Redox Titration in Analytical Chemistry: Principles, Methods, and Advanced Applications for Researchers

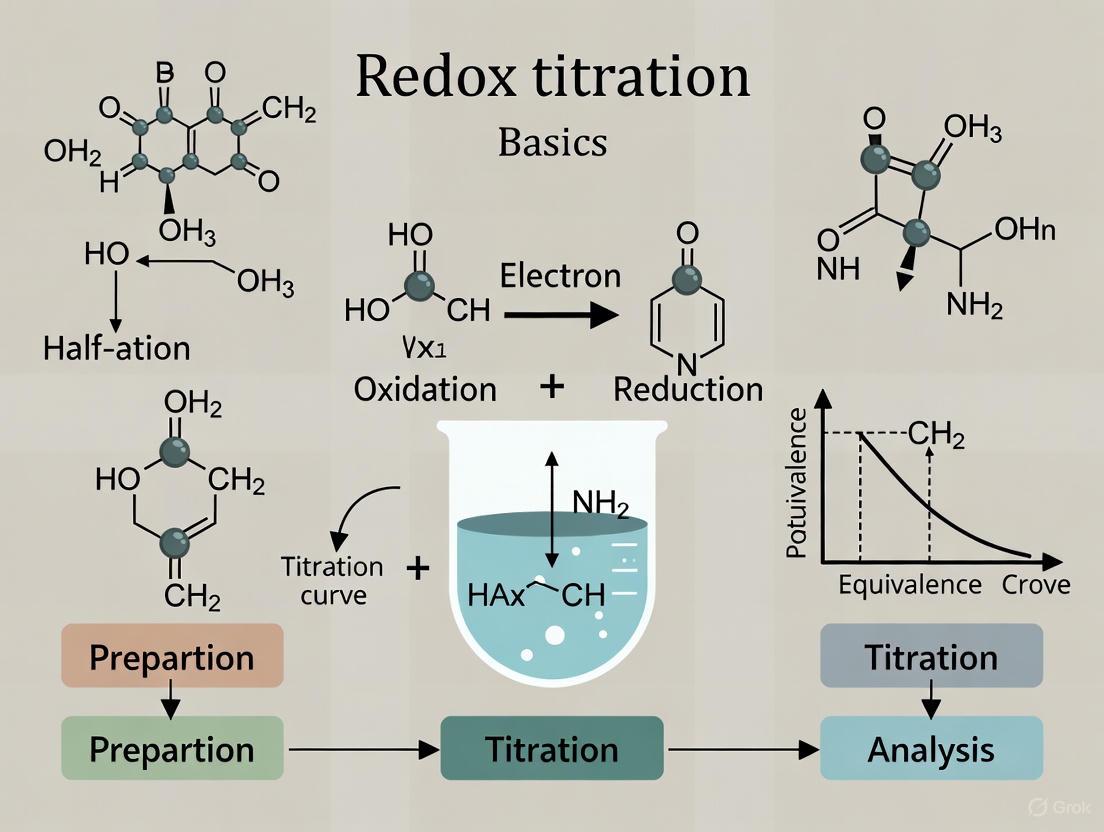

This article provides a comprehensive overview of redox titration, a foundational analytical technique based on electron-transfer reactions.

Redox Titration in Analytical Chemistry: Principles, Methods, and Advanced Applications for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of redox titration, a foundational analytical technique based on electron-transfer reactions. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores core principles from historical context to modern automated methodologies. The content details specific techniques like permanganometry and iodometry, highlights critical troubleshooting strategies for common errors, and examines advanced validation methods and comparative analyses with modern instrumental techniques. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with current innovations, this guide serves as a vital resource for implementing precise and reliable redox titrimetry in pharmaceutical analysis and quality control.

Understanding Redox Titration: Core Principles and Electron Transfer

Definition and Historical Context of Redox Titrimetry

Redox titrimetry stands as a cornerstone of quantitative chemical analysis, providing researchers and scientists with a robust methodology for determining the concentration of oxidizing and reducing agents in solution. This analytical technique relies on fundamental oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions, characterized by the transfer of electrons between the analyte and a standardized titrant [1] [2]. The development of redox titrimetry in the late 18th century marked a significant advancement in analytical chemistry, enabling precise measurements that were previously unattainable. Within the broader context of a thesis on the fundamentals of analytical chemistry research, understanding the historical evolution and theoretical underpinnings of redox titrimetry is paramount. Its applications span critical fields, including pharmaceutical development, where it is used to quantify active ingredients, environmental monitoring of pollutants, and industrial quality control processes [2]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the definition, historical origins, and theoretical foundations that form the basis of modern redox titration methods, with content structured specifically for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Definition and Core Principles

Redox titration is defined as a volumetric analytical technique that determines the concentration of a given analyte by instigating a stoichiometric oxidation-reduction reaction between the titrant and the analyte [1] [3]. The fundamental principle relies on the incremental addition of a solution of known concentration—the titrant, which serves as either an oxidizing or reducing agent—to the analyte solution until the equivalence point is reached. This point signifies that the moles of electrons lost by the reducing agent equal the moles of electrons gained by the oxidizing agent [2].

The reaction mechanism is governed by electron transfer, which manifests in changes in the oxidation states of the reactants. Oxidation involves the loss of electrons, an increase in oxidation state, and can involve the addition of oxygen or removal of hydrogen. Conversely, reduction involves the gain of electrons, a decrease in oxidation state, and can involve the addition of hydrogen or removal of oxygen [3]. The substance that accepts electrons is the oxidizing agent, and it is itself reduced. The substance that donates electrons is the reducing agent, and it is itself oxidized. The titration's progress is monitored by tracking the solution's potential, which is directly related to the concentrations of the oxidized and reduced species via the Nernst equation, forming the basis for the characteristic sigmoidal titration curve [4] [2].

Table 1: Fundamental Processes in Redox Reactions

| Process | Key Characteristics | Change in Electrons | Change in Oxidation State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation | Loss of electrons; addition of oxygen; removal of hydrogen. | Loss | Increase |

| Reduction | Gain of electrons; addition of hydrogen; removal of oxygen. | Gain | Decrease |

Unlike acid-base titrimetry, which relies on proton transfer, redox titrimetry hinges entirely on electron transfer processes. This makes it uniquely suited for analyzing a wide range of species that are redox-active, from metal ions like Fe²⁺ to organic molecules and halogens [2]. The endpoint, where the reaction is visually detected, is typically identified using self-indicating titrants or specific redox indicators that change color when the potential of the solution shifts sharply near the equivalence point [1] [5].

Historical Development

The genesis of redox titrimetry is intricately linked to the nascent field of volumetric analysis in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The first documented redox titration was introduced in 1787 by Claude Berthollet, who developed a quantitative method for analyzing chlorine water (a mixture of Cl₂, HCl, and HOCl) based on its ability to oxidize indigo [4] [5]. In this pioneering work, the decolorization of the blue indigo dye served as the indicator for the endpoint; the solution remained colorless until all the chlorine was consumed, after which excess indigo imparted a permanent color [4].

This methodology was expanded upon in 1814 by Joseph Gay-Lussac, who devised a similar titration for determining the available chlorine content in bleaching powder [4] [5]. These early methods established the foundational principles of using a standardized solution to titrate an analyte until a visual endpoint signaled the completion of the redox reaction.

The scope of redox titrimetry significantly broadened in the mid-1800s with the introduction of several new oxidizing and reducing titrants. Key among these were permanganate (MnO₄⁻), dichromate (Cr₂O₇²⁻), and iodine (I₂) as oxidizing agents, and iron(II) (Fe²⁺) and thiosulfate (S₂O₃²⁻) as reducing agents [4] [5]. Despite the availability of these new reagents, the widespread adoption of redox titrimetry was initially hampered by the lack of suitable indicators. A major breakthrough came in the 1920s with the introduction of diphenylamine, the first dedicated redox indicator [4] [5]. This was quickly followed by other indicators, such as ferroin, which undergo distinct, reversible color changes at specific solution potentials, thereby greatly enhancing the technique's accuracy and applicability [4] [2].

Table 2: Historical Milestones in Redox Titrimetry

| Year | Scientist | Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1787 | Claude Berthollet | First redox titration using chlorine to oxidize indigo. | Introduced the concept of quantitative analysis via redox reactions. |

| 1814 | Joseph Gay-Lussac | Titration method for chlorine in bleaching powder. | Applied redox titrimetry to industrial quality control. |

| Mid-1800s | Various Chemists | Introduction of MnO₄⁻, Cr₂O₇²⁻, I₂, Fe²⁺, and S₂O₃²⁻ as titrants. | Expanded the range of analyzable substances. |

| 1920s | -- | Introduction of diphenylamine and other redox indicators. | Solved the endpoint detection problem, making the technique more reliable and versatile. |

Theoretical Foundations

Electrode Potentials and the Nernst Equation

The thermodynamic driving force for any redox titration is the electrode potential (E), which quantifies the tendency of a species to gain electrons and be reduced [2]. The standard reduction potential (E°), measured under standard conditions (25°C, 1 M concentration, 1 atm pressure) relative to the Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE), provides a benchmark for comparing different redox couples [2]. A species with a more positive E° has a greater tendency to be reduced and will act as an oxidizing agent toward a species with a less positive E°.

