Redox Titration vs. Potentiometric Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of redox titration and potentiometric methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Redox Titration vs. Potentiometric Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of redox titration and potentiometric methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the fundamental principles of electrochemical reactions and the Nernst equation, delves into specific methodological applications for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and excipients as per pharmacopeia standards, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios in complex matrices, and offers a direct validation framework for selecting the optimal analytical technique. The scope is designed to equip scientists with the knowledge to enhance accuracy, efficiency, and compliance in pharmaceutical analysis.

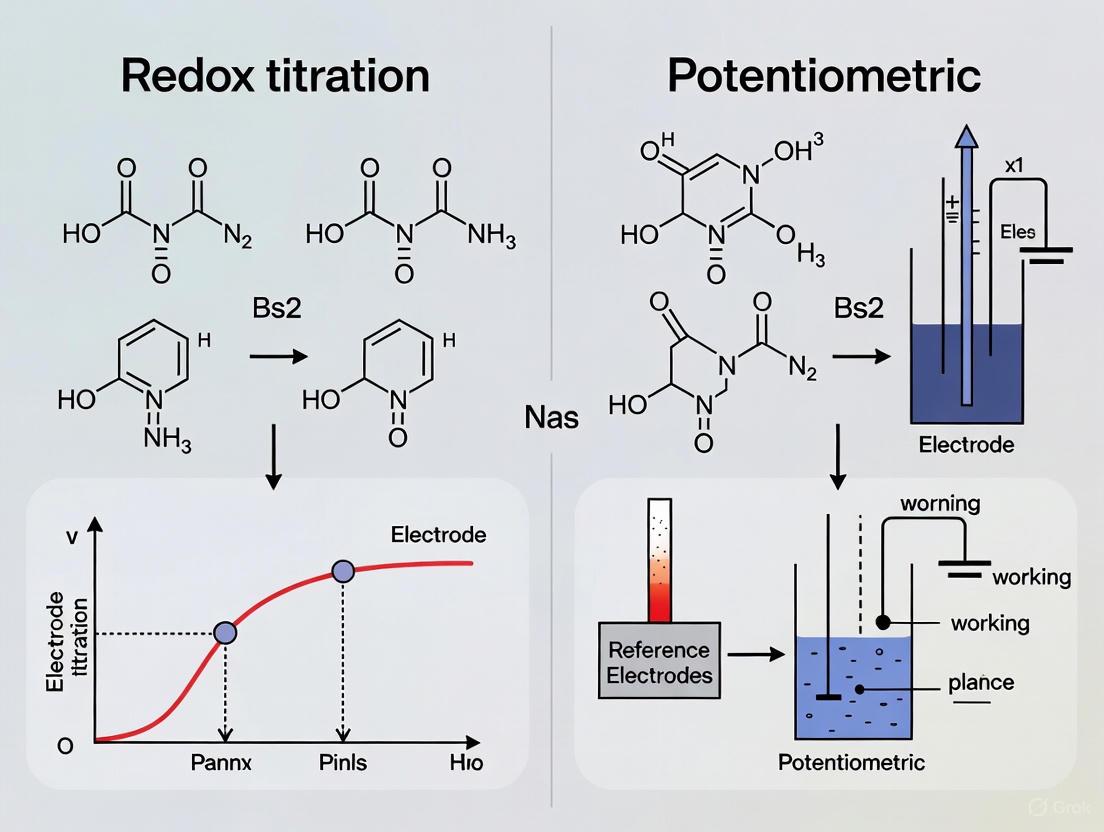

Core Principles: Understanding Electrochemical Foundations and Titration Curves

Redox titration is a volumetric analytical technique based on oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions between the analyte and a standard titrant. These reactions involve the transfer of electrons from a reducing agent to an oxidizing agent, enabling the quantitative determination of various analytes. Potentiometric titration represents a refined approach to redox titration that utilizes potential measurements to identify the endpoint objectively, eliminating the subjectivity of visual indicators. Within pharmaceutical research and development, these methods provide critical tools for drug substance quantification, excipient analysis, and quality control testing of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). The evolution from visual to potentiometric endpoint detection has significantly enhanced the accuracy, precision, and applicability of titration methods in analytical laboratories, with modern pharmacopeias now officially accepting automated titration procedures [1] [2].

Fundamental Principles: Electron Transfer and Measurement

Core Concepts in Redox Chemistry

Oxidation-reduction reactions involve complementary processes where one species loses electrons while another gains them. Oxidation is defined as the loss of electrons, resulting in an increase in oxidation state, while reduction involves the gain of electrons, decreasing the oxidation state. The species that causes oxidation by accepting electrons is termed the oxidizing agent (oxidant), and the species that causes reduction by donating electrons is the reducing agent (reductant). These electron transfer processes form the fundamental basis for all redox titrations [1].

The tendency of a species to gain or lose electrons is quantified by its electrode potential, with the overall driving force for a redox reaction being the difference in potential between the participating half-reactions. The Nernst equation mathematically describes the relationship between electrode potential and concentration of electroactive species:

E = E⁰ - (RT/nF) ln(Q)

where E represents the electrode potential under non-standard conditions, E⁰ is the standard electrode potential, R is the ideal gas constant, T is absolute temperature, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is the Faraday constant, and Q is the reaction quotient. At 25°C, this simplifies to:

E = E⁰ - (0.05916/n) log([products]/[reactants]) [1]

This equation is fundamental to potentiometric measurements, as it enables the determination of analyte concentrations from measured potential values.

Comparative Analysis: Redox Titration vs. Potentiometric Methods

Methodological Distinctions and Applications

| Feature | Classical Redox Titration | Potentiometric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Endpoint Detection | Visual indicators (color change) | Potential measurement via electrode system |

| Primary Instrumentation | Burette, visual assessment | Electrodes, potentiometer, automated buret |

| Key Components | Titrant, indicator, analyte | Indicator electrode, reference electrode, titrant, analyte |

| Quantification Basis | Volume at visual color change | Volume at potential inflection point |

| Sensitivity | Limited by visual detection | Can detect below 10⁻⁶ M concentrations [3] |

| Objective Precision | Subject to analyst interpretation | Highly objective and reproducible |

| Applicable Solutions | Clear, colorless ideal | Colored, turbid, and complex matrices |

| Automation Potential | Manual execution | Fully automatable systems |

| Data Acquisition | Single endpoint | Continuous potential-volume data points |

| Reference Electrode | Not applicable | Essential (e.g., Ag/AgCl, SCE) [1] |

| Indicator Electrode | Not applicable | Critical (e.g., Pt, Au, ion-selective) [1] |

Advantages and Limitations in Pharmaceutical Settings

Potentiometric titration offers significant advantages for pharmaceutical analysis, particularly in regulated environments. The transition from manual to automated titration improves accuracy, precision, and efficiency while reducing human influence on analytical results [2]. Modern automated titration systems consist of four key components: an automatic piston buret for precise titrant delivery, a sample homogenization system, an endpoint detection electrode that removes subjectivity, and automated result calculation and display [2].

The sensitivity of potentiometric methods has been demonstrated in research settings, with detection limits reaching approximately 2 meq/kg for hydroperoxide determination in degraded polypropylene—significantly superior to conventional UV and manual titration methods [4]. This enhanced sensitivity enables applications in challenging matrices and trace analysis scenarios common in pharmaceutical development.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fundamental Redox Titration Procedure

Principle: This protocol outlines the determination of an analyte using a standardized redox titrant with visual endpoint detection. The procedure is based on the quantitative electron transfer between the titrant and analyte.

Materials:

- Standardized redox titrant (e.g., KMnO₄, K₂Cr₂O₇, I₂, or Na₂S₂O₃)

- Appropriate visual indicator (e.g., starch, ferroin, diphenylamine sulfonate)

- Analytical balance, volumetric flasks, burette, and Erlenmeyer flasks

- Sample solution containing the analyte of interest

Procedure:

- Standardization: Pre-standardize the titrant against a primary standard if necessary (e.g., potassium dichromate for sodium thiosulfate).

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh and transfer the sample to a titration vessel, dissolving in appropriate solvent.

- Condition Setting: Adjust solution conditions (pH, ionic strength) as required for the specific redox reaction.

- Indicator Addition: Add the appropriate visual indicator to the sample solution.

