Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer: Validation Methods, Mechanistic Insights, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists on validating inner-sphere (ISET) and outer-sphere (OSET) electron transfer pathways.

Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer: Validation Methods, Mechanistic Insights, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists on validating inner-sphere (ISET) and outer-sphere (OSET) electron transfer pathways. It covers foundational concepts, including the defining role of bridging ligands in ISET and the solvent-mediated nature of OSET. The content explores advanced methodological approaches like DFT calculations and Marcus theory analysis for pathway discrimination. It further addresses practical challenges in troubleshooting catalytic cycles and optimizing reaction outcomes, using contemporary examples from photoredox catalysis and electrocatalysis. Finally, it presents a framework for the comparative validation of electron transfer mechanisms, highlighting implications for drug development and sustainable chemistry.

Core Principles: Defining Inner-Sphere and Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer Mechanisms

The conceptual distinction between inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer mechanisms represents a foundational principle in inorganic chemistry and bioinorganic processes. This guide objectively compares these competing electron transfer pathways through the lens of Henry Taube's seminal experiment, which provided definitive validation for the inner-sphere mechanism involving bridging ligands. We present comprehensive experimental data, detailed methodologies, and structural visualizations that elucidate how bridging ligands serve as conductive pathways between metal centers, enabling direct electron transfer through covalent bridges as opposed to the through-space electron jumping characteristic of outer-sphere reactions. The critical evidence from Taube's experiment, which demonstrated direct ligand transfer between metal centers, established a paradigm that continues to inform modern research in catalysis, materials science, and medicinal chemistry.

Electron transfer reactions constitute a fundamental class of chemical processes in which a single electron is transferred from one molecular species to another [1]. In transition metal chemistry, these reactions are mechanistically categorized into two distinct pathways: inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer. The core distinction between these mechanisms lies in whether the participating metal centers become connected by a shared ligand during the electron transfer event.

The inner-sphere mechanism proceeds via a covalent linkage—a bridging ligand that connects the oxidant and reductant metal centers during the electron transfer event [2]. This bridging ligand, typically denoted with the Greek prefix "μ-" to indicate its connective role, forms simultaneous bonds to both metal centers, creating a direct conduit for electron passage between them [3]. In contrast, the outer-sphere mechanism occurs between chemical species that remain separate and intact before, during, and after the electron transfer, with the electron moving through space from one redox center to the other without the formation of any covalent bridge [4].

The theoretical framework for understanding electron transfer rates was pioneered by Rudolph A. Marcus, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1992 for his theory describing the rates of outer sphere electron transfer reactions [1] [4]. Marcus theory establishes that electron transfer rates depend on both the thermodynamic driving force (the difference in redox potentials) and the reorganizational energy (the energy required to adjust molecular geometries and solvent orientations between reactant and product configurations) [4].

The Bridging Ligand Concept

Definition and Fundamental Characteristics

In coordination chemistry, a bridging ligand is defined as an atom or polyatomic entity that binds simultaneously to two or more metal centers, thereby connecting them to form polynuclear complexes [3]. These ligands donate electron pairs to multiple metal centers through one or more donor atoms, distinguishing them from terminal ligands that coordinate to only one metal center [3]. The bridging capability of a ligand depends critically on its electronic properties and coordination geometry, with small anions typically proving most effective for creating stable bridges between metals.

Bridging ligands are formally denoted in chemical nomenclature using the prefix "μ-" (Greek mu), with a subscript indicating the number of central metal atoms bridged—for instance, μ₂ for a ligand connecting two metals or μ₃ for three [3]. This notation system was codified by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) to standardize the description of polynuclear coordination compounds [3].

Classification of Common Bridging Ligands

Bridging ligands encompass a diverse array of chemical species that can be categorized based on their donor atoms and structural properties. The table below summarizes key bridging ligands and their characteristic features:

Table 1: Common Bridging Ligands and Their Properties

| Ligand | Chemical Formula | Donor Atom(s) | Typical Metals Bridged | Bridge Geometry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorido | Cl⁻ | Cl | Early transition metals (e.g., Nb, Ta) | Bent, μ₂ |

| Hydroxo | OH⁻ | O | First-row transition metals (e.g., Fe, Cr) | Bent, μ₂ |

| Oxido | O²⁻ | O | Transition metals (e.g., Ti, Zr) | Linear or bent, μ₂, μ₃ |

| Cyanido | CN⁻ | C, N | Iron, cobalt | Linear, μ₂ |

| Thiocyanato | SCN⁻ | S, N | Nickel, copper | End-on or end-to-end, μ₂ |

| Azido | N₃⁻ | N | Cobalt, manganese | End-to-end, μ₂ |

| Carbonyl | CO | C, O | Iron, ruthenium | Bent, μ₂ |

| Carboxylato | RCOO⁻ | O | Copper, molybdenum | syn-syn bidentate, μ₂ |

The bridging mode adopted by a ligand significantly influences the electronic coupling between metal centers. The simplest and most prevalent mode is μ₂, where the ligand coordinates to exactly two metal atoms in an edge-bridging configuration that forms a diamond-shaped core with alternating metal and ligand positions [3]. Higher-order bridging modes, such as μ₃, involve the ligand coordinating to three metal centers, commonly in a facial capping fashion over a triangular metal face in cluster compounds [3].

Historical Context: The Taube Experiment

Experimental Design and Rationale

In the 1950s-1960s, Henry Taube of Stanford University designed a series of elegant experiments to elucidate the mechanism of electron transfer between coordination complexes. His investigation was motivated by puzzling observations of significant rate enhancements in certain electron transfer reactions when halide ligands were present in the coordination sphere [5]. Taube noted striking differences in reaction kinetics between two seemingly similar electron transfer processes:

Table 2: Kinetic Data Highlighting the Bridging Ligand Effect

| Reaction | Rate Constant (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Observation |

|---|---|---|

| [Co(NH₃)₆]³⁺ + [Cr(H₂O)₆]²⁺ → Co²⁺ + Cr³⁺ + 6NH₃ | 10⁻⁴ | No ligand transfer |

| [Co(NH₃)₅Cl]²⁺ + [Cr(H₂O)₆]²⁺ → Co²⁺ + [CrCl(H₂O)₅]²⁺ + 5NH₃ | 6×10⁵ | Chloride transfer to Cr |

The dramatic rate enhancement (by a factor of approximately 10⁹) when a chloride ligand was present, coupled with the observation that the chloride originally bonded to cobalt became attached to chromium in the product, suggested a fundamentally different mechanism was operative [5].

Critical Experimental Evidence

Taube's definitive experiment involved reducing [Co(NH₃)₅Cl]²⁺ with [Cr(H₂O)₆]²⁺ in a medium containing radioactive chloride ions (³⁶Cl⁻) [2]. The crucial finding was that less than 0.5% of the chloride attached to the resulting Cr(III) product exchanged with the radioactive chloride in solution [2]. This demonstrated that transfer of Cl from the oxidizing agent (Co(III)) to the reducing agent (Cr(II)) was direct, without dissociation into the solution.

The experiment provided compelling evidence for the formation of a bimetallic transition complex [(NH₃)₅Co(μ-Cl)Cr(H₂O)₅]⁴⁺, wherein the chloride served as a bridge between cobalt and chromium. This bridging chloride acted as a conduit for electron flow from Cr(II) to Co(III), resulting in the formation of Cr(III) and Co(II) products [2]. The experimental workflow and electron transfer pathway can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer Mechanism

For his pioneering work in establishing the inner-sphere electron transfer mechanism, Henry Taube was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1983 [5].

Comparative Analysis: Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Mechanisms

Structural and Mechanistic Comparisons

The fundamental distinction between inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer mechanisms lies in their structural requirements and pathways for electron movement. The following table provides a systematic comparison of their defining characteristics:

Table 3: Mechanism Comparison: Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer

| Characteristic | Inner-Sphere Mechanism | Outer-Sphere Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Bridge Requirement | Requires suitable bridging ligand | No bridging ligand required |

| Metal Centers | Connected by covalent bridge during ET | Remain separate throughout ET |

| Ligand Transfer | Common (as in Taube's experiment) | Never occurs |

| Substitution Lability | Requires at least one labile complex | Can proceed with inert complexes |

| Electron Pathway | Through bridging ligand | Through space between coordination spheres |

| Distance Dependence | Moderately distance-sensitive | Strongly distance-sensitive |

| Rate Constants | Can be very fast (>10⁵ M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Typically slower for comparable systems |

| Structural Reorganization | Significant bond formation/cleavage | Minimal structural change |

Structural Implications for Electron Transfer Efficiency

The nature of the bridging ligand profoundly influences the efficiency of inner-sphere electron transfer. Bridging ligands facilitate electronic coupling between metal centers through their molecular orbitals, effectively mediating superexchange interactions [6]. Computational studies have demonstrated that substitutions in the bridging ligand can dramatically affect magnetic exchange interactions between metal centers, with the bridging geometry (bond distances and angles) playing a decisive role in determining electron transfer efficiency [6].