In real titration conditions, concentrations deviate from the standard state. The Nernst Equation is used to calculate the potential under non-standard conditions. For a half-reaction of the form: [ \text{Oxidized form} + n e^- \rightleftharpoons \text{Reduced form} ] the Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E = E^\circ - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{[\text{Reduced}]}{[\text{Oxidized}]} ] where E is the electrode potential, E° is the standard reduction potential, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature in Kelvin, n is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction, F is the Faraday constant, and the logarithmic term is the reaction quotient Q [2]. At 25°C (298 K), this simplifies to: [ E = E^\circ - \frac{0.059}{n} \log \frac{[\text{Reduced}]}{[\text{Oxidized}]} ] This equation is pivotal for modeling the titration curve, as it mathematically describes how the solution potential changes with the ratio of reduced to oxidized species for a given half-reaction [4] [2].

Redox Titration Curves

A redox titration curve is a sigmoidal plot of the solution's potential (E) versus the volume of titrant added [4] [2]. The curve features a distinct sharp rise or fall at the equivalence point due to rapid changes in the concentrations of the redox species.

The potential at any point in the titration is calculated using the Nernst equation for the most convenient half-reaction. Before the equivalence point, the solution contains significant amounts of both the oxidized and reduced forms of the analyte, and the potential is calculated using the analyte's half-reaction and its respective E° value [4] [5]. After the equivalence point, an excess of titrant exists, and the potential is more easily calculated using the Nernst equation for the titrant's half-reaction [4] [5]. The magnitude of the potential jump at the equivalence point is largest when the difference between the standard potentials of the titrant and analyte half-reactions is large [2].

Experimental Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of redox titrations requires a set of specialized reagents and materials. The selection of titrants and indicators is critical and depends on the specific analyte and the required reaction potential.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Titration

| Reagent Name | Chemical Formula | Function & Role | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate | KMnO₄ | oxidizing titrant; self-indicating (purple to colorless). | Titration of Fe²⁺, oxalic acid, and other reducing agents in acidic medium. |

| Potassium Dichromate | K₂Cr₂O₇ | oxidizing titrant; requires separate indicator. | Determination of Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) in wastewater; iron ore analysis. |

| Iodine Solution | I₂ | mild oxidizing titrant. | Iodimetric titrations of direct reducing agents like arsenite. |

| Sodium Thiosulfate | Na₂S₂O₃ | reducing titrant. | Iodometric titrations for analysis of oxidizing agents (e.g., chlorine, hypochlorite). |

| Ceric Sulfate | Ce(SO₄)₂ | strong oxidizing titrant. | Pharmaceutical analysis; stable in acidic solutions. |

| Ferroin Indicator | [Fe(phen)₃]²⁺ | redox indicator (red to pale blue at ~1.06 V). | Used with dichromate and ceric sulfate titrations. |

| Diphenylamine | (C₆H₅)₂NH | redox indicator (colorless to violet). | Historically important for iron and dichromate titrations. |

| Starch Solution | (C₆H₁₀O₅)ₙ | specific indicator for iodine (forms blue complex). | Used as endpoint indicator in iodometric and iodimetric titrations. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Titration of KMnO₄ against Oxalic Acid

The titration of potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) with oxalic acid (H₂C₂O₄) is a classic redox experiment that demonstrates key principles and techniques [3].

Principle: Oxalic acid acts as the reducing agent, while permanganate acts as the oxidizing agent. The reaction is carried out in an acidic medium (dilute H₂SO₄), which enhances the oxidizing power of permanganate and prevents the formation of manganese dioxide (MnO₂) [3]. KMnO₄ is self-indicating; its intense purple color disappears as it is reduced to nearly colorless Mn²⁺ ions until the equivalence point, where the first persistent pale pink color appears.

Reactions:

- Ionic Half-Reactions:

- Overall Ionic Equation:

- ( 2MnO4^- + 5C2O4^{2-} + 16H^+ \rightarrow 2Mn^{2+} + 10CO2 + 8H_2O ) [3]

Materials and Reagents:

- Standard 0.1 M oxalic acid solution (Primary Standard)

- Potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) solution of unknown concentration

- Dilute sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), approximately 1 M

- Burette, pipette, conical flask, burette stand, white tile

- Heating apparatus (for initial warming of the oxalic acid solution)

Procedure:

- Preparation of Standard Oxalic Acid Solution: Accurately weigh about 3.15 g of pure oxalic acid dihydrate (H₂C₂O₄·2H₂O; Molar Mass = 126 g/mol). Transfer it quantitatively to a 250 mL volumetric flask, dissolve in distilled water, and make up to the mark to obtain a 0.1 M solution [3].

- Titration: a. Pipette 20 mL of the standard oxalic acid solution into a clean conical flask. b. Add about 20 mL of dilute H₂SO₄ to the flask to provide the acidic medium. c. Warm the solution to about 60-70°C to facilitate the reaction rate. Note: Do not overheat. d. Fill the burette with the KMnO₄ solution and note the initial reading. e. Titrate the warm oxalic acid solution with KMnO₄ from the burette, constantly swirling the flask, until the first permanent pale pink color persists for at least 30 seconds. This is the endpoint. f. Repeat the titration several times to obtain concordant values.

- Calculation: From the balanced equation, 2 moles of KMnO₄ react with 5 moles of oxalic acid. [ \text{Moles of Oxalic acid used} = M{acid} \times V{acid} ] [ \text{Moles of KMnO₄ reacted} = \frac{2}{5} \times \text{Moles of Oxalic acid} ] [ \text{Molarity of KMnO₄} (M{KMnO4}) = \frac{\text{Moles of KMnO₄ reacted}}{V{KMnO4} \text{ (in L)}} ]

Redox titrimetry has evolved from its origins in 18th-century chlorine analysis into a sophisticated and indispensable analytical methodology. Its foundation is built upon a clear definition—the quantitative determination of an analyte via a stoichiometric electron-transfer reaction—and a rich historical context marked by key innovations in titrants and indicators. The robust theoretical framework, governed by electrode potentials and the Nernst equation, allows researchers to predict and interpret the sigmoidal titration curves characteristic of these reactions. For the modern researcher, particularly in demanding fields like drug development, mastering the core principles, standard reagents, and detailed protocols of redox titrimetry—as exemplified by the classic permanganate-oxalic acid titration—is fundamental. This technique provides a reliable, precise, and versatile tool for quantitative analysis, cementing its enduring value in the analytical chemist's toolkit.

In the quantitative landscape of analytical chemistry research, redox titrations stand as a pillar for determining the concentration of unknown substances by measuring the electron transfer in a reduction-oxidation (redox) reaction [6]. At the heart of every redox process lies the fundamental principle of oxidation and reduction half-reactions—a conceptual framework that allows scientists to deconstruct complex electron-transfer processes into manageable, balanceable components. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of this principle is not merely academic; it is essential for designing robust analytical methods, characterizing active pharmaceutical ingredients with redox properties, and understanding the biochemical pathways critical to drug mechanisms [7]. This whitepaper delineates the theoretical underpinnings of half-reactions, provides detailed experimental methodologies for their study, and contextualizes their indispensable role within modern analytical research.

Theoretical Foundations of Half-Reactions

Defining Oxidation, Reduction, and Half-Reactions

A redox reaction is a chemical process involving the complete transfer of electrons between two species [8]. This electron exchange manifests as complementary processes:

- Oxidation is the loss of electrons by a molecule, atom, or ion [9].

- Reduction is the gain of electrons by a molecule, atom, or ion [9].

A half-reaction is the part of a redox reaction that explicitly shows either the oxidation process (electron loss) or the reduction process (electron gain). Since electrons can neither be created nor destroyed in a chemical reaction, every oxidation half-reaction must be paired with a reduction half-reaction, and the number of electrons lost in the oxidation must equal the number gained in the reduction [9].

The species that causes oxidation by accepting electrons is termed the oxidizing agent (or oxidant), and it is itself reduced. Conversely, the species that causes reduction by donating electrons is the reducing agent (or reductant), and it is itself oxidized [8] [9]. This relationship is fundamental to understanding electron flow.

The Role of Oxidation Numbers

The oxidation number (or oxidation state) is a conceptual charge assigned to an atom in a substance, as if the compound was ionic [9]. Tracking changes in oxidation numbers provides a definitive method for identifying redox reactions and distinguishing the half-reactions.