- Titration: Slowly add the titrant from the burette with continuous swirling.

- Endpoint Determination: Record the titrant volume at the first permanent color change indicative of the equivalence point.

- Calculation: Determine the analyte concentration using reaction stoichiometry and titrant volume [1] [5].

Advanced Potentiometric Titration Protocol

Principle: This method employs potential measurements to objectively identify the titration endpoint, particularly suited for colored, turbid, or complex samples where visual indicators are ineffective.

Materials:

- Potentiometric titrator or manual setup with potentiometer

- Appropriate electrode pair (indicator and reference electrode, or combined electrode)

- Standardized titrant solution

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars

Procedure:

- System Setup: Install and calibrate the appropriate electrode system based on the titration type.

- Electrode Selection: Choose indicator electrode based on the reaction:

- Pt electrode for redox titrations (e.g., antibiotic assays, peroxide value)

- Ag electrode for precipitation titrations (e.g., chloride, iodide determination)

- Ion-selective electrode for complexometric titrations (e.g., calcium with EDTA) [2]

- Solution Preparation: Transfer the analyte solution to the titration vessel and immerse the electrodes.

- Data Collection: Begin titration with continuous recording of potential (E) versus titrant volume (V).

- Endpoint Determination: Identify the equivalence point using:

- First Derivative Plot (ΔE/ΔV vs. Vavg): Peak maximum indicates equivalence point

- Second Derivative Plot (Δ²E/ΔV² vs. Vavg): Zero crossing indicates equivalence point

- Result Calculation: Automatically compute analyte concentration from equivalence point volume [1].

Figure 1: Potentiometric Titration Workflow. This diagram illustrates the systematic procedure for performing potentiometric titrations, from electrode setup through final calculation.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Critical Reagents and Materials for Redox and Potentiometric Methods

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | Strong oxidizing titrant, self-indicating | Redox titrations in acidic medium |

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Primary standard oxidizing agent | Standardization of reducing titrants |

| Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) | Reducing titrant for iodine | Iodometric analyses, peroxide value |

| Iodine (I₂) | Moderate oxidizing titrant | Direct iodimetry, API assays |

| Platinum Electrode | Redox indicator electrode | Potentiometric redox titrations |

| Reference Electrodes | Stable potential reference (Ag/AgCl, SCE) | All potentiometric measurements |

| Ferroin Indicator | Redox indicator (color change at ~1.14 V) | Visual redox endpoint detection |

| Starch Solution | Specific indicator for iodine | Visual detection in iodometry |

| Ion-Selective Electrodes | Selective ion detection | Specific cation/anion determination |

Data Interpretation and Analytical Validation

Titration Curve Analysis and Equivalence Point Determination

Redox titration curves plot the electrochemical potential (y-axis) against the volume of titrant added (x-axis), typically producing a sigmoidal curve with a steep potential jump at the equivalence point. The region before the equivalence point is dominated by the redox couple of the analyte, while the region after the equivalence point is controlled by the redox couple of the titrant. At the equivalence point, neither the analyte nor titrant is in significant excess, and the potential can be calculated based on the standard potentials of both half-reactions [1].

For potentiometric titrations, the equivalence point is mathematically determined from the inflection point of the sigmoidal curve. The first derivative plot (ΔE/ΔV vs. Vavg) peaks at the equivalence point, while the second derivative plot (Δ²E/ΔV² vs. Vavg) crosses zero at this critical point. These mathematical approaches provide objective and precise equivalence point detection, eliminating the subjective judgment associated with visual color changes [1].

Method Validation in Pharmaceutical Context

For pharmaceutical applications, validation of titration methods follows regulatory guidelines such as USP General Chapter <1225>. Key validation parameters include accuracy, precision, specificity, linearity, range, detection limit, quantitation limit, and robustness. Automated titration systems significantly enhance method validation capabilities through improved data integrity, traceability, and reduced analyst variability [2]. Compliance with electronic records requirements (e.g., 21 CFR Part 11) is essential for pharmaceutical implementation, with modern titration software providing the necessary security, audit trails, and data protection features.

The selection between classical redox titration and modern potentiometric approaches depends on multiple factors including required precision, sample matrix, available instrumentation, and regulatory considerations. While visual redox titration remains valuable for routine analyses with clear endpoints, potentiometric methods offer superior objectivity, sensitivity, and applicability to challenging matrices. The demonstrated ability of potentiometric titration to achieve detection limits below 10⁻⁶ M, coupled with its compatibility with automated systems, positions it as the preferred technique for pharmaceutical research and quality control [3] [2].

The continued evolution of titration methodology, including the development of digital electrodes with integrated data storage and advanced detection systems, further enhances the capabilities of electrochemical analysis for drug development professionals. By understanding the fundamental principles, comparative advantages, and practical implementation details of both approaches, researchers can make informed decisions to optimize analytical workflows in pharmaceutical settings.

Potentiometry is an electroanalytical technique in which the potential (electromotive force) of an electrochemical cell is measured under static conditions where little to no current flows through the sample [6] [7]. This fundamental principle distinguishes potentiometry from other electrochemical methods and forms the basis for its application across various scientific domains, including clinical diagnostics, pharmaceutical analysis, and environmental monitoring [8] [9] [10]. In a typical potentiometric measurement, an indicator electrode responds to changes in the activity (effective concentration) of the analyte, while a reference electrode provides a stable, known potential against which changes can be measured [6] [9]. The measured potential is proportional to the logarithm of the analyte's activity, as described by the Nernst equation, allowing for quantitative determinations [1] [9].

The instrumentation required for potentiometry is notably straightforward, consisting primarily of an indicator electrode, a reference electrode, and a potential measuring device [6]. This simplicity contributes to the technique's relatively low cost compared to other analytical methods such as atomic spectroscopy or ion chromatography [6]. Additionally, because potentiometric measurements cause minimal perturbation to the sample and are not affected by color or turbidity, they are particularly valuable for analyzing complex matrices like blood, urine, and environmental samples [6] [8].

Fundamental Principles: The Nernst Equation and Zero-Current Condition

The theoretical foundation of potentiometry rests upon the Nernst equation, which relates the potential of an electrochemical cell to the activities of the electroactive species involved [1] [9]. For a general half-reaction written as a reduction: [ aA + bB + ne^- \rightleftharpoons cC + dD ] The Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{[C]^c[D]^d}{[A]^a[B]^b} ] where E is the electrode potential under non-standard conditions, E⁰ is the standard electrode potential, R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹), T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin, n is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction, F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹), and the terms in square brackets represent the activities of the species involved [1]. At 25°C (298.15 K), the equation can be simplified using base-10 logarithms: [ E = E^0 - \frac{0.05916}{n} \log \frac{[products]}{[reactants]} ] for reduction reactions [1].

The "zero-current condition" is a critical aspect of potentiometric measurements that ensures the composition of the electrochemical cell remains unchanged during analysis [7]. Unlike voltammetric or amperometric techniques where current flows as a result of an applied potential, potentiometry measures the potential that naturally develops at the electrode-solution interface when no significant current passes between the electrodes [10]. This equilibrium measurement provides significant advantages, including minimal sample perturbation, reduced susceptibility to interferent effects, and avoidance of ohmic drop problems associated with current flow [10].

Instrumentation and Electrode Systems

Reference Electrodes

The reference electrode maintains a constant, known potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured [1] [9]. To serve this function effectively, reference electrodes must exhibit stable potential over time, reproducibility, and minimal temperature dependence [1].

Table 1: Common Reference Electrodes in Potentiometry

| Electrode Type | Half-Reaction | Potential vs. SHE (25°C) | Applications and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) | 2H⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ ⇌ H₂(g) | 0.000 V (by definition) | Primary standard; impractical for routine use due to need for H₂ gas [1] |

| Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) | Hg₂Cl₂(s) + 2e⁻ ⇌ 2Hg(l) + 2Cl⁻(aq) | +0.241 V | Widely used; contains mercury (toxic); potential depends on Cl⁻ concentration [1] |

| Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) | AgCl(s) + e⁻ ⇌ Ag°(s) + Cl⁻ | +0.197 V (for saturated KCl) | Common in clinical applications; often used as internal reference in ISEs [9] |

Indicator Electrodes

Indicator electrodes respond to changes in the activity of the target analyte [6]. Their potential varies with the concentration of the species of interest, following the Nernst equation [9].

