Redox Titration Protocols for Metal Ion Determination: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Quality Control

This article provides a comprehensive guide to redox titration for metal ion analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Redox Titration Protocols for Metal Ion Determination: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Quality Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to redox titration for metal ion analysis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of redox reactions and Nernst equation applications, explores specific methodological protocols for determining iron, antimony, and tin, and offers practical troubleshooting for common laboratory errors. The content also validates the technique through comparisons with modern spectroscopic and chemosensing methods, highlighting its enduring relevance in pharmaceutical quality control, environmental monitoring, and the study of metal ions in biological systems for clinical research applications.

Understanding Redox Titration: Core Principles and Historical Development for Metal Ion Analysis

The Basic Principles of Oxidation-Reduction Reactions in Titrimetry

Oxidation-reduction (redox) titrimetry is a foundational analytical method based on electron-transfer reactions between a titrant and an analyte. These reactions involve characteristic changes in oxidation states, providing a robust framework for quantifying diverse analytes, particularly metal ions. The development of redox titrimetry dates back to 1787 when Claude Berthollet introduced a method for analyzing chlorine water based on its ability to oxidize indigo [1]. The field expanded significantly in the mid-1800s with the introduction of standardized titrants like MnO₄⁻, Cr₂O₇²⁻, and I₂ as oxidizing agents, and Fe²⁺ and S₂O₃²⁻ as reducing agents [1]. Within metal ion determination research, redox titration protocols offer precise, reproducible, and cost-effective quantification of metal concentrations across environmental, pharmaceutical, and industrial applications. This article details the core principles, essential methodologies, and practical applications of redox titrimetry with a specific focus on metal ion analysis, providing researchers with standardized protocols for implementation.

Theoretical Foundations

Redox titrations are governed by the principles of electron transfer, where one species (the reducing agent) donates electrons and another (the oxidizing agent) accepts them. The titration curve, which plots the reaction potential against the volume of titrant added, is critical for evaluating these analyses [1] [2]. Unlike acid-base titrations that monitor pH, redox titrations track the system's electrochemical potential.

The reaction potential ((E{\text{rxn}})) is derived from the difference between the reduction potentials of the titrant and analyte half-reactions. For a generalized reaction: [ A{\text{red}} + B{\text{ox}} \rightleftharpoons B{\text{red}} + A{\text{ox}} ] the reaction potential is given by: [ E{\text{rxn}} = E{B{\text{ox}}/B{\text{red}}} - E{A{\text{ox}}/A{\text{red}}} ] where (E{B{\text{ox}}/B{\text{red}}}) and (E{A{\text{ox}}/A{\text{red}}}) are the reduction potentials for the titrant and analyte half-reactions, respectively [1].

The Nernst equation relates the potential of a solution to the concentrations of the participating species at any point in the titration. Before the equivalence point, the potential is most conveniently calculated using the analyte's half-reaction: [ E{\text{rxn}} = E^o{A{\text{ox}}/A{\text{red}}} - \frac{RT}{nF}\ln\frac{[A{\text{red}}]}{[A{\text{ox}}]} ] After the equivalence point, the titrant's half-reaction is used: [ E{\text{rxn}} = E^o{B{\text{ox}}/B{\text{red}}} - \frac{RT}{nF}\ln\frac{[B{\text{red}}]}{[B{\text{ox}}]} ] In practice, matrix-dependent formal potentials often replace standard state potentials for improved accuracy [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Common Redox Titrants in Metal Ion Analysis

| Titrant | Primary Role | Common Analyte | Reaction Medium | Endpoint Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | Oxidizing Agent | Fe²⁺, Oxalic Acid | Acidic (H₂SO₄) | Self-indicating (colorless to pink) [2] |

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Oxidizing Agent | Fe²⁺ | Acidic | Redox Indicator (e.g., Diphenylamine) [1] |

| Iodine (I₂) | Oxidizing Agent | Thiosulfate (S₂O₃²⁻) | Neutral/Slightly Acidic | Starch Indicator (blue to colorless) [3] |

| Cerium(IV) Salts | Oxidizing Agent | Fe²⁺ | Acidic | Redox Indicator [1] |

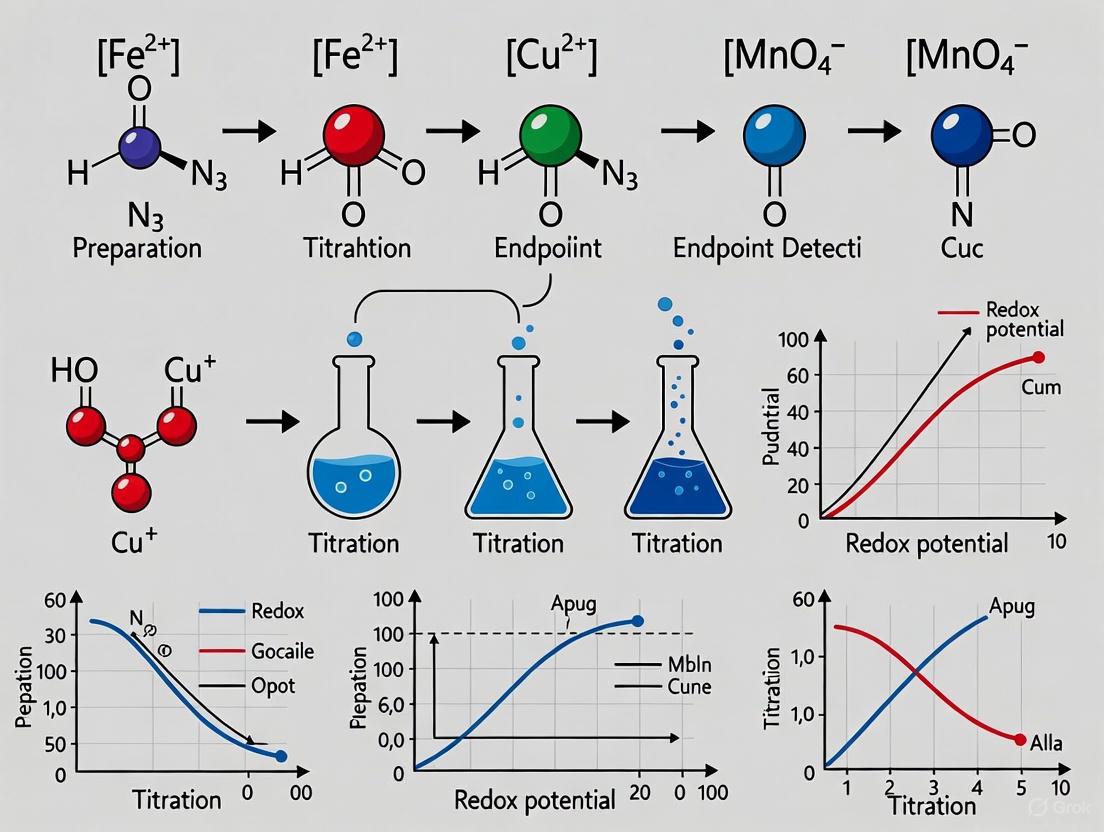

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate redox titration method based on the analyte and method requirements:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Ferrous Ions Using Potassium Permanganate

Principle

This method quantifies ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) concentration through titration with potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) in an acidic medium. KMnO₄ serves as both an oxidizing titrant and an indicator. In acidic conditions, the permanganate ion (MnO₄⁻) is reduced to nearly colorless manganous ions (Mn²⁺), while Fe²⁺ is oxidized to Fe³⁺. The first persistent pale pink color signals the endpoint, indicating that all Fe²⁺ has been oxidized and excess MnO₄⁻ is present [4] [2].

The principal redox reactions are:

- Reduction of permanganate: [ \text{MnO}4^{-} + 8\text{H}^+ + 5e^- \rightarrow \text{Mn}^{2+} + 4\text{H}2\text{O} ]

- Oxidation of ferrous ions: [ \text{Fe}^{2+} \rightarrow \text{Fe}^{3+} + e^- ]

- Overall ionic equation: [ \text{MnO}4^{-} + 5\text{Fe}^{2+} + 8\text{H}^+ \rightarrow \text{Mn}^{2+} + 5\text{Fe}^{3+} + 4\text{H}2\text{O} ]

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ferrous Ion Determination

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Purity | Function in Protocol | Safety Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | 0.02 M Standard Solution | Oxidizing Titrant | Oxidizer; handle with gloves |

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | 1 M Dilute Solution | Provides Acidic Medium | Severe burn hazard; use in fume hood |

| Ferrous Ammonium Sulfate | Analytical Grade | Analyte/Sample | Irritant; avoid inhalation |

| Deionized Water | N/A | Solvent & Rinsing | N/A |

| Burette | Class A | Titrant Dispensing | N/A |

| Volumetric Flask | Class A, 250 mL | Solution Preparation | N/A |

| Piper | Class A | Sample/Reagent Transfer | N/A |

| Conical Flask | 250 mL | Titration Vessel | N/A |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Standard KMnO₄ Solution Preparation: Accurately prepare a 0.02 M KMnO₄ solution. Standardize against primary standard oxalic acid if necessary [2].