In organometallic systems, the electronic properties of bridging ligands (σ-donor and π-acceptor capabilities) significantly influence metal-metal distances and consequently affect electron coupling between centers [7]. For instance, in Fe₂(CO)₉ derivatives, systematic substitution of bridging CO ligands with groups of different donor/acceptor characteristics resulted in Fe-Fe distance variations of up to 52.3 pm, directly impacting the electronic communication between iron centers [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Electron Transfer Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Electron Transfer Research |

|---|---|

| [Co(NH₃)₅Cl]²⁺ (Cobalt pentammine chloride) | Oxidizing agent in Taube experiment; source of transferable chloride bridge |

| [Cr(H₂O)₆]²⁺ (Chromium(II) hexaaqua) | Reducing agent in Taube experiment; labile complex for bridge formation |

| Halide ions (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) | Common bridging ligands for inner-sphere electron transfer |

| Pseudohalides (CN⁻, SCN⁻, N₃⁻) | Versatile bridging ligands with multiple donor atoms |

| Radioactive isotopes (³⁶Cl⁻) | Tracers for establishing ligand transfer pathways |

| Polynuclear complexes (e.g., Fe₂(CO)₉) | Model systems for studying bridging ligand effects |

The bridging ligand concept, decisively validated through Taube's elegant experiment, represents a cornerstone of modern inorganic chemistry that continues to enable sophisticated applications across diverse scientific disciplines. The critical distinction between inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer mechanisms—with the former requiring a covalent bridge between reacting centers—has proven essential for understanding and designing electron transfer processes in synthetic systems, biological enzymes, and functional materials. Taube's experimental approach, combining kinetic measurements with clever tracer methodology, established an enduring paradigm for mechanistic investigation in coordination chemistry. Contemporary research continues to leverage the fundamental principles of bridge-mediated electron transfer in developing advanced catalytic systems, molecular electronic devices, and therapeutic agents whose function depends on controlled electron movement between metal centers.

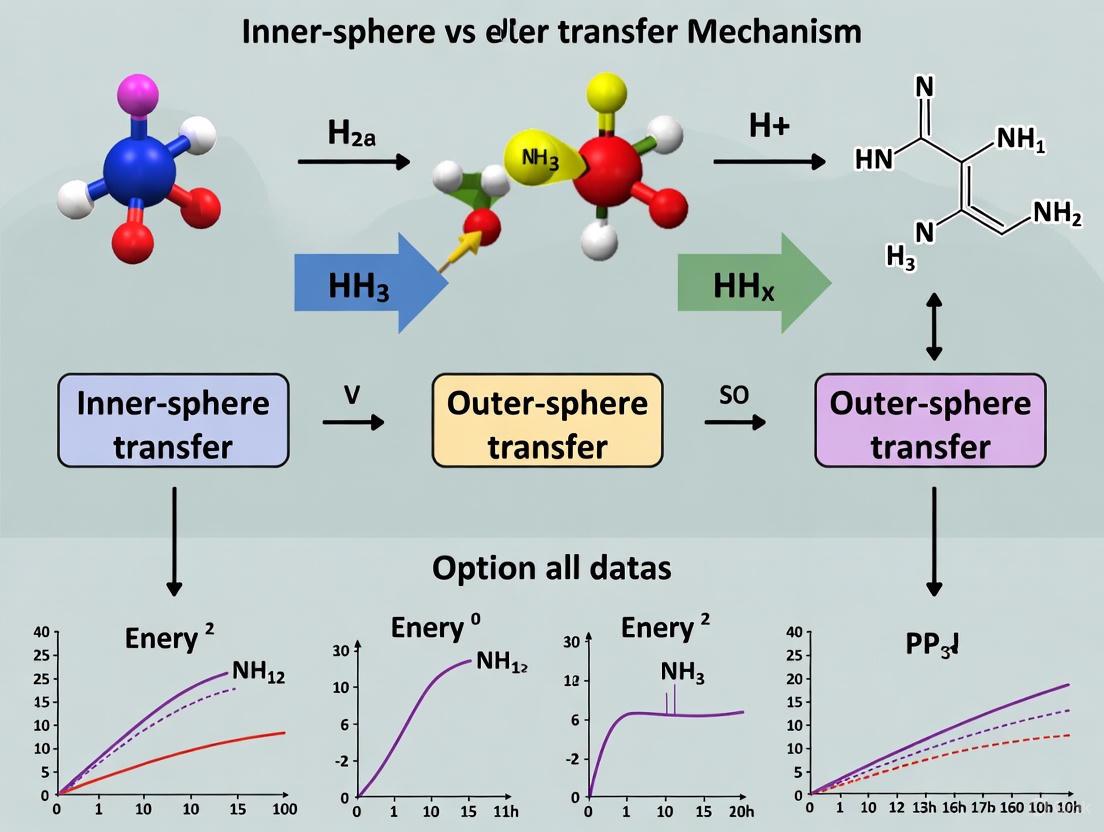

This guide compares the defining experimental characteristics of inner-sphere (IS) and outer-sphere (OS) electron transfer (ET) mechanisms, providing a framework for their validation in chemical and biological systems. The distinction is critical for researchers designing catalysts, interpreting reaction kinetics, or developing electrochemical applications.

Comparative Analysis of ET Mechanisms

The fundamental distinction between IS and OS ET lies in whether the reacting species form a direct, chemically bridged intermediate. The experimental signatures arising from this difference are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Experimental Differentiators for ET Mechanisms

| Differentiating Factor | Inner-Sphere ET | Outer-Sphere ET |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand Participation | Active/Cooperative: Requires a bridging ligand that is directly involved in the ET event, often leading to bond breaking/forming [1]. | Passive/Spectator: Ligands remain coordinated to their original metal center and are not directly involved in the ET pathway [1] [4]. |

| Structural Change | Significant: Involves notable reorganization of the metal-ligand bonds, especially for the bridging ligand; changes in coordination geometry are common [1] [8]. | Minimal: Limited to small adjustments in bond lengths and angles; the primary reorganization involves the solvent shell [1] [4]. |

| Solvent Role | Secondary: The solvent's role is often indirect, solvating the complex but not directly mediating the electron's path [1]. | Primary/Coupled: The solvent shell reorganizes in concert with ET. Motions of solvent molecules (e.g., H-bond rearrangement in water) are directly coupled to the reaction coordinate [9] [10]. |

| Kinetic Evidence | Reaction rates show a strong dependence on the chemical identity and lability of the potential bridging ligand [1]. | Rates are effectively modeled by Marcus Theory, correlating with the thermodynamic driving force and reorganizational energy [1] [4]. |

| Representative Example | ET between two metal complexes via a µ-chloro bridge [1]. | Self-exchange reactions like [MnO4]− + [Mn*O4]2− or ET in iron-sulfur proteins where clusters remain separate [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Validation

Validating an ET mechanism requires a combination of kinetic, spectroscopic, and structural techniques. The following table outlines key experimental approaches and the specific data that distinguishes each mechanism.

Table 2: Key Experiments for Discriminating ET Mechanisms

| Experimental Protocol | Methodology & Key Measurements | Data Interpretation for Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Analysis & Marcus Theory | Measure ET rates as a function of thermodynamic driving force (ΔG°). Calculate the reorganizational energy (λ) [1] [4]. | OS ET typically fits the Marcus equation, potentially showing an "inverted region." IS ET often deviates due to concomitant bond breaking/forming [1]. |

| Bridge Dependence Studies | Systematically vary the identity of potential bridging ligands between donor and acceptor and measure the resulting ET rates [1]. | A dramatic change in rate with different bridging ligands is a hallmark of an IS mechanism. An OS mechanism should be largely insensitive to this change [1]. |

| Ultrafast Solvent Dynamics | Use femtosecond X-ray scattering or spectroscopy to track the motion of solvent molecules during and immediately after photoinduced ET [9] [10]. | For OS ET, solvent reorganization (e.g., water moving ~0.1 Å) is directly coupled to the ET event on a femtosecond timescale. This is less critical for IS ET [10]. |

| Spin State Characterization | Use techniques like EPR spectroscopy to monitor the spin state of a transition metal catalyst before and during the reaction [11]. | A change in spin state induced by axial ligand coordination can lower the energy barrier for SET, providing a pathway for controllable radical initiation [11]. |

| Intermediate Trapping | Employ techniques like ambient mass spectrometry (AMS) with radical traps (e.g., TEMPO) or low temperatures to identify short-lived intermediates [11]. | Detection of a bridged binuclear complex is direct evidence for an IS pathway. The absence of such an intermediate supports, but does not prove, an OS mechanism [1] [8]. |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Mechanistic Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the general experimental workflow for distinguishing ET mechanisms and the specific role of solvent in an OS process.

