From Theory to Bedside: Mastering the Nernst Equation for Advanced Potentiometric Analysis in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Nernst equation as the fundamental principle underpinning modern potentiometry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

From Theory to Bedside: Mastering the Nernst Equation for Advanced Potentiometric Analysis in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Nernst equation as the fundamental principle underpinning modern potentiometry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It bridges core theoretical concepts with practical applications, detailing how electrode potential measurements enable precise quantification of ionic species and biomarkers critical to pharmaceutical and clinical studies. The scope extends from foundational electrochemistry and sensor design to advanced methodological applications in complex biological matrices, systematic troubleshooting of analytical performance, and rigorous validation against established techniques. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge innovations in miniaturization and point-of-care diagnostics, this resource serves as a complete guide for developing, optimizing, and validating robust potentiometric methods in biomedical research.

The Electrochemical Bridge: Core Principles of the Nernst Equation in Potentiometry

This whitepaper delineates the fundamental principles of the Nernst equation, establishing its critical role as the quantitative bridge between the measured electrode potential in an electrochemical cell and the activity of ions in solution. As the cornerstone of potentiometric techniques, the Nernst equation provides the theoretical foundation for determining ion concentrations, calculating equilibrium constants, and predicting the spontaneity of redox reactions under non-standard conditions. Framed within ongoing potentiometry research, this guide details the equation's derivation, its precise mathematical formulations, and its indispensable applications in scientific and industrial domains, particularly pharmaceutical development. The document is supplemented with structured data presentations, detailed experimental protocols, and visualizations to serve as a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists.

Electrochemical processes are fundamental to a vast array of modern technologies, from energy storage systems to analytical sensors. At the heart of quantifying these processes lies the Nernst equation, introduced by the German chemist Walther Hermann Nernst in 1887 [1]. This equation is one of the two central equations in electrochemistry [2]. It precisely describes the dependency of an electrode's potential on its immediate chemical environment [2]. In essence, the Nernst Equation tells us what the potential of an electrode is when the electrode is surrounded by a solution containing a redox-active species with an activity of its oxidized and reduced species [2].

Within the context of potentiometry research, which measures the voltage of an electrochemical cell to determine the concentration of ions in a solution, the Nernst equation is the fundamental law that connects the measured signal (potential) to the desired analyte (ion activity) [3]. This technique is vital for its simplicity, speed, and minimal sample preparation, making it invaluable in fields like drug development for monitoring electrolyte levels and ensuring product quality [3]. The equation's power lies in its ability to extend predictions from standard, idealized conditions to the real-world, non-standard conditions—variable concentrations, temperatures, and pressures—encountered in laboratory and industrial settings.

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

Thermodynamic Derivation

The Nernst equation is derived from the principles of chemical thermodynamics, particularly the relationship between Gibbs free energy and electrochemical work. The maximum useful electrical work that can be obtained from an electrochemical cell is given by ( \Delta G = -nFE ), where ( n ) is the number of electrons transferred, ( F ) is the Faraday constant, and ( E ) is the cell potential [4] [5]. Under standard conditions, this becomes ( \Delta G^o = -nFE^o ).

For a reaction proceeding under any set of conditions, the change in Gibbs free energy is related to the standard change and the reaction quotient, ( Q ), by: [ \Delta G = \Delta G^o + RT \ln Q \label{1} \tag{1} ]

Substituting the electrochemical work terms yields: [ -nFE = -nFE^o + RT \ln Q \label{2} \tag{2} ]

Dividing through by ( -nF ) provides the most general form of the Nernst equation: [ E = E^o - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q \label{3} \tag{3} ]

Where:

- ( E ) is the cell potential under non-standard conditions.

- ( E^o ) is the standard cell potential.

- ( R ) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K).

- ( T ) is the temperature in Kelvin.

- ( n ) is the number of moles of electrons transferred in the redox reaction.

- ( F ) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C/mol).

- ( Q ) is the reaction quotient.