Table 2: Types of Potentiometric Indicator Electrodes

| Electrode Type | Principle | Key Applications | Selectivity Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) | Membrane-based potential development | pH, Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Li⁺, Cl⁻ [6] [9] | High selectivity achieved through membrane composition [6] |

| Redox Electrodes | Electron transfer reactions | Redox titrations [1] | Response depends on standard potential of redox couple [9] |

| Glass Membrane Electrodes | Ion exchange at glass surface | pH, Na⁺ [9] | Special glass formulations provide selectivity [9] |

| Polymer Membrane Electrodes | Ionophores in PVC matrix | K⁺, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, pharmaceuticals [9] [10] | Selectivity determined by ionophore structure [9] |

Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs)

Ion-selective electrodes represent the most important class of indicator electrodes in modern potentiometry due to their high selectivity for specific ions [6]. The potential developed across an ISE membrane (EMEM) can be expressed as: [ E{MEM} = E^0 + \frac{0.0592}{n} \log a_1 ] where a₁ is the activity of the ion of interest in the external sample solution [9]. The constant E⁰ incorporates the potential of the internal reference electrode, the liquid junction potential, and the fixed activity of the ion in the internal solution [9].

ISEs are classified based on their membrane composition and mechanism of operation. Glass membrane electrodes, primarily used for pH and sodium ion measurements, employ specially formulated glass compositions that determine their selectivity [9]. Polymer membrane electrodes incorporate ionophores (ion-recognition molecules) in a plasticized PVC matrix that selectively complex with target ions [9]. Solid-contact ISEs represent an advancement that eliminates the internal solution, improving mechanical stability and facilitating miniaturization [10].

Diagram 1: Working principle of a potentiometric ion-selective electrode (ISE) showing the complete electrochemical cell with zero-current measurement.

Potentiometric Methods Versus Redox Titration: A Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Differences in Approach

While both potentiometric methods and redox titrations utilize electrochemical principles, they represent fundamentally different approaches to chemical analysis. Redox titrations are volumetric methods based on oxidation-reduction reactions between the analyte and a standard titrant, where the endpoint is determined by a sharp change in potential measured potentiometrically or through color-changing indicators [1] [11]. In contrast, direct potentiometry measures the equilibrium potential of an electrochemical cell to determine analyte activity without reagent consumption or chemical transformation of the analyte [6] [7].

Comparison of Performance Characteristics

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Redox Titration and Potentiometric Methods

| Parameter | Redox Titration | Direct Potentiometry |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Monitoring potential change during titrant addition [1] | Direct potential measurement at zero current [6] [7] |

| Measurement Type | Dynamic process monitoring | Equilibrium measurement |

| Endpoint Detection | Inflection point in sigmoidal curve [1] | Direct reading from calibration curve |

| Precision | High (0.1-1%) [11] | Moderate to high (1-3%) |

| Accuracy | Dependent on titrant standardization and indicator selection [11] | Dependent on calibration and electrode stability |

| Sensitivity | Millimolar range | Micromolar to nanomolar for some ISEs [10] |

| Selectivity | Dependent on redox potential differences | Determined by membrane selectivity [9] |

| Sample Consumption | Moderate to high (mL range) | Low (μL to mL) |

| Analysis Time | Minutes to tens of minutes | Seconds to minutes [10] |

| Automation Potential | High with automated burettes [11] | High, suitable for continuous monitoring [10] |

| Cost Considerations | Moderate (burettes, titrants) | Low to moderate (electrode costs) [6] |

Endpoint Detection in Titrimetry

In potentiometric redox titrations, the endpoint is determined by identifying the point of maximum slope on the potential versus titrant volume curve [1]. This can be accomplished through mathematical treatment of the data:

- First Derivative Plot: The change in potential with respect to the change in titrant volume (ΔE/ΔV) is plotted against the average titrant volume. The peak maximum corresponds to the equivalence point [1].

- Second Derivative Plot: The second derivative (Δ²E/ΔV²) is plotted against volume. The point where this plot crosses zero (changing from positive to negative) indicates the equivalence point [1].

This mathematical approach to endpoint detection provides significant advantages over visual indicators, including objectivity, applicability to colored or turbid solutions, and suitability for automation [1] [11].

Diagram 2: Workflow of a potentiometric redox titration showing the sequence from electrode setup to equivalence point determination.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Direct Potentiometric Measurement

Objective: Determination of ion concentration (e.g., K⁺) in aqueous solution using an ion-selective electrode.

Materials and Equipment:

- Ion-selective electrode (K⁺-ISE)

- Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl)

- Potentiometer or pH/mV meter

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars

- Standard solutions for calibration (e.g., 10⁻¹ M, 10⁻² M, 10⁻³ M, 10⁻⁴ M KCl)

- Sample solutions of unknown concentration

- Temperature control bath (optional, for high-precision work)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Condition the ISE in a solution of intermediate concentration (e.g., 10⁻² M KCl) for 30 minutes prior to first use. For subsequent uses, rinse thoroughly with deionized water and blot dry with laboratory tissue.

- Calibration Curve:

- Immerse the ISE and reference electrode in the lowest concentration standard.

- Measure the potential after stabilization (typically 1-3 minutes).

- Repeat with increasing standard concentrations, measuring potential for each.

- Plot potential (mV) versus log₁₀[K⁺] to obtain calibration curve.

- Sample Measurement:

- Rinse electrodes with deionized water between measurements.

- Immerse electrodes in sample solution.

- Measure potential after stabilization.

- Determine concentration from calibration curve.

- Validation: Check electrode response with a standard solution after sample measurements to verify no drift has occurred.

Data Analysis: The potential should follow the Nernstian relationship: [ E = E^0 + \frac{0.05916}{1} \log [K^+] ] A slope of 59.16 mV per decade concentration change indicates ideal Nernstian behavior for a monovalent ion at 25°C [9].

Protocol for Potentiometric Redox Titration

Objective: Determination of iron(II) concentration by titration with cerium(IV).

Materials and Equipment:

- Platinum indicator electrode

- Reference electrode (e.g., SCE or Ag/AgCl)

- Burette or automated titrator

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bar

- Cerium(IV) sulfate titrant (standardized, ~0.1 M)

- Sample solution containing unknown Fe²⁺ concentration

- Sulfuric acid (1 M) for pH adjustment

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation:

- Transfer 25.00 mL of unknown Fe²⁺ solution to titration vessel.

- Add 25 mL 1 M H₂SO₄ to provide appropriate acidic medium.

- Add deionized water to bring total volume to approximately 100 mL.

- Electrode Setup:

- Immerse platinum indicator electrode and reference electrode in solution.

- Connect electrodes to potentiometer.

- Titration:

- Begin stirring at constant rate.

- Record initial potential.

- Add titrant in small increments (0.5-1.0 mL), recording potential after each addition.

- Near the equivalence point (indicated by larger potential changes), decrease increment size to 0.1-0.2 mL.

- Continue titration until well past equivalence point (approximately 1.5 times the expected equivalence volume).

- Endpoint Determination:

- Plot potential (E) versus volume (V) of titrant added.

- Calculate first derivative (ΔE/ΔV) and second derivative (Δ²E/ΔV²).

- Identify equivalence point from the maximum in the first derivative plot or zero-crossing in the second derivative plot.