- Sample Preparation: Weigh accurately approximately 1.0 g of the ferrous salt (e.g., ferrous ammonium sulfate hexahydrate) and dissolve in approximately 50 mL of deionized water in a 250 mL conical flask.

- Acidification: Carefully add 20 mL of 1 M sulfuric acid to the sample solution to create the required acidic medium.

- Titration: Fill a clean burette with the standardized KMnO₄ solution. Titrate the acidified sample solution with continuous swirling.

- Endpoint Determination: The initial purple color of the permanganate will decolorize upon addition as Fe²⁺ is oxidized. Continue titration until the first permanent pale pink color persists for at least 30 seconds.

- Blank Determination: Perform a blank titration using all reagents except the ferrous sample to correct for any titrant consumption by impurities.

- Calculation: Calculate the percentage of Fe²⁺ in the sample using the following formula: [ \% \text{Fe}^{2+} = \frac{V{\text{KMnO4}} \times M{\text{KMnO4}} \times 5 \times M{\text{Fe}} \times 100}{W{\text{sample}} \times 1000} ] where:

- (V_{\text{KMnO4}}) = volume of KMnO₄ used (mL)

- (M_{\text{KMnO4}}) = molarity of KMnO₄ solution (M)

- (M_{\text{Fe}}) = atomic mass of iron (55.845 g/mol)

- (W_{\text{sample}}) = mass of the sample (g)

- The factor of 5 arises from the stoichiometry (1 mol MnO₄⁻ reacts with 5 mol Fe²⁺)

Protocol 2: Iodometric Determination of Oxidizing Agents

Principle

Iodometric titration is an indirect method for determining oxidizing agents. The analyte oxidizes iodide (I⁻) to iodine (I₂), and the liberated iodine is then titrated with a standard sodium thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) solution. Starch indicator is added near the endpoint, forming a blue complex with iodine, which disappears when all iodine is reduced to iodide, signaling the endpoint [3].

Key reactions:

- Liberation of iodine by oxidizing agent (example with copper): [ 2\text{Cu}^{2+} + 4\text{I}^- \rightarrow 2\text{CuI}(s) + \text{I}_2 ]

- Titration with thiosulfate: [ \text{I}2 + 2\text{S}2\text{O}3^{2-} \rightarrow 2\text{I}^- + \text{S}4\text{O}_6^{2-} ]

- Iodine Liberation: To the analyte solution in a conical flask, add an excess of potassium iodide (KI). The oxidizing agent will liberate iodine, producing a yellow-to-brown color.

- Titration: Titrate the liberated iodine with standardized sodium thiosulfate solution until the color fades to pale yellow.

- Starch Addition: Add 1-2 mL of fresh starch solution. A deep blue color will appear.

- Endpoint Determination: Continue titration until the blue color completely disappears, indicating the endpoint.

- Calculation: The amount of oxidizing agent is calculated based on the thiosulfate used and the known stoichiometry of its reaction with iodide.

The experimental workflow for a generalized redox titration is outlined below:

Advanced Applications and Automation

Modern redox titrimetry increasingly incorporates automation and computational tools to enhance precision and efficiency. Recent research demonstrates the successful application of Python programming for automating potentiometric redox titrations, specifically for ferrous ion detection with potassium permanganate [4]. This approach utilizes Python libraries such as NumPy for numerical computations and Matplotlib for plotting titration curves, yielding results comparable to conventional instrumental analysis with high accuracy [4].

This integration of artificial intelligence with instrumental chemical analysis represents a significant advancement, particularly for industries requiring high-throughput analysis such as pharmaceutical development and environmental monitoring [4]. Automated systems can monitor potential changes throughout the titration, generating comprehensive datasets for quality control and research purposes.

Redox titrimetry remains an indispensable analytical technique for metal ion determination, combining well-established theoretical principles with practical adaptability. The protocols detailed herein, particularly for ferrous ion quantification and iodometric analyses, provide robust frameworks applicable across diverse research contexts. The ongoing integration of computational tools and automation, as exemplified by Python-based potentiometric systems, further enhances the method's precision, efficiency, and accessibility. As redox titration protocols continue to evolve, they maintain critical importance in advancing analytical capabilities for metal ion research, supporting innovation across scientific and industrial disciplines.

The quantitative analysis of chlorine water in the late 18th century represents a seminal moment in analytical chemistry, establishing the foundational principles of redox titration for metal ion determination. This initial application, developed by Claude Berthollet in 1787, utilized the oxidizing power of chlorine to oxidize indigo, a dye that becomes colorless in its oxidized state, providing a visible endpoint for the titration [5]. This protocol was later adapted by Joseph Gay-Lussac in 1814 for determining chlorine in bleaching powder [5]. These early methods laid the essential groundwork for the development of sophisticated modern titration protocols used for quantifying metal ions such as iron, which are critical in pharmaceutical development, material science, and environmental monitoring. This application note details the historical context and provides detailed, reproducible protocols that bridge this historical innovation with contemporary analytical applications.

Historical Development and Chemical Principles

The First Redox Titrations

The earliest redox titrations capitalized on the strong oxidizing potential of chlorine. Berthollet's method involved titrating chlorine water against a solution of indigo. The fundamental redox reaction involved the decolorization of indigo, providing a clear and visually observable endpoint that signaled the completion of the reaction [5]. This was a pioneering example of using a chemical reaction's inherent property to determine an unknown concentration.

Evolution of Titrants and Indicators

The scope of redox titrimetry expanded significantly in the mid-1800s with the introduction of new oxidizing titrants like permanganate (MnO₄⁻), dichromate (Cr₂O₇²⁻), and iodine (I₂), alongside reducing titrants such as iron(II) (Fe²⁺) and thiosulfate (S₂O₃²⁻) [5]. A major challenge was the lack of suitable indicators. While intensely colored titrants like MnO₄⁻ could serve as their own indicators, the development of the first specific redox indicator, diphenylamine, in the 1920s greatly broadened the applicability of these methods [5].

Key Redox Reaction in Metal Ion Determination

A classic and enduring redox reaction in metal analysis is the titration of iron(II) with permanganate. The balanced equation for this reaction is:

MnO₄⁻ + 5Fe²⁺ + 8H⁺ → Mn²⁺ + 5Fe³⁺ + 4H₂O [6]

In this reaction, MnO₄⁻ (oxidizing agent) is reduced from +7 to +2, while Fe²⁺ (reducing agent) is oxidized from +2 to +3. The deep purple color of permanganate disappearing to form the nearly colorless Mn²⁺ serves as a self-indicating endpoint [6].

Modern Application Note: Determination of Iron Content via Redox Titration

Experimental Objective

To determine the concentration of iron in an unknown sample using potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) as the titrant in a redox titration, applying the principles established in historical chlorine analysis to a modern quantitative assay.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Specification | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) |

0.02 M Standardized Solution | Oxidizing titrant; reacts stoichiometrically with Fe²⁺. |

| Ferrous Ammonium Sulfate Hexahydrate (FAS) | Fe(NH₄)₂(SO₄)₂•6H₂O, Primary Standard |

High-purity compound for standardizing KMnO₄ solution. |

Dilute Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) |

1-2 M, A.C.S. Grade | Provides the H⁺ ions required for the permanganate-iron reaction. |

| Unknown Iron Sample | Solid salt or solution | Sample for which the iron content is to be determined. |

Detailed Protocol

Part A: Standardization of Potassium Permanganate Solution

Potassium permanganate is not a primary standard and must be standardized against a pure substance like Ferrous Ammonium Sulfate (FAS).

- Sample Preparation: Weigh accurately, by difference, three approximately 1.0 g samples of pure FAS into separate 250 mL conical flasks [6].

- Acidification: Dissolve each sample in about 50 mL of deionized water and add 20 mL of dilute sulfuric acid to each flask [7].

- Titration: Fill a 50 mL burette with the

KMnO₄solution of approximate concentration (e.g., ~0.02 M). Titrate the first FAS sample while swirling the flask constantly. - Endpoint Determination: The endpoint is signaled by the appearance of a persistent faint pink color due to a single excess drop of

KMnO₄[6]. Record the burette reading. - Replication: Repeat the titration with the remaining FAS samples until concordant results (titres agreeing within 0.10 mL) are obtained.

- Calculation: Calculate the exact molarity of the

KMnO₄solution using the mass of FAS and the titration volume, based on the 1:5 mole ratio betweenMnO₄⁻andFe²⁺[6].

Part B: Determination of Iron in an Unknown Sample

- Sample Preparation: Weigh accurately, by difference, three samples of the unknown iron compound into separate 250 mL conical flasks.

- Dissolution and Acidification: Dissolve each sample in deionized water and add 20 mL of dilute sulfuric acid to ensure the solution is sufficiently acidic [6] [7].

- Titration: Titrate each sample with the standardized

KMnO₄solution as described in Part A. - Endpoint Determination: The same faint pink color indicates the endpoint.

Data Analysis and Calculation

The following table summarizes the quantitative data from a sample experiment for determining the percentage of iron in an unknown sample [6].