For a general redox reaction: [ aA + bB \rightarrow cC + dD ] the reaction quotient ( Q ) is expressed in terms of the activities of the species: [ Q = \frac{{aC}^c \cdot {aD}^d}{{aA}^a \cdot {aB}^b} ] For practical purposes, and in dilute solutions, concentrations can often be used in place of activities [6].

Mathematical Forms at Various Conditions

The following table summarizes the key forms of the Nernst equation for different experimental scenarios.

Table 1: Forms of the Nernst Equation for Different Conditions

| Application | Mathematical Form | Key Variables |

|---|---|---|

| General Form | ( E = E^o - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q ) | Applicable at all temperatures [6]. |

| At 298 K (25°C) | ( E = E^o - \frac{0.0592}{n} \log_{10} Q ) | Uses base-10 logarithm for convenience [4] [6] [5]. |

| Single Electrode Potential (for ( M^{n+} + ne^- \rightarrow M )) | ( E = E^o - \frac{0.0592}{n} \log_{10} \frac{1}{[M^{n+}]} ) | Relates reduction potential to ion concentration; activity of solid metal ( M ) is 1 [5]. |

| Cell Potential | ( E{cell} = E^o{cell} - \frac{0.0592}{n} \log_{10} Q ) | Used to calculate the potential of a full electrochemical cell [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Core Components for Potentiometric Research

A robust potentiometry setup relies on specific reagents and materials to ensure accurate and reproducible measurements.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl, Calomel) | Provides a stable, known potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured, crucial for all potentiometric measurements [3]. |

| Indicator Electrode (e.g., Ion-Selective Electrode - ISE) | The sensing element whose potential changes in response to the activity of a specific ion in the test solution, as described by the Nernst equation [3]. |

| Standard Solutions | Solutions of known, precise concentration used to calibrate the electrode system and generate a calibration curve, which is vital for determining unknown concentrations [3]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | A high-strength ionic solution added to both standards and samples to maintain a constant ionic background, minimizing the junction potential and ensuring the activity coefficient is constant [3]. |

| Faraday Constant (F) | A fundamental physical constant (96,485 C/mol) representing the charge of one mole of electrons, central to the calculation in the Nernst equation [4] [5]. |

The Nernst Equation in Potentiometry and Research Applications

Core Principle of Potentiometric Measurement

Potentiometry is an electrochemical technique that measures the voltage (potential) of an electrochemical cell under conditions of zero current [3]. This measurement is performed between a reference electrode, which maintains a constant potential, and an indicator electrode, which develops a potential that depends on the activity of the target ion [3]. The Nernst equation is the fundamental principle that describes the response of the indicator electrode. For an ion-selective electrode (ISE) for a cation ( M^{n+} ), the potential is given by: [ E = E^o + \frac{2.303RT}{nF} \log_{10} [M^{n+}] ] This linear relationship between the measured potential and the logarithm of the ion concentration allows for the direct determination of unknown concentrations through a calibration curve [3].

Key Research Applications

The Nernst equation enables a wide range of critical applications in research and analysis:

Determination of Equilibrium Constants: At equilibrium, the cell potential ( E{cell} = 0 ) and the reaction quotient ( Q ) equals the equilibrium constant ( K ). The Nernst equation simplifies to: [ E^o{cell} = \frac{0.0592}{n} \log{10} K \label{4} \tag{4} ] This allows for the highly accurate determination of solubility constants (( K{sp} )), formation constants, and other thermodynamic equilibrium constants [4] [5].

pH Measurement: The glass pH electrode is a classic example of a potentiometric sensor whose operation is governed by the Nernst equation. For the hydrogen ion, the equation becomes ( E = E^o - 0.0592 \, \text{pH} ) at 25°C, providing a direct link between measured potential and pH [3].

Clinical and Pharmaceutical Analysis: Ion-selective electrodes are used to measure critical electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and chloride in biological fluids such as blood and urine [3]. This is essential for disease diagnosis and monitoring drug effects.

Environmental Monitoring: Potentiometric sensors are deployed to measure ions like nitrate and fluoride in water sources, providing vital data for environmental and public health protection [3].