Experimental Workflow for ET Mechanism Validation

Solvent Reorganization in Outer-Sphere ET

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Electron Transfer Mechanisms

| Reagent / Material | Function in ET Research |

|---|---|

| Redox-Active Ligands (e.g., DHBQ, azo, diimine) [12] [13] | Act as "electron reservoirs," participating directly in multi-electron transfers and enabling metal-ligand cooperative catalysis. |

| Transition Metal Complexes (e.g., Fe(III)-porphyrin, Ru-ammine, Co-bipyridyl) [12] [11] [4] | Serve as tunable electron donors/acceptors. Their redox potentials and coordination geometry can be systematically modified. |

| Chemical Traps (e.g., TEMPO, DMPO) [11] | Used in EPR or MS studies to intercept and stabilize short-lived radical intermediates for identification. |

| Ultrafast Light Sources (e.g., X-ray Free Electron Lasers) [9] [10] | Enable femtosecond-resolution scattering and spectroscopic measurements to capture atomic motions during ET. |

| Computational Chemistry Software (e.g., NWChem) [9] [14] | Models ET pathways, calculates reorganizational energies, and simulates coupled solvent-solute dynamics. |

Electron transfer (ET) reactions are fundamental processes in chemical synthesis, energy conversion, and biological systems. These reactions are broadly classified into two distinct mechanisms: inner-sphere electron transfer (ISET) and outer-sphere electron transfer (OSET). In ISET processes, electron transfer occurs through a shared ligand or bridging molecule that connects the donor and acceptor, often involving direct orbital overlap and chemical bond formation/breaking. In contrast, OSET reactions proceed without direct contact between reactants, with electron transfer occurring through space or solvent molecules. Understanding the kinetic advantages of inner-sphere pathways is crucial for designing more efficient catalytic systems across diverse fields including electrocatalysis, photocatalytic energy conversion, and enzymatic processes. This guide provides a comparative analysis of ISET and OSET reaction kinetics, supported by experimental data and methodologies from recent research, to validate the conditions under which inner-sphere pathways provide significant rate enhancements.

Fundamental Principles of Electron Transfer Pathways

Distinguishing Inner-Sphere and Outer-Sphere Mechanisms

The terminology of inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer originated from studies of homogeneous transition metal complex reactions before being extended to heterogeneous electrochemical processes [15]. In inner-sphere electron transfer (ISET), the reactant forms an intimate contact with the electrode surface, often through specific chemical adsorption, where a central metal atom, bridging molecule, or ligand is in direct contact with the electrode surface. This direct interaction facilitates electron transfer through orbital overlap and typically involves bond formation/breaking processes. Conversely, outer-sphere electron transfer (OSET) occurs when the reactant remains in the outer Helmholtz plane (OHP), separated from the electrode by a solvent layer, with electron transfer proceeding via tunneling without chemical bond formation [15].

The critical distinction lies in the nature of the interaction: OSET systems are generally impervious to surface modifications and chemical environment, while ISET processes are highly sensitive to surface chemistry, specific adsorption, and the presence of functional groups or surface oxides [15]. This fundamental difference manifests dramatically in their reorganization energies and subsequent reaction kinetics, as explored in the following sections.

Theoretical Frameworks: Marcus Theory and Reorganization Energy

Marcus theory provides a fundamental framework for understanding electron transfer kinetics, defining the relationship between the electron transfer rate constant (k) and the reorganization energy (λ) according to the equation:

[ k = A \exp\left[-\frac{(\Delta G^\circ + \lambda)^2}{4\lambda k_B T}\right] ]

where ΔG° represents the standard free energy change, λ denotes the reorganization energy, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature [16]. The reorganization energy (λ) encompasses both internal (molecular vibrations) and external (solvent reorganization) components that represent the energy required to reorganize the molecular structure and solvation environment to reach the transition state.

The entatic state principle further elucidates how systems can achieve accelerated electron transfer rates. This concept proposes that when a metal center is constrained in a geometry intermediate between its preferred oxidation states, both oxidation states become energized, thereby lowering the kinetic barrier between them [16]. Recent model systems demonstrate an exponential correlation between internal reorganization energy and electron transfer rate, where minimal structural rearrangement upon electron transfer leads to dramatically enhanced kinetics [16].

Comparative Kinetic Analysis: Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Pathways

Quantitative Kinetic Comparison of ET Pathways

Table 1: Comparative Kinetic Parameters for Inner-Sphere and Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer Pathways

| Reaction System | Electron Transfer Pathway | Reorganization Energy (λ) | Activation Barrier (eV) | Rate Constant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂ Reduction (No cations) | OS-ET | Not reported | 1.21 eV | Not reported |

| CO₂ Reduction (K⁺ present) | IS-ET | Not reported | 0.61 eV | Not reported |

| CO₂ Reduction (Li⁺ present) | IS-ET | Not reported | 0.91 eV | Not reported |

| Cu(TMG2Phqu)²⁺/⁺ | Entatic State Model | Low internal λ | Not reported | ~10⁵ M⁻¹s⁻¹ |

| Traditional Cu complexes | Non-Entatic | High internal λ | Not reported | 10³-10⁶ M⁻¹s⁻¹ |

The data in Table 1 illustrates consistent kinetic advantages for inner-sphere pathways across diverse reaction systems. The most dramatic evidence comes from electrocatalytic CO₂ reduction, where pathway modulation by alkali metal cations creates distinct kinetic regimes [17]. Without cations, only the OS-ET pathway is feasible with a substantially higher activation barrier (1.21 eV). Introducing cations promotes IS-ET through explicit cation-intermediate coordination, significantly reducing activation barriers to 0.61 eV with K⁺ and 0.91 eV with Li⁺ [17]. This represents a 40-50% reduction in the kinetic barrier for the IS-ET pathway compared to OS-ET.

Similar principles operate in molecular model systems. Copper entatic state complexes engineered for minimal structural rearrangement between oxidation states achieve remarkably fast electron self-exchange rates on the order of 10⁵ M⁻¹s⁻¹ [16]. The exponential relationship between internal reorganization energy and electron transfer rate in these systems confirms the fundamental Marcus theory prediction that minimizing λ dramatically enhances kinetics [16].

Structural and Electronic Factors Governing Pathway Efficiency

Table 2: Structural and Electronic Factors Influencing ISET and OSET Efficiency

| Factor | Impact on ISET | Impact on OSET | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Surface Chemistry | High sensitivity to surface oxides, functional groups | Minimal sensitivity | Hexacyanoferrate ET varies with surface oxygen content [15] |

| Cation Effects | Strong promotion via coordination bonds | Inhibits by increasing barrier | K⁺ reduces CO₂ IS-ET barrier by 0.6 eV [17] |

| Spatial Confinement | Enhanced rates through pre-organization | Minimal effect | Zeolite supercages enhance ET via V-O-Si bonds [18] |

| Orbital Alignment | Critical for direct orbital overlap | Less critical | Reactive orbital forces guide nuclear motions [19] |

| Electronic Structure | Electrode DOS affects reorganization energy | Electrode DOS only affects accessible channels | Graphene doping tunes λ by modulating image potential [20] |

The factors summarized in Table 2 demonstrate that ISET processes can be strategically optimized through multiple complementary approaches. Recent work has revealed that the electronic structure of electrodes plays a central role in governing reorganization energy, contrary to the conventional view that only electrolyte-phase factors determine λ [20]. By tuning the density of states (DOS) in graphene electrodes through electrostatic doping, researchers demonstrated strong modulation of reorganization energy associated with image potential localization, thereby providing a new dimension for controlling ISET kinetics [20].

Spatial confinement represents another powerful strategy for enhancing ISET kinetics. In zeolite-encapsulated V,S-doped carbon dot systems, the formation of V-O-Si bonds between the active center and zeolite framework creates efficient interfacial charge transfer channels, enabling a 5.66-fold enhancement in ammonia production compared to unconfinement systems [18]. This pre-organization of reactants in constrained environments reduces reorganization energy and aligns reactive orbitals optimally for electron transfer.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Probing Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer Routes with Redox Probes

Purpose: To characterize inner-sphere electron transfer routes on catalyst surfaces using classical redox molecular probes [18].

Materials:

- Zeolite 13X framework (1.0 g)

- V,S-doped carbon dots (VS-CDs, 50 mg)

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, 15 mL)

- Ethylene glycol (EG, 55 mL)

- Vanadium(IV)oxyacetylacetonate (1 mmol, 265.1 mg)

- Thiourea (3 mmol, 228.4 mg)

Procedure:

- Encapsulation of Active Components: Combine zeolite 13X with synthesized VS-CDs via impregnation method to create VS-13X composite catalysts.