Table 2: Sample Data for Determination of % Iron in an Unknown

| Sample | Mass of Unknown (g) | Volume of KMnO₄ (mL) |

Moles of KMnO₄ |

Moles of Fe²⁺ |

Mass of Fe (g) | % Fe by Mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown 1 | 1.2352 | 26.01 | 0.0005327 | 0.0026635 | 0.1488 | 12.05% |

| Unknown 2 | 1.2577 | 26.47 | 0.0005422 | 0.0027110 | 0.1514 | 12.04% |

| Unknown 3 | 1.2493 | 26.30 | 0.0005386 | 0.0026930 | 0.1504 | 12.04% |

| Average | 12.04% |

Calculations (for Unknown Sample 1):

- Moles of

KMnO₄= Molarity ofKMnO₄× Volume (L) = 0.02048 M × 0.02601 L = 0.0005327 mol [6] - Moles of

Fe²⁺= Moles ofKMnO₄× 5 = 0.0005327 mol × 5 = 0.0026635 mol [6] - Mass of Fe = Moles of

Fe²⁺× Molar Mass of Fe = 0.0026635 mol × 55.85 g/mol = 0.1488 g - % Fe by Mass = (Mass of Fe / Mass of Unknown) × 100% = (0.1488 g / 1.2352 g) × 100% = 12.05%

Advanced Protocol: Automated Endpoint Detection

Modern applications have evolved from visual detection to automated systems that improve precision and accuracy. A contemporary approach involves using a color sensor and the Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV) color model to detect subtle color changes during titration [8].

Automated Titration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of an automated titration system with visual endpoint detection.

Diagram 1: Automated Titration Logic

Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Protocol

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Peristaltic Pump | Provides automated, precise dispensing of the titrant solution [8]. |

| Color Sensor/CCD Camera | Acts as the detector, capturing real-time images of the titration solution [8]. |

| HSV Color Model Algorithm | Replaces human vision; the Hue (H) and Saturation (S) components are particularly sensitive to subtle color changes during redox reactions, enabling precise endpoint detection [8]. |

| Potassium Dichromate | An alternative oxidizing titrant used in the automated determination of total iron content in ores [8]. |

The journey from Berthollet's simple observation of indigo decolorization by chlorine water to modern automated titration platforms demonstrates the enduring importance of redox chemistry in quantitative analysis. The core principle remains the same: a measurable, stoichiometric redox reaction. However, the methods for endpoint detection have evolved from subjective visual assessment to objective, precise, and highly sensitive instrumental techniques. The protocols detailed herein provide researchers and scientists with a clear pathway from foundational theory to practical application, enabling accurate metal ion determination critical for drug development, quality control, and advanced materials research.

Redox titration represents a cornerstone analytical technique in quantitative chemical analysis, enabling the precise determination of metal ion concentrations through controlled oxidation-reduction reactions. This methodology finds extensive application across pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and industrial quality control, particularly for quantifying metal ions in complex matrices. The fundamental principle relies on the stoichiometric electron transfer between an analyte and a standardized reagent, allowing researchers to determine unknown concentrations with high accuracy and precision. Within this framework, a clear understanding of core components—titrants and titrands—and the governing thermodynamic principles embodied by the Nernst equation is paramount for designing robust analytical protocols [9] [10].

The accuracy of redox titrimetry hinges on the quantitative and rapid reaction between the titrant and titrand, the availability of a distinct endpoint detection method, and the absence of interfering species. This document delineates the key terminology and theoretical foundations essential for implementing redox titration protocols, with a specific focus on metal ion determination in research settings. Subsequent sections will provide detailed experimental methodologies, data presentation formats, and visualization tools to facilitate the adoption of these techniques in scientific research and drug development programs.

Key Terminology and Theoretical Foundations

Core Components of a Redox Titration

A redox titration system is composed of several integral components, each playing a defined role in the analytical process. The precise interaction between these components ensures the accurate determination of the analyte's concentration.

Titrant: The titrant is a standardized solution of known concentration, typically a strong oxidizing or reducing agent, which is delivered incrementally to the analyte solution from a burette [10]. Common oxidizing titrants include potassium permanganate (KMnO₄), potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇), and ceric sulfate (Ce(SO₄)₂). These substances are characterized by their high standard reduction potentials, which drive the oxidation of the analyte. The titrant must be stable, undergo a rapid and stoichiometric reaction with the analyte, and be amenable to facile endpoint detection [11] [10].

Titrand: The titrand is the analyte solution containing the species of unknown concentration, which undergoes a change in oxidation state during the titration [9]. In the context of metal ion determination, common titrands include solutions containing iron(II) (Fe²⁺), copper(II) (Cu²⁺), or other transition metal ions. The titrand is typically prepared in a solvent medium that promotes reaction kinetics and stability, often an aqueous solution with controlled pH or acidity [12] [10].

Stoichiometry and Electron Transfer: The reaction between the titrant and titrand involves the transfer of one or more electrons. The balanced redox equation defines the stoichiometric relationship, which is essential for calculating the unknown concentration from the volume of titrant consumed at the equivalence point. For instance, in the titration of Fe²⁺ with permanganate (MnO₄⁻) in acidic medium, the balanced reaction is: [ \ce{MnO4^- + 5Fe^{2+} + 8H+ -> Mn^{2+} + 5Fe^{3+} + 4H2O} ] This equation shows that one mole of MnO₄⁻ reacts with five moles of Fe²⁺, a critical ratio for accurate calculation [12] [10].

The table below summarizes common titrants and associated titrands in redox protocols for metal ion analysis.

Table 1: Common Redox Titrants and Associated Titrands in Metal Ion Analysis

| Titrant | Titrand (Metal Ion) | Reaction Medium | Key Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | Iron(II) (Fe²⁺) [12] | Acidic (e.g., H₂SO₄) | (\ce{MnO4^- + 5Fe^{2+} + 8H+ -> Mn^{2+} + 5Fe^{3+} + 4H2O}) |

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Iron(II) (Fe²⁺) [13] | Acidic | (\ce{Cr2O7^{2-} + 6Fe^{2+} + 14H+ -> 2Cr^{3+} + 6Fe^{3+} + 7H2O}) |

| Ceric Sulfate (Ce(SO₄)₂) | Iron(II) (Fe²⁺) [10] | Acidic | (\ce{Ce^{4+} + Fe^{2+} -> Ce^{3+} + Fe^{3+}}) |

| Iodine (I₂) | Arsenic(III) (As³⁺) [10] | Neutral / Weakly Alkaline | (\ce{AsO3^{3-} + I2 + H2O -> AsO4^{3-} + 2I- + 2H+}) |

The Nernst Equation in Redox Titrations

The Nernst equation provides the fundamental link between the measured electrochemical potential of a solution and the concentrations of the species involved in the redox equilibrium. It is indispensable for understanding the shape of the titration curve and the behavior of the system under non-standard conditions [9] [14] [15].

Mathematical Formulation: For a general reduction half-reaction: [ \ce{Ox + n e^- -> Red} ] the Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E = E^\circ - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{[Red]}{[Ox]} ] where (E) is the electrode potential under non-standard conditions, (E^\circ) is the standard electrode potential, (R) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K), (T) is the temperature in Kelvin, (n) is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction, (F) is the Faraday constant (96485 C/mol), and (\frac{[Red]}{[Ox]}) represents the ratio of the activities of the reduced and oxidized species [14] [15]. At 298 K (25°C), this equation simplifies to: [ E = E^\circ - \frac{0.05916}{n} \log \frac{[Red]}{[Ox]} ]

Application to Titration Curves: During a redox titration, the solution potential is monitored relative to the volume of titrant added. The Nernst equation is applied to the dominant redox couple in solution to calculate the potential at any point [9]:

- Before the equivalence point, the potential is calculated using the Nernst equation for the titrand's half-reaction, as its oxidized and reduced forms are both present in significant quantities.

- After the equivalence point, the potential is calculated using the Nernst equation for the titrant's half-reaction, which now has both its oxidized and reduced forms present [9]. This application results in the characteristic sigmoidal titration curve, with a sharp potential change occurring at the equivalence point.

Significance in Endpoint Detection and Prediction: The magnitude of the potential jump at the equivalence point is directly influenced by the number of electrons transferred ((n)) and the difference in standard potentials ((\Delta E^\circ)) between the two half-reactions. A larger (\Delta E^\circ) results in a more pronounced inflection, enabling more accurate endpoint detection, either visually using indicators or instrumentally via potentiometry [9] [10]. The Nernst equation allows researchers to predict the feasibility and sharpness of a titration for a given analyte-titrant pair.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and the role of the Nernst equation in a redox titration system.

Experimental Protocols: Metal Ion Determination by Redox Titration

Protocol 1: Determination of Iron by Potassium Permanganate Titration

This classic method is widely employed for the quantitative assessment of iron content in various samples, including ores, pharmaceuticals, and industrial products [12].