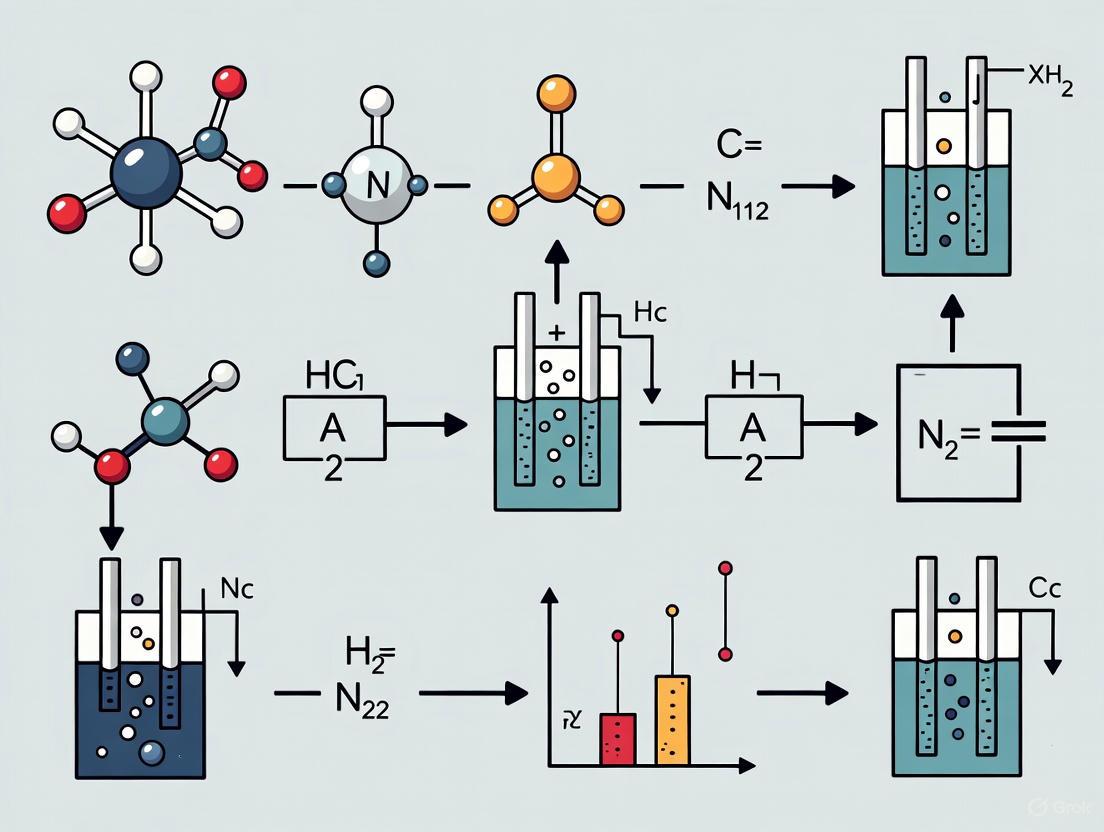

The logical workflow for applying the Nernst equation in analytical research, from fundamental principles to final application, is visualized below.

Diagram 1: Nernst Equation Application Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol A: Determination of an Unknown Ion Concentration

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for using an Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) to determine the concentration of an ion in a solution, a common practice in pharmaceutical quality control labs.

Principle: The potential of the ISE is measured versus a reference electrode in standard solutions of known concentration. A calibration curve of potential vs. log(concentration) is plotted, which should be linear as per the Nernst equation. The potential of an unknown sample is then measured and its concentration is determined from the calibration curve.

Materials:

- Ion-selective electrode for target ion (e.g., Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺)

- Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl with double junction)

- Potentiometer (high-impedance voltmeter) or pH/mV meter

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars

- Volumetric flasks, beakers, pipettes

- Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) specific to the analyte ion

- Standard stock solution of the analyte ion (e.g., 1000 ppm)

- Deionized water

- Unknown sample solution

Procedure:

- Calibration Curve Preparation: a. Prepare a series of standard solutions by diluting the stock solution (e.g., 10⁻¹ M, 10⁻² M, 10⁻³ M, 10⁻⁴ M). b. Add an equal volume of ISA to each standard solution and to the unknown sample to maintain constant ionic strength. c. Immerse the ISE and reference electrode in the most dilute standard. d. Under gentle stirring, record the stable potential reading in millivolts (mV). e. Rinse the electrodes with deionized water and blot dry. f. Repeat steps c-e for each standard solution in order of increasing concentration.