Table 1: Standard Rules for Assigning Oxidation Numbers

| Rule # | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | The oxidation number of an atom in an elemental substance is 0. |

| 2 | The oxidation number of a monatomic ion is equal to the ion's charge. |

| 3 | Hydrogen is generally +1, and oxygen is generally -2 in compounds. |

| 4 | The sum of oxidation numbers in a neutral compound is zero; in a polyatomic ion, it equals the ion's charge. |

Based on these rules, one can define oxidation as an increase in oxidation number and reduction as a decrease in oxidation number [9].

Conceptual Workflow for Redox Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of analyzing a redox reaction by decomposing it into its constituent half-reactions, a core skill for any researcher working with electron-transfer processes.

Experimental Application in Redox Titration

Principles of Redox Titration

Redox titration is an analytical technique that leverages a redox reaction to determine the concentration of an unknown analyte [7]. It involves the gradual addition of a titrant—a standard solution of known concentration of an oxidizing or reducing agent—to the analyte until the reaction is complete, a point known as the equivalence point [6]. The power of this technique in research and industrial quality control lies in its precision and applicability to a wide range of redox-active substances, from metal ions like iron to organic molecules like vitamin C [7].

The course of a redox titration is monitored by a titration curve, a plot of the solution's potential (E) versus the volume of titrant added. This curve is S-shaped, characterized by a steady rise in potential followed by a sudden jump near the equivalence point [4] [6]. The potential of the solution is governed by the Nernst equation, which relates the potential to the concentrations of the oxidized and reduced forms of the species involved [4]. Before the equivalence point, the potential is easiest to calculate using the Nernst equation for the analyte's half-reaction; after the equivalence point, the potential is best calculated using the Nernst equation for the titrant's half-reaction [4] [5].

Key Reagents and Indicators in Redox Titration

A successful redox titration requires careful selection of titrants and indicators. The choice often depends on the specific analyte and the required reaction conditions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Titration

| Reagent / Indicator | Function & Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | A strong oxidizing titrant used in permanganometry. It can serve as a self-indicator, changing from purple (MnO₄⁻) to nearly colorless (Mn²⁺) at the endpoint [7]. |

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | A strong oxidizing titrant used in dichromatometry, often for determining iron content. It is a primary standard [7]. |

| Iodine (I₂) | An oxidizing titrant used in iodometry, typically for analyzing reducing agents like thiosulfate [7]. |

| Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) | A common reducing titrant used in iodometric titrations [7]. |

| Starch Indicator | A visual indicator that forms an intense dark blue complex with iodine, used to detect the endpoint in iodometric titrations [7] [6]. |

| Redox Indicators (e.g., Diphenylamine) | Highly colored dyes that exhibit distinct colors in their oxidized and reduced states. They are selected based on their formal potential to signal the endpoint [4] [6]. |

| Pre-treatment Reagents (e.g., SnCl₂, Zn) | Auxiliary oxidizing or reducing agents used to pre-treat the analyte, ensuring it is in a single, well-defined oxidation state before titration begins [6]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Determination of Iron Content

The quantification of iron via redox titration with potassium permanganate is a classic and highly relevant analytical procedure in pharmaceutical and material sciences.

Objective: To determine the concentration of iron (as Fe²⁺) in an unknown sample via titration with a standardized potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) solution.

Principle: In an acidic medium, MnO₄⁻ ions oxidize Fe²⁺ ions to Fe³⁺. The purple color of KMnO₄ serves as a self-indicator, providing a permanent pink endpoint when the first trace of excess titrant is present. The underlying half-reactions and full balanced equation are [7]:

- Oxidation Half-Reaction: ( \ce{Fe^{2+} -> Fe^{3+} + e^{-}} ) (multiplied by 5)

- Reduction Half-Reaction: ( \ce{MnO4^{-} + 8H+ + 5e^{-} -> Mn^{2+} + 4H2O} )

- Full Balanced Equation: ( \ce{5Fe^{2+} + MnO4^{-} + 8H+ -> 5Fe^{3+} + Mn^{2+} + 4H2O} )

Materials and Equipment:

- Burette (50 mL)

- Analytical balance

- Volumetric flask (250 mL)

- Conical flasks (250 mL)

- Pipette (25 mL)

- Graduated cylinder

- Standard KMnO₄ solution (~0.02 M)

- Unknown iron (Fe²⁺) sample solution

- Dilute sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄, ~1 M)

- Safety Equipment: Lab coat, safety glasses, gloves

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh a known mass of the unknown iron sample and dissolve it in dilute sulfuric acid (not HCl, as Cl⁻ can be oxidized) in a 250 mL volumetric flask. Dilute to the mark with deionized water. The acid environment prevents the hydrolysis of Fe³⁺ and provides the H⁺ ions required by the reduction half-reaction.

- Titration Setup: Rinse and fill a clean burette with the standardized KMnO₄ solution. Record the initial burette reading.

- Aliquot Transfer: Pipette a 25.00 mL aliquot of the prepared iron sample solution into a clean 250 mL conical flask. Add approximately 20 mL of additional dilute H₂SO₄ to ensure sufficient acidity.

- Titration Execution: Titrate the iron solution with KMnO₄ from the burette while continuously swirling the flask. The initial purple color will decolorize rapidly as it reacts with Fe²⁺.

- Endpoint Determination: Continue the titration until a faint pink color persists for at least 30 seconds. This indicates that all Fe²⁺ has been oxidized and a slight excess of KMnO₄ is present. Record the final burette reading.

- Replication: Repeat the titration at least in triplicate to obtain consistent results.

Calculations and Data Analysis:

- Calculate the volume of KMnO₄ used in each titration.

- From the molarity of the KMnO₄ standard solution and the volume used, calculate the moles of KMnO₄ consumed.

- Using the stoichiometry of the balanced equation (5 mol Fe²⁺ : 1 mol MnO₄⁻), calculate the moles of Fe²⁺ in the titrated aliquot.

- Calculate the concentration of Fe²⁺ in the original sample solution.

- Determine the average concentration and the standard deviation across replicates.

Table 3: Exemplar Data Table for Iron Determination Titration

| Trial | Mass of Sample (g) | KMnO₄ Volume Used (mL) | Moles of KMnO₄ (mol) | Moles of Fe²⁺ (mol) | Fe²⁺ Concentration (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.254 | 24.55 | ( 4.91 \times 10^{-4} ) | ( 2.455 \times 10^{-3} ) | 0.0982 |

| 2 | 1.254 | 24.52 | ( 4.90 \times 10^{-4} ) | ( 2.452 \times 10^{-3} ) | 0.0981 |

| 3 | 1.254 | 24.60 | ( 4.92 \times 10^{-4} ) | ( 2.460 \times 10^{-3} ) | 0.0984 |

| Average: | 0.0982 ± 0.0002 |

Advanced Considerations for Research Applications

The Nernst Equation and Formal Potential

For the research scientist, a deep understanding of the Nernst equation is critical for interpreting titration curves and predicting reaction feasibility beyond standard conditions. The Nernst equation for a generic half-reaction is expressed as: [ E = E^{\circ} - \frac{RT}{nF}\ln Q ] where ( E ) is the electrode potential, ( E^{\circ} ) is the standard electrode potential, ( R ) is the gas constant, ( T ) is the temperature in Kelvin, ( n ) is the number of electrons transferred, ( F ) is the Faraday constant, and ( Q ) is the reaction quotient [4]. In practice, the formal potential is often used instead of the standard potential. The formal potential is a matrix-adjusted value that accounts for the specific experimental conditions (e.g., acid concentration, ionic strength), making it more accurate for real-world analytical calculations [4] [5].

Workflow for a Potentiometric Redox Titration

Advanced research often employs potentiometric methods for endpoint detection, which is particularly useful for colored solutions or when a suitable visual indicator is unavailable. The following workflow details this automated and highly precise technique.

The decomposition of redox reactions into their constituent oxidation and reduction half-reactions is more than a theoretical exercise—it is a fundamental practice that empowers precise analytical measurement. This principle enables researchers to balance complex electron-transfer equations, understand the thermodynamics governing redox processes via the Nernst equation, and design accurate quantitative methods like redox titration [8] [9]. From the quality control of pharmaceuticals like ascorbic acid to the analysis of iron in supplements and the assessment of environmental water quality, the applications of this foundational knowledge are vast and critical [7]. As analytical techniques continue to evolve, the clear understanding of electron flow through half-reactions remains an indispensable tool for scientists driving innovation in research and drug development.

Redox titrimetry stands as a cornerstone technique in analytical chemistry, enabling the precise quantification of substances that undergo electron transfer reactions. This whitepaper delineates the core components of redox titration—oxidizing agents, reducing agents, and the critical concept of the equivalence point—framed within contemporary analytical research. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide integrates fundamental principles with advanced methodological considerations, supported by structured data and visualization tools to facilitate application in rigorous laboratory settings.