Principle

In a strongly acidic medium, potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) serves as a powerful oxidizing titrant, quantitatively converting iron(II) (Fe²⁺) to iron(III) (Fe³⁺). The half-reactions and the overall balanced equation are: [ \ce{MnO4^- + 8H+ + 5e^- -> Mn^{2+} + 4H2O} \quad (E^\circ = +1.51\text{ V}) ] [ \ce{Fe^{2+} -> Fe^{3+} + e^-} \quad (E^\circ = +0.77\text{ V}) ] Overall: [ \ce{MnO4^- + 5Fe^{2+} + 8H+ -> Mn^{2+} + 5Fe^{3+} + 4H2O} ] The large positive standard cell potential ((E^\circ_{\text{cell}} = 0.74\text{ V})) confirms the reaction's spontaneity and completeness. The endpoint is signaled by the first persistent faint pink color due to a slight excess of permanganate ion, which acts as a self-indicator [12] [10].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Iron Determination Protocol

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | Standardized titrant solution (~0.02 M). Primary oxidizing agent [12]. |

| Iron(II) Unknown Sample | Prepared solution containing Fe²⁺ ions. The analyte (titrand) of unknown concentration. |

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | ~1 M solution. Provides the strongly acidic medium required for the reaction [12]. |

| Phosphoric Acid (H₃PO₄) | Optional. Added to complex Fe³⁺ product, preventing its yellow color from interfering with the endpoint and lowering the formal potential of the Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ couple. |

| Burette (Class A) | Precision volumetric glassware for accurate delivery of titrant. |

| Potentiometer (Optional) | Consisting of a Pt indicator electrode and a reference electrode (e.g., SCE). For instrumental endpoint detection. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation: Accurately pipette a known volume (e.g., 25.00 mL) of the iron(II) unknown solution into a clean 250 mL conical flask (titration flask) [12].

Acidification: Add approximately 20 mL of 1 M sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) to the flask. The solution must be strongly acidic to prevent the precipitation of iron hydroxides and to ensure the correct reduction of permanganate to Mn²⁺ [12].

Titration Setup: Fill a clean burette with the standardized potassium permanganate solution. Record the initial burette reading.

Titration Execution: Titrate the acidified iron solution with constant swirling. Initially, the purple color of permanganate will decolorize rapidly upon addition. As the titration progresses, the decolorization will slow down.

Endpoint Determination: Continue the titration dropwise until the first permanent faint pink color persists for at least 30 seconds. This color change indicates that all the Fe²⁺ has been oxidized and a slight excess of KMnO₄ is present. Record the final burette reading.

Potentiometric Detection (Alternative): For greater accuracy or colored solutions, use a potentiometric setup. Plot the potential (mV) of a Pt indicator electrode against the volume of titrant added. The equivalence point is identified as the point of maximum slope (inflection point) on the sigmoidal curve [9] [13].

Calculation: The concentration of iron in the unknown solution is calculated using the stoichiometry of the balanced equation. [ C{\ce{Fe}} = \frac{5 \times C{\ce{MnO4-}} \times V{\ce{MnO4-}}}{V{\text{sample}}} ] Where (C) is concentration and (V) is volume.

The workflow for this protocol, including the critical decision points, is summarized in the following diagram.

Advanced Application: Coulometric Titration for Calibration-Free Analysis

Coulometric titration represents a sophisticated approach where the titrant is generated electrochemically in situ, with the quantity calculated directly from Faraday's law, eliminating the need for standardized solutions [16].

Principle

A constant current is applied across an ion-selective polymeric membrane, resulting in the controlled release (e.g., of Ca²⁺ or Ba²⁺ ions) into the sample solution [16]. The amount of substance released ((N)) is given by: [ N = \frac{Q}{nF} = \frac{I \times t}{nF} ] where (I) is the current (amperes), (t) is the time (seconds), (n) is the number of electrons transferred per ion, and (F) is the Faraday constant. The released ions then act as a titrant for an analyte in the sample (e.g., Ba²⁺ for sulfate determination). The endpoint is detected potentiometrically using a corresponding ion-selective electrode [16]. This method is highly accurate and is particularly useful for micro-titrations and automated systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful execution of redox titration protocols requires access to specific reagents and instrumentation. The following toolkit details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Redox Titration

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oxidizing Titrants | Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄), Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇), Ceric Sulfate, Iodine (I₂) [10] | Standardized solutions used as the primary titrants for reducing analytes. KMnO₄ is a self-indicator. K₂Cr₂O₇ is more stable and used with a redox indicator (e.g., diphenylamine) [10]. |

| Reducing Titrants | Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃), Iron(II) Ammonium Sulfate (Mohr's Salt) [10] | Standardized solutions used as primary titrants for oxidizing analytes. Sodium thiosulfate is central to iodometric titrations [10]. |

| Analytes (Titrands) | Iron(II) salts, Copper(II) salts, Hydrogen Peroxide, Dissolved Oxygen [12] [10] | The target metal ion or species of unknown concentration. Must be redox-active. Sample preparation often involves dissolution and reduction to a specific oxidation state. |

| Acidifying Agents | Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄), Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | To provide the acidic medium necessary for many redox reactions (e.g., permanganate, dichromate titrations). H₂SO₄ is preferred over HCl with KMnO₄ to avoid oxidation of Cl⁻ [12]. |

| Complexing Agents | Phosphoric Acid (H₃PO₄) | Used to mask interfering colored products. H₃PO₄ complexes with Fe³⁺ to form a colorless complex, improving endpoint visibility [12]. |

| Redox Indicators | Ferroin, Diphenylamine, Diphenylbenzidine [9] [13] | Compounds that change color at a specific solution potential. Used when the titrant is not self-indicating (e.g., in dichromate titrations). Ferroin changes from red to pale blue at ~1.06 V [10]. |

| Instrumentation | Burette & Pipette (Class A), Potentiometer, Platinum Indicator Electrode, Reference Electrode (e.g., SCE) [9] [13] | Burettes/pipettes enable precise volume measurement. Potentiometric setup allows for instrumental endpoint detection, which is crucial for colored/turbid solutions or when a sharp visual endpoint is absent. |

The rigorous application of redox titration for metal ion determination is underpinned by a clear understanding of its core terminology—the roles of the titrant and titrand—and the governing principles of the Nernst equation. This document has outlined the theoretical framework and provided a detailed, actionable protocol for a fundamental assay like the determination of iron, while also introducing advanced concepts such as calibration-free coulometric titration.

The provided tools, including standardized data tables and workflow visualizations, are designed to enhance reproducibility and clarity in research documentation. Mastery of these concepts and techniques equips researchers and drug development professionals with a reliable and versatile analytical method applicable to a wide range of quantitative challenges, from pharmaceutical quality control to environmental and materials science. The integration of potentiometric endpoint detection with the theoretical predictions of the Nernst equation represents the gold standard for achieving high precision and accuracy in these analyses.

Redox titration is an indispensable technique in analytical chemistry for determining the concentration of an unknown substance by leveraging electron transfer reactions between the analyte and a standard titrant solution [17]. Within the broader scope of metal ion determination research, the selection of an appropriate oxidizing or reducing titrant is critical for achieving accurate and reproducible results. This article details the application notes and experimental protocols for three principal redox titrants: permanganate, dichromate, and iodine. These reagents are foundational in quantitative analysis, particularly for quantifying metal ions such as iron, and are characterized by their distinct reaction chemistries, optimal working conditions, and endpoint detection methods [18] [19]. Mastery of these titrants enables precise analysis across pharmaceutical, environmental, and industrial matrices.

Titrant Profiles and Comparative Analysis

The effective application of redox titrants requires a deep understanding of their intrinsic properties, reactive behaviors, and specific advantages in metal ion determination. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the three featured titrants for easy comparison.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Common Redox Titrants

| Titrant | Chemical Formula | Primary Role | Typical Analytic (e.g., Metal Ions) | Reaction Medium | Endpoint Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanganate | KMnO₄ [18] | Strong oxidizing agent [18] [20] | Fe²⁺, Oxalic acid, H₂O₂ [18] [19] | Acidic (e.g., H₂SO₄) [18] | Self-indicator (colorless to pink) [17] [18] |

| Dichromate | K₂Cr₂O₇ [18] | Strong oxidizing agent [18] [20] | Fe²⁺ [18] | Acidic (e.g., H₂SO₄) [18] | Requires indicator (e.g., Diphenylamine) [18] |

| Iodine | I₂ [18] [21] | Oxidizing agent [18] | Reducing agents (via Iodometry) [18] | Neutral or Weakly Acidic [18] [21] | Starch indicator (blue to colorless) [18] [21] |

Permanganate (KMnO₄)

Potassium permanganate is a powerful and versatile oxidizing titrant. Its most notable feature is its role as a self-indicator; the intense purple MnO₄⁻ ion is reduced to the nearly colorless Mn²⁺ ion, producing a persistent pale pink color at the endpoint [17] [18]. It is commonly deployed in a highly acidic medium, typically using dilute sulfuric acid [18]. Hydrochloric acid is avoided as it can lead to unwanted side reactions with the permanganate ion [18]. A classic application in metal ion analysis is the determination of ferrous iron (Fe²⁺), where the reaction proceeds as follows [19]:

[ 5Fe^{2+} + MnO4^- + 8H^+ \rightarrow 5Fe^{3+} + Mn^{2+} + 4H2O ]

Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇)

Potassium dichromate serves as a strong and stable oxidizing agent. Unlike permanganate, it is not a self-indicator and requires an external redox indicator such as diphenylamine or N-phenylanthranilic acid to signal the endpoint via a sharp color change [18]. It functions effectively in an acidic medium [18]. Its high stability in solution makes it a reliable titrant, primarily used for the determination of ferrous ions. The corresponding redox reaction is [18]:

[ 6Fe^{2+} + Cr2O7^{2-} + 14H^+ \rightarrow 6Fe^{3+} + 2Cr^{3+} + 7H_2O ]

Iodine (I₂)

Iodine solutions function as mild oxidizing agents in two primary titration modalities: iodimetry and iodometry [18] [20]. Iodimetry involves the direct titration of reducing agents with a standard iodine solution. In contrast, iodometry is an indirect method used for analyzing oxidizing agents; the oxidant is reacted with excess iodide (I⁻) to liberate iodine, which is then titrated with a standard thiosulfate solution [18]. The endpoint is typically detected using a starch indicator, which forms an intense blue-black complex with iodine that disappears at the endpoint [18] [21]. The core reaction with the titrant thiosulfate is [19]:

[ I2 + 2S2O3^{2-} \rightarrow S4O_6^{2-} + 2I^- ]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of Fe²⁺ by KMnO₄ Titration

This protocol outlines the quantitative determination of ferrous iron concentration in an acidic aqueous solution using potassium permanganate as the titrant [17].