- Sample Measurement: a. Immerse the electrodes in the prepared unknown sample. b. Under gentle stirring, record the stable potential reading in mV. c. Rinse the electrodes thoroughly with deionized water after measurement.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the measured potential (mV) on the Y-axis against the logarithm of the concentration (log[C]) of the standard solutions on the X-axis.

- Perform a linear regression to obtain the equation of the best-fit line (Y = slope * X + intercept). The slope should be close to the theoretical Nernstian slope (e.g., ~59.2/n mV/decade at 25°C).

- Substitute the measured potential of the unknown sample (Y) into the linear equation and solve for X (log[C]).

- The antilog of X gives the concentration of the analyte in the unknown sample.

Protocol B: Calculation of an Equilibrium Constant

This protocol describes the use of the Nernst equation to determine the equilibrium constant (( K_{eq} )) of a redox reaction, which is valuable for characterizing APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) prone to redox degradation.

Principle: A galvanic cell is constructed from the redox reaction of interest. The standard cell potential (( E^o{cell} )) is calculated from standard reduction potentials. The cell potential (( E{cell} )) is measured at known concentrations. The Nernst equation is then used with ( E{cell} = 0 ) at equilibrium to solve for ( K{eq} ).

Materials:

- Electrodes (e.g., Zn rod, Cu rod)

- Salt bridge (e.g., KNO₃ in agar)

- Solutions of known concentration (e.g., 1.0 M ZnSO₄, 0.001 M CuSO₄)

- Voltmeter (potentiometer)

- Beakers, wires

Procedure (Example for Zn | Zn²⁺ || Cu²⁺ | Cu):

- Construct the electrochemical cell: In one beaker place a Zn electrode in 1.0 M ZnSO₄. In a second beaker, place a Cu electrode in 0.001 M CuSO₄. Connect the two half-cells with a salt bridge.

- Connect the Zn electrode (anode) and Cu electrode (cathode) to a voltmeter.

- Measure the initial cell potential (( E_{cell} )).

- Allow the cell to discharge until the potential reaches 0 V (equilibrium). The concentrations at this point can be used to calculate ( K ), though the calculation is more straightforward using the standard potential.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the standard cell potential: ( E^o{cell} = E^o{cathode} - E^o_{anode} ). For Zn/Cu, this is +0.337 V - (-0.763 V) = +1.10 V [4].

- At equilibrium, ( E{cell} = 0 ) and ( Q = K{eq} ). The Nernst equation becomes: [ 0 = E^o{cell} - \frac{0.0592}{n} \log{10} K{eq} ] [ \log{10} K{eq} = \frac{nE^o{cell}}{0.0592} \label{5} \tag{5} ]

- For the Zn/Cu reaction where ( n=2 ) and ( E^o{cell} = +1.10 V ): [ \log{10} K{eq} = \frac{2 \times 1.10}{0.0592} \approx 37.2 ] [ K{eq} = 10^{37.2} \approx 1.6 \times 10^{37} ] This very large value indicates the reaction strongly favors products at equilibrium [4] [1].

The relationship between cell potential and the reaction progress towards equilibrium is conceptualized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: Cell Potential Evolution to Equilibrium

Advanced Concepts and Current Research Frontiers

Three-Dimensional Visualization of Nernstian Behavior

Advanced graphical representations, such as 3-D trend surfaces ("topos"), have been developed to visualize redox equilibria governed by the Nernst equation [7]. These plots map the electrode potential (z-axis) against the activities of both the oxidized and reduced species (x and y-axes). The resulting surfaces characteristically show a steep "cliff" where one species is depleted and a broad "plateau" where the potential is close to the standard potential ( E^0 ) [7]. These visualizations are powerful tools for teaching and for intuitively understanding how potential evolves along a reaction path in a galvanic cell until the cell "dies" when the potentials of the two half-cells equalize [7].