Data Analysis: The equivalence point volume is used to calculate the Fe²⁺ concentration: [ C{Fe^{2+}} = \frac{C{Ce^{4+}} \times V{eq}}{V{sample}} ] where C is concentration and V is volume [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Potentiometric Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrodes | Direct potentiometric measurement | pH glass electrode, valinomycin-based K⁺-ISE, Ca²⁺-ISE with ETH 1001 ionophore | Selectivity coefficients should be checked regularly; requires proper conditioning [6] [9] |

| Reference Electrodes | Stable potential reference | Ag/AgCl with KCl electrolyte, double-junction reference electrodes | Electrolyte concentration affects potential; requires periodic refilling [1] [9] |

| Redox Indicators | Visual endpoint detection in redox titrations | Ferroin (E° = 1.14 V), Diphenylamine sulfonate | Must have standard potential between analyte and titrant potentials [1] |

| Titrants for Redox Titrations | Oxidizing/reducing agents for titrimetry | KMnO₄, K₂Cr₂O₇, Ce(SO₄)₂, Na₂S₂O₃ | Require standardization; stability varies (KMnO₄ not primary standard) [1] |

| Ionic Strength Adjusters | Constant background ionic strength | Ionic strength adjustment buffers (ISA) | Critical for direct potentiometry to fix activity coefficients [9] |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Provide conductivity in non-aqueous media | Tetraalkylammonium salts, lithium perchlorate | Electrochemically inert over potential window of interest |

| Solid-Contact Materials | Ion-to-electron transduction in solid-contact ISEs | Conducting polymers (PEDOT), carbon nanomaterials, nanocomposites | High capacitance materials reduce potential drift [10] |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

Clinical and Pharmaceutical Applications

Potentiometric methods have found extensive application in clinical chemistry and pharmaceutical analysis due to their ability to measure ions and drug molecules directly in complex biological matrices [8] [9]. In clinical laboratories, ISEs are routinely used for measuring electrolytes (Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻, Ca²⁺, Li⁺) in blood serum and urine [9]. Abnormalities in electrolyte balance are frequent in hospitalized patients and associated with higher mortality and morbidity, making reliable monitoring crucially important [10]. For pharmaceutical analysis, potentiometric sensors have been developed for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), particularly for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices or high inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability [10]. These sensors enable direct measurement of drug concentrations in biofluids without extensive sample preparation, offering advantages for point-of-care testing [8].

Environmental Monitoring

Environmental monitoring represents another significant application area for potentiometric sensors, particularly for determining heavy metals (copper, iron, lead, mercury) in soil and water samples [10]. Additionally, potentiometric sensors have been developed for monitoring nitrate, ammonium, and chloride ions, which impact human health and agricultural practices through effects on eutrophication, soil salinity, and water quality [10]. The ability of ISEs to provide continuous monitoring with minimal sample perturbation makes them valuable tools for environmental assessment.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Recent advancements in potentiometric sensors include the development of 3D-printed electrodes, paper-based analytical devices, and wearable sensors for continuous monitoring [10]. Three-dimensional printing offers improved flexibility and precision in manufacturing ISEs, while rapid prototyping decreases optimization time [10]. Paper-based sensors provide cost-effective platforms for point-of-care analysis, permitting rapid determination of various analytes in field settings [10]. Wearable potentiometric sensors represent one of the most promising developments, allowing continuous monitoring of biomarkers, electrolytes, and pharmaceuticals in biological fluids [10]. These devices typically incorporate solid-contact ISEs with high-capacitance transduction layers to ensure signal stability during movement and extended use [10].

Nanocomposite materials have shown particular promise as transducers in solid-contact ISEs, with synergistic effects enhancing sensing performance [10]. For instance, MoS₂ nanoflowers filled with Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles have been used to stabilize structure and increase capacitance, while tubular gold nanoparticles with tetrathiafulvalene (Au-TTF) have demonstrated high capacitance and stability for potassium ion determination [10]. These material advances address key challenges in potentiometric sensing, including signal drift, response time, and detection limits.

Potentiometry, characterized by its fundamental principle of measuring potential under zero-current conditions, offers distinct advantages for chemical analysis across diverse applications. When compared to redox titration methods, direct potentiometry provides more rapid analysis, minimal sample perturbation, and capability for continuous monitoring, while potentiometric redox titrations offer high precision and well-defined endpoints for quantitative analysis. The ongoing development of novel materials, miniaturized designs, and wearable formats promises to expand further the applications and capabilities of potentiometric methods in research, clinical, and field settings.

The Role of the Nernst Equation in Relating Potential to Concentration

In the realm of quantitative chemical analysis, redox titration and potentiometric methods represent two principal approaches for determining analyte concentrations, each with distinct operational principles and performance characteristics. The Nernst equation serves as the fundamental theoretical bridge connecting measured electrical potential to chemical concentration in both methodologies. This electrochemical relationship, formulated by Walther Nernst in 1889, provides the mathematical foundation for understanding how the potential of an electrochemical cell relates to the activities (and thus concentrations) of electroactive species undergoing reduction and oxidation [7] [12]. While both techniques leverage this same fundamental principle, their implementation, precision, and applicability differ significantly across various research contexts, particularly in pharmaceutical development where accurate quantification of active compounds is paramount.

The Nernst equation expresses the dependence of the electrode potential (E) on the standard electrode potential (E°), temperature, and the activities of the oxidized and reduced species involved in the electrochemical reaction. For a general half-reaction: Ox + ze⁻ ⇌ Red, the Nernst equation is expressed as:

[E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}}]

Where E is the electrode potential, E° is the standard electrode potential, R is the universal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, z is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction, F is Faraday's constant, and aRed and aOx represent the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [12]. At room temperature (25°C), this equation simplifies to:

[E = E^0 - \frac{0.05916}{z} \log \frac{[\text{Red}]}{[\text{Ox}]}]

When concentrations are used as approximations for activities [1] [13]. This simplified form reveals that for each tenfold change in the concentration ratio, the electrode potential changes by approximately 59/z mV, establishing a direct quantitative relationship between measurable potential and analyte concentration that forms the basis for both analytical techniques compared in this guide.

Theoretical Foundation: The Nernst Equation

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Expression

The Nernst equation operates as the cornerstone of electrochemical analysis by providing a quantitative relationship between the measurable potential of an electrochemical cell and the concentrations of electroactive species present in solution. This equation derives from thermodynamic principles, specifically relating the actual free-energy change (ΔG) for a reaction under non-standard conditions to the standard free-energy change (ΔG°) [14]:

[ΔG = ΔG° + RT \ln Q]

where Q is the reaction quotient. Substituting the relationships ΔG = -nFEcell and ΔG° = -nFE°cell yields the Nernst equation for a complete electrochemical cell:

[E{\text{cell}} = E^\circ{\text{cell}} - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q]

where Ecell is the actual cell potential, E°cell is the standard cell potential, n is the number of electrons transferred in the overall redox reaction, F is Faraday's constant (96,485 C/mol), and Q is the reaction quotient representing the ratio of product and reactant activities [14]. For the half-cell reaction Ox + ne⁻ → Red, this translates to the familiar form:

[E = E^\circ - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}}]

The equation accurately predicts that the potential becomes identical to the standard electrode potential when the activities of the oxidized and reduced species are equal (Q = 1), as the logarithmic term becomes zero [12] [13].

Formal Potential and Practical Considerations

In practical analytical applications, the use of concentrations rather than activities necessitates introduction of the formal potential (E°'), a modified standard potential that incorporates activity coefficients and other chemical effects [12]. The practical form of the Nernst equation thus becomes:

[E = E^{\circ'} - \frac{0.05916}{n} \log \frac{[\text{Red}]}{[\text{Ox}]} \quad \text{(at 25°C)}]

The formal potential represents the experimentally observed potential when the concentration ratio [Red]/[Ox] equals 1 and all other solution conditions (ionic strength, pH, complexing agents) are specified [12]. This modification is particularly important in pharmaceutical applications where complex matrices can significantly affect electrochemical behavior. The Nernst equation enables prediction of cell potentials under non-standard conditions, determines spontaneous reaction direction, and calculates equilibrium constants [14]. For redox titrations, it predicts the potential change throughout the titration curve, while for direct potentiometry, it provides the direct mathematical relationship between measured potential and analyte concentration.

Visualizing the Electrochemical Relationship

The following diagram illustrates how the Nernst equation provides the fundamental theoretical connection between concentration measurements and potential measurements in electrochemical analysis:

Methodological Comparison: Experimental Protocols

Redox Titration Methodology

Protocol Title: Determination of Ascorbic Acid by Redox Titration with Dichlorophenolindophenol

Principle: This method quantifies reducing analytes through titration with a standardized oxidizing agent, using the distinct potential change at the equivalence point, as predicted by the Nernst equation, for endpoint detection [1] [15].

Materials:

- Analytical balance

- Burette (25 mL)

- Erlenmeyer flasks (250 mL)

- Measuring cylinders

- Pipettes

Reagents:

- Standardized dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) solution (0.01 M)

- Ascorbic acid standard solution

- Sample solution (e.g., fruit juice or pharmaceutical preparation)

- Sulfuric acid (0.1 M) for pH adjustment

Procedure:

- Standardize the DCPIP titrant against a primary ascorbic acid standard (1.0 mM) in triplicate.