Principle

Ferrous ions (Fe²⁺) in an acidic medium are quantitatively oxidized to ferric ions (Fe³⁺) by permanganate ions (MnO₄⁻), which are simultaneously reduced to manganese ions (Mn²⁺). The faint pink color of the excess permanganate ion after the complete oxidation of all Fe²⁺ serves as the endpoint [17] [18].

Workflow

Materials and Reagents

- Burette [20]

- Standard KMnO₄ solution (known concentration)

- Analyte solution containing Fe²⁺

- Dilute Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) (~1 M) [18]

- Conical flask

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Transfer a known precise volume (e.g., 20.00 mL measured by pipette) of the Fe²⁺ analyte solution into a clean conical flask [20].

- Acidification: Acidify the solution by adding approximately 20 mL of dilute sulfuric acid. This provides the necessary H⁺ ions for the reaction [18].

- Titration Setup: Fill a clean burette with the standardized potassium permanganate solution. Record the initial burette reading.

- Titration: Slowly add the KMnO₄ solution from the burette to the analyte solution in the flask while constantly swirling. Initially, the purple color of the permanganate will decolorize upon contact.

- Endpoint Detection: Continue the titration until a faint pale pink color persists for at least 30 seconds in the solution. This signals that all Fe²⁺ has been oxidized and a slight excess of KMnO₄ is present [17] [18].

- Recording: Record the final burette reading. The volume of KMnO₄ used is the difference between the final and initial readings.

Calculations

The concentration of Fe²⁺ in the original solution is calculated based on the stoichiometry of the reaction, where 1 mole of MnO₄⁻ reacts with 5 moles of Fe²⁺ [19].

[ C{Fe^{2+}} = \frac{5 \times C{KMnO4} \times V{KMnO4}}{V{Analyte}} ] Where:

- ( C_{Fe^{2+}} ): Concentration of Fe²⁺ (mol/L)

- ( C{KMnO4} ): Concentration of KMnO₄ solution (mol/L)

- ( V{KMnO4} ): Volume of KMnO₄ solution used (L)

- ( V_{Analyte} ): Volume of analyte solution taken (L)

Protocol: Determination of an Oxidizing Agent by Iodometric Titration

This protocol describes an indirect method (iodometry) for determining the concentration of an oxidizing agent (e.g., K₂Cr₂O₇) by liberating iodine and titrating with sodium thiosulfate [18].

Principle

A known amount of an oxidizing agent is reacted with an excess of potassium iodide (KI) in an acidic medium. The oxidizing agent liberates an equivalent amount of iodine (I₂). The liberated iodine is then titrated with a standardized sodium thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) solution. Starch is used as an indicator, producing a blue complex that disappears at the endpoint when all I₂ is reduced to I⁻ [18] [21].

Workflow

Materials and Reagents

- Burette [20]

- Standard Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) solution

- Potassium Iodide (KI) solution (in excess) [18] [21]

- Oxidizing agent solution (e.g., K₂Cr₂O₇ of unknown concentration)

- Dilute Acid (e.g., HCl or H₂SO₄) [21]

- Starch indicator solution [18] [21]

- Iodine flask or conical flask

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Liberation of Iodine: Pipette a known volume of the oxidizing agent solution into an iodine flask. Add a significant excess of KI solution (e.g., 10-20 mL), followed by gentle acidification with a small volume of dilute acid. Swirl to mix and allow the mixture to stand in the dark for a few minutes for complete reaction and I₂ liberation [21].

- Initial Titration: Titrate the liberated iodine with the standardized sodium thiosulfate solution. Add the thiosulfate steadily with continuous swirling until the solution turns a pale yellow.

- Indicator Addition: Add 1-2 mL of freshly prepared starch solution. The formation of a deep blue starch-iodine complex will be observed [21].

- Final Titration: Continue adding the thiosulfate solution dropwise, swirling vigorously after each drop, until the blue color completely disappears, and the solution becomes colorless.

- Recording: Record the total volume of sodium thiosulfate solution used.

Calculations

The calculation is based on the stoichiometry that 1 mole of I₂ reacts with 2 moles of S₂O₃²⁻. The amount of the original oxidizing agent is then back-calculated from the amount of I₂ it produced.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of redox titration protocols depends on the preparation and use of specific reagent solutions. The following table lists key materials and their critical functions in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Redox Titration Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Critical Notes for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Standard KMnO₄ Solution | Primary oxidizing titrant for direct titration of Fe²⁺ and other reducing agents [18]. | Requires standardization; stable over long periods if stored properly. Acts as a self-indicator [18]. |

| Standard Na₂S₂O₃ Solution | Reducing titrant used in iodometric titrations to quantify liberated I₂ [18]. | Requires standardization; can be unstable over time and should be restandardized periodically. |

| Starch Indicator Solution | Forms an intense blue complex with I₂, used for clear endpoint detection in iodine-based titrations [18] [21]. | Should be added near the endpoint (when solution is pale yellow) to prevent decomposition of the complex [21]. |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | Source of I⁻ ions; used in excess to liberate I₂ from oxidizing agents in iodometry [18] [21]. | Ensures the quantitative release of I₂. The solution should be colorless and free from iodate. |

| Diphenylamine Indicator | Redox indicator used for titrations with K₂Cr₂O₇, where no self-indicator is available [18]. | Shows a color change from bluish-green or purple to blue-violet at the endpoint [18]. |

| Dilute Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | Provides the acidic medium required for permanganate and dichromate titrations [18]. | Preferred over HCl for KMnO₄ titrations to avoid chlorine gas formation [18]. |

In analytical chemistry, redox titrations are a fundamental technique for determining the concentration of unknown metal ions in a solution. Unlike acid-base titrations that monitor pH changes, redox titration curves illustrate the change in electrochemical potential as a function of the titrant volume added. The potential, measured in volts (V), reflects the ratio of oxidized to reduced species throughout the titration process, providing critical information about the reaction progress and equivalence point [5] [1]. The development of redox titrimetry dates back to 1787 when Claude Berthollet introduced a method for analyzing chlorine water based on its ability to oxidize indigo [5]. The method gained broader applicability in the mid-1800s with the introduction of common titrants like MnO₄⁻, Cr₂O₇²⁻, and I₂ as oxidizing agents, and Fe²⁺ and S₂O₃²⁻ as reducing agents [5] [1].

For researchers in drug development and metal ion analysis, understanding the theoretical underpinnings of these curves is essential for method development, validation, and accurate quantification of metal catalysts or impurities in pharmaceutical compounds.

Theoretical Foundation and Mathematical Formalism

The shape of a redox titration curve is governed by the Nernst equation, which relates the electrochemical potential of a half-reaction to the concentrations of the participating species [5] [1]. For a generalized redox titration where a reduced titrand ((A{red})) reacts with an oxidized titrant ((B{ox})): [ A{red} + B{ox} \rightleftharpoons B{red} + A{ox} ] The reaction potential ((E{rxn})) is the difference between the reduction potentials of the two half-cells [5] [1]: [ E{rxn} = E{B{ox}/B{red}} - E{A{ox}/A{red}} ] At equilibrium, after each titrant addition, the potential is zero, making the reduction potentials of the titrand and titrant identical. This allows the use of either half-reaction to monitor the titration's progress [5] [1].

The potential at any point in the titration is calculated using the Nernst equation. Before the equivalence point, the solution contains significant quantities of both the oxidized and reduced forms of the titrand, making its half-reaction the most convenient for calculation [5] [1]: [ E = E{A{ox}/A{red}}^{\circ} - \frac{RT}{nF}\ln{\frac{[A{red}]}{[A{ox}]}} ] After the equivalence point, the potential is more easily calculated using the titrant's half-reaction, as excess titrant is present [5] [1]: [ E = E{B{ox}/B{red}}^{\circ} - \frac{RT}{nF}\ln{\frac{[B{red}]}{[B{ox}]}} ] It is critical to note that a formal potential, which is matrix-dependent, is often used in place of the standard state potential in these calculations to account for the specific experimental conditions such as ionic strength and pH [5] [1]. The precise calculation of titration curves must also account for the reaction deficiency (incompleteness of the reaction), an factor analogous to salt hydrolysis in acid-base titrations [22].