Limitations and Considerations

While powerful, the Nernst equation has limitations that researchers must consider:

- Activity vs. Concentration: The equation is rigorously defined in terms of ion activity, not concentration. In solutions with high ionic strength (>0.001 M), the activity coefficient can deviate significantly from unity, and concentrations must be corrected for accurate results [6] [5].

- Current Flow: The equation assumes equilibrium conditions with zero current flow. When a current flows, effects such as resistive losses and overpotential occur, which the Nernst equation does not account for [5].

- Non-Nernstian Behavior: Some sensor materials may not exhibit the ideal Nernstian slope (59.2/n mV at 25°C), or their response may be affected by interfering ions. Careful characterization is essential.

Future Directions in Potentiometry Research

Current research is pushing the boundaries of Nernstian potentiometry. Key areas include:

- Miniaturization and Solid-State Electrodes: Development of robust, solid-state ion-selective electrodes and miniaturized sensors for point-of-care diagnostics and in-vivo monitoring [3].

- Nanotechnology: Integration of nanomaterials to enhance electrode performance, sensitivity, and detection limits [3].

- Advanced Materials: Exploration of new sensing materials with improved selectivity, longer lifetimes, and reduced susceptibility to biofouling.

- Multiplexed Sensor Arrays: Combining multiple potentiometric sensors into arrays for simultaneous analysis of several ions, creating "electronic tongues" for complex mixture analysis.

The Nernst equation stands as a cornerstone of electrochemistry, providing a critical bridge between the thermodynamic driving force of redox reactions and the practical experimental conditions under which they occur. In the context of potentiometry research, particularly in drug development where precise measurements of ion concentrations and reaction equilibria are paramount, a thorough understanding of this equation is non-negotiable. It elegantly describes the relationship between the electrochemical potential of a cell and the composition of the solution, enabling researchers to predict cell voltages under non-standard conditions and determine critically important equilibrium constants, including solubility constants vital for pharmaceutical solubility studies [4]. This guide deconstructs the equation into its fundamental parameters, providing researchers and scientists with a detailed technical reference for application in advanced potentiometric research.

Fundamental Theory and Derivation

The Nernst Equation is derived from the principles of thermodynamics, linking the measurable cell potential to the Gibbs free energy change of the redox reaction. The derivation begins with the relationship between the Gibbs free energy change under non-standard conditions (ΔG) and the standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°):

[ \Delta G = \Delta G^o + RT \ln Q \label{1} ]

where (Q) is the reaction quotient. The electrical work done by a galvanic cell is given by (-nFE), which, under reversible conditions, equals the change in Gibbs free energy, (\Delta G) [8]. Substituting the Gibbs free energy terms with their electrochemical equivalents ((\Delta G = -nFE) and (\Delta G^o = -nFE^o)) yields:

[ -nFE = -nFE^o + RT \ln Q \label{2} ]

Dividing through by (-nF) provides the most general form of the Nernst Equation:

[ E = E^o - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q \label{3} ]

This form can be adapted for base-10 logarithms, which is more convenient for practical calculations:

[ E = E^o - \frac{2.303 RT}{nF} \log_{10} Q \label{4} ]

At standard temperature (298.15 K or 25 °C), the constants can be consolidated, simplifying the equation for laboratory use [4]:

[ E = E^o - \frac{0.0592\, \text{V}}{n} \log_{10} Q \label{5} ]

This expression is indispensable for predicting cell potentials outside of standard-state conditions, a scenario routinely encountered in experimental research.

Parameter Deconstruction

A deep understanding of each variable in the Nernst Equation is crucial for its correct application in potentiometric experiments. The following table summarizes these core parameters and their physical significance.

