at optimal potentials for selectivity and sensitivity, enabling point-of-care testing and continuous monitoring [2].

- Computational Prediction of Redox Properties: Modern electroanalysis leverages computational chemistry to predict reduction potentials and electron affinities for novel compounds, saving significant laboratory resources. Recent benchmarking studies show that neural network potentials (NNPs) trained on large datasets, such as OMol25, are achieving accuracy comparable to traditional density-functional theory (DFT) methods for predicting the reduction potentials of organometallic species, accelerating the discovery of new electroactive materials and catalysts [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Electrode Potential Measurements

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) | The primary reference electrode; a platinum electrode in 1 M H⁺ solution with H₂ gas at 1 atm bubbled over it [4] [3]. |

| Secondary Reference Electrodes (e.g., Ag/AgCl, SCE) | More robust and practical reference electrodes for daily laboratory use, with known, stable potentials relative to the SHE [2]. |

| Inert Sensing Electrodes (e.g., Pt, Au, Graphite) | Serve as a platform for electron transfer without participating in the reaction; used to monitor the potential of the solution [2]. |

| High-Impedance Voltmeter/Potentiostat | Measures cell potential without drawing significant current, ensuring an accurate measurement of the open-circuit EMF [4]. |

| Salt Bridge (e.g., KNO₃/KCl in Agar) | Completes the electrical circuit by allowing ion flow between half-cells while minimizing solution mixing [4]. |

| Standard Solutions (1 M) | Solutions of known concentration (1 M) for the ion of interest, required to define standard conditions [1] [3]. |

The Standard Hydrogen Electrode as the Universal Reference Point

The Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) constitutes the fundamental reference point for the entire thermodynamic scale of oxidation-reduction potentials, establishing a zero-volt baseline against which all other electrochemical reactions are measured. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of SHE construction, operational principles, and its critical role in generating standard reduction potential data essential for modern electroanalysis. Within pharmaceutical research, the SHE framework enables precise prediction of redox behavior for drug compounds and metabolites, supports the development of electrochemical sensors for illicit substance detection, and facilitates advanced electrosynthetic methods for medicinal building blocks. This whitepaper details standardized experimental protocols for potential measurement, addresses technical considerations for maintaining reference integrity, and explores emerging applications in pharmaceutical sciences where reliable potential measurements drive innovation in drug discovery and forensic analysis.

The Standard Hydrogen Electrode is a redox electrode that forms the absolute basis for the thermodynamic scale of oxidation-reduction potentials in electrochemistry. By international convention, its standard electrode potential (E°) is defined as exactly zero volts at all temperatures, providing a universal reference against which all other half-cell potentials can be measured [8]. This fundamental definition allows for the creation of a standardized quantitative scale for reduction tendencies, enabling scientists to predict the direction and feasibility of redox reactions across diverse chemical systems.

The SHE achieves this reference status through a carefully defined system consisting of hydrogen gas bubbled at 1 bar pressure through an acidic solution containing hydrogen ions at an activity of 1 M, typically hydrochloric acid, all maintained at 25°C [9]. The electrode reaction occurs at a platinized platinum surface, which catalyzes the reversible redox reaction: 2H⁺(aq, 1 M) + 2e⁻ ⇌ H₂(g, 1 atm) [8]. The selection of platinum is critical due to its chemical inertness, high catalytic activity for proton reduction, high intrinsic exchange current density for the hydrogen reaction, and the excellent reproducibility of the potential with a bias of less than 10 μV between well-constructed electrodes [8].

In electrochemical research, the SHE serves as the cornerstone for determining standard reduction potentials (E°), which represent the inherent tendency of a chemical species to acquire electrons and undergo reduction under standard conditions (298 K, 1 atm, 1 M concentrations) [1]. These standardized values, compiled in extensive reference tables, enable researchers to calculate cell potentials, predict reaction spontaneity, and design electrochemical systems for analytical and synthetic applications without constructing actual hydrogen electrodes for each measurement.

Theoretical Foundation and Electrode Construction

The Nernst Equation for the SHE

The electrochemical behavior of the hydrogen electrode is quantitatively described by the Nernst equation, which relates the electrode potential to the activities of the reacting species. For the hydrogen half-reaction, the general Nernst equation is expressed as:

[E = E^⦵ - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{red}}}{a{\text{ox}}}]

Where E⦵ is the standard electrode potential (defined as 0 V), R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹), T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin, z is the number of electrons transferred (2 for the hydrogen reaction), F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹), ared is the activity of the reduced form (H₂ gas), and aox is the activity of the oxidized form (H⁺ ions) [8].

For the specific case of the hydrogen electrode reaction (2H⁺ + 2e⁻ ⇌ H₂), this becomes:

[E = 0 - \frac{RT}{2F} \ln \frac{p{\mathrm{H2}}/p^0}{a_{\mathrm{H^+}}^2}]

Where pH₂ is the fugacity of hydrogen gas (approximated by its partial pressure), p⁰ is the standard pressure (1 bar), and aH⁺ is the activity of hydrogen ions. Under standard conditions where pH₂ = 1 bar and aH⁺ = 1, the logarithmic term becomes zero and the potential E equals E⦵ = 0 V [8]. At 25°C, the practical form of the Nernst equation for the hydrogen electrode simplifies to:

[E = -0.0591 \left( \mathrm{pH} + \frac{1}{2} \log p{\mathrm{H2}} \right)]

This equation confirms that under standard conditions (pH = 0, p_H₂ = 1 bar), the potential remains at 0 V, while variations in pH or hydrogen pressure will shift the potential according to this relationship.

Electrode Construction and Components

Constructing a reliable Standard Hydrogen Electrode requires careful attention to component selection and assembly:

Electrode Material: A platinum electrode is utilized due to its exceptional properties, including chemical inertness, high catalytic activity for hydrogen oxidation and reduction, and high exchange current density for the hydrogen reaction [8]. The platinum surface is typically platinized (covered with a layer of fine powdered platinum black) to increase the total surface area, improve reaction kinetics, and enhance hydrogen adsorption at the electrode-solution interface [8].

Hydrogen Gas Supply: Ultra-pure hydrogen gas must be bubbled through the solution at exactly 1 bar (100 kPa) pressure to maintain standard conditions [9]. The gas delivery system should include purification traps to remove trace oxygen and other contaminants that could poison the electrode surface.

Electrolyte Solution: The electrode is immersed in an acidic solution containing hydrogen ions with unit activity (a_H⁺ = 1), typically 1 M HCl or other strong acids [9]. The solution must be prepared with high-purity reagents and deoxygenated water to prevent interference.

Thermal Control: The entire assembly must be maintained at 25°C (298.15 K) during measurements, as the Nernst equation includes temperature dependence [8].

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental setup for determining a standard reduction potential using the SHE:

Figure 1: SHE Experimental Setup. This diagram illustrates the complete circuit for determining standard reduction potentials, featuring the SHE with platinized platinum electrode and the test half-cell connected via salt bridge.

Historical Context: SHE vs. NHE vs. RHE

The development of hydrogen electrode standards has evolved through several refinements:

Normal Hydrogen Electrode (NHE): The original reference electrode consisting of a platinum electrode in 1 N strong acid solution with hydrogen gas bubbled at approximately 1 atm pressure [8]. This was the practical standard used in early electrochemical studies.

Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE): The current theoretical standard where the concentration of H⁺ is 1 M, but the H⁺ ions are assumed to have no interaction with other ions (an ideal condition not physically attainable at these concentrations) [8]. This refinement provides a more consistent thermodynamic reference.

Reversible Hydrogen Electrode (RHE): A practical hydrogen electrode whose potential depends on the pH of the solution according to the Nernst equation [8]. The RHE is particularly useful in applications where pH varies, as its scale shifts with pH (E_RHE = 0 V - 0.0591 × pH at 25°C).

Experimental Protocols for Potential Measurement

Determining Standard Reduction Potentials

The procedure for determining an unknown standard reduction potential using the SHE follows a standardized electrochemical cell setup:

Procedure:

- Construct the SHE according to the specifications in Section 2.2, ensuring all components meet standard conditions (1 M H⁺, 1 atm H₂, 25°C).

- Prepare the test half-cell with the species of interest at 1 M concentration in solution and its corresponding pure metal electrode (e.g., for Cu²⁺/Cu, use a copper electrode in 1 M Cu²⁺ solution) [9].

- Connect the two half-cells with a salt bridge filled with potassium nitrate (KNO₃) or potassium chloride (KCl) in agar gel to maintain ionic conductivity while preventing solution mixing [10].

- Connect the electrodes to a high-impedance voltmeter with the SHE connected to the reference terminal and the test electrode connected to the working terminal.

- Measure the cell potential (E°_cell) once a stable reading is established.

- Record the flow of electrons through the external circuit. If electrons flow from the test electrode to the SHE, the test electrode is the anode (oxidation occurs) and its reduction potential is negative relative to SHE. If electrons flow from the SHE to the test electrode, the test electrode is the cathode (reduction occurs) and its reduction potential is positive [9].

Calculation: The standard reduction potential of the test half-cell is calculated based on the measured cell potential and the known polarity. For a copper/copper ion half-cell, the calculation proceeds as follows:

[ \begin{align} E^\circ_{\text{cell}} &= E^\circ_{\text{cathode}} - E^\circ_{\text{anode}} \ +0.34\, \text{V} &= E^\circ_{\text{Cu}^{2+}/\text{Cu}} - E^\circ_{\text{SHE}} \ +0.34\, \text{V} &= E^\circ_{\text{Cu}^{2+}/\text{Cu}} - 0\, \text{V} \ E^\circ_{\text{Cu}^{2+}/\text{Cu}} &= +0.34\, \text{V} \end{align} ]

This experimentally determined value confirms the standard reduction potential for the Cu²⁺/Cu redox couple as +0.34 V [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential Materials for SHE Construction and Potential Measurements

| Component | Specification | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum Electrode | High-purity Pt wire or foil with platinized surface | Provides catalytically active surface for hydrogen reaction | Platinization increases surface area; must be protected from poisoning [8] |

| Hydrogen Gas | Ultra-high purity (99.999%), oxygen-free | Redox active species for reference couple | Must be purified to remove O₂; precisely controlled at 1 bar pressure [8] [9] |

| Acidic Electrolyte | 1 M HCl or H₂SO₄ (aq) | Provides H⁺ at unit activity | High-purity reagents; deoxygenated solutions; activity coefficients considered [9] |

| Salt Bridge | KNO₃ or KCl in 3% agar gel | Ionic conduction between half-cells | Prevents solution mixing; minimizes junction potentials [10] |

| Test Electrodes | Metal foils or wires (Cu, Ag, Zn) | Working electrodes for potential measurement | High purity surfaces; often polished and cleaned before use [10] |

| Test Solutions | 1 M metal ion solutions | Standard conditions for test half-cells | Prepared from high-purity salts; concentration verified [1] |

Troubleshooting and Interference Management

Several factors can compromise SHE performance and measurement accuracy:

Electrode Poisoning: The highly adsorptive platinized platinum surface is susceptible to poisoning by sulfur compounds, arsenic, alkaloids, colloidal substances, and biological materials [8]. These contaminants block active sites and alter electrode kinetics. Prevention includes using high-purity reagents and gases, and maintaining clean glassware.

Oxygen Contamination: Trace oxygen in the hydrogen gas or solution can be reduced at the electrode surface, creating mixed potentials. Oxygen must be removed by sparging solutions with inert gas and using oxygen traps in the hydrogen gas line [8].

Cation Interference: Cations that can be reduced and deposited on the platinum surface (Ag⁺, Hg²⁺, Cu²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Tl⁺) interfere with measurements by modifying the electrode surface [8]. These must be excluded from the reference compartment.

Geometric and Kinetic Factors: Proper platinization technique is critical for achieving high surface area and reproducible kinetics. Aging of the platinum black coating can lead to drift in potential over time, requiring periodic replatinization.

Application in Standard Reduction Potential Tables

The systematic measurement of half-cell potentials against the SHE has enabled the creation of comprehensive standard reduction potential tables, which serve as essential predictive tools in electroanalytical chemistry. These tables arrange half-reactions in order of decreasing reduction potential, creating an "activity series" that predicts the relative oxidizing and reducing strengths of chemical species [1].

Table 2: Selected Standard Reduction Potentials at 25°C [1] [9] [11]

| Half-Reaction | E° (V) | Application Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| F₂(g) + 2e⁻ → 2F⁻(aq) | +2.87 | Strongest common oxidizing agent |

| S₂O₈²⁻(aq) + 2e⁻ → 2SO₄²⁻(aq) | +2.01 | Persulfate etching and polymerization |

| O₂(g) + 4H⁺(aq) + 4e⁻ → 2H₂O(l) | +1.23 | Biological redox processes, corrosion |

| Br₂(l) + 2e⁻ → 2Br⁻(aq) | +1.09 | Halogen-based disinfectants and synthetics |

| Ag⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Ag(s) | +0.80 | Reference electrodes, silver-based therapeutics |

| Fe³⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Fe²⁺(aq) | +0.77 | Iron metabolism, electron transfer mediators |

| O₂(g) + 2H₂O(l) + 4e⁻ → 4OH⁻(aq) | +0.40 | Cathodic reactions in neutral environments |

| 2H⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → H₂(g) | 0.00 | Reference point (SHE) |

| Fe²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Fe(s) | -0.41 | Corrosion processes, iron biochemistry |

| Zn²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Zn(s) | -0.76 | Galvanization, battery technologies |

| Al³⁺(aq) + 3e⁻ → Al(s) | -1.66 | Lightweight alloys, sacrificial anodes |

| Na⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Na(s) | -2.71 | Sodium-ion batteries, strong reducing agent |

| Li⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Li(s) | -3.04 | Lithium-ion batteries, strongest common reducer |

These tabulated values enable researchers to predict cell potentials for any combination of half-cells using the relationship:

[E^\circ{\text{cell}} = E^\circ{\text{cathode}} - E^\circ_{\text{anode}}]

Where E°cathode is the standard reduction potential for the reaction occurring at the cathode, and E°anode is the standard reduction potential for the reaction occurring at the anode [1] [9]. This predictive capability is fundamental to designing batteries, corrosion protection systems, and electrochemical sensors.

SHE in Electroanalysis and Pharmaceutical Research

Electrochemical Sensors for Pharmaceutical Analysis

The reference framework provided by the SHE enables the development of precise electrochemical sensors for pharmaceutical compounds and drugs of abuse. Recent advances demonstrate how electrochemical-based sensors offer significant advantages for forensic and pharmaceutical screening, including portability, sensitivity, and rapid response times [12]. These sensors exploit the characteristic redox potentials of target analytes, which are precisely quantified against the SHE-derived scale.