Calculation Methodology and Data Presentation

The following table outlines the systematic approach for calculating potential values across the three key regions of a redox titration curve, using the titration of Fe²⁺ with Ce⁴⁺ as a canonical example.

Table 1: Methodology for Calculating Redox Titration Curve Data

| Titration Region | Governing Equation | Calculation Example for 50.0 mL of 0.100 M Fe²⁺ with 0.100 M Ce⁴⁺ |

|---|---|---|

| Before Equivalence Point (e.g., 20 mL Titrant) | Use Nernst equation for analyte (Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺). (E = E^{\circ}'_{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+}} - \frac{0.05916}{1}\log\frac{[Fe^{2+}]}{[Fe^{3+}]}) | Moles Fe²⁺ initial = 5.00 mmol Moles Ce⁴⁺ added = 2.00 mmol Moles Fe²⁺ remaining = 3.00 mmol Total Volume = 70.0 mL (E = 0.767 - 0.05916\log(\frac{3.00/70.0}{2.00/70.0}) = 0.771 V) |

| At Equivalence Point (50 mL Titrant) | Potentials of both couples are equal. (E{eq} = \frac{n{Fe}E^{\circ}'{Fe} + n{Ce}E^{\circ}'{Ce}}{n{Fe} + n_{Ce}}) | (E_{eq} = \frac{(1 \times 0.767 V) + (1 \times 1.70 V)}{1 + 1} = 1.23 V) |

| After Equivalence Point (e.g., 70 mL Titrant) | Use Nernst equation for titrant (Ce⁴⁺/Ce³⁺). (E = E^{\circ}'_{Ce^{4+}/Ce^{3+}} - \frac{0.05916}{1}\log\frac{[Ce^{3+}]}{[Ce^{4+}]}) | Moles Ce³⁺ = 5.00 mmol Moles Ce⁴⁺ excess = 2.00 mmol Total Volume = 120.0 mL (E = 1.70 - 0.05916\log(\frac{5.00/120.0}{2.00/120.0}) = 1.73 V) |

Note: The values for standard formal potentials ((E^{\circ}')) are illustrative. Values at 25°C and in 1 M H₂SO₄ are often used: (E^{\circ}'_{Ce^{4+}/Ce^{3+}} \approx 1.44 V) and (E^{\circ}'_{Fe^{3+}/Fe^{2+}} \approx 0.68 V), which would yield a different equivalence point potential.

The equivalence volume ((V{eq})) is a critical parameter calculated using the principle of stoichiometry [23]: [ M{analyte} \times V{analyte} = M{titrant} \times V{eq} ] For the example above, (0.100 \text{ M} \times 50.0 \text{ mL} = 0.100 \text{ M} \times V{eq}), thus (V_{eq} = 50.0 \text{ mL}) [23]. A rigorous calculation must make allowance for the reaction deficiency, as the equilibrium constant dictates how "complete" the reaction is at any given point [22].

Experimental Protocol: Determination of Iron via Redox Titration

This protocol details the precise determination of Fe²⁺ concentration using a standardized cerium(IV) solution, a common assay in pharmaceutical and metallurgical analysis.

Materials and Equipment

- Titrant: 0.1 N Cerium(IV) sulfate in 1 M H₂SO₄

- Analyte Solution: Unknown concentration of Fe²⁺ (e.g., from a dissolved drug substance or metal alloy) in 1 M H₂SO₄.

- Indicator: 1,10-Phenanthroline ferrous complex (Ferrion) or potentiometric detection.

- Equipment: Potentiometer with Platinum Indicator Electrode and Calomel/Saturated Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode, 50 mL burette, magnetic stirrer, analytical balance.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Standardization of Titrant (if necessary): Standardize the cerium(IV) titrant against a primary standard such as arsenious trioxide (As₂O₃) or sodium oxalate (Na₂C₂O₄) to determine its exact normality.

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh the sample containing the unknown Fe²⁺ and transfer it quantitatively into a 250 mL titration vessel. Dissolve in 1 M H₂SO₄ and dilute to approximately 100 mL with the same acid.

- Instrument Setup: Place the titration vessel on a magnetic stirrer. Immerse the platinum and reference electrodes into the solution, ensuring they are properly connected to the potentiometer.

- Titration and Data Logging:

- Begin stirring the solution at a constant rate to ensure homogeneity without introducing air.

- Record the initial potential reading (mV or V).

- Add the titrant in small, incremental volumes (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mL). After each addition, allow the potential to stabilize and record both the cumulative titrant volume and the corresponding stable potential.

- As the rate of potential change increases (indicating the approach of the equivalence point), reduce the titrant increments to 0.1-0.2 mL.

- Continue adding titrant until well past the equivalence point, as indicated by a reversal in the rate of potential change.

- Endpoint Determination: Plot the measured potential (E) against the volume of titrant added. The equivalence point volume is identified as the center of the steepest, nearly vertical portion of the sigmoidal curve. This can be precisely determined by calculating the first derivative (ΔE/ΔV) and finding the volume at the maximum.

Conceptual Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The process of calculating and interpreting a redox titration curve can be visualized as a logical pathway where experimental data and theoretical equations are integrated. The following diagram maps this workflow, from initial setup to final result.

Diagram 1: Logical workflow for calculating a redox titration curve, showing the decision points based on titrant volume relative to the equivalence point.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The accuracy and success of a redox titration depend heavily on the careful selection of titrants and indicators. The table below catalogues essential reagents used in these analyses.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Redox Titration of Metal Ions

| Reagent Solution | Chemical Composition | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cerium(IV) Sulfate | Ce(SO₄)₂ in H₂SO₄ | Strong oxidizing titrant. Preferred over KMnO₄ for its stability, reproducibility, and use in HCl media. Used for Fe²⁺, As(III) determination [5]. |

| Potassium Permanganate | KMnO₄ in H₂O | Strong, self-indicating oxidizing titrant (purple to colorless). Used for Fe²⁺, H₂O₂, and oxalate analysis. Requires specific acidic conditions [5] [1]. |

| Potassium Dichromate | K₂Cr₂O₇ in H₂O | Strong oxidizing titrant. Requires a redox indicator (e.g., diphenylamine). Advantage is its primary standard quality [5] [1]. |

| Iodine Solution | I₂ in KI | Mild oxidizing titrant. Used for the determination of strong reducing agents like As(III) and S₂O₃²⁻ (thiosulfate) [5] [1]. |

| Sodium Thiosulfate | Na₂S₂O₃ in H₂O | Common reducing titrant. Primarily used in iodometric titrations to titrate iodine liberated from redox reactions [5] [1]. |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline (Ferrion) | C₁₂H₈N₂ in H₂O | Redox indicator. Its ferrous complex is red, and its ferric complex is pale blue. Sharp color change at specific potentials [5]. |

| Diphenylamine | (C₆H₅)₂NH in H₂O | Redox indicator. Colorless in reduced state, violet in oxidized state. Commonly used in dichromate titrations of Fe²⁺ [5] [1]. |

The precise calculation of redox titration curves and reaction potentials is indispensable for developing robust analytical methods in metal ion determination. Mastery of the Nernst equation's application across different titration regions, combined with a rigorous experimental protocol that accounts for factors like reaction completeness, allows researchers to accurately locate the equivalence point and determine analyte concentration with high precision [5] [22]. The integration of potentiometric detection with the theoretical framework provides a powerful, selective, and quantitative tool essential for quality control in drug development and metallurgical analysis.

Practical Protocols and Applications: Determining Specific Metal Ions in Research and Industry

Within the broader scope of redox titration protocols for metal ion determination, the quantification of iron stands as a fundamental analytical technique critical to metallurgical, pharmaceutical, and environmental research. This application note delineates detailed standard operating procedures for the determination of total iron content using potassium dichromate titrimetry, as standardized by ASTM E246 [24] [25]. While potassium permanganate offers an alternative titrant, its application can be limited by susceptibility to interference from organic matrices and chloride ions [26]. Potassium dichromate serves as a superior oxidizing agent in many contexts due to its stability and sharp endpoint determination. The procedures herein are designed to ensure high precision, with modern adaptations incorporating automated visual endpoint detection to enhance reproducibility and accuracy beyond traditional manual methods [8].

Principles and Theoretical Background

The determination of iron relies on the principle of redox titration, wherein all iron in the sample is reduced to the ferrous state (Fe²⁺) and subsequently titrated with an oxidizing agent. The potassium dichromate method is based on the quantitative oxidation of Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺ in an acidic medium.