- Transfer 25.0 mL of sample solution to a clean Erlenmeyer flask.

- Acidify with 10 mL of 0.1 M sulfuric acid to maintain proper redox conditions.

- Fill the burette with standardized DCPIP solution and record initial volume.

- Titrate with continuous swirling, observing the color change from colorless to pink.

- Record the burette reading at the endpoint and calculate titrant volume.

- Repeat in triplicate for statistical reliability.

Calculations: [C{\text{sample}} = \frac{V{\text{titrant}} \times C{\text{titrant}}}{V{\text{sample}}}]

Where C represents concentration and V represents volume. The Nernst equation governs the abrupt potential change at the endpoint, though visual detection relies on indicator color change [1] [11].

Potentiometric Methodology

Protocol Title: Direct Potentiometric Determination of Iron(II) Concentration

Principle: This method directly relates the measured potential of an indicator electrode to analyte concentration via the Nernst equation, without titrant addition [7] [16].

Materials:

- Potentiometer or pH/mV meter

- Platinum indicator electrode

- Reference electrode (Ag/AgCl or calomel)

- Magnetic stirrer with stir bar

- Volumetric flasks and pipettes

Reagents:

- Standard solutions of Fe²⁺ (0.001 M, 0.01 M, 0.1 M)

- Sample solution containing unknown Fe²⁺ concentration

- Supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M HCl)

Procedure:

- Prepare standard solutions covering the expected concentration range (0.001-0.1 M).

- Place the electrode system in the lowest concentration standard with continuous stirring.

- Allow potential reading to stabilize (approximately 1-2 minutes) and record value.

- Rinse electrodes thoroughly with deionized water between measurements.

- Repeat potential measurements for all standard solutions in order of increasing concentration.

- Measure the sample solution following the same procedure.

- Construct a calibration curve of potential vs. log[Fe²⁺].

Calculations: For direct Nernstian application: [E = E^{\circ'} - \frac{0.05916}{1} \log \frac{[\text{Fe}^{2+}]}{[\text{Fe}^{3+}]}]

In the absence of Fe³⁺, the potential is directly proportional to log[Fe²⁺], enabling concentration determination from the calibration curve [7] [13].

Experimental Workflow Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences between redox titration and direct potentiometric methods:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Method Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of redox titration versus potentiometric methods based on experimental data and theoretical considerations:

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Redox Titration and Potentiometric Methods

| Parameter | Redox Titration | Direct Potentiometry |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Nernst equation predicts equivalence point potential [1] | Nernst equation directly relates E to concentration [7] |

| Accuracy | High (0.5-2% error) with proper indicator selection [11] | Moderate to high (1-5% error) depending on matrix effects [15] |

| Precision | Excellent (RSD < 1%) with experienced analyst [11] | Good (RSD 2-5%) with proper calibration [16] |

| Sensitivity | Moderate (≥10⁻⁴ M typical) [1] | High (down to 10⁻⁶ M possible) [7] |

| Analysis Time | 5-15 minutes per sample [11] | 1-5 minutes per sample after calibration [16] |

| Cost | Low (basic glassware required) [11] | High (electrode and meter investment) [11] |

| Sample Volume | Moderate to large (10-50 mL typical) [1] | Small (1-10 mL possible) [7] |

| Matrix Effects | Moderate susceptibility [15] | High susceptibility requiring ISAB [7] |

| Operator Skill | Higher requirement for endpoint detection [11] | Lower requirement with automation [11] |

| Applications | Well-defined redox systems [1] | Broad including reversible systems [7] |

Experimental Data Comparison

The following table presents representative experimental data obtained from pharmaceutical analysis applications for both techniques:

Table 2: Experimental Data from Pharmaceutical Analysis Applications

| Analyte | Method | Titrant/Electrode | Linear Range | Recovery (%) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascorbic Acid | Redox Titration | DCPIP [15] | 0.1-10 mM | 98-102 | 0.8-1.5 |

| Ascorbic Acid | Potentiometric | Pt electrode [15] | 0.01-1 mM | 95-105 | 2.1-3.5 |

| Iron(II) | Redox Titration | Cerium(IV) [1] | 0.5-50 mM | 99-101 | 0.5-1.2 |

| Iron(II) | Potentiometric | Pt electrode [7] | 0.001-10 mM | 97-103 | 1.8-2.9 |

| Polyphenols | Redox Titration | Ti(III) [15] | 0.05-5 mM | 90-110 | 3.5-5.0 |

| Polyphenols | Potentiometric | Pt electrode [15] | 0.01-2 mM | 85-115 | 5.0-8.0 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Platinum Electrode | Inert indicator electrode for redox potential measurements [1] | Potentiometric detection of Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ ratio [15] |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Stable reference potential with constant chloride concentration [1] | Provides reference potential in potentiometric cells [16] |

| Calomel Electrode | Alternative reference electrode (Hg/Hg₂Cl₂) [1] | Reference electrode in non-biological applications [16] |

| Potassium Permanganate | Strong oxidizing titrant with self-indicating properties [1] | Determination of iron(II) and other reductants [11] |

| Cerium(IV) Sulfate | Powerful oxidizing agent, primary standard [1] | Quantitative oxidation of organic pharmaceuticals [11] |

| Sodium Thiosulfate | Reducing titrant for iodine-based titrations [1] | Iodometric determination of oxidizing agents [11] |

| Dichlorophenolindophenol | Oxidizing titrant and redox indicator [15] | Specific determination of ascorbic acid [15] |

| Titanium(III) Chloride | Strong reducing titrant [15] | Determination of oxidized compounds in complex matrices [15] |

| Ferroin Indicator | Redox indicator (E° = 1.06 V) [1] | Visual endpoint detection in cerimetric titrations [11] |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster | Minimizes activity coefficient variations [7] | Standardization of medium in direct potentiometry [7] |

Critical Evaluation in Research Applications

Limitations and Practical Considerations

While both techniques derive their theoretical foundation from the Nernst equation, significant practical limitations emerge in research applications, particularly with complex sample matrices. Potentiometric methods face challenges when dealing with irreversible redox systems or samples containing multiple interfering species that can adsorb onto electrode surfaces, fundamentally violating the Nernstian assumptions [15]. Research on wine analysis highlights that adsorption of tannins and polyphenols on platinum electrodes creates mixed potentials, making Nernst equation application problematic and resulting in poor reproducibility [15].

Redox titrations encounter limitations with slow reaction kinetics, particularly when analyzing complex organic antioxidants. The titration of polyphenols with DCPIP demonstrates significant time dependence, where the slow reaction kinetics make identification of the true equivalence point challenging, regardless of the detection method [15]. This limitation is particularly relevant in pharmaceutical analysis where many active compounds exhibit slow electron transfer kinetics.

Method Selection Guidelines

Selection between these analytical approaches depends on multiple factors:

- For well-defined, fast redox systems with adequate analyte concentration, redox titration provides excellent accuracy and precision with minimal equipment investment [11].

- For dilute solutions or rapid analysis, direct potentiometry offers advantages despite higher initial costs [11].

- For complex matrices with multiple redox components, neither method may provide accurate quantitative results without preliminary separation, though redox titration often shows better robustness [15].

- When developing methods for new pharmaceutical compounds, preliminary assessment of reaction reversibility (via cyclic voltammetry) is recommended before selecting an electrochemical quantification approach [15].

The Nernst equation provides the fundamental theoretical connection between electrical potential and chemical concentration that underpins both redox titration and potentiometric methods. While sharing this common theoretical foundation, these techniques represent distinct approaches with complementary strengths and limitations in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Redox titration excels in accuracy, precision, and cost-effectiveness for standardized analyses of well-behaved redox systems, while direct potentiometry offers superior sensitivity, rapid analysis, and automation potential despite higher equipment costs and greater matrix susceptibility. The choice between methodologies must consider the specific analytical requirements, sample matrix complexity, available resources, and required throughput. Advances in electrode design and digital instrumentation continue to expand the applications of both techniques in pharmaceutical analysis, maintaining the Nernst equation's central role in converting electrical measurements to chemical concentration data nearly a century after its formulation.