For instance, electrochemical sensors can detect illicit substances in street samples and biological matrices by measuring oxidation or reduction currents at specific applied potentials. The standardization afforded by the SHE allows for reproducible measurements across different laboratories and instruments, essential for forensic admissibility and quality control in pharmaceutical manufacturing [12].

Advanced Electrosynthetic Applications

The predictive power of standard reduction potentials referenced to the SHE enables sophisticated electrosynthetic methodologies for pharmaceutical building blocks. Recent research demonstrates the electrochemical deutero-carboxylation of acetylenes and cinnamic acids to produce deuterated malonic acids with precise control over both the site and amount of deuteration [13]. These deuterated building blocks are increasingly valuable in drug discovery for creating isotopically labeled compounds with improved metabolic stability and pharmacokinetic profiles.

In these advanced synthetic applications, the SHE reference scale allows researchers to predict and control the redox behavior of complex organic molecules, enabling selective transformations under mild conditions. The precisely controlled deuteration patterns achieved through these methods would be impossible without the fundamental reference framework provided by the SHE [13].

Experimental Workflow in Modern Electroanalysis

The following diagram illustrates how the SHE reference system integrates into contemporary electrochemical research workflows:

Figure 2: SHE in Modern Electroanalysis. This workflow illustrates how the SHE reference framework supports various applications in pharmaceutical research and analytical chemistry.

The Standard Hydrogen Electrode remains the fundamental reference point for electrochemical measurements nearly a century after its introduction, providing an unchanging zero point for the scale of oxidation-reduction potentials. Its continued relevance in modern electroanalysis and pharmaceutical research stems from the robust thermodynamic foundation it provides, enabling precise prediction of redox behavior across diverse chemical systems. As electrochemical methods continue to advance in sensor technology, electrosynthesis, and pharmaceutical analysis, the SHE reference system maintains its critical role in standardizing measurements, validating methodologies, and ensuring reproducible results across the scientific community. For drug development professionals specifically, the SHE-derived potential scale provides essential insights into drug redox metabolism, enables the design of electrochemical detection platforms, and supports innovative synthetic approaches for deuterated pharmaceutical building blocks with tailored pharmacological properties.

This technical guide provides an in-depth framework for interpreting and applying standard reduction potential tables within electroanalysis research. The standard reduction potential (E°) quantitatively predicts the thermodynamic tendency of chemical species to gain electrons, serving as a foundational metric in electrochemical analysis [1]. For researchers in drug development and analytical sciences, mastering this table enables prediction of redox reaction spontaneity, calculation of cell potentials, and design of electrochemical sensors and assays. This whitepaper details the theoretical principles, practical interpretation methodologies, experimental measurement protocols, and specific applications relevant to pharmaceutical and diagnostic research, with particular focus on the extreme potentials exhibited by fluorine and lithium.

The standard reduction potential (E°) is defined as the inherent tendency of a chemical species to acquire electrons and undergo reduction under standard conditions (298 K, 1 atm pressure, and 1 M concentration for solutions) [1]. Measured in volts (V), these potentials are always reported relative to the Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE), which is arbitrarily assigned a potential of 0.0 V [2]. This reference framework allows for the systematic comparison of different redox couples.

In electrochemical terminology, a "reduction potential" always describes the gain of electrons, as shown in the general half-reaction: ( \text{Oxidized Species} + n e^- \rightleftharpoons \text{Reduced Species} ). The corresponding oxidation potential for the reverse reaction is simply equal in magnitude but opposite in sign ( (E^\circ{\text{ox}} = -E^\circ{\text{red}}) ) [1] [14]. The IUPAC convention recommends reporting all potentials as reduction potentials to maintain consistency across scientific literature, eliminating historical confusion between American and European sign conventions [14].

Data Presentation: Standard Reduction Potential Tables

Standard reduction potentials organize redox couples to predict electron flow and reaction spontaneity. The following tables present key values critical for electroanalysis research.

Table 1: Standard Reduction Potentials of Selected Elements (Strongest Oxidizers to Strongest Reducers)

| Standard Cathode (Reduction) Half-Reaction | Standard Reduction Potential E° (volts) |

|---|---|

| ( F_2(g) + 2e^- \rightleftharpoons 2F^-(aq) ) | +2.87 [2] |

| ( Li^+(aq) + e^- \rightleftharpoons Li(s) ) | -3.04 [2] [15] |

| Other Key Potentials for Context | |

| ( S2O8^{2-}(aq) + 2e^- \rightleftharpoons 2SO_4^{2-}(aq) ) | +2.01 [1] |

| ( O2(g) + 4H^+(aq) + 4e^- \rightleftharpoons 2H2O(l) ) | +1.23 [1] |

| ( Ag^+(aq) + e^- \rightleftharpoons Ag(s) ) | +0.80 [1] [2] |

| ( 2H^+(aq) + 2e^- \rightleftharpoons H_2(g) ) | 0.00 [2] (Reference) |

| ( Fe^{2+}(aq) + 2e^- \rightleftharpoons Fe(s) ) | -0.44 [2] |

| ( Al^{3+}(aq) + 3e^- \rightleftharpoons Al(s) ) | -1.68 [16] |

| ( Na^+(aq) + e^- \rightleftharpoons Na(s) ) | -2.71 [2] [15] |

Table 2: Standard Reduction Potentials in Drug Development Research

| Redox Couple | E° (V) | Relevance to Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| ( O2(g) + 4H^+ + 4e^- \rightleftharpoons 2H2O(l) ) | +1.23 | Models oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) chemistry in biological systems. |

| ( Fe^{3+}(aq) + e^- \rightleftharpoons Fe^{2+}(aq) ) | +0.77 | Central to prodrug activation and electron transfer in metalloenzymes. |

| ( Cu^{2+}(aq) + e^- \rightleftharpoons Cu^+(aq) ) | +0.16 | Relevant to copper-based catalysis and the study of cellular redox signaling. |

| ( M^{2+} + 2e^- \rightleftharpoons M ) (Metal Complexes) | Variable | Potentials tuned for electrocatalytic drug synthesis and analytical detection schemes. |

Interpretation and Predictive Power

The standard reduction potential table is a powerful predictive tool. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between a half-cell's potential and its chemical behavior.

Diagram 1: Relationship between E° value and chemical behavior.

The Redox Series from Fluorine to Lithium

- Fluorine (+2.87 V): Occupying the top position in the table, fluorine gas (F₂) has the highest standard reduction potential, identifying it as the strongest oxidizing agent. It possesses an extremely high innate tendency to gain electrons and be reduced to fluoride ions (F⁻) [2]. This powerful oxidizing nature must be considered when developing fluorinated pharmaceutical compounds or using fluorine in synthesis.

- Lithium (-3.04 V): Located at the opposite extreme, lithium metal (Li) has the most negative standard reduction potential, identifying it as the strongest reducing agent. It has a very high tendency to lose electrons and be oxidized to Li⁺ ions [2] [15]. This strong reducing power is exploited in battery technologies for medical devices.

The fundamental rule for predicting spontaneous redox reactions states that a species with a higher (more positive) reduction potential will spontaneously oxidize a species with a lower (more negative) reduction potential [2]. The overall cell potential ((E^\circ{\text{cell}})) for a reaction can be calculated as: (E^\circ{\text{cell}} = E^\circ{\text{cathode}} - E^\circ{\text{anode}}), where a positive (E^\circ_{\text{cell}}) indicates a spontaneous reaction [1].