Redox titration is an analytical method used to determine the concentration of an unknown analyte by measuring its reaction with a standardized titrant, where the underlying chemical reaction involves the transfer of electrons between the reactants [10]. The technique, first developed in the late 18th century for analyzing chlorine water, has evolved significantly with the introduction of robust titrants and indicators, expanding its applicability across pharmaceutical, environmental, and industrial analytics [5] [4]. The fundamental process involves a reducing agent (the species that donates electrons and is oxidized) and an oxidizing agent (the species that accepts electrons and is reduced) [11]. The point of completion, known as the equivalence point, is reached when the amount of titrant added is stoichiometrically equivalent to the amount of analyte present, a condition that can be monitored through potential changes or indicator color shifts [12].

Core Theoretical Components

Oxidizing and Reducing Agents

In redox titrations, the active chemical species are classified based on their electron transfer behavior, and their effectiveness is governed by standard reduction potentials and reaction kinetics.

- Oxidizing Agents: These species accept electrons from the analyte, thereby undergoing reduction themselves. Strong oxidizing agents possess a high affinity for electrons, a property quantified by their highly positive standard reduction potentials [11].

- Reducing Agents: These species donate electrons to the analyte, thereby undergoing oxidation themselves. Effective reducing agents readily give up electrons, indicated by their low (often negative) standard reduction potentials [11].

The table below summarizes common agents used in redox titrations and their typical applications in analytical chemistry.

Table 1: Common Oxidizing and Reducing Agents in Redox Titration

| Agent Type | Common Reagents | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Oxidizing Agents | Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄), Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇), Ceric Sulfate (Ce(SO₄)₂), Iodine (I₂) | Determination of Fe²⁺, oxalic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and other reducing analytes [7] [13] [14]. |

| Reducing Agents | Iron (II) salts (Fe²⁺), Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃), Oxalic Acid (H₂C₂O₄) | Determination of oxidizing agents like I₂, KMnO₄, and K₂Cr₂O₇ [5] [13]. |

The Equivalence Point

The equivalence point is the theoretical point in a titration where the amount of titrant added is exactly stoichiometrically equivalent to the amount of analyte present in the solution [12]. In the context of a redox reaction, this is the point at which the number of moles of electrons lost by the reducing agent equals the number of moles of electrons gained by the oxidizing agent [13].

Accurately determining this point is paramount for correct calculations. The relationship between the reaction's progress and the electrochemical potential of the solution is described by the Nernst equation [5] [4]. This equation allows researchers to model the titration curve and understand how potential changes with titrant volume.

- Before the Equivalence Point: The potential of the system is best calculated using the Nernst equation for the analyte's half-reaction, as its concentration ratio is known [5] [4].

- After the Equivalence Point: The potential is more conveniently calculated using the Nernst equation for the titrant's half-reaction, which is now in excess [5] [4].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying the equivalence point in a redox titration.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section provides a detailed, application-oriented protocol for a classic redox titration, representative of methods used in quantitative analysis.

Detailed Protocol: Determination of Iron Content by Permanganate Titration

This method is widely used for determining the iron content in ores, alloys, and pharmaceutical compounds [7] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) Std. Solution | The oxidizing titrant. It undergoes reduction from MnO₄⁻ (purple) to Mn²⁺ (colorless) [7] [14]. |

| Iron (II) Sample Solution (Analyte) | The unknown reducing agent to be quantified. It is oxidized from Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺ [14]. |

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄), 1 M | Provides an acidic medium essential for the reaction, preventing the precipitation of manganese dioxide [7] [12]. |

| Burette | Precision glassware for dispensing the KMnO₄ titrant [10]. |

| Conical Flask | Reaction vessel for the titration. |

| Potassium Permanganate as Self-Indicator | The intense purple color of MnO₄⁻ signals the endpoint with the first persistent pink color [7]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Accurately measure a known volume (e.g., 25.00 mL) of the iron (II) sample solution and transfer it to a clean conical flask [14].

- Acidification: Add approximately 10 mL of 1 M sulfuric acid to the flask to create a strongly acidic environment [7] [12].

- Titration Setup: Fill a clean burette with the standardized potassium permanganate solution. Record the initial burette reading.

- Titration and Endpoint Detection: Slowly add the KMnO₄ solution to the acidified iron (II) solution while continuously swirling the flask. Initially, the purple color of the permanganate will decolorize upon contact. Continue the addition until the first faint, permanent pink color persists for at least 30 seconds. This color change marks the endpoint of the titration [7] [14]. Record the final burette reading.

- Calculation: The balanced chemical equation for the reaction is: [5\text{Fe}^{2+} + \text{MnO}4^- + 8\text{H}^+ \rightarrow 5\text{Fe}^{3+} + \text{Mn}^{2+} + 4\text{H}2\text{O}] Using the stoichiometry (5 mol Fe²⁺ : 1 mol MnO₄⁻), the concentration of the iron (II) solution can be calculated as follows [14]: a. Moles of KMnO₄ used = Molarity of KMnO₄ × Volume (L) of KMnO₄ used. b. Moles of Fe²⁺ = Moles of KMnO₄ used × 5. c. Concentration of Fe²⁺ = Moles of Fe²⁺ / Volume (L) of the analyte solution.

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Advanced Considerations and Titration Types

Classification of Redox Titrations

Redox titrations are categorized based on the specific titrant and reaction mechanism employed. The choice of method depends on the analyte and the required precision.

Table 3: Common Types of Redox Titrations

| Titration Type | Key Titrant | Analyte Examples | Endpoint Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permanganometry | Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | Fe²⁺, Oxalic Acid, H₂O₂ | Self-indicator (colorless to pink) [7] [13]. |

| Dichromatometry | Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Fe²⁺ | Redox indicator (e.g., diphenylamine; orange to green) [13] [14]. |

| Iodometry | Iodine (I₂) | Reducing agents (e.g., Thiosulfate) | Starch indicator (blue to colorless) [7] [13]. |

| Cerimetry | Ceric Sulfate (Ce(SO₄)₂) | Fe²⁺, Pharmaceuticals | Redox indicator (e.g., Ferroin; yellow to colorless) [13]. |

Indicator Selection and Endpoint Detection

Detecting the endpoint with high accuracy is critical. While some titrants like KMnO₄ are self-indicating, others require specific redox indicators.

- Redox Indicators: These are organic compounds that exhibit different colors in their oxidized and reduced states. The indicator changes color within a specific range of solution potential, which should coincide with the steep potential jump at the equivalence point of the titration [14]. Common examples include diphenylamine (for dichromate titrations) and ferroin (for cerimetry) [5] [14].

- Instrumental Methods: For titrations without a sharp visual color change or for highly colored solutions, instrumental methods are preferred.

- Potentiometry: An oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) probe measures the voltage of the solution relative to a reference electrode, allowing for the construction of a precise titration curve. The equivalence point is identified as the point of maximum slope (inflection) on the curve [11] [13].

- Other Techniques: Amperometric and conductometric titrations offer alternative detection methods for specialized applications [13].

A comprehensive understanding of the key components—oxidizing agents, reducing agents, and the equivalence point—is fundamental to executing accurate and reliable redox titrations. The selection of an appropriate titrant and a robust method for endpoint detection, whether visual or instrumental, directly impacts the quality of analytical results. As a versatile and precise tool, redox titrimetry continues to be indispensable in research and quality control laboratories, from quantifying active pharmaceutical ingredients to monitoring environmental pollutants. Mastery of its core principles, as outlined in this guide, provides a solid foundation for its effective application in solving complex analytical challenges.

Redox titrations are a fundamental technique in analytical chemistry, used for the quantitative determination of oxidizing or reducing agents. These methods are based on oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions between the analyte and a standard titrant, involving the transfer of electrons [15]. The development of redox titrimetry dates back to the late 18th century when Claude Berthollet introduced a method for analyzing chlorine water based on its ability to oxidize indigo [16]. The field expanded significantly in the mid-1800s with the introduction of common titrants like MnO₄⁻, Cr₂O₇²⁻, and I₂ as oxidizing agents, and Fe²⁺ and S₂O₃²⁻ as reducing agents [16].

Within the broader context of analytical chemistry research, understanding the theoretical principles behind redox titration curves is essential for method development, optimization, and accurate endpoint determination. This technical guide explores the core relationship between redox titration curves and the Nernst equation, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge required to implement these techniques in complex analytical scenarios, including the study of metalloenzymes and pharmaceutical compounds.

Theoretical Foundations

The Nernst Equation

The Nernst equation is a fundamental thermodynamic relationship that enables the calculation of the reduction potential of an electrochemical reaction under non-standard conditions. Formulated by Walther Nernst, this equation relates the measured cell potential to the standard electrode potential, temperature, number of electrons transferred, and activities (often approximated by concentrations) of the chemical species involved [17].

For a general half-reaction: [ \text{Ox} + z\text{e}^- \longrightarrow \text{Red} ]

The Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}} ] where:

- ( E_{\text{red}} ) is the half-cell reduction potential at the temperature of interest,

- ( E_{\text{red}}^{\ominus} ) is the standard half-cell reduction potential,

- ( R ) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹),

- ( T ) is the temperature in kelvins,

- ( z ) is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction,

- ( F ) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹),

- ( a{\text{Red}} ) and ( a{\text{Ox}} ) are the activities of the reduced and oxidized forms, respectively [17].