Table 1: Core Parameters of the Nernst Equation

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition & Role | Standard Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Potential | (E) | The measured electromotive force (EMF) or voltage of an electrochemical cell under non-standard conditions. It is the primary observable in potentiometric measurements. | Volts (V) |

| Standard Cell Potential | (E^o) | The intrinsic EMF of a cell under standard state conditions (all activities = 1, T = 298.15 K, P = 1 atm). It is a constant for a given redox reaction and indicates thermodynamic spontaneity. | Volts (V) |

| Universal Gas Constant | (R) | A fundamental physical constant that relates energy and temperature scales. It is the proportionality constant in the ideal gas law and thermodynamic equations. | 8.314 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹ |

| Temperature | (T) | The absolute temperature at which the electrochemical reaction occurs. It directly influences the thermal energy available to the system and the value of the pre-logarithmic term. | Kelvin (K) |

| Moles of Electrons | (n) | The number of moles of electrons transferred in the balanced redox reaction. It quantifies the stoichiometry of the electron transfer process. | Dimensionless (mol) |

| Faraday's Constant | (F) | The magnitude of electric charge per mole of electrons. It converts between chemical moles of electrons and electrical charge. | 96,485 C·mol⁻¹ |

| Reaction Quotient | (Q) | The ratio of the activities (approximated by concentrations) of the reaction products to reactants, each raised to the power of its stoichiometric coefficient. It describes the instantaneous composition of the system. | Dimensionless |

In-Depth Parameter Analysis

The Potential Terms ((E) and (E^o)): While (E^o) is a fixed property of a reaction, obtained from reference tables, the measured potential (E) is a dynamic variable. It reflects the system's departure from standard conditions as dictated by the reaction quotient (Q) and temperature (T). A positive (E) indicates a spontaneous reaction, while a negative (E) signifies non-spontaneity [4]. In potentiometry, (E) is the direct signal from which analyte concentration is derived.

The Constants ((R) and (F)): (R) and (F) are fundamental constants. Their combination in the term (RT/nF) has units of volts and represents the thermal voltage, scaling the logarithmic term's influence on the cell potential. At room temperature, (2.303RT/F \approx 0.0592\, V) [4] [9].

The Stoichiometric and Compositional Terms ((n) and (Q)): The value of (n) must be determined from a fully balanced redox reaction. An error in (n) propagates directly into the calculated potential. The reaction quotient (Q) for a general reaction (aA + bB \rightarrow cC + dD) is (Q = \frac{{aC}^c \cdot {aD}^d}{{aA}^a \cdot {aB}^b}). For dissolved species, activities are approximated by molar concentrations; for gases, by partial pressures; and for pure solids or liquids, their activity is 1 [9].

Experimental Methodology in Potentiometry

The practical application of the Nernst equation in research, such as determining equilibrium constants or quantifying analyte concentrations, requires rigorous experimental protocols.

Protocol: Determination of an Equilibrium Constant via Cell Potential Measurement

1. Principle: The equilibrium constant (K) for a redox reaction can be determined electrochemically by measuring the standard cell potential (E^o) and using the relationship derived from the Nernst equation at equilibrium, where (E = 0) and (Q = K) [4]: [ 0 = E^o - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln K \quad \Rightarrow \quad \log K = \frac{nE^o}{0.0592\, \text{V}} \quad (\text{at } 298 \text{ K}) ]

2. Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | A precision instrument for applying potential and accurately measuring the resulting cell voltage with high impedance to minimize current draw. |

| Electrochemical Cell | A multi-port vessel (e.g., H-cell) to house the working, reference, and counter electrodes and the analyte solution. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential (e.g., Saturated Calomel Electrode, Ag/AgCl). The Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) defines the zero point [10]. |

| Working Electrode | The electrode at which the reaction of interest occurs (e.g., Pt, Au, Glassy Carbon). Material is selected for inertness and relevant electrochemical window. |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the circuit, often made of inert platinum wire. |

| High-Purity Salts & Solvents | To prepare analyte solutions with precisely known concentrations. |

| Salt Bridge | An ionic connection (e.g., KCl-agar) between half-cells to complete the circuit while preventing solution mixing [2]. |

3. Procedure: a. Cell Assembly: Construct a galvanic cell where the reaction of interest is the cell reaction. For example, to find (K) for (Zn{(s)} + Cu^{2+}{(aq)} \rightleftharpoons Zn^{2+}{(aq)} + Cu{(s)}), a Zn electrode in a Zn²⁺ solution and a Cu electrode in a Cu²⁺ solution are connected via a salt bridge [4]. b. Potential Measurement: Using a high-impedance voltmeter, measure the cell potential (E) at a controlled temperature of 25 °C. Ensure reactants and products are at standard concentrations (1 M for solutions, 1 atm for gases). c. Data Analysis: Under these standard conditions, the measured potential (E) is equal to (E^o). Use the simplified relationship (\log K = \frac{nE^o}{0.0592}) to calculate the equilibrium constant.