Experimental Protocols for Measurement

Accurate determination of reduction potentials is fundamental to electroanalysis. The following workflow details the standard experimental methodology.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for determining standard reduction potentials.

Detailed Methodology

- Reference Electrode Preparation: The experiment is conducted relative to a stable reference electrode. While the SHE is the primary standard (Pt electrode in 1.0 M H⁺ solution, bathed in 1.0 atm H₂ gas), more robust reference electrodes like the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) or silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) are typically used for routine laboratory work due to their reliability [2].

- Working Electrode Assembly: The half-cell containing the redox couple of interest is constructed. This involves an inert sensing electrode (typically platinum, gold, or graphite) immersed in a 1.0 M solution of the ions involved in the redox couple [2]. The sensing electrode serves as the platform for electron transfer.

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: The two half-cells are connected via a salt bridge, which allows ion flow to maintain electrical neutrality without mixing the solutions. A high-impedance voltmeter is connected between the two electrodes to measure the potential difference (EMF or (E^\circ_{\text{cell}})) of the cell with minimal current flow [1] [2].

- Potential Measurement and Calculation: The voltmeter reading provides the cell potential directly. Since the reference electrode's potential is known, the standard reduction potential of the unknown couple is calculated. If the SHE is used as the cathode and the unknown as the anode, the measured cell potential equals the reduction potential of the unknown: (E^\circ{\text{unknown}} = E^\circ{\text{cell}}) (because (E^\circ_{\text{SHE}} = 0.0 V)) [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Electrochemical Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Primary instrument for applying controlled potentials/currents and measuring the resulting electrochemical response. Essential for modern voltammetric techniques. |

| Inert Sensing Electrodes (Pt, Au, Graphite) | Provide a surface for electron transfer to or from the analyte in solution without reacting themselves [2]. |

| Stable Reference Electrodes (Ag/AgCl, SCE) | Provide a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured, replacing the fragile SHE for practical work [2]. |

| Salt Bridge (KCl Agar Gel) | Completes the electrical circuit by allowing ion flow between half-cells while preventing solution mixing, minimizing liquid junction potential. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃) | Carries the majority of the current in the solution, minimizes ohmic drop (iR drop), and controls the ionic strength, which affects activity coefficients. |

Advanced Considerations and Non-Standard Conditions

The Nernst equation is indispensable for interpreting reduction potentials under real-world, non-standard conditions encountered in research, such as varying concentrations or pH levels. The equation relates the measured reduction potential ((E{\text{red}})) to the standard potential ((E{\text{red}}^\ominus)) and the activities (approximated by concentrations) of the reacting species [2].

For a general reduction half-reaction: [ aA + bB + hH^+ + ze^- \rightleftharpoons cC + dD ] The Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E{h} = E{\text{red}} = E_{\text{red}}^{\ominus} - \frac{0.05916}{z} \log \left( \frac{{C}^{c}{D}^{d}}{{A}^{a}{B}^{b}} \right) - \frac{0.05916\,h}{z} \text{pH} ]

This equation highlights the critical influence of pH on reduction potentials for reactions involving (H^+) or (OH^-) ions, a factor of paramount importance in pharmaceutical research where redox chemistry occurs at biological pH (7.4) rather than the standard acidic conditions (pH 0) [2]. The slope of the line relating (E_h) to pH is ( \frac{-0.05916h}{z} ), providing a quantitative tool for predicting how potential changes with the acidity of the environment.

Applications in Drug Development and Electroanalysis

Understanding and applying standard reduction potentials is critical for advancing pharmaceutical research.

- Prodrug Design and Activation: A prominent application is the development of redox-activated prodrugs. An inactive prodrug can be designed with a labile group that is cleaved by a specific reducing agent present in target cells (e.g., in hypoxic tumor tissue). The reduction potential difference between the cellular reductant and the prodrug determines the feasibility and rate of activation.

- Electrochemical Biosensors and Assays: Electroanalytical techniques are foundational for diagnostic sensors and high-throughput screening assays. The specific and quantitative detection of analytes—from small molecule metabolites to large proteins—is achieved by measuring the current generated when the analyte is oxidized or reduced at an electrode held at a precise potential, dictated by its standard reduction potential [1].

- Understanding Drug Metabolism and Toxicity: Many drug metabolism pathways involve redox enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450). The standard reduction potential of the drug molecule or its metabolites provides insights into its likelihood of undergoing oxidation or reduction in vivo, which can predict metabolic stability, potential for reactive metabolite formation, and mechanism-based toxicity.

The standard reduction potential table, anchored by the extreme values of fluorine and lithium, provides an indispensable quantitative framework for predicting and controlling electron transfer reactions. Its rigorous interpretation—from the fundamental ranking of oxidizing/reducing power to the application of the Nernst equation under biologically relevant conditions—is a cornerstone of modern electroanalysis. For drug development professionals, mastery of this tool enables the rational design of redox-active therapeutics, the development of sensitive analytical detection platforms, and a deeper understanding of biochemical redox processes. As electrochemical methods continue to gain prominence in life sciences, the principles outlined in this guide will remain fundamental to research innovation.

Predicting Reaction Spontaneity and Direction of Electron Flow

Within the field of standard reduction potential table electroanalysis research, the accurate prediction of a reaction's spontaneity and the subsequent direction of electron flow is a cornerstone capability. It is fundamental to advancing applications in drug development, materials science, and energy storage [17] [18]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the core principles, modern computational and experimental methods, and practical protocols for researchers. The continuous evolution of this field is marked by a transition from purely empirical table-based predictions to first-principles and machine-learning-enhanced models that offer greater accuracy and fundamental insight [17] [19] [18].

Core Principles: Standard Reduction Potentials

The spontaneity of a redox reaction is determined by its overall cell potential, ( E^\circ_{\text{cell}} ), which is derived from the standard reduction potentials of the involved half-reactions. The standard reduction potential, ( E^\circ ), is a measure of the inherent tendency of a chemical species to gain electrons and be reduced.

Calculating Cell Potential and Predicting Spontaneity

To construct a galvanic cell and predict spontaneity:

- Identify Half-Reactions: Determine the reduction and oxidation half-reactions.

- Consult Standard Tables: Find the standard reduction potentials (( E^\circ_{\text{red}} )) for both half-reactions.

- Determine the Cathode and Anode: The half-reaction with the more positive ( E^\circ{\text{red}} ) will undergo reduction (cathode). The half-reaction with the *less positive* (or more negative) ( E^\circ{\text{red}} ) will undergo oxidation (anode).

- Calculate ( E^\circ{\text{cell}} ): Use the formula: ( E^\circ{\text{cell}} = E^\circ{\text{cathode}} - E^\circ{\text{anode}} ) A positive ( E^\circ_{\text{cell}} ) indicates a spontaneous reaction [20].