At room temperature (25°C), this equation simplifies to: [ E = E^{\ominus} - \frac{0.05916\, \text{V}}{z} \log_{10} \frac{[\text{Red}]}{[\text{Ox}]} ] This simplified form is particularly useful for laboratory applications [18] [15].

Formal Potential: A Practical Adaptation

In practical applications where activity coefficients are unknown or difficult to determine, the formal potential (( E^{\ominus'} )) is often used. The formal potential is the experimentally measured potential under specified conditions where the concentration ratio of redox species is unity, accounting for medium effects and activity coefficients [17]: [ E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus'} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{C{\text{Red}}}{C{\text{Ox}}} ] where ( E_{\text{red}}^{\ominus'} ) incorporates the activity coefficients and provides a more practical value for quantitative calculations in real solutions [17].

Redox Titration Curves

Fundamental Principles

A redox titration curve graphically represents the change in electrochemical potential as a function of titrant volume added. The curve typically exhibits a sigmoidal shape with a steep potential jump near the equivalence point [15]. The potential change occurs because the concentrations of the oxidized and reduced forms of the analyte change throughout the titration, affecting the system's potential according to the Nernst equation [16].

Consider a titration where a reduced form of the titrand (A₍red₎) reacts with an oxidized form of the titrant (B₍ox₎): [ \text{A}\text{red} + \text{B}\text{ox} \rightleftharpoons \text{B}\text{red} + \text{A}\text{ox} ]

The reaction potential is the difference between the reduction potentials of the two half-reactions [16]: [ E\text{rxn} = E{\text{B}\text{ox}/\text{B}\text{red}} - E{\text{A}\text{ox}/\text{A}_\text{red}} ]

Calculating Titration Curves

The calculation of a redox titration curve involves applying the Nernst equation to different regions of the titration, with the specific approach depending on the proximity to the equivalence point [16]:

Before the equivalence point: The potential is dominated by the titrand's redox couple, as the titrant concentration is very small. The potential is calculated using the Nernst equation for the titrand's half-reaction: [ E\textrm{rxn} = E^o{A\mathrm{ox}/A\mathrm{red}} - \dfrac{RT}{nF} \ln \dfrac{[A\textrm{red}]}{[A\textrm{ox}]} ]

After the equivalence point: The potential is dominated by the titrant's redox couple, with the calculation based on the titrant's half-reaction: [ E\textrm{rxn} = E^o{B\mathrm{ox}/B\mathrm{red}} - \dfrac{RT}{nF} \ln \dfrac{[B\textrm{red}]}{[B\textrm{ox}]} ]

At the equivalence point: Stoichiometric amounts of titrand and titrant have reacted, and the potential can be calculated by combining both Nernst equations, recognizing that the potentials of both half-reactions are equal at equilibrium [16].

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for calculating and interpreting a redox titration curve:

Factors Affecting Titration Curve Characteristics

Several factors influence the shape and characteristics of redox titration curves:

- Standard potential difference: A larger difference between the standard potentials of the titrant and titrand results in a more pronounced potential jump at the equivalence point [15].

- Number of electrons transferred: Reactions involving more electrons (higher ( z )) produce steeper titration curves [15].

- Solution conditions: pH, complexing agents, and ionic strength can affect formal potentials and thus alter the titration curve [19] [15].

- Concentrations: Higher concentrations typically lead to larger potential changes at the equivalence point [15].

Experimental Methodologies

Potentiometric Monitoring

Potentiometry provides a precise and objective method for monitoring redox titrations by measuring the potential of an electrochemical cell under zero-current conditions [15]. The experimental setup consists of:

- Indicator electrode: Typically an inert metallic electrode (platinum or gold) that provides a surface for electron transfer without participating in the reaction [15].

- Reference electrode: Maintains a constant, known potential (e.g., saturated calomel electrode or Ag/AgCl electrode) [15].

- Salt bridge: Completes the electrical circuit while preventing mixing of solutions [15].

The cell potential is measured as: [ E{\text{cell}} = E{\text{indicator}} - E{\text{reference}} + E{\text{liquid junction}} ] where the liquid junction potential is minimized through proper salt bridge design [15].

Endpoint Detection Methods

Several analytical approaches can determine the equivalence point in redox titrations:

- Visual indicators: Substances that change color at a specific electrode potential (e.g., ferroin, diphenylamine sulfonate) [15]. Some titrants like potassium permanganate are self-indicating [20].

- Potentiometric endpoint detection: The equivalence point is identified as the point of maximum slope on the titration curve, which can be determined precisely using first or second derivative plots [15].

- Starch indicator: Used specifically in iodometric titrations, forming a deep blue complex with iodine that disappears at the endpoint [20].

The following experimental workflow outlines the key steps in performing a potentiometric redox titration:

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Redox Titrations

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | Strong oxidizing titrant [15] [20] | Self-indicating (purple to colorless), requires acidic conditions [20] |

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Oxidizing titrant [15] | Primary standard, orange to green color change [15] |

| Cerium(IV) Sulfate (Ce(SO₄)₂) | Oxidizing titrant [15] | Powerful oxidant, yellow to colorless [15] |

| Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) | Reducing titrant for iodine [15] [20] | Used in iodometry, requires starch indicator [20] |

| Iodine (I₂) | Oxidizing titrant [15] | Moderate strength, used with starch indicator (blue complex) [20] |

| Iron(II) Salts (e.g., FeSO₄) | Reducing titrant [15] | Susceptible to aerial oxidation [15] |

| Platinum Electrode | Indicator electrode for potentiometry [15] | Inert surface for electron transfer [15] |

| Reference Electrode (SCE/AgAgCl) | Stable potential reference [15] | Provides constant reference potential [15] |

| Redox Indicators (e.g., Ferroin) | Visual endpoint detection [15] | Changes color at specific potential [15] |

Quantitative Aspects and Data Analysis

Titration Curve Calculations

Table 2: Nernst Equation Applications in Different Titration Regions

| Titration Region | Governing Equation | Key Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Before Equivalence Point | ( E = E^o{A\mathrm{ox}/A\mathrm{red}} - \dfrac{0.05916}{n} \log \dfrac{[A\textrm{red}]}{[A_\textrm{ox}]} ) | Dominated by titrand ratio [16] |

| At Equivalence Point | ( E{eq} = \dfrac{n1E^o1 + n2E^o2}{n1 + n_2} ) | Combined potential where [Ox] = [Red] [16] |

| After Equivalence Point | ( E = E^o{B\mathrm{ox}/B\mathrm{red}} - \dfrac{0.05916}{n} \log \dfrac{[B\textrm{red}]}{[B_\textrm{ox}]} ) | Dominated by titrant ratio [16] |

Practical Calculation Example

In a typical redox titration calculation, such as determining iron content using potassium permanganate:

Write the balanced redox equation: [ \text{MnO}4^- + 5\text{Fe}^{2+} + 8\text{H}^+ \rightarrow \text{Mn}^{2+} + 5\text{Fe}^{3+} + 4\text{H}2\text{O} ] [20]

Calculate moles of titrant used: [ n{\text{MnO}4^-} = C{\text{MnO}4^-} \times V{\text{MnO}4^-} ] [20]

Apply stoichiometric ratios: [ n{\text{Fe}^{2+}} = 5 \times n{\text{MnO}_4^-} ] [20]

Determine analyte concentration: [ C{\text{Fe}^{2+}} = \frac{n{\text{Fe}^{2+}}}{V_{\text{solution}}} ] [20]

Advanced Applications in Research

Titration of Complex Metalloenzymes

Redox titrations have been successfully applied to complex metalloenzymes containing multiple redox centers. The methodology involves reacting quantified aliquots of a redox titrant with a known amount of enzyme while monitoring redox-dependent spectroscopic properties. The resulting data is plotted as spectral changes versus the number of redox equivalents added, allowing researchers to generate theoretical titration curves based on candidate descriptions of the redox system [21].

This approach has been implemented for:

- NiFe hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio gigas: Contains NiFe active site cluster, proximal [Fe₄S₄]²⁺/¹⁺ cluster, [Fe₃S₄]¹⁺/⁰ cluster, and distal [Fe₄S₄]²⁺/¹⁺ cluster [21].

- Acetyl-coenzyme A synthase from Clostridium thermoaceticum: Features complex redox behavior requiring precise potentiometric titration methods [21].

Addressing Research Challenges

The application of redox titrations to complex biochemical systems presents unique challenges:

- Uncertain metal content: Routine metal and protein concentration determinations often have combined relative uncertainties of 20% or more [21].

- Spectroscopic ambiguity: Spectral features may arise from well-behaved isolated redox centers, coupled redox centers, or spin-state mixtures [21].

- Multiple redox states: Enzymes may stabilize in various redox states, each with distinct spectroscopic signatures [21].