- Structural Characterization: Perform transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to confirm interpolation of carbon dots within zeolite grain stacking.

- Bond Formation Analysis: Employ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to verify formation of V-O-Si(Al) bonds between VS-CDs and zeolite framework.

- Electron Transfer Assessment: Use inner-sphere redox probes to trace electron transfer routes, confirming zeolite pores function as current collectors by effectively capturing photogenerated electrons [18].

Key Considerations: The V-O-Si bonds create efficient charge transfer channels that provide an electron-rich environment for substrate activation. The acidic sites in the zeolite framework are crucial for forming strong interactions with the encapsulated active components.

Protocol 2: Constrained DFT for Outer-Sphere ET Barrier Calculation

Purpose: To compute outer-sphere electron transfer kinetics and barriers using constrained density functional theory molecular dynamics (cDFT-MD) [17].

Materials:

- DFT simulation software with constrained dynamics capabilities

- Explicit solvation models

- Cation parameters (K⁺, Li⁺ for comparative studies)

Procedure:

- System Setup: Construct simulation cell with electrode surface, explicit solvent molecules, and reactant species (e.g., CO₂).

- Diabatic State Definition: Utilize cDFT to construct charge-localized diabatic states for the reactant and product species.

- Reorganization Energy Calculation: Apply Marcus theory framework using cDFT-MD simulations to parameterize the reorganization energy and electronic coupling matrix elements.

- Kinetic Parameter Extraction: Compute the reaction kinetics along the reorganization coordinate using the Marcus theory formalism [17].

Key Considerations: This method is essential for studying OS-ET processes where conventional geometric reaction coordinates and standard DFT methods cannot accurately capture the solvent reorganization coordinate or the required diabatic states. The cDFT approach properly describes the non-adiabatic character of OS-ET reactions.

Protocol 3: Slow-Growth DFT-MD for Inner-Sphere ET Kinetics

Purpose: To investigate inner-sphere electron transfer thermodynamics and kinetics using slow-growth density functional theory molecular dynamics (SG-DFT-MD) [17].

Materials:

- DFT software with molecular dynamics and enhanced sampling capabilities

- Explicit interface models including electrode, solvent, and cations

- Au(110) surface model for electrocatalytic studies

Procedure:

- Interface Construction: Build electrode-electrolyte interface model with ~2.3M cation concentration at the interface.

- Reaction Pathway Sampling: Employ slow-growth DFT-MD to simulate the adiabatic IS-ET process along a defined geometric reaction coordinate.

- Free Energy Profile Calculation: Obtain the potential of mean force and extract activation barriers for the IS-ET process.

- Cation Coordination Analysis: Monitor explicit coordination bonds between reaction intermediates and partially desolvated cations during the ET process [17].

Key Considerations: The SG-DFT-MD approach is suitable for IS-ET processes where the reaction follows an adiabatic pathway with strong electronic coupling. The method captures the explicit cation effects that arise from short-range chemical interactions rather than long-range electrostatic effects.

Visualization of Electron Transfer Pathways and Kinetics

Diagram 1: Electron Transfer Pathways and Kinetic Outcomes. Inner-sphere pathways (green) enable reduced reorganization energies and activation barriers through specific chemical interactions, leading to accelerated kinetics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Electron Transfer Pathways

| Reagent/Material | Function in ET Studies | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hexacyanoferrate II/III | Redox probe for surface-sensitive ET characterization | Distinguishing ISET vs OSET based on surface dependence [15] |

| Ru(NH₃)₆³⁺/²⁺ | Outer-sphere redox couple reference | Electrode DOS tuning studies [20] |

| Zeolite 13X | Confinement matrix for pre-organizing reactants | Enhancing ISET through V-O-Si bond formation [18] |

| Alkali Metal Cations (K⁺, Li⁺) | ISET promoters through coordination bonds | Lowering CO₂ reduction barriers [17] |

| TMGqu Ligand Systems | Entatic state model complexes | Studying reorganization energy-ET rate relationships [16] |

| VS-CDs (V,S-doped Carbon Dots) | Active catalytic centers with tunable electronic structure | Nitrogen reduction reaction studies [18] |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that inner-sphere electron transfer pathways consistently provide substantial kinetic advantages over outer-sphere mechanisms across diverse chemical systems. The key unifying principle emerges from the ability of ISET processes to minimize reorganization energy through specific chemical interactions, including cation coordination, surface bonding, and spatial confinement. Experimental methodologies ranging from redox probe characterization to advanced computational simulations provide robust tools for distinguishing these pathways and quantifying their kinetic parameters. The continued refinement of entatic state model systems and electrode materials with tuned electronic densities of states offers promising avenues for further enhancing electron transfer rates in both synthetic and biological systems.

The Role of Solvent Reorganization Energy in Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer

Electron transfer (ET) reactions are fundamental processes in chemistry and biology, underpinning energy conversion, catalytic cycles, and numerous biological functions. Within this domain, a critical distinction exists between inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer mechanisms. Outer-sphere ET occurs between chemical species that remain separate and intact before, during, and after the electron jump, with no shared ligand or chemical bridge facilitating the process [4]. This is in contrast to inner-sphere ET, where the participating redox sites become connected by a chemical bridge during the transfer.

The theoretical framework for understanding these reactions was pioneered by Rudolph A. Marcus. Marcus theory explains that the rate of outer-sphere ET depends not only on the thermodynamic driving force but also inversely on the "reorganization energy" (λ) [21]. This energy represents the penalty required to distort the atomic configuration and solvation environment of the reactant species to resemble those of the product state prior to the electron jump [20]. The total reorganization energy (λ) comprises two components: the inner-sphere λ, associated with changes in bond lengths and angles within the reactants themselves, and the outer-sphere λ, which originates from the rearrangement of the solvent molecules surrounding the reactants [21].

This guide objectively compares the role of solvent reorganization energy in different experimental systems, focusing on its decisive influence on ET rates and catalytic outcomes. By presenting quantitative data and detailed methodologies, we aim to provide researchers and scientists with a clear framework for validating outer-sphere mechanisms and differentiating them from inner-sphere pathways.

Theoretical Framework: Marcus Theory and Reorganization Energy

Marcus theory provides a microscopic framework for understanding the activation free energy of electron transfer reactions. The key equation for the activation free energy (ΔG‡) is:

ΔG‡ = (λ + ΔG°)² / 4λ

Where ΔG° is the standard Gibbs free energy change of the reaction, and λ is the total reorganization energy [21]. The classical Marcus model treats the solvent as a dielectric continuum. When an electron transfers, the solvent polarization must reorganize to accommodate the new charge distribution. However, because the electron is an elementary particle that moves much faster than the heavy solvent nuclei, the electron jump can only occur when thermal fluctuations create a solvent configuration where the energies of the precursor and successor states are equal, without any change in nuclear coordinates—a consequence of the Franck-Condon principle [21]. The energy required to achieve this "transition state" solvent configuration is the solvent reorganization energy.

The following diagram illustrates the free energy surfaces and critical parameters governing outer-sphere electron transfer as described by Marcus theory.

- Illustration of the free energy surfaces for electron transfer. The parabolic curves represent the free energy of the precursor (reactants, blue) and successor (products, red) complexes as functions of the solvent polarization coordinate. The activation free energy (ΔG‡) is determined by the total reorganization energy (λ) and the reaction free energy (ΔG°). The electron transfer event occurs at the intersection point of the two parabolas.

In outer-sphere ET, the solvent reorganization energy often constitutes the dominant contribution to the total λ, as the reactants themselves undergo minimal structural change. This is particularly true for biological ET systems, where redox centers are frequently separated by large distances (up to ~11 Å) within a protein matrix [4].

Comparative Analysis of Model Systems

To validate the role of solvent reorganization energy in outer-sphere ET, we compare three key experimental systems: a classic inorganic self-exchange reaction, a tunable electrode-electrolyte interface, and a pair of designed artificial metalloenzymes. The quantitative data summarizing their reorganization energies and ET properties are presented in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Electron Transfer Parameters Across Model Systems

| System Description | Total Reorganization Energy (λ) | Solvent Reorganization Contribution | Key Experimental Techniques | Electron Transfer Rate / Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial Cu Protein (3SCC) [22] [23] | Lower λ | Minor contributor | EPR, electronic spectroscopy, electrochemistry, kinetics | Active C-H oxidation catalysis; rapid reaction with H₂O₂ |

| Artificial Cu Protein (4SCC) [22] [23] | High λ (initially) | Dominant contributor, mediated by His---Glu H-bond & H₂O network | EPR, electronic spectroscopy, electrochemistry, kinetics, X-ray crystallography | Inactive toward C-H peroxidation; slower ET |

| Artificial Cu Protein (Engineered 4SCC) [22] [23] | Lower λ (after H-bond disruption) | Significantly reduced | EPR, electrochemistry, kinetics | C-H peroxidation activity restored |

| [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺ at Graphene Electrodes [20] | Tunable λ | Major contributor, modulated by electrode DOS | Scanning Electrochemical Cell Microscopy (SECCM), cyclic voltammetry | ET rate varies significantly with graphene charge carrier density |

| [Co(bipy)₃]²⁺/³⁺ Self-Exchange [4] | Moderate λ | Presumed significant | Kinetic measurement of self-exchange rate | 18 M⁻¹s⁻¹ |

Artificial Copper Proteins (ArCuPs)

A seminal 2025 study provides direct experimental evidence of how controlled changes to the outer coordination sphere dictate solvent reorganization and catalytic function [22] [23]. Researchers designed two artificial copper proteins:

- 3SCC: A trimeric assembly with a trigonal Cu(His)₃ active site.