Workflow and Parameter Relationships

The following diagram visualizes the logical workflow for a potentiometric experiment and the interplay of Nernst equation parameters, from experimental setup to final result.

Diagram 1: Potentiometric Experiment Workflow

Advanced Considerations

Activity vs. Concentration

The thermodynamically correct form of the Nernst equation uses the chemical activities (a) of the species involved, not their concentrations. Activity accounts for non-ideal behavior in solutions, especially at medium and high concentrations where electrical interactions between ions become significant. The activity of a dissolved species i is defined as (ai = γi Ci), where (γi) is its activity coefficient and (Ci) is its molar concentration [9]. For dilute solutions ((< 0.001 M)), (γi ≈ 1), and concentrations can be used directly. In more concentrated pharmaceutical solutions, this approximation breaks down, and activity coefficients must be considered for high-precision work.

The Formal Potential ((E^{o'}))

To simplify work with real-world solutions where activity coefficients are unknown or difficult to determine, electrochemists use the formal potential ((E^{o'})), also called the conditional potential [9]. It is defined as:

[ E^{o'} = E^{o} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln\left(\frac{\gamma{\text{Red}}}{\gamma{\text{Ox}}}\right) ]

This incorporates the activity coefficients into the standard potential, yielding a modified Nernst equation:

[ E = E^{o'} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln\left(\frac{C{\text{Red}}}{C{\text{Ox}}}\right) ]

The formal potential is the experimentally observed potential when the concentrations of the oxidized and reduced species are equal ((C{Red}/C{Ox} = 1)) and all other solution conditions (ionic strength, pH, presence of complexing agents) are specified. It is highly dependent on the medium and is more practical for analytical applications than the standard potential [9].

Parameter Interrelationships

The following diagram maps the complex dependencies and relationships between the core parameters of the Nernst equation, illustrating how they collectively determine the cell's behavior.

Diagram 2: Nernst Equation Parameter Relationships

A meticulous, parameter-level understanding of the Nernst equation transcends academic exercise and is a fundamental prerequisite for robust potentiometric research in fields like drug development. The deconstruction of (E), (E^o), (R), (T), (n), (F), and (Q) reveals the elegant synergy between thermodynamics and experimental electrochemistry. Mastering these parameters, along with advanced concepts like formal potential and activity, empowers scientists to design more precise experiments, from determining critical equilibrium constants for drug solubility to developing novel electrochemical sensors. This detailed guide serves as a technical foundation upon which researchers can build to advance their potentiometric analyses and contribute to the broader field of analytical chemistry.

In potentiometry and the study of electrochemical cells, the Nernst equation provides the fundamental link between the measured potential of an electrochemical cell and the activities (often approximated by concentrations) of the ionic species involved [4] [9]. For researchers and scientists in drug development, this relationship is the cornerstone of a wide array of analytical techniques, from ion-selective electrode measurements to the assessment of membrane potentials in physiological studies. The equation quantitatively describes the equilibrium potential established across a membrane or at an electrode interface when a specific ion is permeable. A key feature of this relationship is its predictable, temperature-dependent slope, with a characteristic value of 59.16 mV per decade change in concentration for a monovalent ion (z = 1) at 25°C [11] [12]. This value, universally known as the "Nernstian slope," serves as a critical benchmark for validating experimental systems, designing sensors, and interpreting biological signals. This guide delves into the origin, interpretation, and practical application of this ideal slope, with a focused comparison between monovalent and divalent ions, framed within the context of rigorous potentiometric research.