The stoichiometric reaction is as follows: Cr₂O₇²⁻ + 6Fe²⁺ + 14H⁺ → 2Cr³⁺ + 6Fe³⁺ + 7H₂O

A critical advantage of dichromate titrimetry is the lack of necessity for an indicator in automated systems; however, for manual titration, redox indicators such as sodium diphenylamine sulfonate are employed. The endpoint is characterized by a distinct color change from green (attributed to Cr³⁺ ions) to a violet or blue hue, depending on the indicator used [8] [25]. For complex matrices, particularly carbon-containing iron ores, sample pre-treatment using perchloric acid-assisted digestion is essential to eliminate organic carbon interference, which would otherwise result in cloudy solutions and inaccurate endpoints [27].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table catalogues the essential reagents and materials required for the successful execution of iron determination via potassium dichromate titration.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Iron Determination by Dichromate Titrimetry

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Primary Standard Titrant | Oxidizes Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺; prepare standardized solution [25]. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) or Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | Sample Dissolution Medium | Dissolves iron ores and related materials [25]. |

| Stannous Chloride (SnCl₂) | Reducing Agent | Reduces Fe³⁺ to Fe²�+ prior to titration (Test Method B of ASTM E246) [24] [25]. |

| Titanium(III) Chloride (TiCl₃) | Reducing Agent | Used in conjunction with SnCl₂ for complete reduction [8] [27]. |

| Sodium Tungstate (Na₂WO₄) | Indicator Precursor | Forms tungsten blue to signal initial reduction stage [8]. |

| Sulfur-Phosphoric Acid Mixture | Complexing Agent | Complexes Fe³⁺ to stabilize the solution and sharpen the endpoint. |

| Perchloric Acid (HClO₄) | Digestive Reagent | Removes carbon from carbon-containing iron ores during dissolution [27]. |

| o-Phenanthroline | Indicator (Alternative) | Used in ferrous sulfate titrations; endpoint change to brick red [28]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Digestion

The initial preparation is critical for obtaining a representative and fully dissolved sample.

- Weighing: Accurately weigh approximately 0.2-0.3 g of a homogeneous iron ore sample (dried to constant weight) and transfer it to a 500 mL conical flask [25].

- Acid Dissolution: Add 10-20 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) to the flask. Heat gently on a hot plate until the sample is completely dissolved. For ores resistant to HCl, a mixture of sulfuric and phosphoric acids may be employed.

- Carbon Removal (for carbon-containing ores): If the sample contains carbon (evident by a black or cloudy solution), add 1-2 mL of perchloric acid (HClO₄) drop-wise as white fumes of sulfur trioxide begin to evolve. Continue heating until the solution clears, indicating complete carbon oxidation [27].

- Reduction of Iron: The reduction process converts all iron to the ferrous (Fe²⁺) state, essential for the subsequent titration.

- Stannous Chloride Reduction: Add stannous chloride (SnCl₂) solution drop-wise to the hot solution until the color changes from brown to a light yellow, indicating the reduction of Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺. A slight excess is added, which is later removed [8] [25].

- Cooling and Dilution: Rapidly cool the solution under running water. Transfer it quantitatively to a 250 mL volumetric flask, dilute to the mark with deionized water, and mix thoroughly.

Automated Titration with Visual Endpoint Detection

This protocol leverages a modern automated platform for enhanced precision, utilizing the HSV color model for endpoint determination [8].

- Apparatus Setup: Establish an automated titration platform comprising a color sensor (e.g., an 8-megapixel industrial camera), a programmable peristaltic pump for titrant delivery, and a controlled lighting environment (e.g., an LED backlight guide plate).

- System Calibration: Derive the exact threshold values for Hue (H) and Saturation (S) components of the HSV color model for the specific titration stages through manual pre-calibration. The system is programmed to recognize the color sequence: light yellow → tungsten blue → colorless → blue-green → end point [8].

- Titration Execution:

- Pipette a 50 mL aliquot of the prepared sample solution into the titration vessel.

- Initiate the automated sequence. The peristaltic pump dispenses the standardized potassium dichromate solution.

- The color sensor captures real-time video of the solution. The Hue (H) and Saturation (S) components are continuously analyzed to capture subtle color changes with high sensitivity.

- The titration endpoint is automatically determined by the software when the H and S values cross the pre-defined thresholds, signaling the stoichiometric completion of the reaction.

- Calculation: The iron content is calculated based on the volume and concentration of the potassium dichromate solution consumed, using the established stoichiometry of the redox reaction. The formula for the mass percentage of iron is:

% Fe = (V × M × 55.845 × 100) / (m × 1000)Where:V= Volume of K₂Cr₂O₇ used (mL)M= Molarity of K₂Cr₂O₇ solution (mol/L)m= Mass of the sample (g)

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete automated titration process.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Titration Stages and Color Changes

The titration process involves distinct stages, each marked by a specific color transition, which can be precisely monitored using the HSV color model.

Table 2: Color Changes During the Redox Titration Stages of Iron Ore

| Stage | Process Description | Solution Color Change | Key Chemical Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial Reduction | Addition of SnCl₂ after sample dissolution. | Brown → Light Yellow | Fe³⁺ → Fe²⁺ |

| 2. Final Reduction | Addition of TiCl₃ and Na₂WO₄ solution. | Light Yellow → Tungsten Blue → Colorless | W⁶⁺ → W⁵⁺ (Blue), then W⁵⁺ → W⁶⁺ (Colorless) |

| 3. Titration & Endpoint | Titration with K₂Cr₂O₇. | Colorless → Blue-Green (Endpoint) | Fe²⁺ → Fe³⁺, Cr⁶⁺ → Cr³⁺ (Green) |

Method Performance and Validation

The automated visual detection method demonstrates high accuracy and precision, suitable for rigorous research applications.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Automated Visual Titration for Iron Determination

| Performance Parameter | Result / Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Range | 30% to 95% Fe | Applicable to iron ores, concentrates, and agglomerates [24]. |

| Accuracy (Derivation) | < 1.0% | Determination of a 66.1% standard iron ore sample [8]. |

| Titration Error | < 0.2 mL | Comparable volume error in related machine vision titration [28]. |

| Precision (RSD) | 0.07% - 0.43% | Achieved with perchloric acid digestion for carbon-containing ores [27]. |

| Analysis Time | ~30 minutes | Significant improvement over traditional roasting methods (2-4 hours) [27]. |

Advanced Applications and Methodological Evolution

The paradigm of iron determination is shifting with the integration of advanced computational and sensing technologies. The implementation of the HSV color model represents a significant advancement, as its components of Hue and Saturation demonstrate partial independence, allowing them to collectively capture subtle solution color changes with high sensitivity, surpassing the capabilities of the human eye [8]. Further evolution is evident in the application of deep learning architectures. The ResNet14Attention network, which incorporates residual modules and an attention mechanism, has been documented to achieve 100% training and testing accuracy in identifying the titration endpoint for potassium dichromate, outperforming other convolutional neural networks like VGG and GoogLeNet [29]. These technologies enable dynamic classification of titration speed, dividing the process into multiple stages (e.g., fast, medium, slow, endpoint) to optimize both efficiency and accuracy [28]. For researchers analyzing complex biological matrices, it is imperative to note that direct titration of untreated organic samples (e.g., spinach) is not advisable, as the titrant will oxidize all reducible substances (sugars, oxalates), leading to erroneously high results [26]. Such matrices require prior asking or acid digestion to isolate the inorganic iron content for accurate determination.

Protocol for Antimony and Tin Analysis in Ore and Sample Matrices

Redox titrations are a cornerstone of analytical chemistry for determining the concentration of metal ions in various sample matrices. These methods leverage oxidation-reduction reactions, where the analyte is converted to a single oxidation state and titrated with a suitable oxidizing or reducing agent. The endpoint is determined by a visible color change or potentiometric methods, indicating the reaction's completion. This protocol, framed within broader research on metal ion determination, details standardized methods for the quantitative analysis of antimony and tin in ores and other solid samples, providing researchers and scientists with robust, reproducible experimental workflows.

Theoretical Background

The determination of antimony and tin relies on their redox chemistry in acidic aqueous solutions. Antimony commonly exists in the +3 and +5 oxidation states, while tin is found in the +2 and +4 states. In these protocols, the sample is processed to ensure all antimony is in the Sb³⁺ state and all tin is in the Sn²⁺ state. These reduced species are then titrated with an oxidizing agent.

The key half-reactions involved are:

- For antimony:

Sb⁵⁺ + 2e⁻ → Sb³⁺ - For tin:

Sn⁴⁺ + 2e⁻ → Sn²⁺

The corresponding titration reactions with iodine are:

The equivalence point is marked by the first slight excess of the oxidizing agent, which can be detected visually with starch indicator (which forms a blue complex with iodine) or more precisely through amperometric or potentiometric methods [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential materials and reagents required for the successful execution of these analytical protocols.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) |

Reducing titrant used in standardizing iodine solutions [30]. |

Potassium Iodate (KIO₃) |

Primary standard for preparing and standardizing iodine solutions indirectly. |

| Starch Indicator | Visual endpoint indicator; forms an intense blue complex with triiodide [31]. |

Iodine (I₂) / Triiodide (I₃⁻) |

Oxidizing titrant for determining Sb³⁺ and Sn²⁺ [30] [31]. |

Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) |

Dissolution medium for ores and creates an acidic environment for the redox reaction [30] [32]. |

Potassium Iodide (KI) |

Used to stabilize iodine in solution by forming the more soluble triiodide ion (I₃⁻). |

| Reducing Agent (e.g., Zinc) | Converts all antimony or tin in the sample to a single, reduced oxidation state prior to titration [30]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Antimony Determination

Principle: Antimony in the sample is reduced to the tripositive state (Sb³⁺) and subsequently titrated with a standardized iodine solution, which oxidizes it to the pentavalent state (Sb⁵⁺).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve a 9.62 g sample of the ore (e.g., stibnite) in hot, concentrated HCl(aq) [30] [32].