- 4SCC: A tetrameric assembly with a square pyramidal Cu(His)₄(OH₂) active site, modeling the CuB site of particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO).

The experimental data revealed a stark functional difference: while 3SCC electrocatalyzes C-H oxidation, 4SCC does not [22]. This inactivity was traced to a significantly higher total reorganization energy in 4SCC, which was overwhelmingly dominated by the solvent reorganization energy component. X-ray crystallography revealed that a specific His---Glu hydrogen bond in 4SCC enabled the formation of an extended, structured hydrogen-bonding network involving water molecules [22]. This rigid network required substantial energy to reorganize during electron transfer, creating a large kinetic barrier. Crucially, when this specific hydrogen bond was disrupted via mutagenesis, the water network was removed, the solvent reorganization energy was reduced, and C-H peroxidation activity was restored [22] [23]. This experiment demonstrates a direct, causal relationship between a defined outer-sphere interaction, solvent reorganization energy, and catalytic function.

Tunable Graphene Electrodes

Recent research has challenged the traditional paradigm that solvent reorganization energy is solely a property of the electrolyte, independent of the electrode. A 2025 study on interfacial ET used van der Waals heterostructures to electrostatically tune the density of states (DOS) at the Fermi level of monolayer graphene [20]. The kinetics of the outer-sphere [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺ redox couple were measured using scanning electrochemical cell microscopy (SECCM).

The results demonstrated that the reorganization energy (λ) is not constant but depends strongly on the electrode's DOS. At low charge carrier densities (low DOS), the electrode's ability to screen charge is weakened, leading to a larger reorganization energy penalty. The observed variation in ET rates with doping level could not be explained by the traditional Marcus-Hush-Chidsey model, which considers the DOS only as a source of electronic states. Instead, the data revealed that the DOS-dependent reorganization energy was the dominant factor governing the ET rate [20]. This finding redefines the understanding of heterogeneous ET, showing that the electronic structure of the electrode itself plays a central role in determining the solvent reorganization energy.

Classical Self-Exchange Reactions

Classic inorganic complexes in solution provide the foundational examples for outer-sphere ET. The self-exchange reaction between [Co(bipy)₃]²⁺ and [Co(bipy)₃]³⁺ proceeds with a rate constant of 18 M⁻¹s⁻¹ [4]. The change in electron configuration from (t₂g)⁵(eg)² to (t₂g)⁶(eg)⁰ involves a significant structural reorganization—a contribution to the inner-sphere λ—which is partly responsible for its relatively slow rate. However, the reorientation of the solvent shell around the changing charge of the metal center also contributes a substantial solvent reorganization energy. These well-characterized systems serve as benchmarks for identifying outer-sphere mechanisms.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Determining Reorganization Energy in Artificial Metalloenzymes

The study on artificial copper proteins employed a multi-faceted approach to determine reorganization energies and correlate them with structure and function [22] [23].

Protein Design and Synthesis:

- Objective: To create self-assembled helical bundles with defined Cu coordination geometries.

- Protocol: The primary sequence was designed using a heptad repeat pattern (

abcdefg)ₙ. Control over oligomeric state (trimer vs. tetramer) was achieved by placing specific hydrophobic residues (Ile for 3SCC, Leu for 4SCC) at theaanddpositions of the heptad to guide "knobs-into-holes" packing. A His residue was introduced at a defined position to serve as the metal ligand [22] [23]. Peptides were synthesized via solid-phase methods.

Structural Characterization:

- Technique: X-ray Crystallography.

- Protocol: Cu-bound 4SCC was crystallized, and its structure was solved to a high resolution (1.36 Å). This confirmed the tetrameric assembly, the Cu(His)₄(OH₂) coordination sphere, and, critically, the presence of the specific His---Glu hydrogen bond and the extended water network [22].

Electronic Structure Analysis:

- Techniques: Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR).

- Protocol: The d-d transition band in the electronic spectrum (~600 nm for 4SCC) provided information on the coordination geometry. The EPR spectrum (axial with gz = 2.253 and Az = 543 MHz for 4SCC) confirmed a type-2 Cu center and allowed quantification of superhyperfine coupling to the nitrogen atoms of the His ligands [22].

Kinetics and Reactivity Assays:

- Protocol: The reduction and reoxidation kinetics of the Cu sites were probed by stopped-flow methods monitored by UV-Vis and EPR spectroscopy. Catalytic activity for C-H peroxidation was assessed by reacting the Cu(I) proteins with H₂O₂ in the presence of a substrate and quantifying product formation [22] [23].

Electrochemical Analysis:

- Protocol: Cyclic voltammetry was used to study the electrocatalytic C-H oxidation activity. Electron transfer reorganization energies (λ) were determined experimentally, likely from analysis of the electrochemical potential dependence of the ET rates [22].

Measuring Interfacial ET Kinetics on Tunable Electrodes

The protocol for investigating the DOS dependence of reorganization energy is as follows [20]:

Electrode Fabrication:

- Objective: Create graphene electrodes with tunable charge carrier density without introducing chemical disorder.

- Protocol: Van der Waals heterostructures are assembled by mechanically stacking monolayer graphene (MLG) onto a dopant layer (e.g., RuCl₃ for hole-doping). The DOS is tuned by inserting hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) spacers of varying thickness (3 nm to 120 nm) between the MLG and the dopant.

Electrochemical Measurement via SECCM:

- Objective: Probe ET kinetics locally at the basal plane of the graphene electrode.

- Protocol: A quartz nanopipette (600–800 nm diameter) is filled with an electrolyte containing the redox probe (2 mM [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺) and supporting electrolyte (100 mM KCl). The nanopipette is brought into contact with the graphene surface, forming a confined meniscus-cell. Cyclic voltammetry is performed within this nanoscale cell.

Data Analysis:

- Objective: Extract the standard ET rate constant (k⁰) and relate it to the electrode DOS.

- Protocol: The half-wave potential (E₁/₂) and shape of the steady-state voltammogram are analyzed to determine k⁰. The variation of k⁰ with the charge carrier density (and thus DOS) of graphene is measured. This data is then fit to a continuum model that incorporates both the number of electronic states and, crucially, the DOS-dependent reorganization energy [20].

The experimental workflow for this approach is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions and Materials for Outer-Sphere ET Research

| Item | Function / Role in Research | Example from Featured Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Designed Peptide Sequences | Forms the scaffold for constructing artificial metalloenzymes with controlled oligomeric state and metal coordination geometry. | (IAAIKQE)ₙ for 3SCC; (LAAIKQE)ₙ for 4SCC [22] [23]. |

| Redox-Active Metal Salts | Serves as the central metal ion in the artificial active site, enabling electron transfer and catalysis. | Copper salts (e.g., CuCl₂) for forming ArCuPs [22]. |

| Outer-Sphere Redox Probes | A molecular couple that undergoes electron transfer without forming chemical bonds with the electrode, used to probe interfacial ET kinetics. | Hexaammineruthenium(III) chloride ([Ru(NH₃)₆]Cl₃) [20]. |

| Van der Waals Heterostructure Components | Used to fabricate model electrodes with tunable electronic properties. | Monolayer Graphene (MLG), hexagonal Boron Nitride (hBN), RuCl₃ dopant layers [20]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Conducts current in electrochemical experiments while minimizing ohmic drop and migration effects. | Potassium Chloride (KCl) [20]. |

| Crystallization Reagents | Used to grow high-quality crystals of artificial proteins for atomic-level structural determination via X-ray diffraction. | Various precipitants, buffers, and salts [22]. |

The comparative analysis of these diverse systems unequivocally demonstrates that solvent reorganization energy is a controllable variable that can dictate the functional outcome of outer-sphere electron transfer. The experimental data shows that:

- In biological and bio-inspired systems, the protein matrix can be engineered to either minimize λ for efficient ET or maximize λ as a regulatory mechanism, as seen in the 3SCC/4SCC comparison [22] [23].