Titrimetric analysis serves as a cornerstone of quantitative chemical analysis in research and industrial laboratories. Within this framework, redox titrimetry and potentiometric methods represent two powerful, yet distinct, approaches for determining analyte concentrations. Redox titrations monitor the transfer of electrons between reacting species, while potentiometric titrations measure the potential difference across an electrochemical cell to identify the titration's endpoint. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these methods can significantly impact the precision, accuracy, and applicability of analytical results. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these two titrimetric techniques, focusing on the characterization of redox titration curves, with supporting experimental data and protocols to inform method selection for specific analytical challenges.

Theoretical Foundations

Redox Titration Curves

Redox titrations leverage oxidation-reduction reactions where the titrand in a reduced state reacts with a titrant in an oxidized state (or vice versa). The progression of the reaction is monitored by tracking the potential of the reaction mixture, which is governed by the Nernst equation [17].

For a generalized redox reaction: [A{red} + B{ox} \rightleftharpoons B{red} + A{ox}] the reaction's potential, (E{rxn}), is the difference between the reduction potentials of the involved half-reactions [17]: [E{rxn} = E{B{ox}/B{red}} - E{A{ox}/A{red}}]

The resulting titration curve is a plot of the measured potential (in mV or V) versus the volume of added titrant. Its characteristic sigmoidal shape features a steep inflection point at the equivalence point, where the number of moles of titrant added stoichiometrically equals the number of moles of analyte in the sample [17]. To clarify the identity and abundance of species in solution, it is fundamental to know these formation constants, which are primarily determined through techniques like potentiometry [18].

Potentiometric Titration Methods

Potentiometric titration is a quantitative analytical technique that determines the concentration of an analyte by measuring the potential difference between two electrodes (indicator and reference) in the solution as titrant is added [19]. The endpoint is identified by a significant change in this potential difference. A titration curve is plotted, and the endpoint can be precisely determined from the maximum of the first derivative curve or the zero point of the second derivative curve [19].

This method is highly versatile and can be applied to acid-base, precipitation, complexometric, and redox reactions [19]. For redox titrations, inert metal electrodes like platinum are typically employed [19].

Comparative Analysis: Redox vs. Potentiometric Titrations

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of redox and potentiometric titration methods for the analysis of redox-active species.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Redox and Potentiometric Titration Methods

| Feature | Redox Titration (with Visual Indicators) | Potentiometric Redox Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Monitoring electron transfer via color change of a redox indicator [17] | Measurement of potential difference between indicator and reference electrode [19] |

| Endpoint Detection | Visual observation of indicator color change [17] | Graphical analysis of potential vs. volume curve; use of 1st or 2nd derivatives for precision [19] |

| Data Output | Qualitative visual cue; single volume reading at endpoint for calculation [17] | Quantitative, full titration curve ((E) vs. (V)) providing complete reaction progress data [7] [19] |

| Key Equipment | Burette, conical flask, redox indicator [17] | Potentiometer, inert indicator electrode (e.g., Pt), reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) [19] |

| Advantages | Simple, rapid, requires minimal equipment [17] | Applicable to colored/turbid solutions; provides entire reaction profile; higher objectivity and precision [19] |

| Limitations | Subjective; requires clear visual endpoint; unsuitable for colored solutions [17] | Requires more sophisticated and costly instrumentation [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Characterizing a Redox Titration Curve Potentiometrically

This protocol outlines the steps to generate a full redox titration curve using potentiometric detection, allowing for precise determination of the equivalence point without a visual indicator [19].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Analyte Solution: The solution containing the redox-active species of unknown concentration.

- Titrant Solution: Standardized solution of a strong oxidizing or reducing agent (e.g., KMnO₄, K₂Cr₂O₇, Fe²⁺).

- Supporting Electrolyte: (e.g., 1 M H₂SO₄) to maintain ionic strength and provide suitable pH.

- Potentiometer (or pH meter capable of measuring mV) [19].

- Indicator Electrode: Platinum wire or foil electrode [19].

- Reference Electrode: Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) or Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) [19].

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bar.

- Burette.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Transfer a known, precise volume of the analyte solution into the titration vessel. Add the supporting electrolyte to ensure sufficient conductivity and a stable pH environment for the redox reaction [7].

- Instrument Setup: Place the titration vessel on the magnetic stirrer. Immerse the cleaned platinum indicator electrode and the reference electrode into the solution. Connect both electrodes to the potentiometer. Begin gentle stirring to ensure homogeneity without vortex formation [19].

- Perform Titration:

- Record the initial potential reading before any titrant is added.

- Add the titrant in small, measured increments. Before each addition, ensure the potential reading has stabilized.

- After each addition, record the precise volume of titrant added and the corresponding stable potential (in mV). In regions where the potential change is slow, larger increments can be used. Decrease the increment size significantly in the region of the anticipated equivalence point (where the potential change per volume unit becomes large).

- Continue the titration several milliliters past the equivalence point, noting that the potential change will again become gradual [19].

- Data Analysis and Plotting:

- Plot the measured potential (E) against the volume of titrant added (V) to obtain the sigmoidal titration curve.

- Calculate the first derivative (ΔE/ΔV) of the curve and plot it against the volume. The volume corresponding to the maximum of this derivative plot is the equivalence point [19].

- For the highest precision, a second derivative plot can be used, where the equivalence point is where the value crosses zero [19].

Protocol 2: Direct Redox Titration with a Visual Indicator

This traditional method is suitable when a sharp, unambiguous color change is available and the solution is not colored.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Analyte Solution

- Standardized Titrant Solution (e.g., Cerium(IV) salts in acidic medium)

- Visual Redox Indicator (e.g., Ferroin, Diphenylamine sulfonic acid) selected to change color near the reaction's equivalence point [17].

- Burette, conical flask, burette stand, pipette.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Titrant Standardization: If not using a commercially prepared standard solution, standardize the titrant against a primary standard (e.g., sodium oxalate for KMnO₄).

- Sample Preparation: Using a volumetric pipette, transfer a known, precise volume of the analyte solution into a clean conical flask.

- Add Indicator: Add a few drops of the appropriate redox indicator to the flask [17].

- Titration: Slowly add the titrant from the burette to the analyte solution with continuous swirling. Initially, the color change upon mixing may be transient. Continue until a single drop of titrant causes a persistent color change throughout the solution. This is the visual endpoint [17].

- Recording: Note the final burette reading.

- Calculation: Use the reaction stoichiometry, the concentration of the titrant, and the volume of titrant used to calculate the concentration of the analyte. For monoprotic acids, this can utilize the relationship (C1V1 = C2V2), though this must be adapted for the specific redox reaction stoichiometry [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Redox Titration Analysis

| Item | Function / Application Notes |

|---|---|

| Potentiometer | Measures the potential difference (in mV) between the indicator and reference electrodes. Modern models may interface directly with software for data acquisition [19]. |

| Inert Indicator Electrode (Pt) | Serves as the sensor for the solution's redox potential. Platinum is ideal due to its inertness and conductivity. It does not participate in the reaction but provides a surface for electron exchange [19]. |

| Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) | Provides a stable, known, and fixed potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured, completing the electrochemical cell [19]. |

| Standardized Titrants | Common oxidizing agents include KMnO₄, K₂Cr₂O₇, and Ce(IV) salts. Common reducing agents include Fe(II) salts and sodium thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) [17]. |

| Visual Redox Indicators | Compounds that change color upon being oxidized or reduced (e.g., Ferroin). The midpoint of their color change should be close to the formal potential of the analyte reaction for accurate results [17]. |

| Data Analysis Software | Specialized software is used for refining constants from potentiometric data, though current tools can suffer from limitations and require careful data generation [18]. |

Critical Factors Influencing Titration Curves

Several factors are crucial for obtaining accurate and precise results from both redox and potentiometric titrations.

Reaction Completeness and Formal Potential: The magnitude of the change in potential at the equivalence point is directly related to the difference between the formal potentials of the titrant and analyte half-reactions. A larger difference results in a more pronounced inflection in the curve, making the endpoint clearer and the analysis more robust [17].

Measurement Precision (pH and Volume): The precision of calculated concentrations and constants is highly dependent on the standard errors in measuring both pH (or potential) and the volume of titrant added. Meticulous technique and calibrated instrumentation are non-negotiable for high-quality data [21].