Table: Standard Reduction Potentials at 25°C (Select Values) [20]

| Half-Reaction | ( E^\circ ) (V) |

|---|---|

| ( F_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2F^- ) | +2.87 |

| ( Au^{3+} + 3e^- \rightarrow Au ) | +1.50 |

| ( Cl_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2Cl^- ) | +1.36 |

| ( O2 + 4H^+ + 4e^- \rightarrow 2H2O ) | +1.23 |

| ( Br_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2Br^- ) | +1.07 |

| ( Ag^+ + e^- \rightarrow Ag ) | +0.80 |

| ( Fe^{3+} + e^- \rightarrow Fe^{2+} ) | +0.77 |

| ( I_2 + 2e^- \rightarrow 2I^- ) | +0.53 |

| ( O2 + 2H2O + 4e^- \rightarrow 4OH^- ) | +0.40 |

| ( Cu^{2+} + 2e^- \rightarrow Cu ) | +0.34 |

| ( 2H^+ + 2e^- \rightarrow H_2 ) | 0.00 (Reference) |

| ( Pb^{2+} + 2e^- \rightarrow Pb ) | -0.13 |

| ( Zn^{2+} + 2e^- \rightarrow Zn ) | -0.76 |

| ( Al^{3+} + 3e^- \rightarrow Al ) | -1.66 |

| ( Na^+ + e^- \rightarrow Na ) | -2.71 |

Advanced Considerations: The Impact of Complexation

The practical reduction potential of a metal ion is not fixed; it is highly dependent on its chemical environment. Coordination chemistry plays a critical role. For example, complexation can significantly stabilize a higher oxidation state, thereby lowering the reduction potential and making the ion less likely to be reduced [21].

Table: Effect of Complexation on Reduction Potential [21]

| Ion / Complex | ( E^\circ ) (V) | Context and Implication |

|---|---|---|

| ( Co^{3+} / Co^{2+} ) (Free Ions) | +1.853 V | Free ( Co^{3+} ) is a strong oxidizer. |

| ( [Co(NH3)6]^{3+} / [Co(NH3)6]^{2+} ) | +0.1 V | Complexation drastically stabilizes the +3 state, making it a much milder oxidizer. |

| ( Fe^{3+} / Fe^{2+} ) (Free Ions) | +0.771 V | -- |

| ( [Fe(CN)6]^{3-} / [Fe(CN)6]^{4-} ) | +0.36 V | The cyanide ligand stabilizes the +3 state, lowering the reduction potential. |

Modern Computational Prediction Methods

Moving beyond static table values, modern electroanalysis leverages computational models to predict reduction potentials and reaction outcomes with high accuracy, especially for novel molecules or complex environments.

First-Principles and Machine Learning Workflows

A cutting-edge approach integrates density functional theory (DFT) with machine learning (ML) to predict the practical reduction potential ((E_{red})) of electrolyte solvents, which is influenced by the electrode surface's reactivity [17].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental process for predicting practical reduction potentials:

Key Methodological Details:

- High-Throughput DFT Calculations: The process begins with DFT calculations on a diverse set of 12 common electrolyte solvents (e.g., carbonates, ethers) and 32 different active sites on a carbon anode surface, representing varying reactivity through metal-vacancy complexes [17].

- Generalized CHE Model: The practical reduction potential is calculated using a generalized computational hydrogen electrode model. The formula is derived from the Nernst equation and Faraday's law: ( E{red} = E{M}^{ \circleddash } - \frac{\Delta G{E}}{-nF} - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{a{red}}{a{ox}} ) where ( \Delta G{E} ) is the reaction free energy of the rate-limiting electrochemical elementary step, (n) is the number of electrons, (F) is Faraday's constant, and (E_{M}^{ \circleddash }) is the standard reduction potential of the metal element [17].

- Feature Engineering and ML Training: Properties of both the solvent molecules and the carbon surface active sites are used as features to train a machine learning model. Among several algorithms tested, the XGBoost model demonstrated the highest performance and was interpreted using SHAP analysis to identify impactful thermodynamic features [17].

Generative AI and Physical Constraint Enforcement

A significant challenge for purely data-driven models is adherence to physical laws. A novel generative AI approach, FlowER (Flow matching for Electron Redistribution), addresses this by explicitly conserving mass and electrons [18] [22].

The diagram below illustrates the core electron conservation principle of the FlowER model:

Key Methodological Details:

- Bond-Electron Matrix Representation: FlowER uses a bond-electron matrix, a method pioneered by Ivar Ugi in the 1970s, to represent the electrons in a reaction. This matrix uses nonzero values to represent bonds or lone electron pairs and zeros otherwise, providing a framework that naturally enforces conservation of both atoms and electrons [18] [22].

- Flow Matching Framework: The model is built on a modern deep generative framework called flow matching. It is trained on over a million chemical reactions from the U.S. Patent Office database. This allows it to learn the process of electron redistribution during a reaction, leading to highly reliable and interpretable predictions of reaction mechanisms [18] [22].

Table: Benchmarking of Computational Methods for Reduction Potential Prediction

| Method | Key Principle | Applicability / Strengths | Cited Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT/ML Workflow [17] | DFT calculates free energy; ML maps features to Ered. | Predicts practical Ered on reactive surfaces. Ideal for electrolyte design. | Requires known reduction mechanisms for training. |

| FlowER (Generative AI) [18] [22] | Flow matching on a bond-electron matrix. | Ensures mass/electron conservation; predicts mechanistic steps. | Limited coverage of metals and catalytic cycles in initial version. |

| OMol25 NNPs [7] | Neural network potentials trained on large quantum dataset. | Fast, general-purpose energy prediction across charge states. | Can be less accurate for main-group reduction potentials than DFT (B97-3c). |

| New Independent Atom Theory [19] | Uses independent atom approximation as a reference state. | More computationally affordable quantum method without sacrificing accuracy. | Emerging theory, scope of application still under investigation. |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation to confirm their accuracy and utility in real-world systems.

Protocol for Experimental Validation of Predicted Reduction Potentials

The following protocol is adapted from methods used to validate machine learning predictions of solvent reduction potentials in energy storage devices [17].

1. Objective: To experimentally determine the practical reduction potential ((E_{red})) of an electrolyte solvent on a specific electrode material (e.g., carbon anode) and compare it to computational predictions.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical Cell: A multi-electrode cell (e.g., 3-electrode setup: Working electrode, Counter electrode, Reference electrode).

- Electrode Materials: Electrodes matching the computational model (e.g., carbon-based anodes with defined surface properties).

- Electrolyte: Solution containing the solvent of interest and a supporting salt.

- Instrumentation: Potentiostat/Galvanostat for controlled electrochemical measurements.

- Environment: Inert atmosphere glovebox (e.g., Argon) to prevent water/oxygen contamination.

3. Procedure: 1. Cell Assembly: Inside an inert atmosphere glovebox, assemble the electrochemical cell with the prepared working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode. Introduce the prepared electrolyte solution. 2. Initial Characterization: Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) over a wide potential window to characterize the electrochemical stability of the system and identify any major reduction peaks. 3. Controlled Reduction Measurement: Use a technique like linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) or chronoamperometry at a slowly scanning rate (e.g., 0.1 mV/s) toward the reduction direction. The applied potential should be referenced to an appropriate standard (e.g., Li/Li+ or SHE). 4. Identify Onset Potential: The practical reduction potential ((E_{red})) is identified as the onset potential where the reduction current significantly increases above the background level. This onset signifies the beginning of the solvent's decomposition. 5. Post-Mortem Analysis: After the experiment, analyze the electrode surface using techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) or Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to confirm the formation of decomposition products and correlate the electrochemical signal with the physical formation of a solid electrolyte interphase (SEI).