- Reduction: Pass the dissolved sample over a reducing agent to ensure all antimony is in the

Sb³⁺form [30]. - Titration:

a. Transfer the solution to a titration flask and buffer to approximately pH 8 [31].

b. Add a few drops of freshly prepared starch indicator solution [31] [32].

c. Titrate with a standardized iodine (

I₃⁻) solution until the first permanent blue color appears, indicating the endpoint [30] [31]. - Calculation:

- The molar ratio of

I₃⁻toSb³⁺is 1:3 [30]. - Moles of

Sb³⁺= 3 × (Moles ofI₃⁻used) - Mass of Antimony = Moles of

Sb³⁺× 121.76 g/mol - Percentage of Antimony = (Mass of Antimony / Mass of Sample) × 100%

- The molar ratio of

Protocol for Tin Determination

Principle: Tin in the sample is reduced to the stannous state (Sn²⁺) and titrated with a standardized triiodide solution, which oxidizes it to the stannic state (Sn⁴⁺).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Crush and dissolve a 10.00 g sample of the rock in sulfuric acid [30].

- Reduction: Pass the solution over a reducing agent to ensure all tin is in the

Sn²⁺form [30]. - Titration:

a. Place the solution containing

Sn²⁺in a conical flask. b. Titrate with a standardizedI₃⁻solution (e.g., 0.5560 M NaI₃) until the endpoint is reached [30]. c. The endpoint can be determined visually with starch or via an instrumental method. - Calculation:

- The molar ratio of

I₃⁻toSn²⁺is 1:1 [30]. - Moles of

Sn²⁺= Moles ofI₃⁻used - Mass of Tin = Moles of

Sn²⁺× 118.71 g/mol - Percentage of Tin = (Mass of Tin / Mass of Sample) × 100%

- The molar ratio of

Data Presentation and Analysis

The following table summarizes typical quantitative data obtained from these titration protocols, demonstrating their application for accurate metal quantification.

Table 2: Summary of Quantitative Titration Data for Antimony and Tin

| Analyte | Sample Mass (g) | Titrant & Concentration | Titrant Volume (mL) | Moles of Analyte | Mass of Element (g) | Percentage in Ore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimony [30] | 9.62 | I₂ (Concentration not specified) |

43.70 | 0.01639 mol | 1.995 g | 20.74% |

| Tin [30] | 10.00 | 0.5560 M NaI₃ |

34.60 | 0.01924 mol | 2.284 g | 22.84% |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The logical sequence of the analytical procedure, from sample preparation to final calculation, is outlined in the workflow diagram below.

Figure 1: Redox Titration Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in the analytical protocol for antimony and tin determination.

The core redox "signaling" pathway at the heart of the titration is the electron transfer between the analyte and the titrant.

Figure 2: Core Redox Reaction. This diagram illustrates the fundamental electron transfer processes during the titration.

Within the framework of redox titration protocols for metal ion determination, the principles of oxidation-reduction reactions form the cornerstone of numerous quality control applications across industries. This article details the practical application of these principles in two critical areas: assessing antioxidant activity in food matrices and profiling impurities in pharmaceuticals. The accurate quantification of antioxidants is vital for evaluating food quality and nutritional value, while stringent impurity control is essential for ensuring drug safety and efficacy. The protocols outlined herein, developed for researchers and drug development professionals, leverage advanced analytical techniques including automated visual titration, electrochemical sensing, and high-resolution chromatography to provide robust and reliable measurement methodologies aligned with current regulatory standards [8] [33] [34].

Measuring Antioxidants in Food

Analytical Techniques for Antioxidant Quantification

Antioxidants play a crucial role in mitigating oxidative stress and are essential for preserving food quality and enhancing health. Accurate quantification requires a suite of analytical techniques, each with distinct mechanisms and applications [33].

Table 1: Analytical Methods for Determining Antioxidant Activity

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Detection Mechanism | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Measures current from electron transfer in redox reactions [33] | Rapid analysis, high sensitivity [33] | Instrument complexity, interference from other compounds [33] |

| Spectroscopic | UV-Vis Spectroscopy, Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Mass Spectrometry (MS), FTIR | Absorbance/emission of light by antioxidants; molecular weight and functional group analysis [33] | Rapid, non-destructive; provides molecular insights [33] | Requires sophisticated instrumentation and expertise [33] |

| Chromatographic | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), Gas Chromatography (GC), Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) | Separation followed by detection (e.g., UV, MS) [33] | Reliable separation and precise quantification [33] | Extensive sample preparation, specialized equipment [33] |

| Novel Sensors | Enzyme-based, DNA-based, and Cell-based Biosensors; Electrochemical Nanosensors | Biological recognition or nanomaterial-enhanced signal transduction [33] | High sensitivity and specificity; real-time potential [33] | Biosensors can have low stability; nanosensor synthesis can be complex [33] |

Protocol: Antioxidant Activity Measurement via Electrochemical Nanosensor

This protocol utilizes a nanosensor to leverage the enhanced sensitivity and selectivity provided by nanomaterials for the detection of antioxidants [33].

Experimental Workflow: Antioxidant Nanosensor Analysis

Materials and Reagents

- Nanomaterials: Carbon nanotubes, graphene, or metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver) [33].

- Electrochemical Cell: Consisting of a working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon), a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and a counter electrode (e.g., platinum wire) [33].

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat: Instrument for applying potential and measuring current.

- Buffer Solutions: For maintaining optimal pH during analysis (e.g., phosphate buffer saline).

- Standard Antioxidant Solutions: (e.g., Gallic acid, Trolox, Ascorbic acid) for sensor calibration.

- Food Samples: Homogenized and extracted as required.

Procedure

- Sensor Fabrication: Functionalize the selected nanomaterial with specific ligands to enhance recognition of target antioxidants. Deposit the nanomaterial onto the surface of the working electrode to create the nanosensor [33].

- Sensor Calibration: Prepare a series of standard antioxidant solutions of known concentrations. Perform electrochemical measurements (e.g., DPV) with the calibrated nanosensor and record the current response. Plot a calibration curve of current versus concentration [33].

- Sample Analysis: Prepare the food sample through homogenization and extraction in a suitable solvent. Transfer the extract to the electrochemical cell and perform the measurement under identical conditions as the calibration [33].

- Quantification: Determine the antioxidant concentration in the sample by interpolating the measured current response from the calibration curve [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Antioxidant and Impurity Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Oxidizing titrant for iron content determination via redox titration [8]. |

| Functionalized Nanomaterials | Enhance sensor sensitivity and selectivity for electrochemical antioxidant detection [33]. |

| HPLC-MS Grade Solvents | Used in mobile phases for high-resolution separation and detection of impurities [34] [35]. |

| Stable Free Radicals (DPPH, ABTS) | Used in spectrophotometric assays to determine free radical scavenging activity of antioxidants [36]. |

| ICP-MS Multi-Element Standard Solutions | Used for calibration and quantification of elemental impurities in accordance with ICH Q3D [37]. |

| Nitrosamine Standard Mixtures | Reference standards for accurate identification and quantification of genotoxic impurities [34] [37]. |

Impurity Profiling in Pharmaceuticals

Analytical Techniques for Drug Impurity Profiling

Impurity profiling is a critical component of pharmaceutical quality control, mandated by ICH guidelines (Q3A, Q3B, Q3C, Q3D) to ensure patient safety. It involves the detection, identification, and quantification of impurities that may arise from synthesis, degradation, or interaction with packaging [34] [37].

Table 3: Analytical Techniques for Pharmaceutical Impurity Profiling

| Impurity Type | Common Analytical Techniques | Primary Application and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Impurities | Ultra High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC), LC-MS/MS [34] [35] | Separation and identification of trace-level process-related impurities and degradation products [34]. |

| Elemental Impurities | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [34] [37] | Highly sensitive detection and quantification of metallic catalysts and toxic elements per ICH Q3D [34] [37]. |

| Residual Solvents | Gas Chromatography (GC), GC-MS [34] [37] | Analysis of volatile organic solvents used in manufacturing, as per ICH Q3C [34] [37]. |

| Extractables & Leachables | GC-MS, LC-MS, FTIR [37] | Identification of compounds migrating from packaging or processing materials into the drug product [37]. |

| Genotoxic Impurities (e.g., Nitrosamines) | LC-UHPLC-MS/MS, GC-MS [34] [37] | Sensitive quantification of potent mutagenic impurities at very low (ppm/ppb) levels [34]. |

Protocol: HPLC-MS Analysis of Organic Impurities

This protocol describes the use of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS) for the separation, identification, and quantification of organic impurities in a drug substance.