Ionic Strength and Activity Coefficients: The Nernst equation is defined in terms of ion activities, not concentrations. Variations in ionic strength during a titration can alter activity coefficients, potentially introducing errors in refined constants if not accounted for. Using a high and relatively constant concentration of an inert supporting electrolyte can mitigate this effect [7] [18].

Systematic Errors: Errors from electrode calibration, inaccurate knowledge of reagent concentrations, or improper electrode handling can systematically bias the results. Rigorous calibration and standardized protocols are essential to minimize these errors [18].

The characterization of redox titration curves is a fundamental skill in analytical chemistry, with critical applications from drug development to environmental monitoring. While direct redox titration with visual indicators offers simplicity, the potentiometric method provides a superior level of objectivity, precision, and rich data, making it the preferred choice for research and method development. The decision to use one approach over the other, or a hybrid of both, should be guided by the specific requirements of the analysis, including the required precision, the nature of the solution, and the available resources. By understanding the principles outlined in this guide and adhering to the detailed protocols, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful techniques to obtain reliable and meaningful analytical data.

In electrochemical analysis, the accurate measurement of potential or current relies on a complete cell comprising three fundamental components: an indicator electrode, a reference electrode, and a salt bridge. These elements form the cornerstone of both potentiometric methods and redox titrations, techniques indispensable to modern chemical analysis, pharmaceutical development, and clinical diagnostics. In potentiometry, the potential of an electrochemical cell is measured under static (zero-current) conditions to determine analyte activity or concentration, guided by the Nernst equation [22] [1]. Redox titrations, in contrast, monitor the progress of an oxidation-reduction reaction between an analyte and a titrant, with the endpoint often determined potentiometrically by tracking the potential change of the indicator electrode relative to the reference electrode [1] [11]. The performance, accuracy, and reliability of these analytical techniques are critically dependent on the proper selection and function of these three key components. This guide provides a detailed comparison of their characteristics, supported by experimental data and standardized testing protocols, to inform researchers and scientists in their method development.

Performance Comparison of Key Components

The following tables summarize the core functions, ideal characteristics, and common types of indicator electrodes, reference electrodes, and salt bridges, providing a consolidated overview for informed selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Indicator and Reference Electrodes

| Feature | Indicator Electrode (Working Electrode) | Reference Electrode |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Responds to the activity of the analyte of interest [22] [1]. | Provides a stable, constant, and known reference potential [22] [1]. |

| Potential | Varies with analyte concentration (Nernstian response) [1]. | Stable and invariant under measurement conditions [23]. |

| Key Characteristic | High sensitivity and selectivity for the target species [24] [25]. | Minimal junction potential; insensitive to sample composition [23]. |

| Common Types | - Inert Metal (Pt, Au): For redox titrations [1] [11].- Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISE): e.g., glass pH electrode [22].- Modified Carbon Electrodes: e.g., CPE, GCE, SPCE [24] [25]. | - Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) [1].- Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) [1].- Liquid-junction free with polymer membranes [26] [23]. |

Table 2: Composition and Characteristics of Salt Bridges

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Primary Function | Completes the electrical circuit between the two half-cells while preventing mixing of solutions [22]. |

| Key Requirement | Contains an inert electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃) with ions of similar mobility (equitransferent) to minimize liquid junction potential [22] [23]. |

| Ideal Characteristics | - Chemically inert.- High concentration of electrolyte.- Stable and reproducible junction potential [23]. |

| Common Materials | Agar or gelatin gels saturated with an electrolyte like KCl [22]. |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Evaluation

To ensure reliable and reproducible electrochemical measurements, standardized testing of these key components is essential. The following protocols are adapted from rigorous research methodologies.

Protocol for Reference Electrode Stability and Interference Testing

A comprehensive evaluation of reference electrode performance should assess its stability and susceptibility to sample-induced errors [23].

1. Experimental Workflow: The logical sequence for testing is outlined below.

2. Methodology:

- Electrode Fabrication: Prepare polymer-based reference electrodes by dispersing an equitransferent salt (e.g., KCl or a highly lipophilic organic salt) into a polymer matrix such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or polyurethane (PU). The mixture is then cast and cured into a membrane [23].

- Stability Over Time: Immerse the reference electrode and a validated external reference (e.g., SCE) in a stable electrolyte solution. Measure the potential difference between them over a period of several hours to days. A stable electrode will show a potential drift of less than ±1 mV [23].

- pH Sensitivity Test: Place the reference electrode in a series of buffer solutions with identical ionic strength but varying pH (e.g., from pH 3 to 9). Measure the potential. An ideal reference electrode shows less than ±0.5 mV change per pH unit, indicating no significant pH sensitivity [23].

- Ionic Strength/Interference Test: Test the electrode in solutions with a fixed background of interfering ions but varying ionic strength (e.g., 0.01 M to 0.1 M NaCl or CaCl₂). The potential should remain constant. As highlighted in recent studies, even a minimal excess (0.11%) of lipophilic cationic sites in the membrane can induce a significant anionic response, converting a reference membrane into an anion-selective membrane [26].

- Data Analysis: Plot the measured potential versus the parameter tested (time, pH, ionic strength). The slope of the trendline quantifies the electrode's stability and susceptibility to interference.

Protocol for Potentiometric Redox Titration

This protocol details a standard method for using the key components to detect the endpoint of a redox titration, such as the determination of iron(II) with cerium(IV) [1] [11].

1. Experimental Workflow: The key steps for performing a potentiometric redox titration are as follows.

2. Methodology:

- Cell Assembly: Construct an electrochemical cell. The indicator electrode is typically an inert wire such as platinum or gold. The reference electrode can be a SCE or Ag/AgCl electrode. A salt bridge (e.g., filled with KNO₃ or KCl agar) connects the two half-cells, completing the circuit without mixing the solutions [1] [11].

- Titrant Addition & Potential Measurement: Add the titrant (e.g., 0.1 M Ce⁴⁺) incrementally to the analyte solution (e.g., Fe²⁺ in acidic medium). After each addition, measure the equilibrium cell potential (E_cell) under static conditions. The potential is given by

E_cell = E_indicator - E_reference + E_liquid_junction[1]. - Endpoint Determination: Record the potential (E) and the volume of titrant added (V). Plot the data to generate a titration curve (E vs. V). The equivalence point is identified as the volume at the steepest point of the sigmoidal curve. This can be precisely located by calculating the first derivative (ΔE/ΔV vs. V) and finding its maximum, or the second derivative (Δ²E/ΔV² vs. V) and finding its zero-crossing [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful experimentation requires high-quality materials. The following table lists key items used in the construction and use of the three key components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Platinum (Pt) or Gold (Au) Wire | Serves as an inert indicator electrode for redox titrations, providing a surface for electron transfer without participating in the reaction [1] [11]. |

| Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE) | A versatile and renewable substrate for indicator electrodes; can be modified with conductive materials to enhance sensitivity for specific drugs [24]. |

| Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) Wire | A common, robust internal element for reference electrodes of the second kind [1] [23]. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl), High Purity | The standard electrolyte for salt bridges and reference electrode fillers due to its nearly equitransferent ions, minimizing liquid junction potential [22] [23]. |

| Agarose / Agar | A gelling agent used to solidify electrolyte solutions within salt bridges, preventing convective mixing while allowing ionic conduction [22]. |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) & Plasticizers | Polymers used to fabricate robust, solid-contact membranes for both ion-selective indicator electrodes and reference electrodes [23]. |

| Lipophilic Salts (e.g., ETH 500) | Incorporated into polymer membranes to impart high lipophilicity, which enhances the lifetime of reference electrodes and alleviates ion-exchange interference. Note: Purity is critical, as minor impurities can dominate performance [26]. |

| Standard Buffer Solutions | Required for the calibration of pH indicator electrodes and for testing the pH sensitivity of reference electrodes [27] [23]. |

Applied Techniques: Implementing Titration Methods in Pharmaceutical Workflows

Redox titrations are a cornerstone of quantitative chemical analysis, with specific titrants like potassium permanganate (KMnO4), potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7), iodine, and sodium thiosulfate being indispensable in various industrial and research settings. Within the broader context of analytical chemistry, the choice between classical redox titration methods and modern potentiometric methods is crucial. Potentiometry, which measures the potential between a reference and an indicator electrode under static conditions, offers a complementary approach that can enhance precision, enable automation, and provide insights into reaction fundamentals [28] [7]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these four common redox titrants and examines the experimental data supporting their use in advanced research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Common Redox Titrants

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, applications, and performance data of the four titrants, providing a basis for objective comparison.