4. Data Analysis and Validation:

- Compare the experimentally measured onset potential ((E_{red})) with the value predicted by the computational model (e.g., the ML workflow).

- Statistical analysis (e.g., calculation of mean absolute error, RMSE) across multiple solvents is used to validate the model's accuracy [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Electroanalysis Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Standard Reduction Potential Table | Foundational reference for estimating spontaneity and designing cell reactions [20]. |

| Computational Hydrogen Electrode (CHE) Model | A theoretical framework for calculating reaction free energies and predicting reduction potentials from first principles [17]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Software | Performs quantum mechanical calculations to determine electronic structures, energies, and properties of molecules and surfaces [17] [19]. |

| Bond-Electron Matrix | A representation of a molecule's electronic structure used in models like FlowER to enforce physical constraints and predict reaction mechanisms [18] [22]. |

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Instrument for applying controlled potentials/currents to electrochemical cells and measuring the response, essential for experimental validation [17]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine-learning models, such as those trained on the OMol25 dataset, used for fast and accurate prediction of molecular energies and properties [7]. |

The prediction of reaction spontaneity and electron flow is a dynamically advancing field. While standard reduction potential tables remain an indispensable starting point, the integration of computational chemistry, machine learning, and physically constrained generative AI represents the forefront of research. These methods, when coupled with robust experimental validation protocols, provide drug development professionals and scientists with powerful tools to design novel reactions, optimize electrolytes, and understand complex electrochemical systems with unprecedented accuracy and insight. The future of electroanalysis lies in the synergistic use of these multi-faceted approaches to navigate beyond empirical data towards predictive, first-principles understanding.

Calculating Standard Cell Potential with the Formula E°cell = E°cathode - E°anode

In the field of electroanalytical research, the accurate prediction of cell potential is fundamental for the development of advanced electrochemical systems, including biosensors and diagnostic devices. The standard cell potential, E°cell, provides a quantitative measure of the thermodynamic driving force behind electrochemical reactions, offering critical insights into reaction spontaneity and efficiency. This foundational principle, expressed by the equation E°cell = E°cathode - E°anode, serves as a cornerstone for researchers designing novel analytical platforms in pharmaceutical and diagnostic applications [23] [3] [24]. The precise calculation of this parameter enables scientists to screen viable redox pairs, optimize electrochemical cell configurations, and predict system behavior under standard conditions, thereby accelerating the development of robust analytical methodologies.

Fundamental Principles of Standard Potentials

Theoretical Framework

The standard cell potential arises from the difference in electrical potential between two electrodes in an electrochemical cell, fundamentally driven by the relative potential energy of valence electrons in different materials [23]. These potentials are measured under standard conditions—1 M concentration for solutions, 1 atm pressure for gases, and pure solids or liquids for other substances at 25°C—to enable consistent comparison across different electrochemical systems [23]. The standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) serves as the universal reference point with an assigned potential of 0 V, against which all other reduction potentials are measured [3]. This reference system consists of 1 atm hydrogen gas bubbled through a 1 M HCl solution with a platinum electrode, providing a stable baseline for electrochemical measurements [3].

Sign Conventions and Thermodynamic Implications

By convention, all tabulated standard electrode potentials (E°) are listed as reduction potentials, reflecting the tendency of a species to gain electrons [23] [3]. The calculated E°cell value provides direct insight into the thermodynamic favorability of the overall redox process: a positive E°cell indicates a spontaneous reaction (product-favored), while a negative value signifies a non-spontaneous reaction (reactant-favored) under standard conditions [24]. This relationship to Gibbs free energy (ΔG° = -nFE°cell) connects the electrochemical potential to the broader thermodynamic framework, enabling researchers to predict reaction outcomes and design systems with optimal energy profiles for analytical applications [25].

Methodology for Calculating Standard Cell Potential

Step-by-Step Calculation Protocol

The systematic determination of standard cell potential follows a rigorous analytical protocol to ensure accurate predictions of electrochemical behavior:

- Identify Half-Reactions: Determine both the reduction and oxidation half-reactions occurring in the electrochemical cell. Document the standard reduction potential (E°) for each half-reaction from authoritative reference tables [15] [26] [25].

- Determine Cathode and Anode: Identify the cathode as the electrode where reduction occurs (the half-reaction with the more positive or less negative E° value) and the anode as the electrode where oxidation occurs (the half-reaction with the less positive or more negative E° value) [24].

- Apply Calculation Formula: Calculate the standard cell potential using the fundamental equation E°cell = E°cathode - E°anode, where E°cathode is the standard reduction potential of the cathode half-reaction and E°anode is the standard reduction potential of the anode half-reaction [23] [3] [24].

- Interpret Thermodynamic Significance: A positive E°cell value confirms a spontaneous galvanic cell under standard conditions, while a negative value indicates the reverse reaction is spontaneous [24].

Practical Computational Example

Consider a galvanic cell consisting of Au³⁺/Au and Ni²⁺/Ni half-cells. The standard reduction potentials are:

Following the calculation protocol:

- The half-reaction with the more positive E° value (Au³⁺/Au) is reduction and occurs at the cathode.

- The half-reaction with the less positive E° value (Ni²⁺/Ni) is oxidation and occurs at the anode.

- Applying the formula: E°cell = E°cathode - E°anode = +1.52 V - (-0.25 V) = +1.77 V [24]

The positive E°cell value confirms a spontaneous galvanic cell, with gold ions acting as the oxidizing agent and nickel metal as the reducing agent.

Reference Data: Standard Reduction Potentials

The following comprehensive datasets provide standard reduction potentials essential for accurate E°cell calculations in electroanalytical research.

Table 1: Standard Reduction Potentials for Selected Half-Reactions (Acidic Solution) [15] [26] [25]

| Half-Reaction | E° (V) |

|---|---|

| F₂(g) + 2e⁻ → 2F⁻(aq) | +2.87 |

| Au³⁺(aq) + 3e⁻ → Au(s) | +1.52 |

| MnO₄⁻(aq) + 8H⁺(aq) + 5e⁻ → Mn²⁺(aq) + 4H₂O(l) | +1.51 |

| Cl₂(g) + 2e⁻ → 2Cl⁻(aq) | +1.36 |

| O₂(g) + 4H⁺(aq) + 4e⁻ → 2H₂O(l) | +1.23 |

| Br₂(aq) + 2e⁻ → 2Br⁻(aq) | +1.07 |

| Ag⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Ag(s) | +0.80 |

| Fe³⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Fe²⁺(aq) | +0.77 |

| I₂(s) + 2e⁻ → 2I⁻(aq) | +0.54 |

| Cu²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Cu(s) | +0.34 |

| 2H⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → H₂(g) | 0.00 |

| Pb²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Pb(s) | -0.13 |

| Ni²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Ni(s) | -0.25 |

| Cd²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Cd(s) | -0.40 |

| Fe²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Fe(s) | -0.44 |

| Zn²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Zn(s) | -0.76 |

| Mn²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Mn(s) | -1.18 |

| Al³⁺(aq) + 3e⁻ → Al(s) | -1.68 |

| Mg²⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ → Mg(s) | -2.36 |

| Na⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Na(s) | -2.71 |

| Li⁺(aq) + e⁻ → Li(s) | -3.04 |

Table 2: Experimentally Verified Cell Potentials for Common Galvanic Cells [24]

| Galvanic Cell | Calculated E°cell (V) | Measured E°cell (V) | Anode | Cathode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn/Cu | +1.10 | +1.08 | Zn | Cu |

| Ag/Zn | +1.56 | +1.53 | Zn | Ag |

| Zn/Pb | +0.64 | +0.61 | Zn | Pb |

| Ag/Pb | +0.92 | +0.92 | Pb | Ag |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Standard Cell Potential Measurement

The experimental determination of standard cell potential requires meticulous protocol implementation to ensure accurate and reproducible results:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish metal electrodes to a mirror finish using progressively finer abrasives (ending with 0.05 μm alumina slurry) to remove surface oxides and contaminants. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water before immersion in electrolyte solutions [24].