- In electrochemical systems, the traditional view of solvent λ as a property solely of the electrolyte is incomplete; the electronic structure of the electrode is a dominant factor [20].

For researchers validating inner-sphere versus outer-sphere mechanisms, these findings provide a clear roadmap. Key evidence for an outer-sphere pathway includes a significant solvent contribution to the total λ, a rate constant sensitive to solvent properties and outer-sphere interactions, and the absence of a bridging ligand. The methodologies detailed here—from de novo protein design to nanoscale electrochemistry on tunable electrodes—provide a powerful toolkit for systematically probing and controlling this fundamental parameter to guide the design of more efficient catalysts, electronic devices, and biomimetic systems.

Analytical and Computational Strategies for Discriminating ET Pathways

A central challenge in chemistry and electrocatalysis is validating whether a reaction proceeds via an inner-sphere (IS) or outer-sphere (OS) electron transfer (ET) mechanism [24]. In OS-ET, electrons transfer between chemical species without shared ligands or a bridging atom, while IS-ET requires the formation of a chemical bridge or adsorption onto a surface, allowing for direct orbital overlap [17]. Computational tools like Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Molecular Dynamics (MD) are indispensable for distinguishing these pathways at an atomic level, providing insights that are often difficult to obtain experimentally [25] [26]. This guide compares the performance of specific computational methodologies in validating these distinct ET mechanisms, providing researchers with structured data and protocols for their investigative work.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods

Different computational methods offer a balance between computational cost, accuracy, and the specific ET phenomena they can model effectively. The table below summarizes the core methodologies used in this field.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods for Electron Transfer Studies

| Computational Method | Key Strengths | Limitations / Cost | Primary Application in ET Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constrained DFT (CDFT)/MM [26] | Quantifies kinetics for diabatic states; explicitly includes solvent dynamics. | High computational cost; requires specialized expertise. | OS-ET kinetics; distinguishing adiabatic vs. non-adiabatic pathways. |

| Molecular DFT (MDFT) [27] [28] | High numerical efficiency; retains molecular nature of solvent; good for free energy calculations. | Less common in standard software packages. | Calculating reorganization free energies and reaction free energies for ET in solution. |

| CDFT-MD [17] | Accurately parameterizes Marcus theory; models charge-localized diabatic states. | Computationally intensive; definition of diabatic states relies on chemical intuition. | OS-ET pathway analysis and kinetics. |

| Slow-Growth DFT-MD (SG-DFT-MD) [17] | Explores IS-ET pathways with traditional geometric reaction coordinates. | Limited to adiabatic transitions. | IS-ET reaction rates and pathways, particularly with adsorbed intermediates. |

| Machine Learning Emulation of DFT [29] | Orders of magnitude speedup while maintaining chemical accuracy; linear scaling with system size. | Requires extensive training datasets; transferability to new systems can be a challenge. | High-throughput screening of ET properties; large-scale system calculations. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for CDFT/MM Study of SET-Initiated Reactions

This protocol is designed to study Single-Electron Transfer (SET)-initiated reactions, such as those involving organic electron donors like tetrathiafulvalene (TTF), in a solvent environment [26].

System Preparation & Force Field Parameterization:

- Prepare initial structures of the donor and acceptor molecules.

- Obtain molecular mechanics (MM) parameters from force fields like CGenFF or derive them from unrestricted HF/6-31G* calculations if not available [26].

- Solvate the system in a solvent cube (e.g., 40.0 Å for DMF or water) using tools like Packmol or CHARMM-GUI. Remove any solvent molecules within 2.8 Å of the solute's heavy atoms [26].

System Equilibration via Molecular Dynamics:

- Perform a multi-step equilibration using MD software like CHARMM/OpenMM [26]:

- Minimization: 5000 steps using the steepest descent algorithm.

- Heating: From 10 K to 298 K over 5 ps.

- Equilibration: At 298 K for 20-50 ps.

- Apply necessary constraints (e.g., a weak distance constraint between reacting atoms to maintain orientation).

- Perform a multi-step equilibration using MD software like CHARMM/OpenMM [26]:

QM/MM Region Selection and Setup:

- From the equilibrated system, prune the environment to include all molecules within a specific radius (e.g., 12-18 Å) of the QM region.

- Freeze atoms beyond a smaller radius (e.g., 7-10 Å) from the QM region to reduce computational cost [26].

- Define the QM region as the electron donor and acceptor molecules.

Free Energy Surface Calculation:

- Conduct additional MD sampling (e.g., 100 ps) for both the ground and the charge-transferred (SET) electronic states [26].

- For numerous snapshots from this trajectory, perform CDFT/MM energy minimizations for both electronic states using a functional like B3LYP and a 6-31G* basis set.

- Calculate the vertical energy gap (ΔE = ESET - Eground) for each snapshot [26].

Data Analysis via Marcus Theory:

- Assuming Gaussian distributions for ΔE, construct parabolic free energy curves for the reactant and product states.

- Calculate the reorganization energy (λ), reaction free energy (ΔG0), and the activation barrier for ET (ΔG‡) using Marcus theory equations [26]:

- λ = (〈ΔE〉ground - 〈ΔE〉SET)/2

- ΔG0 = (〈ΔE〉ground + 〈ΔE〉SET)/2

- ΔG‡ = (λ + ΔG0)2 / 4λ

Protocol for Distinguishing IS-ET vs. OS-ET in Electrocatalysis

This methodology, applied to studies like CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR), uses different techniques to explicitly compare the two pathways [17].

Modeling the Electrode-Electrolyte Interface:

- Construct a model of the electrocatalyst surface (e.g., Au(110)) in contact with an aqueous electrolyte containing dissolved CO2 and relevant cations (e.g., K+, Li+).

- Use a sufficiently high interfacial cation concentration (e.g., ~2.3 M) to model accumulation effects under reaction conditions [17].

Simulating the OS-ET Pathway with cDFT-MD:

- Use the cDFT method to create diabatic, charge-localized states representing the initial (CO2) and final (CO2δ−(sol)) states of an electron transfer occurring in the solution [17].

- Run cDFT-MD simulations to sample the reorganization energy and electronic coupling for this OS process.

- Parameterize Marcus theory to calculate the kinetic barrier for the OS-ET pathway.

Simulating the IS-ET Pathway with SG-DFT-MD:

- For the IS-ET pathway, where CO2 adsorbs and is reduced on the surface (forming CO2δ−(ads)), use a geometric reaction coordinate, such as the distance between the carbon atom of CO2 and the electrode surface [17].

- Employ an enhanced sampling method like Slow-Growth DFT-MD (SG-DFT-MD) to compute the free energy barrier along this coordinate within the adiabatic framework [17].

Pathway Validation and Analysis:

- Compare the computed free energy barriers for the OS-ET and IS-ET pathways.

- A reaction is validated to proceed via the IS-ET pathway if its barrier is significantly lower than the OS-ET barrier in the presence of cations, as was the case for CO2RR with K+ (IS-ET barrier: 0.61 eV vs. OS-ET barrier: 2.93 eV) [17].

- Analyze the coordination environment (e.g., CO2δ−–K+ ionic bonding) to confirm the short-range interactions that stabilize the IS-ET transition state [17].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting a computational method based on the research objective.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

In computational chemistry, the "research reagents" are the software tools, force fields, and basis sets that enable the simulations.

Table 2: Essential Computational Reagents for ET Studies

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in ET Research | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP [30] | DFT Software | Industry-standard for solid-state/periodic system calculations on surfaces and electrodes. | Paid |

| Gaussian [30] | DFT Software | Industry-standard for high-precision calculations on molecular systems. | Paid |

| ORCA [30] | DFT Software | Strong capabilities for calculating optical properties and high-precision molecular calculations. | Paid (Academic Free) |

| Quantum Espresso [30] | DFT Software | Free software for solid-state/periodic system calculations. | Free |

| CHARMM/OpenMM [26] | Molecular Dynamics | Software for MD simulations for system equilibration and sampling solvent dynamics. | - |

| CGenFF [26] | Force Field | Provides molecular mechanics parameters for organic molecules for MD simulations. | - |

| B3LYP/6-31G* [26] | Functional/Basis Set | A common and reliable combination for QM and QM/MM calculations of organic molecules. | - |

| p4v / VESTA [30] | Visualization | Viewers for visualizing atomic structures, electron densities, and molecular orbitals from calculations. | Free |

Atom Transfer Radical Addition (ATRA) is a cornerstone transformation in synthetic chemistry, enabling the atom-economic difunctionalization of alkenes to access a rich chemical space from simple starting materials [31]. While precious metals like ruthenium and iridium have historically dominated photoredox catalysis, copper-based catalysts have emerged as powerful and sustainable alternatives. Copper offers advantages including earth-abundance, cost-effectiveness, and unique reactivity profiles [32] [33]. However, a fundamental question in copper photoredox chemistry concerns the precise electron transfer mechanism: does catalysis proceed through inner-sphere electron transfer (ISET), where the substrate coordinates directly to the copper center, or outer-sphere electron transfer (OSET), where electron transfer occurs without direct coordination? Resolving these competing pathways is critical for rational catalyst design and reaction optimization.