Despite these challenges, the method provides a solid foundation for building accurate catalytic mechanisms by determining the number of redox-active centers, their reduction potentials, and their relationships to spectroscopic features [21].

Redox titration curves and the Nernst equation provide a powerful framework for quantitative analysis in analytical chemistry and biochemical research. The theoretical foundation established by the Nernst equation enables researchers to predict and interpret titration behavior, while modern potentiometric methods allow for precise endpoint detection even in complex systems. The continued application of these principles to challenging research areas, such as metalloenzyme characterization, demonstrates the enduring value of mastering these fundamental concepts. As redox titrimetry evolves with advances in instrumentation and data analysis, the core relationship between titration curves and the Nernst equation remains central to extracting meaningful quantitative information from redox reactions.

Redox titration is a fundamental volumetric analytical method based on a reduction-oxidation (redox) reaction between the analyte and the titrant [1]. This technique is indispensable in analytical chemistry research for determining the concentration of an unknown substance by leveraging electron transfer processes [7]. The core principle involves the titrant, an oxidizing or reducing agent of known concentration, reacting with the analyte until the equivalence point is reached, which is often detected using a suitable indicator or a potentiometer [22] [23]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical overview of three principal redox titration methods—Permanganometry, Iodometry, and Dichromatometry—framed within the broader context of their applications in scientific and industrial research, particularly in drug development and quality control.

These methods are classified based on the specific titrant used, each with distinct reaction mechanisms, experimental requirements, and applications. Permanganometry employs potassium permanganate as a powerful oxidant, iodometry utilizes iodine-thiosulfate chemistry, and dichromatometry is based on potassium dichromate as an oxidizing agent [24] [23]. Understanding their theoretical foundations, optimal conditions, and procedural nuances is critical for researchers to apply these techniques accurately for quantitative chemical analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of Redox Titrations

Redox titrations are governed by the transfer of electrons between chemical species. The analyte undergoes either oxidation (loss of electrons) or reduction (gain of electrons), while the titrant undergoes the complementary process [7]. The point at which the quantity of titrant added is stoichiometrically equivalent to the amount of analyte is the equivalence point, which is typically signaled by a measurable endpoint [22].

The feasibility and completeness of a redox reaction used for titration are determined by the standard reduction potentials of the involved couples. A significant difference in the reduction potentials of the oxidizing and reducing agents indicates a spontaneous and complete reaction, which is essential for an accurate titration [25]. Furthermore, factors such as reaction rate, stoichiometry, and the influence of pH and temperature must be considered during method development to ensure reproducible and reliable results [23].

Permanganometry

Principle and Reaction Mechanisms

Permanganometry is a redox titration method that uses potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) as a powerful oxidizing agent [25] [24]. The key to its utility lies in the varying reduction pathways of the permanganate ion (MnO₄⁻) under different pH conditions, which directly influence its oxidation state and standard reduction potential [25].

The specific reaction pathway is critically dependent on the pH of the solution, as summarized in the table below:

Table 1: Reduction of Permanganate (MnO₄⁻) Under Different pH Conditions

| Medium | Reduction Reaction | Product | Color Change | Standard Reduction Potential (E°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Acidic | MnO₄⁻ + 8H⁺ + 5e⁻ → Mn²⁺ + 4H₂O | Manganese(II) ion | Purple to colorless | 1.51 V [25] |

| Neutral/Weakly Alkaline | MnO₄⁻ + 4H⁺ + 3e⁻ → MnO₂ + 2H₂O | Manganese dioxide (solid) | Purple to brown | 0.59 V [25] |

| Strongly Alkaline | MnO₄⁻ + e⁻ → MnO₄²⁻ | Manganate ion | Purple to green | 0.56 V [25] |

In analytical chemistry, the strongly acidic medium is most commonly employed due to the high oxidizing strength of permanganate (1.51 V) and the clear color change from purple to colorless, which allows KMnO₄ to function as a self-indicator [25] [22]. While sulfuric acid is the preferred acidifying agent, hydrochloric acid is generally avoided because permanganate can oxidize chloride ions (Cl⁻) to chlorine (Cl₂), leading to positive errors [25]. This interference can be mitigated using Zimmermann-Reinhardt's solution, which contains manganese(II) sulfate to lower the oxidation potential of the MnO₄⁻/Mn²⁺ couple, making it a weaker oxidant less likely to attack chloride ions [25].

Experimental Protocol: Standardization of KMnO₄

Potassium permanganate solutions are not primary standards and must be standardized due to the inherent instability of the compound and the common presence of manganese dioxide (MnO₂) in its solutions, which catalyzes decomposition [25]. A standard protocol using sodium oxalate (Na₂C₂O₄) as a primary standard is outlined below [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄): The titrant to be standardized. It is a powerful oxidizing agent [25].

- Sodium Oxalate (Na₂C₂O₄): Primary standard. A pure, stable reducing agent [25].

- Dilute Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄): Provides the strongly acidic medium required for the reaction [25].

Visualization of the Standardization Workflow The following diagram illustrates the key steps involved in the standardization of potassium permanganate solution against sodium oxalate.

Detailed Methodology

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve approximately 3.2 g of KMnO₄ in 1000 mL of distilled water. Heat the solution to boiling and maintain it just below boiling for about an hour, or allow it to stand at room temperature for 2-3 days. This process ages the solution and promotes the decomposition of any reducing impurities. Filter the solution through a sintered-glass crucible to remove solid MnO₂, which otherwise catalyzes the decomposition of permanganate [25]. Store the filtered solution in a dark, amber-colored bottle to protect it from light and reducing vapors [25].

- Titration Procedure: Accurately weigh a dried sample of primary standard sodium oxalate (approximately 0.1 - 0.2 g) into a conical flask. Dissolve it in about 100 mL of dilute sulfuric acid (1 M). Heat the solution to about 60°C; at lower temperatures, the reaction is slow and may lead to the formation of Mn(III) intermediates, causing errors [25]. Titrate the warm solution with the KMnO₄ solution from the burette, with constant swirling. The initial purple color will be decolorized as it reacts. The endpoint is marked by the first persistent pale pink color throughout the solution [25].

- Reaction Stoichiometry: The balanced ionic equation for the reaction is: [ 2MnO4^- + 5C2O4^{2-} + 16H^+ \rightarrow 2Mn^{2+} + 10CO2 + 8H_2O ] Based on this, the equivalent weight of KMnO₄ in acid medium is M/5 [25].

Iodometry

Principle and Distinction from Iodimetry

Iodine-based titrations are classified into two main types: iodometry and iodimetry. This distinction is critical for researchers designing an analytical method.

- Iodimetry: This is a direct titration method. A standardized iodine solution (I₂) is used as a moderate oxidizing agent to directly titrate a strong reducing analyte (e.g., ascorbic acid, sulfites) [25] [26]. The reaction involves the reduction of I₂ to iodide (I⁻).

- Iodometry: This is an indirect titration method used for analyzing oxidizing agents (e.g., Cu²⁺, K₂Cr₂O₇, dissolved oxygen) [25] [1]. The sample containing the oxidizing agent is added to an excess of potassium iodide (KI). The oxidant liberates an equivalent amount of iodine from the iodide. The liberated I₂ is then titrated with a standardized sodium thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) solution [25] [26].

The core reaction in iodometry, between iodine and thiosulfate, is: [ I2 + 2S2O3^{2-} \rightarrow S4O_6^{2-} + 2I^- ] This reaction produces the tetrathionate ion and is the basis for quantification [26]. Starch is used as an indicator, forming an intense blue complex with iodine. It should be added only when the solution is a pale yellow (near the endpoint) to prevent decomposition of the complex and ensure a sharp color change from blue to colorless [22].

Experimental Protocol: Determination of an Oxidizing Agent

This protocol outlines the general steps for using iodometry to quantify an oxidizing agent, such as potassium dichromate.

Research Reagent Solutions

- Potassium Iodide (KI): Source of iodide (I⁻) ions, which are oxidized to I₂ by the analyte [26].

- Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃): The titrant, a reducing agent that reacts with liberated I₂ [26] [1].

- Starch Solution: Indicator that forms a blue complex with I₂ [26] [22].

- Dilute Acid (e.g., H₂SO₄): Often used to acidify the reaction mixture.

Visualization of the Iodometric Workflow The flowchart below depicts the sequential stages of a typical iodometric analysis.

Detailed Methodology

- Liberation of Iodine: Pipette a known volume of the sample solution containing the oxidizing agent into an iodine flask. Add a significant excess of solid or concentrated potassium iodide (KI). Acidify the mixture with dilute sulfuric or hydrochloric acid, if required for the specific reaction. Swirl to mix and allow the reaction to proceed in the dark for a few minutes to ensure complete liberation of iodine. The mixture will typically develop a brown color due to the dissolved I₂.