- Electrolyte Standardization: Prepare 1.0 M solutions of high-purity metal salts (e.g., ZnSO₄, CuSO₄, AgNO₃) using analytical grade reagents and deionized water (resistivity >18 MΩ·cm) to maintain standard state conditions [23] [24].

- Cell Assembly: Construct the electrochemical cell using appropriate vessel configuration, ensuring complete separation of half-cells while maintaining ionic connectivity via salt bridge (typically 3% agar in KNO₃ or KCl) [5] [27].

- Potential Measurement: Connect electrodes to a high-impedance voltmeter (>10 MΩ input impedance) using shielded cables to minimize current draw and measurement error. Record equilibrium potential after stabilization (±0.001 V over 60-second interval) [24].

- Data Validation: Compare experimental values against theoretical predictions, with discrepancies >5% triggering protocol re-evaluation and system troubleshooting [24].

Quality Control and Validation

Implement rigorous quality control measures including:

- Three-point calibration of measurement instrumentation using certified voltage references

- Replicate measurements (n≥3) to establish statistical significance

- Control experiments with known systems (e.g., Zn/Cu cell: theoretical 1.10 V) to validate methodology [24]

- Environmental monitoring (temperature stabilization at 25.0±0.5°C) to maintain standard conditions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Electroanalytical Studies [28] [26] [24]

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Metal Salts | ≥99.99% (AgNO₃, CuSO₄·5H₂O, ZnSO₄·7H₂O) | Source of electroactive species for standard solutions |

| Platinum Electrode | 99.95% Pt, polished mirror finish | Inert electrode for non-metallic redox systems |

| Salt Bridge Electrolyte | 3% Agar in KNO₃ (1M) or KCl (1M) | Ionic conduction between half-cells without reactant mixing |

| Deoxygenation System | N₂ or Ar gas with bubbling apparatus | Removal of dissolved oxygen to prevent interference |

| Buffer Solutions | pH 4.00, 7.00, 10.00 standards | Potential measurement in non-acidic media |

| High-Impedance Voltmeter | Input impedance >10 MΩ, ±0.1 mV accuracy | Accurate potential measurement without current draw |

Research Applications in Electroanalysis

Advanced Material Screening

The E°cell calculation framework provides an essential screening tool for identifying viable electrode materials in next-generation energy storage systems. For instance, research on Mn₂O³ as a high-electrode-potential cathode material (1.09 V vs. SCE in acidic media) demonstrates how standard potential assessments guide the development of aqueous rechargeable cells with operating voltages exceeding 2.0 V [28]. This methodology enables rapid evaluation of novel materials before committing to extensive synthesis and testing protocols.

Pharmaceutical Electroanalysis

In drug development, standard potential calculations facilitate the design of electrochemical biosensors for therapeutic monitoring. The thermodynamic parameters derived from E°cell values inform selection of appropriate redox mediators for amplifying detection signals in biological matrices. This approach enables real-time monitoring of pharmaceutical compounds and metabolic byproducts with enhanced sensitivity and specificity.

The rigorous application of the E°cell = E°cathode - E°anode formula provides an indispensable foundation for electroanalytical research across multiple disciplines. This systematic methodology enables researchers to make data-driven decisions in material selection, system design, and analytical development. As electrochemical applications continue to expand in pharmaceutical and diagnostic sciences, the precise calculation and interpretation of standard cell potentials remains a critical competency for advancing innovative research methodologies and technological breakthroughs.

The Absolute Standard Hydrogen Electrode Potential (ASHEP) is the fundamental reference point for the thermodynamic scale of oxidation-reduction potentials in electrochemistry [8]. It is defined as the chemical potential of electrons, referenced to the vacuum level, that equilibrates the redox reaction of hydrogen (½H₂ H⁺ + e⁻) under standard conditions (0.1 MPa for H₂ and 1 mol L⁻¹ for H⁺) [29]. While experimental electrochemistry typically uses the SHE as a relative reference set to 0 V, knowledge of its absolute potential value is essential for comparing redox potentials to the band edges of semiconductors or the chemical potential of electrons calculated in electronic structure calculations [29]. Establishing an accurate, non-empirical value for ASHEP has remained a significant challenge in theoretical electrochemistry, representing a major obstacle in establishing an absolute reference for electrode potential [30]. Recent advances combining first-principles calculations with machine learning (ML) techniques have enabled more precise predictions of ASHEP and other redox potentials across a wide range of systems [29] [30].

Theoretical Foundations

Definition and Significance of ASHEP

The Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) forms the basis of the thermodynamic scale of oxidation-reduction potentials, with its standard electrode potential (E°) declared to be zero volts at any temperature [8]. This convention allows all other electrode potentials to be measured relative to this reference point. However, the absolute electrode potential of SHE, which is referenced to the vacuum level, is estimated to be 4.44 ± 0.02 V at 25 °C based on the most reliable experimental recommendations by Trasatti and IUPAC [29] [8].

The distinction between relative and absolute potentials is crucial. The SHE consists of a platinized platinum electrode immersed in an acidic solution with unit activity of H⁺ ions, with pure hydrogen gas bubbled over its surface at 1 bar pressure [8]. The choice of platinum is due to its corrosion inertness, excellent catalytic activity for proton reduction, high exchange current density, and reproducible potential characteristics [8].

Thermodynamic Framework

The hydrogen electrode reaction is represented by the half-cell reaction:

2H⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ ⇌ H₂(g) [8]

The Nernst equation for the SHE is derived as:

[E = 0 - \frac{RT}{2F}\ln\frac{p{\mathrm{H2}}/p^0}{a_{\mathrm{H^+}}^2}]

Which can be simplified to the practical form:

[E = -0.0591\left(\mathrm{pH} + \frac{1}{2}\log p{\mathrm{H2}}\right)]

Under standard conditions where (p{\mathrm{H2}} = 1) bar and pH = 0, this simplifies further to E = 0 V, consistent with the conventional assignment [8].

The absolute potential is directly related to the real potential of the proton (also referred to as the work function of a proton), which includes the contribution of the electrostatic potential difference across the vacuum-solute interface [29]. This real potential is further related to the solvation free energy, though separating the surface potential contribution from the real potential has been a topic of long-standing debate in the field [29].

Table 1: Experimental Values for Absolute Standard Hydrogen Electrode Potential

| Value (V) | Method | Reference/Year | Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| -4.44 | IUPAC Recommended | Trasatti / IUPAC [29] [8] | ± 0.02 V |

| -4.2 | Ion-Electron Recombination | PMC (2008) [31] | ± 0.4 V |

| -4.43 | Work Function & Schottky Barrier | Reiss & Heller [31] | Not specified |

| -4.73 | Work Function Measurement | Gomer & Tryson [31] | Not specified |

Computational Challenges and Historical Approaches

Fundamental Challenges in ASHEP Prediction

Predicting ASHEP from first principles has proven extremely challenging due to several fundamental difficulties:

Free Energy Calculations: The redox potential Uredox is determined by the free energy difference ΔA between reduced and oxidized states: (U{\text{redox}} = -\Delta A/ne) [29]. Calculating this free energy difference precisely requires thermodynamic integration (TI) methods that are computationally demanding [29].