This case study examines a comprehensive investigation that reconciled experimentally observed outcomes in copper-catalyzed ATRA reactions through an integrated computational and experimental approach [34]. By systematically analyzing the reaction pathways for five sterically and electronically varied alkenes, this research provides a consistent conceptual framework for understanding how catalyst regeneration occurs and ultimately controls reaction outcomes.

Competing Pathways in Copper Photoredox Catalysis

Fundamental Electron Transfer Mechanisms

In copper photoredox catalysis, two primary electron transfer pathways can operate:

- Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer (ISET): Involves direct coordination of the substrate to the copper catalyst's inner coordination sphere, forming a transient bond before electron transfer occurs [34].

- Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer (OSET): Electron transfer proceeds without direct coordination, typically through space or solvent-mediated interactions while the substrate remains outside the catalyst's primary coordination sphere [24].

The distinction between these pathways has profound implications for reaction kinetics, selectivity, and catalyst design. For copper complexes, which undergo facile ligand exchange, ISET pathways often provide unique opportunities for transformations utilizing their inner coordination sphere [31].

Case Study: [Cu(dap)₂]⁺-Mediated ATRA of Olefins and CF₃SO₂Cl

A 2025 integrated computational and experimental study comprehensively examined the viability of competing ISET and OSET processes in [Cu(dap)₂]⁺-mediated ATRA reactions that yield both R−SO₂Cl and R−Cl products [34]. The research selected five representative alkenes with varying steric and electronic properties to explore a range of experimentally observed outcomes.

Table 1: Key Experimental Observations in ATRA Reactions

| Observation | Implication for Mechanism |

|---|---|

| R−SO₂Cl/R−Cl product ratios vary with alkene structure | Product distribution depends on substrate properties |

| Catalyst regeneration is efficiency-dependent on ligands | Supports ISET pathway for catalyst turnover |

| Reaction proceeds with high selectivity for specific alkenes | Consistent with coordination-dependent pathway |

The findings demonstrated that photoexcited [Cu(dap)₂]⁺ initiates photoelectron transfer via ISET, with subsequent regeneration of the oxidized catalyst also occurring through ISET in the ground state to close the catalytic cycle and liberate products [34]. The critical discovery was that R−SO₂Cl/R−Cl product ratios are primarily governed by the relative rates of two key processes:

- Direct catalyst regeneration (i.e., [Cu(dap)₂SO₂Cl]⁺ + R⋅)

- Ligand exchange (i.e., [Cu(dap)₂SO₂Cl]⁺ + Cl⁻)

This mechanistic understanding provides a more consistent and complete framework for understanding how catalyst regeneration occurs and ultimately controls enantioselectivity in ATRA reactions employing chiral copper photocatalysts.

Experimental Analysis and Data Comparison

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The investigation of competing pathways employed multiple complementary techniques:

Computational Methods: Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were utilized to analyze the reaction mechanism of ATRA reactions between perfluoroalkyl iodides and styrene using Cu(I) photoredox catalysts [35]. Calculations assessed the relative energies of proposed intermediates and transition states along competing pathways.

Synthetic Characterization: Structural characterization of copper complexes was performed using NMR, FT-IR, elemental analysis, and X-ray diffraction analysis [32]. Photophysical properties were assessed using UV-Vis spectroscopy and spectrofluorometric measurements in dichloromethane solution and solid state.

Electrochemical Analysis: Cyclic voltammetry measurements determined redox potentials under controlled conditions. For reversible or quasi-reversible redox events, mid-point potentials (E₁/₂) were calculated using: E₁/₂ = (Eₚ,𝒸 + Eₚ,ₐ)/2, where Eₚ,𝒸 and Eₚ,ₐ correspond to cathodic and anodic peak potentials, respectively [24].

Comparative Performance Data

Recent studies with newly developed copper(I) complexes provide quantitative data for comparing catalytic performance:

Table 2: Photophysical Properties and Catalytic Performance of Copper(I) Complexes

| Complex | Absorption Max (nm) | Emission Max (nm) | Excited State Lifetime | ATRA Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Cu(dap)₂]Cl | 437 [31] | Not specified | 270 ns (CH₂Cl₂) [31] | High (various substrates) [34] |

| C1–C5 (dpa derivatives) | Not specified | Visible spectrum [32] | μs regime (CH₂Cl₂) [32] | Remarkable (styrene) [32] |

| Heteroleptic Cu(I) with S-BINAP | Near-UV-visible [32] | Broad visible [32] | Microseconds [32] | High chlorosulfonylation and bromonitromethylation [32] |

Table 3: Comparison of Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Pathways

| Parameter | Inner-Sphere Pathway | Outer-Sphere Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Access | Requires coordination to metal center | No coordination needed |

| Impact of Ligands | Critical - direct involvement | Moderate - primarily electronic effects |

| Solvent Dependence | Lower | Higher - solvent reorganization energy critical [22] |

| Structural Requirements | Specific geometry for coordination | Less restrictive |

| Typical Copper Complexes | [Cu(dap)₂]⁺, heteroleptic Cu(I) with labile ligands | More rigid, saturated coordination spheres |

Visualization of Reaction Pathways

Copper Photoredox ATRA Catalytic Cycle

Competing ISET vs OSET Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Copper Photoredox ATRA Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Copper(I) Complexes | Photoredox Catalyst | [Cu(dap)₂]Cl, [Cu(N,N)(S-BINAP)]⁺ with dpa ligands [32] [31] |

| Dipyridylamine Ligands | N,N-Chelating Ligands | Dpa derivatives with –OMe or –CF₃ substituents [32] |

| Phosphine Ligands | P,P-Auxiliary Ligands | S-BINAP [32] |

| Alkene Substrates | Reaction Substrates | Styrene and derivatives [32] [34] |

| Halogen Sources | Radical Initiators | CF₃SO₂Cl, perfluoroalkyl iodides [34] [35] |

| Solvents | Reaction Medium | Dichloromethane, MeCN [32] [24] |

| Characterization Tools | Analysis | NMR, UV-Vis, cyclic voltammetry, X-ray diffraction [32] |

This case study demonstrates that inner-sphere electron transfer pathways dominate in copper photoredox-catalyzed ATRA reactions, with photoexcited [Cu(dap)₂]⁺ initiating photoelectron transfer via ISET and subsequent catalyst regeneration also occurring through ground-state ISET [34]. The competing ISET/OSET pathways are reconciled through the understanding that product ratios are controlled by relative rates of direct catalyst regeneration versus ligand exchange processes.

The validation of ISET as the predominant pathway provides a more consistent conceptual framework for understanding copper photoredox catalysis. This insight enables rational design of chiral copper photocatalysts for enantioselective ATRA reactions, as the ground-state ISET process that closes the catalytic cycle ultimately controls stereoselectivity. These findings represent a significant advancement in harnessing the unique reactivity of earth-abundant copper catalysts for sustainable synthetic methodologies.

The electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO₂RR) presents a promising pathway for converting a potent greenhouse gas into valuable chemicals and fuels, thereby contributing to a circular carbon economy. While catalyst design has been a primary research focus, the critical influence of the electrolyte environment, particularly cations, on both activity and selectivity has become increasingly apparent. Cation effects have been shown to substantially influence CO₂RR reaction rates and product distribution—it has even been demonstrated that the CO₂RR cannot proceed without cations [17]. The precise mechanisms through which cations exert their influence remain a subject of active debate and investigation, primarily centered on whether their action occurs through inner-sphere or outer-sphere electron transfer pathways [17]. Understanding this distinction is crucial for rationally designing electrochemical systems for CO₂ conversion. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these mechanisms, supported by experimental and computational data, to equip researchers with the knowledge to select and optimize cation environments for specific CO₂RR applications.

Cation Effects: Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer Pathways

At the heart of the mechanistic debate is the mode of electron transfer from the electrode to the CO₂ molecule, a process fundamentally influenced by the presence and identity of cations.

Fundamental Mechanisms

- Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer (OS-ET): In this pathway, the electron is transferred between chemical species that remain separate and intact before, during, and after the event. No chemical bonds are formed or broken in the process, and the electron must move through space from the redox center to the CO₂ molecule [1] [4]. The reaction rate is often described by Marcus Theory, which considers the thermodynamic driving force and the reorganizational energy required for the transfer [1] [4].

- Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer (IS-ET): This mechanism involves electron transfer via a bridging ligand, which in the context of CO₂RR, can be the cation itself. The participating redox sites become connected by a chemical bridge, which typically leads to bond formation and breaking [1]. This pathway allows for more direct interaction and can significantly alter reaction kinetics and pathways.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Inner-Sphere and Outer-Sphere Mechanisms in CO₂RR.

| Feature | Inner-Sphere (IS-ET) | Outer-Sphere (OS-ET) |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction Type | Short-range chemical (coordinative) bonding [17] | Long-range electrostatic interactions [17] |

| Cation Role | Acts as a bridge, directly stabilizing intermediates [17] | Modifies the interfacial electric field [36] |

| Key Intermediate | Adsorbed CO(_2^{\delta -}) (ads) [17] | Solvated CO(_2^-) (sol) [17] |

| Bond Formation | Involves breaking/forming of bonds [1] | No bonds broken or formed [1] |

| Cation Specificity | High (depends on ionic size/charge) [17] | Lower (depends on hydrated size) [36] |

Visualizing the Electron Transfer Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the distinct roles cations play in facilitating CO₂ activation through inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer pathways.

Comparative Experimental Data and Kinetic Barriers

Computational studies using advanced methods like constrained Density Functional Theory Molecular Dynamics (cDFT-MD) have been instrumental in quantifying the effect of cations on the kinetic barriers of the initial CO₂ activation step.

Kinetic Barriers for CO₂ Activation Pathways

The data summarized in the table below demonstrates the profound and cation-specific promotion of the inner-sphere pathway.

Table 2: Computed Kinetic Barriers for the Initial CO₂ Activation Step on a Gold Electrode [17].

| System Environment | OS-ET Barrier (eV) | IS-ET Barrier (eV) | Preferred Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cation-Free (Pure Water) | 1.21 | Not Feasible | Outer-Sphere |

| With K⁺ | 2.93 | 0.61 | Inner-Sphere |

| With Li⁺ | 4.15 | 0.91 | Inner-Sphere |

The data reveals a critical insight: in the absence of cations, only the OS-ET pathway is feasible, albeit with a relatively high barrier. The presence of alkali cations like K⁺ and Li⁺ dramatically inhibits the OS-ET pathway while simultaneously promoting the IS-ET pathway, making inner-sphere the dominant mechanism. The higher barrier for Li⁺ compared to K⁺ in the IS-ET pathway also highlights cation specificity, likely due to differences in hydration structure and binding energy [17].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

To experimentally probe these cation effects, a specific set of reagents and materials is required. The following toolkit outlines the essential components for designing such studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Probing Cation Effects in CO₂RR.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Alkali Metal Salts | Source of cations (Li⁺, Na⁺, K⁺, Cs⁺) to study specificity; the anion is typically bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) or perchlorate (ClO₄⁻) to avoid interference [37] [36]. | KHCO₃, NaClO₄, CsHCO₃ |

| Metal Electrocatalysts | Electrode materials with defined binding strength for CO₂RR intermediates; Au and Ag for CO, Cu for hydrocarbons [17]. | Polycrystalline Au, Ag, Cu; single crystals (e.g., Au(110)) |

| pH Buffers | Control the local proton concentration, which competes with CO₂ reduction and influences product selectivity [38]. | Potassium Phosphate, HCO₃⁻/CO₃²⁻ |

| Computational Models | To simulate interfacial electric fields and cation-intermediate interactions via methods like cDFT-MD and SG-DFT-MD [39] [17]. | cDFT-MD, SG-DFT-MD, Poisson-Boltzmann models |

Core Experimental & Computational Methodologies

Validating the operative electron transfer mechanism requires a combination of advanced experimental and computational techniques.

Key Methodological Approaches

Constrained DFT Molecular Dynamics (cDFT-MD):

- Purpose: To parametrize Marcus Theory and simulate the kinetics of outer-sphere electron transfer (OS-ET) by creating diabatic, charge-localized states [17].

- Protocol: The reaction is simulated along a reorganization coordinate, capturing the effect of solvent and cation reorganization on the electron transfer barrier. This method is crucial for calculating the high barriers associated with OS-ET in the presence of cations [17].

Slow-Growth DFT-MD (SG-DFT-MD):

- Purpose: To explore the reaction kinetics of inner-sphere electron transfer (IS-ET) using geometry-based enhanced sampling within adiabatic transition state theory [17].

- Protocol: This method allows for the direct calculation of the reaction pathway and energy barrier for the formation of adsorbed CO(_2^{\delta -}) intermediate, explicitly accounting for the short-range coordinative interaction with a (partially) desolvated cation [17].

In Situ Vibrational Spectroscopy:

- Purpose: To detect and identify reaction intermediates, such as the critically stabilized CO(_2^{\delta -}) species, and probe the interfacial water structure which is altered by cations [39] [36].

- Protocol: Surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy (SEIRAS) or Raman spectroscopy are used under operational reaction conditions to provide direct evidence of cation-stabilized intermediates and their bonding environment.

Microkinetic Modeling with Electric Field Effects:

- Purpose: To quantitatively deconvolute the effects of cation-induced electric fields from specific adsorption phenomena and predict activity trends across different pH conditions [38] [36].

- Protocol: This involves integrating Poisson-Boltzmann theory to model the interfacial field with ab initio calculations of field effects on reaction intermediates, enabling unprecedented quantitative agreement with experimental activity trends [36].

The interrogation of cation effects reveals a complex interplay at the electrode-electrolyte interface that steers the CO₂RR pathway. The prevailing evidence indicates that inner-sphere electron transfer, facilitated by short-range cation-intermediate interactions, is the dominant promotion mechanism for the critical initial activation of CO₂ on many catalysts [17]. While outer-sphere pathways can operate in pure water, they are effectively suppressed in cation-containing electrolytes relevant to practical applications. The specificity of different cations (e.g., K⁺ vs. Li⁺) arises from their unique abilities to form coordinative bonds and stabilize key intermediates, going beyond simple electrostatic field effects [17] [36]. For researchers designing CO₂RR systems, this implies that selecting the cation is as crucial as selecting the catalyst material itself, as it directly controls the operative reaction mechanism and, consequently, the efficiency and selectivity of CO₂ conversion.

Advanced Modeling with Path Integral Molecular Dynamics for OSET Kinetics

The precise distinction between inner-sphere (IS) and outer-sphere (OS) electron transfer mechanisms represents a fundamental challenge in physical chemistry and biochemistry, with significant implications for catalyst design, enzymatic function, and energy storage systems. Outer-sphere electron transfer (OSET) occurs without significant chemical bond rearrangement between reactants, where electrons tunnel through the outer coordination spheres, while inner-sphere mechanisms involve direct orbital overlap and chemical bridge formation. Path Integral Molecular Dynamics has emerged as a powerful computational framework for capturing nuclear quantum effects that dominate ET processes, providing unprecedented insights into the validation of OSET mechanisms. This review objectively compares the performance of advanced PIMD methodologies against alternative computational approaches, with supporting experimental data, to establish a rigorous validation framework for distinguishing electron transfer mechanisms in complex chemical and biological systems.

The theoretical foundation for this analysis rests on the discretized Feynman path integral formulation, which establishes an isomorphism between quantum particles and classical ring polymers. This approach enables the accurate incorporation of nuclear quantum effects—including zero-point energy, quantum delocalization, and tunneling—into molecular dynamics simulations of electron transfer kinetics. As demonstrated in recent experimental studies of artificial copper proteins, the reorganization energy (λ), particularly the outer-sphere solvent contribution, serves as a critical experimental observable for validating computational predictions of OSET mechanisms.

Computational Methodologies for Electron Transfer Kinetics

Path Integral Molecular Dynamics Frameworks

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced PIMD Methodologies for OSET Kinetics

| Method | Computational Approach | Quantum Effects Captured | System Size Limit | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEP-PIMD [40] | Neuroevolution potentials with PIMD integration | NQEs, isotope effects, thermal properties | Large-scale (1000+ atoms) | High efficiency with near-DFT accuracy |

| TRPMD [40] | Thermostatted ring-polymer MD | Quantum vibrations, zero-point energy, tunneling | Medium-scale (100-500 atoms) | Improved thermal sampling and dynamics |

| PI-FEP/UM [41] | Path integral-free energy perturbation/umbrella sampling | Kinetic isotope effects, tunneling, quantized vibrations | Small-medium scale (50-200 atoms) | Excellent for KIE calculations and reaction rates |

| QM/MM-PI [41] | Combined quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical path integrals | Electronic structure, NQEs, solvent effects | Small-scale (10-100 QM atoms) | Accurate treatment of bond breaking/formation |

| Mean-Field PIMD [42] | Path integrals for fermions with reduced complexity | Electron correlation, fermion sign problem | Medium-scale (electron systems) | Addresses fermion sign problem (O(n³) scaling) |