- Titration: Titrate the liberated iodine with standardized sodium thiosulfate solution with continuous shaking. Continue the titration until the brown color fades to a pale yellow. At this point, add a few milliliters of freshly prepared starch solution. The mixture will turn a deep blue. Continue titrating carefully, drop-wise, until the blue color completely disappears, marking the endpoint. Record the volume of thiosulfate used [26].

- Error Considerations: Two potential sources of error in iodometry are the air oxidation of iodide in acidic media and the volatility of iodine. These can be minimized by conducting the liberation step in a closed vessel, avoiding excessive exposure to air, and ensuring an adequate excess of KI to form the more stable triiodide ion (I₃⁻) [26].

Dichromatometry

Principle and Advantages

Dichromatometry employs potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) as an oxidizing agent in acidic media. The reduction half-reaction is: [ Cr2O7^{2-} + 14H^+ + 6e^- \rightarrow 2Cr^{3+} + 7H_2O ] The standard reduction potential for this couple is +1.33 V, making dichromate a strong but slightly weaker oxidant than permanganate [25].

Despite its lower oxidation potential, potassium dichromate offers several significant advantages as a titrant, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Key Advantages of Potassium Dichromate as a Titrant

| Advantage | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Standard | K₂Cr₂O₇ is available in high purity, is highly stable, and can be used to prepare standard solutions by direct weighing [25]. |

| Solution Stability | Aqueous solutions are stable indefinitely and are not attacked by organic matter or decomposed by light [25]. |

| Selective Oxidation | In cold, dilute HCl solution, it does not oxidize Cl⁻ ions, allowing for the titration of Fe(II) in the presence of HCl without interference [25]. |

A common application is the determination of iron, where Fe²⁺ is oxidized to Fe³⁺, and dichromate is reduced to Cr³⁺, causing a color change from orange to green [25] [23]. Since the color change is not sufficiently sharp for endpoint detection, redox indicators such as N-phenylanthranilic acid or diphenylamine are used [25] [26].

Experimental Protocol: Determination of Iron using Mohr's Salt

This protocol details the use of potassium dichromate to determine the concentration of iron(II) using ferrous ammonium sulfate (Mohr's salt) as the analyte.

Research Reagent Solutions

- Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇): Primary standard titrant and oxidizing agent [25].

- Mohr's Salt (Fe(NH₄)₂(SO₄)₂·6H₂O): Analyte containing Fe²⁺ ions [26].

- Acid (e.g., H₂SO₄): Provides the acidic medium required for the reaction [26].

- Redox Indicator (e.g., N-phenylanthranilic acid): Signals the titration endpoint [26].

Visualization of the Iron Determination Workflow The process for determining iron content using dichromate is illustrated in the following diagram.

Detailed Methodology

- Standard Solution Preparation: Accurately weigh a known amount of pure, dry potassium dichromate. Dissolve it in distilled water and make up to the mark in a volumetric flask to obtain a solution of known molarity. No further standardization is needed [25].

- Sample Preparation and Titration: Dissolve a known weight of the iron-containing sample (e.g., Mohr's salt) in dilute sulfuric acid to prevent the hydrolysis of Fe³⁺ ions. Add a few drops of the chosen redox indicator. Titrate this solution with the standard potassium dichromate solution with constant swirling. The endpoint is marked by a sharp color change specific to the indicator used (e.g., from green to a violet or reddish tint for N-phenylanthranilic acid) [26].

- Reaction Stoichiometry: The overall balanced reaction is: [ Cr2O7^{2-} + 6Fe^{2+} + 14H^+ \rightarrow 2Cr^{3+} + 6Fe^{3+} + 7H_2O ] This shows that 1 mole of K₂Cr₂O₇ reacts with 6 moles of Fe²⁺ [26].

Comparative Analysis and Research Applications

The following consolidated table provides a side-by-side comparison of the three redox titration methods, highlighting their key characteristics to aid in method selection.

Table 3: Comparative Overview of Permanganometry, Iodometry, and Dichromatometry

| Parameter | Permanganometry | Iodometry | Dichromatometry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Titrant | Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃) | Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) |

| Nature of Titrant | Secondary Standard | Secondary Standard | Primary Standard |

| Active Species | MnO₄⁻ | S₂O₃²⁻ (for liberated I₂) | Cr₂O₇²⁻ |

| Typical Medium | Strongly Acidic (H₂SO₄) | Neutral / Slightly Acidic | Acidic |

| Indicator | Self-indicating (KMnO₄) | Starch | Redox Indicator (e.g., N-phenylanthranilic acid) |

| Key Advantage | Strong oxidant, self-indicating | Versatile for many oxidizers | Highly stable, primary standard, non-reactive with Cl⁻ |

| Key Disadvantage | Requires standardization; reacts with Cl⁻ | Multiple steps; potential for I₂ loss | Requires an external indicator |

Applications in Scientific and Industrial Research

These titration methods are cornerstones of quantitative analysis across diverse research fields.

- Pharmaceutical Industry: Iodometry and iodimetry are extensively used for the assay of active pharmaceutical ingredients. A prime example is the determination of Vitamin C (ascorbic acid), a strong reducing agent, either by direct iodimetry or through back-titration methods [22] [24]. Permanganometry can be applied to quantify other organic compounds like formates or oxalates in drug substances [25].

- Environmental Analysis: Dichromatometry is a standard method for determining the Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) of water, a critical parameter for assessing organic pollutant load [7]. Iodometry is employed in the Winkler test for determining dissolved oxygen in water, essential for aquatic health monitoring [24].

- Metallurgy and Material Science: The determination of iron content in ores and alloys is a classic application of both permanganometry and dichromatometry [25] [7]. The choice between methods often depends on the sample matrix, particularly the presence of chloride ions, which favors the use of dichromate.

- Food and Beverage Industry: Redox titrations monitor product quality. Iodometry can assess sulfate levels in wine, while permanganometry or iodometry can determine peroxide values in oils, an indicator of rancidity [24].

Permanganometry, iodometry, and dichromatometry represent three pillars of classical redox titration, each with a unique set of principles, reagents, and applications. Permanganometry offers a powerful, self-indicating system, iodometry provides exceptional versatility for analyzing oxidizing agents, and dichromatometry delivers superior stability and reliability as a primary standard. A deep understanding of their underlying mechanisms, optimal conditions, and potential interferences is paramount for researchers in drug development, environmental science, and industrial chemistry. These methods continue to be vital tools for precise quantitative analysis, forming an essential part of the analytical chemist's toolkit for quality control and research.

Executing Redox Titrations: Protocols and Real-World Applications

Redox titration is a fundamental analytical technique used to determine the concentration of an unknown substance by measuring the electron transfer in a redox (reduction-oxidation) reaction [6]. In this process, a titrant with a known concentration of an oxidizing or reducing agent is gradually added to an analyte until the reaction reaches its endpoint, signaling completion [6]. The technique was first introduced in 1787 by Claude Berthollet for analyzing chlorine water and was later expanded by Joseph Gay-Lussac in 1814 [4] [5]. The development of new titrants such as MnO₄⁻, Cr₂O₇²⁻, and I₂ in the mid-1800s, along with the introduction of the first redox indicator (diphenylamine) in the 1920s, significantly increased the method's applicability [4] [5]. This guide details the complete experimental protocol for determining iron content via redox titration, framed within the broader context of analytical chemistry research for drug development and industrial applications.

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in the redox titration process for iron determination, from sample preparation through final calculation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of redox titration requires precise preparation and understanding of key reagents. The following table details essential materials and their specific functions in the analytical process.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Iron Determination via Redox Titration

| Reagent Name | Chemical Formula | Function & Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Dichromate | K₂Cr₂O₇ | Primary titrant and oxidizing agent; standard solution of known concentration that quantitatively oxidizes Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺ [27]. |

| Stannous Chloride | SnCl₂ | Reducing agent for preliminary reduction; converts Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺ in the first reduction stage, indicated by a color change from brown to light yellow [27]. |

| Titanium Trichloride | TiCl₃ | Powerful reducing agent for secondary reduction; ensures complete reduction of residual Fe³⁺, used in conjunction with sodium tungstrate [27]. |

| Sodium Tungstate | Na₂WO₄ | Indicator for reduction completeness; forms a "tungsten blue" complex when excess Ti³⁺ is present, signaling that all Fe³⁺ has been reduced [27]. |

| Hydrochloric Acid | HCl | Sample dissolution medium; concentrated HCl is used to dissolve iron elements in the ore, converting them into ferric and ferrous chlorides [27]. |

| Potassium Fluoride | KF | Decomplexation agent; added to liberate iron elements encapsulated by silicate compounds in the ore through fluoride complexation with silicon [27]. |

Detailed Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and Pre-Treatment

- Weighing: Accurately weigh a representative sample of the iron ore (mass depends on expected iron content) and transfer it to an appropriate digestion flask.

- Acid Digestion: Add a sufficient volume of concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) to completely dissolve the sample [27]. Gently heat if necessary to accelerate dissolution, ensuring all iron species are solubilized.