Sampling Difficulties: Reactions involving significant structural changes, such as the hydrogen redox reaction with solvation and proton diffusion, require extensive sampling over many timesteps to achieve statistical accuracy [29].

Periodic Boundary Conditions: ASHEP is measured relative to the vacuum level, a quantity not directly accessible in simulations using periodic boundary conditions [29].

Computational Cost: Accurate calculation of redox potentials often requires computationally intensive non-local hybrid functionals that would necessitate hundreds of millions of core hours with complete plane-wave basis sets [29].

Previous Computational Strategies

Prior approaches to addressing these challenges have included various approximations:

- Restraining Potentials: Sprik and coworkers introduced restraining potentials that fix protons to specific water molecules during short (5-20 ps) first-principles molecular dynamics (FPMD) simulations to achieve stable results through TI calculations [29].

- Continuum Solvation Models: Many calculations employed continuum solvation models to approximate solvent effects [29].

- Localized Basis Sets: Some approaches used localized Gaussian basis sets and norm-conserving pseudopotentials, though these can introduce basis set superposition errors [29].

- Cluster-Pair Based Approach: Methods based on cluster-ion solvation data have been used, though results have shown significant variation from -4.80 to -4.28 V [29].

These different approximations with varying empirical parameters have yielded scattered results in the range of -4.56 to -4.18 V, highlighting the need for more robust, non-empirical approaches [29].

Recent Advances: Machine Learning-Aided First Principles Calculations

Hybrid Functional Approach

A significant breakthrough in predicting ASHEP has been achieved through a framework combining hybrid functionals with machine learning acceleration [29] [30]. Jinnouchi et al. demonstrated that a hybrid functional incorporating 25% exact exchange (PBE0+D3) enables quantitative predictions when statistically accurate phase-space sampling is achieved [29]. This approach predicts the ASHEP as -4.52 ± 0.09 V and the real potential of the proton as -11.12 ± 0.09 eV, values remarkably close to the IUPAC recommended values of -4.44 ± 0.02 V and -11.28 ± 0.02 eV [29].

The methodology extends machine learning-aided thermodynamic integration, previously developed for electron insertion into aqueous solutions, to also allow for proton insertion into aqueous solutions [29]. This extension was crucial for addressing the ASHEP prediction challenge.

Methodological Framework

The computational framework involves several key components:

Thermodynamic Integration: The free energy change is precisely determined by thermodynamic integration, seamlessly connecting the proton in the vacuum to the interacting proton in the aqueous phase [29].

Machine-Learned Force Fields: ML force fields enable highly accurate statistical averaging at a fraction of the computational cost of full first-principles calculations [29].

Δ-Machine Learning: This approach corrects errors in ML force fields through thermodynamic perturbation theory calculations [29] [32].

Hybrid Functional: The PBE0 functional with 25% exact exchange, combined with dispersion corrections (PBE0+D3), provides the appropriate level of electronic structure theory [29].

To facilitate the free energy calculation, the hydrogen oxidation reaction is divided into three steps: dissociation (H₂(g) → 2H(g)), ionization (2H(g) → 2H⁺ + 2e⁻(g)), and solvation (2H⁺(g) → 2H⁺(aq)) [29]. The corresponding free energy changes are ΔₐₜG⁰ for dissociation, 2ΔᵢₒₙG⁰ for ionization, and α for solvation [29].

Validation and Applications

The ML-aided first-principles method has been validated across seven redox couples, including molecules and transition metal ions (Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺/Cu⁺, Ag²⁺/Ag⁺, V³⁺/V²⁺, Ru³⁺/Ru²⁺, and O₂/O₂⁻) [29]. This demonstrates that the hybrid functional can predict redox potentials across a wide range of potentials with an average error of 140 mV (80 mV in the arXiv version) [29] [32]. The application to the oxygen reduction reaction in polymer electrolyte fuel cells elucidated a mechanism for enhancing catalytic activity, demonstrating that attaching organic molecules to Pt catalysts disrupts the hydrogen-bonding network near the electrode, leading to improved performance [30].

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Methods for ASHEP Prediction

| Method | ASHEP Value (V) | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML-aided First Principles [29] | -4.52 ± 0.09 | PBE0+D3 functional; 25% exact exchange; MLFF acceleration; Thermodynamic integration | Still computationally demanding; Requires expertise in ML methods |

| Restraining Potential Approach [29] | -4.56 | Localized basis sets; Norm-conserving pseudopotentials; Restraining potentials | Basis set superposition errors; Restraints may affect proton entropy |

| Continuum Solvation Models [29] | -4.56 to -4.18 | Computational efficiency; Simplified solvent treatment | Limited accuracy for explicit solvent effects |

| Gas-Phase Nanodrop Calorimetry [31] | -4.2 ± 0.4 | Experimental measurement; Includes solvent effects past two solvent shells | Large uncertainty; Requires Born theory estimates |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

First-Principles Calculation with ML Acceleration

The protocol for determining ASHEP using machine learning-aided first-principles calculations involves these critical steps:

System Preparation: Construct simulation cells containing water molecules and protons, ensuring appropriate periodic boundary conditions [29].

Training Data Generation: Perform first-principles molecular dynamics simulations using hybrid density functional theory to generate reference data for training machine learning force fields [29].

MLFF Training: Train machine learning force fields on the ab initio data to create accurate surrogate models that can rapidly sample phase space [29].

Thermodynamic Integration: Use the MLFF to perform extensive sampling along the coupling parameter λ that connects the non-interacting proton in the gas phase to the interacting proton in the aqueous phase, calculating the integral (\alpha = \int0^1 d\lambda \langle \partial U(\lambda)/\partial \lambda \rangle\lambda) [29].

Δ-ML Correction: Apply Δ-machine learning to correct any residual errors in the MLFF predictions, using thermodynamic perturbation theory [29].

Free Energy Calculation: Compute the dissociation free energy ΔₐₜG⁰ using ideal gas models and ionization free energy ΔᵢₒₙG⁰ using single-point first-principles calculations [29].

ASHEP Determination: Combine the calculated free energies according to the equation: (U{\text{abs}} = [\Delta{\text{at}}G^0 + 2\Delta_{\text{ion}}G^0 + 2\alpha]/2F) to obtain the absolute potential [29].

Gas-Phase Nanodrop Calorimetry

An alternative experimental approach for establishing an absolute electrochemical scale uses gas-phase nanodrop calorimetry [31]:

Ion Preparation: Generate hydrated ions containing individual redox-active centers (e.g., [M(NH₃)₆]³⁺, M = Ru, Co, Os, Cr, Ir, and Cu²⁺ ions) using electrospray ionization [31].

Electron Capture: Introduce thermally generated electrons for capture by multivalent hydrated ions in the gas phase [31].

Energy Measurement: Measure water molecule loss from reduced precursors - the dissociation process is statistical for large hydrated clusters, allowing energy deposition from electron capture to be obtained from the sum of water binding energies lost [31].