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Performance of Common Redox Titrants

| Titrant | Primary Role & Nature | Standardization Requirements & Stability | Common Analytes & Applications | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMnO₄ | Strong oxidizing agent [29] | Not a primary standard; requires standardization against sodium oxalate, arsenic trioxide, or iron wire [30] [29]. Solution decomposes slowly and needs restandardization [29]. | Oxalic acid, hydrogen peroxide, iron (II) salts [30] [29]. Widely used in environmental and chemical analysis. | Serves as a self-indicator [30] [29]. Oxidizing power depends on the medium (acidic, alkaline, or neutral) [29]. Cannot be used in HCl solutions as it oxidizes Cl⁻ [29]. |

| K₂Cr₂O₇ | Moderately strong oxidizing agent [31] | Primary standard; can be used to prepare a solution directly by dissolving dried solid [29]. Highly stable [29]. | Iron (II) [29]. Used for the indirect determination of oxidants like nitrates and peroxides [29]. | Requires a redox indicator (e.g., diphenylamine sulfonic acid) [29]. A key advantage is that it does not oxidize HCl, allowing its use in hydrochloric acid media [29]. |

| Iodine (I₂) | Weak oxidizing agent [29] [31] | Not a primary standard; requires standardization with sodium thiosulfate or arsenic trioxide [30] [29]. Volatile; solutions require restandardization [29]. | Strong reducing agents like arsenite, sulfite, and ascorbate (in iodimetry) [29]. | Starch is used as an indicator, forming a deep-blue complex [30] [29]. Titrations must be performed in neutral or weakly alkaline conditions to prevent side reactions [30]. |

| Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) | Moderately strong reducing agent (for iodine titrations) [29] | Not a primary standard; requires standardization with potassium iodate or potassium dichromate [30] [29]. Affected by pH, microorganisms, and light; requires restandardization [29]. | Oxidizing agents like KIO₃, K₂Cr₂O₇, and Cu²⁺ (in iodometry) [30] [29]. | Used indirectly in iodometry to titrate iodine liberated from redox reactions [29] [31]. The reaction produces the colorless tetrathionate ion [30]. |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Detailed methodologies are critical for obtaining accurate and reproducible results. Below are standardized protocols for key experiments involving these titrants.

Standardization of KMnO₄ with Sodium Oxalate

This protocol ensures the accurate determination of KMnO₄ concentration, which is unstable over time.

- Workflow Overview:

- Detailed Procedure:

- Primary Standard Solution: Dissolve an accurately weighed quantity of pure, dry sodium oxalate (approximately 6.7 g for a 1L 0.05 M solution) in water and make up to the mark in a volumetric flask [30].

- Titration Setup: Pipette 20 mL of the sodium oxalate solution into a conical flask. Add approximately 5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid [30].

- Titration: Warm the solution to about 70°C to facilitate the reaction. Titrate with the KMnO₄ solution while hot, until a faint pink color persists for at least 30 seconds. The purple color of MnO₄⁻ disappears as it is reduced to nearly colorless Mn²⁺, with the endpoint signaled by the first trace of excess titrant [30] [29].

- Calculation: The reaction stoichiometry is 2 KMnO₄ to 5 Na₂C₂O₄. Use the mass of sodium oxalate and the volume of KMnO₄ consumed to calculate the exact molarity of the KMnO₄ solution [30].

Iodometric Determination of an Oxidizing Agent (K₂Cr₂O₇)

This indirect method is a classic example of iodometry, used to determine strong oxidizing agents.

- Workflow Overview:

- Detailed Procedure:

- Liberation of Iodine: To an acidic solution of the oxidizing analyte (e.g., K₂Cr₂O₇) in an iodine flask, add a known excess of potassium iodide (KI). The oxidizing agent (e.g., Cr₂O₇²⁻) will quantitatively oxidize I⁻ to I₂ [30] [29]. Stoichiometric example: Cr₂O₇²⁻ + 6I⁻ + 14H⁺ → 2Cr³⁺ + 3I₂ + 7H₂O [30].

- Titration: Titrate the liberated iodine with a standardized sodium thiosulfate solution. The solution will change from brown to pale yellow [30].

- Endpoint Detection: When the color becomes a faint straw-yellow, add a few milliliters of a fresh starch solution. Starch forms an intense blue complex with I₂. Continue titration until the blue color disappears, leaving a colorless solution [30] [29]. The reaction is: I₂ + 2S₂O₃²⁻ → 2I⁻ + S₄O₆²⁻ [30] [29].

- Calculation: Based on the stoichiometry of the initial oxidation reaction and the thiosulfate titration, calculate the concentration of the original oxidizing agent.

Redox Titration vs. Potentiometric Methods

The integration of potentiometric methods represents a significant advancement in redox analysis. Potentiometry measures the potential of an electrochemical cell under static conditions (with negligible current), relating this potential to analyte activity via the Nernst equation [7]. This framework allows for a direct comparison with classical indicator-based titrations.

Table 2: Comparison of Redox Titration and Potentiometric Methodologies

| Aspect | Classical Redox Titration | Potentiometric Method |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Visual or indicator-based detection of the titration endpoint [30] [29]. | Measurement of electrochemical potential change using an indicator electrode versus a reference electrode [7]. |

| Endpoint Detection | Subjective; relies on color change of self-indicators (KMnO₄) or added redox indicators [30] [27]. | Objective; endpoint is the maximum slope (inflection point) on a potential vs. titrant volume curve, determined instrumentally [7]. |

| Automation & Data Handling | Manual titration is labor-intensive. Automated systems are available but require specific setup [27]. | Highly amenable to automation; systems can be controlled by software for high precision and reproducibility [28] [32]. |

| Sample Versatility | Effective for colored or turbid solutions where visual detection is still possible [27]. | Electrode performance can be compromised by high-salt, oily, or viscous samples that foul the electrode surface [27]. |

| Accuracy & Precision | High accuracy in well-controlled systems, but precision can be affected by subjective endpoint interpretation [27]. | Capable of very high precision and accuracy (e.g., uncertainties < 0.01% with coulometric titration), reducing human error [32]. |

| Primary Applications | Routine quality control in various industries (food, beverage, pharmaceuticals) where cost and simplicity are key [29] [27]. | Research, development, and high-stakes quality control requiring traceable data (e.g., certified reference materials) [32] [33]. |

The decision-making process for method selection can be visualized as follows:

Modern research increasingly leverages the strengths of both methods. For instance, Python is now used to automate and simulate potentiometric redox titrations, enhancing precision and providing a framework for data analysis that bridges the gap between classical technique and computational chemistry [28]. Furthermore, the market for potentiometric titrators is growing, with the redox segment holding a major share, driven by demand from pharmaceutical and chemical manufacturing for accurate and automated analysis [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A well-equipped lab requires specific, high-purity materials to ensure analytical accuracy.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Redox Experiments

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Primary Standards (e.g., Sodium Oxalate, Potassium Dichromate, Arsenic Trioxide) | High-purity compounds used to determine the exact concentration (standardize) of titrant solutions [30] [29]. |

| Redox Indicators (e.g., Ferroin, Diphenylamine sulfonic acid) | Compounds that change color at a specific electrode potential, used to detect the endpoint of titrations where no self-indicator is present [29]. |

| Starch Indicator | Forms a deep-blue complex with iodine, used as a highly sensitive indicator in iodometric and iodimetric titrations [30] [29]. |

| Potentiometric System (Reference Electrode, Indicator Electrode e.g., Pt, Potentiometer) | Used to measure the electrochemical potential of a solution without a visual indicator, allowing for objective endpoint detection [7] [29]. |

| Specialized Glassware (Iodine Flasks, Burettes with glass stoppers) | Iodine flasks prevent volatile iodine from escaping. Glass-stoppered burettes are essential for KMnO₄, which can degrade rubber [30] [29]. |