- Silicate Decomposition: If the iron ore contains silicate compounds, add potassium fluoride (KF) to the mixture. The fluoride ions will react with silicon through complexation, liberating encapsulated iron elements and ensuring a complete analysis [27].

Reduction Process: Converting Iron to Fe²⁺

For a successful titration, all iron must be in the +2 oxidation state before the main titration begins. This is a two-stage reduction process with visual checkpoints.

Primary Reduction with Stannous Chloride:

- While the dissolved sample solution is still warm, add a stannous chloride (SnCl₂) solution drop-wise with continuous stirring [27].

- Endpoint Checkpoint: The addition is continued until the solution color changes from brown to light yellow, indicating the reduction of the bulk of Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺ [27]. Care must be taken to avoid a large excess of SnCl₂.

Secondary Reduction with Titanium Trichloride:

- Cool the solution. Add sodium tungstate (Na₂WO₄) solution and then add titanium trichloride (TiCl₃) solution drop-wise [27].

- Endpoint Checkpoint: The solution will develop a blue color ("tungsten blue") due to the reduction of tungstate by excess Ti³⁺. This confirms that all Fe³⁺ has been reduced and a slight excess of reducing agent is present [27].

Excess Reductant Elimination:

- The slight excess of Ti³⁺ (responsible for the blue color) must be removed to prevent interference with the subsequent titration.

- Dilute the solution with a small amount of deionized water and expose it to air while stirring. The dissolved oxygen will slowly re-oxize the excess reducing agent, causing the blue color to disappear, leaving a colorless solution ready for titration [27].

Titration and Endpoint Detection

The final and critical phase is the titration of the prepared Fe²⁺ solution with a standard oxidizing agent.

- Titrant Selection and Setup: Potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) is used as the primary titrant [27]. Fill a calibrated burette with the standard K₂Cr₂O₇ solution.

- Titration Execution: Gradually add the K₂Cr₂O₇ titrant to the reduced, colorless analyte solution with constant stirring. The reaction occurring is: Cr₂O₇²⁻ + 6Fe²⁺ + 14H⁺ → 2Cr³⁺ + 6Fe³⁺ + 7H₂O.

- Visual Endpoint Detection: The endpoint is signaled by a sharp color change. In this system, the solution turns from colorless to a permanent purple or violet tint due to the first trace of excess dichromate ions [27]. The volume of titrant used to reach this point is recorded.

Table 2: Color Change Progression During the Redox Titration Stages

| Experimental Stage | Solution Color Before Stage | Solution Color After Stage | Chemical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| After SnCl₂ Addition | Brown | Light Yellow | Bulk reduction of Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺ is complete [27]. |

| After TiCl₃/Na₂WO₄ Addition | Light Yellow | Blue (Tungsten Blue) | Confirmation of complete Fe³⁺ reduction and presence of excess Ti³⁺ [27]. |

| After Excess Reductant Oxidation | Blue | Colorless | Excess Ti³⁺ is oxidized; solution contains only Fe²⁺, ready for titration [27]. |

| At Titration Endpoint | Colorless | Purple/Violet | First appearance of excess K₂Cr₂O₇ titrant, indicating all Fe²⁺ has been oxidized [27]. |

Data Analysis and Calculation

The quantitative determination of iron content is derived from the stoichiometry of the redox reaction and the volume of titrant consumed.

Moles of Titrant: Calculate the moles of potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) used at the endpoint.

- Moles of K₂Cr₂O₇ = Molarity of K₂Cr₂O₇ (mol/L) × Volume used (L)

Moles of Iron: From the reaction stoichiometry (1 mol Cr₂O₇²⁻ reacts with 6 mol Fe²⁺), calculate the moles of iron in the sample solution.

- Moles of Fe = Moles of K₂Cr₂O₇ × 6

Mass and Percentage of Iron:

- Mass of Fe (g) = Moles of Fe × Atomic Mass of Fe (55.845 g/mol)

- Percentage of Fe in sample = (Mass of Fe / Mass of sample) × 100%

Modern automated systems using HSV color model-based visual detection have demonstrated the ability to perform these titrations with high precision, achieving derivation of less than 1% from the certified value for standard iron ores [27].

Advanced Endpoint Detection Techniques

While visual detection is reliable, technological advancements offer greater precision. Automated titration platforms can be implemented with visual detection apparatus based on color sensors and the Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV) color model [27]. In this model:

- Hue (H) and Saturation (S) are particularly effective at collectively capturing the subtle solution color changes during the redox titration process with high sensitivity [27].

- Exact threshold values for H and S can be derived for different titration stages, allowing a computer vision system to replace human judgment for endpoint detection, thereby achieving full process automation and superior accuracy [27].

Permanganometry, a classic redox titrimetric method, utilizes potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) as a powerful oxidizing titrant. This guide details its application in quantifying two key analytes: oxalic acid and hydrogen peroxide, foundational methods in analytical chemistry research and development [4].

Theoretical Foundations of Permanganometry

Potassium permanganate is a versatile oxidizing agent whose application in quantitative analysis dates back to the mid-1800s [4]. In acidic media, it undergoes reduction to pale pink Mn²⁺ ions, providing a self-indicating endpoint through its distinctive color change.

The fundamental reduction half-reaction in acidic solution is: MnO₄⁻ + 8H⁺ + 5e⁻ → Mn²⁺ + 4H₂O

This reaction forms the basis for quantifying reducing agents like oxalic acid and hydrogen peroxide. The equivalent weight of KMnO₄ in this process is one-fifth of its molecular weight. The Nernst equation governs the potential throughout the titration, where the reaction's potential (E_rxn) is the difference between the reduction potentials of the involved half-reactions [4]. Before the equivalence point, the potential is easiest to calculate using the Nernst equation for the titrand's (analyte's) half-reaction; after the equivalence point, the potential is best calculated using the titrant's (KMnO₄'s) half-reaction [4].

Experimental Protocols

Quantification of Oxalic Acid (H₂C₂O₄)

Oxalic acid reduces permanganate in a reaction that is slow at room temperature but is catalyzed by Mn²⁺ and heat.

Underlying Redox Reaction: 2MnO₄⁻ + 5H₂C₂O₄ + 6H⁺ → 2Mn²⁺ + 10CO₂ + 8H₂O

Detailed Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Accurately weigh a pure sample of oxalic acid dihydrate (H₂C₂O₄·2H₂O) and dissolve it in approximately 100 mL of 1M sulfuric acid.

- Titration: Heat the oxalic acid solution to 60-70°C. Titrate with a standardized potassium permanganate solution from a burette with constant swirling.

- Endpoint Determination: The endpoint is the first persistent pale pink color that remains for at least 30 seconds. The heat and the Mn²⁺ produced autocatalyze the reaction.

- Calculation: The moles of oxalic acid are calculated from the titre value using the 2:5 (MnO₄⁻:H₂C₂O₄) stoichiometry of the reaction.

Quantification of Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂)

Hydrogen peroxide acts as a reducing agent in acidic permanganometry, providing a direct and efficient quantification method.

Underlying Redox Reaction: 2MnO₄⁻ + 5H₂O₂ + 6H⁺ → 2Mn²⁺ + 5O₂ + 8H₂O

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Dilution: Dilute the hydrogen peroxide sample solution with distilled water. Add approximately 100 mL of 1M sulfuric acid to the aliquot.

- Titration: Titrate the cold, acidified solution with the standardized potassium permanganate solution with gentle swirling.

- Endpoint Determination: The endpoint is the first permanent pale pink color. The reaction proceeds rapidly at room temperature.

- Calculation: The concentration of H₂O₂ is determined from the titre using the 2:5 (MnO₄⁻:H₂O₂) stoichiometric relationship.

Data Presentation and Calculation

The following tables summarize the standard experimental parameters and an example calculation for these determinations.

Table 1: Standard Titration Parameters

| Parameter | Oxalic Acid Determination | Hydrogen Peroxide Determination |

|---|---|---|

| Typical KMnO₄ Concentration | 0.02 - 0.1 M | 0.02 - 0.1 M |

| Acid Used | 1 M H₂SO₄ | 1 M H₂SO₄ |

| Temperature | 60 - 70 °C | Room Temperature |

| Stoichiometry (KMnO₄:Analyte) | 2:5 | 2:5 |

| Endpoint Color | Persistent Pale Pink | Persistent Pale Pink |

Table 2: Example Calculation for Oxalic Acid Quantification

| Calculation Step | Value & Formula |

|---|---|

| KMnO₄ Concentration | 0.0502 M |

| Average Titre Volume | 24.35 mL |

| Moles of KMnO₄ | 0.0502 mol/L × 0.02435 L = 1.222 × 10⁻³ mol |

| Moles of H₂C₂O₄ | (5/2) × 1.222 × 10⁻³ mol = 3.055 × 10⁻³ mol |

| Mass of H₂C₂O₄·2H₂O | 3.055 × 10⁻³ mol × 126.07 g/mol = 0.3851 g |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Permanganometric Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function & Role in the Analysis |

|---|---|