Theoretical Foundation of the Nernstian Slope

Derivation from Basic Principles

The Nernst equation is derived from the principles of thermodynamics, relating the electrical work of an electrochemical cell to the chemical free energy change of the underlying redox reaction [4] [8]. For a general reduction half-reaction: [ \ce{Ox + ze^{-} <=> Red} ] the Nernst equation for the half-cell potential is expressed as: [ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}} ] where:

- (E) is the equilibrium potential (Volts, V)

- (E^0) is the standard electrode potential (V)

- (R) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹) [11]

- (T) is the absolute temperature (Kelvin, K)

- (z) is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction (the charge of the ion for simple metal/metal-ion electrodes)

- (F) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹) [11]

- (a{\text{Red}}) and (a{\text{Ox}}) are the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively

For a metal ion in solution ((M^{z+})) in equilibrium with its pure metal, the reduced form is the solid metal, which has an activity of 1. Assuming the activity of the oxidized form ((M^{z+})) can be approximated by its concentration ([(M^{z+})]), the equation simplifies to [13]: [ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{1}{[M^{z+}]} = E^0 + \frac{RT}{zF} \ln [M^{z+}] ]

The Origin of the 59.16 mV Value

The factor ( \frac{RT}{F} ) is a fundamental constant in electrochemistry, representing the "thermal voltage." At standard temperature (25°C or 298.15 K), its value is: [ \frac{RT}{F} = \frac{(8.314 \, \text{J·mol}^{-1}\text{·K}^{-1}) \times (298.15 \, \text{K})}{96,485 \, \text{C·mol}^{-1}} \approx 0.02569 \, \text{V} = 25.69 \, \text{mV} ] Most practical measurements use base-10 logarithms (log) rather than natural logarithms (ln). The conversion is given by ( \ln(x) = 2.303 \log(x) ). Substituting this into the Nernst equation gives: [ E = E^0 + \frac{2.303 RT}{zF} \log [M^{z+}] ] The pre-logarithmic term ( \frac{2.303 RT}{F} ) at 25°C is: [ \frac{2.303 RT}{F} = 2.303 \times 0.02569 \, \text{V} \approx 0.05916 \, \text{V} = 59.16 \, \text{mV} ] Thus, the final, widely-used form of the Nernst equation for a cation (M^{z+}) at 25°C becomes: [ E = E^0 + \frac{0.05916}{z} \log [M^{z+}] ] This equation reveals that the measured potential changes by ( \frac{59.16}{z} ) millivolts for every tenfold change in the ion concentration [4] [12]. The slope of a plot of (E) versus (\log [M^{z+}]) is therefore ( \frac{59.16}{z} ) mV/decade.

The Critical Role of Ion Valency (z)

The valency of the ion (z) is the decisive factor in the slope of the Nernstian response, as it is inversely proportional to the term (59.16/z).

For Monovalent Ions (

z = 1) such as K⁺, Na⁺, Li⁺, H⁺, and Cl⁻, the ideal Nernstian slope is: ( \frac{59.16}{1} = 59.16 \, \text{mV/decade} ) This means a tenfold increase in the concentration of a monovalent cation will cause the equilibrium potential to increase by 59.16 mV.For Divalent Ions (

z = 2) such as Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, and Zn²⁺, the ideal slope is: ( \frac{59.16}{2} = 29.58 \, \text{mV/decade} ) The higher charge means the electrical driving force is twice as effective per decade of concentration change, resulting in a slope that is exactly half of that for a monovalent ion [11].

The table below summarizes the ideal Nernstian slopes for different ion types at 25°C.

Table 1: Ideal Nernstian Slopes for Different Ion Valencies at 25°C

Ion Valency (z) |

Example Ions | Ideal Nernstian Slope (mV per decade) |

|---|---|---|

| +1 (Monovalent Cations) | K⁺, Na⁺, H⁺, NH₄⁺ | +59.16 |

| -1 (Monovalent Anions) | Cl⁻, I⁻, NO₃⁻ | -59.16 |

| +2 (Divalent Cations) | Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Cu²⁺, Zn²⁺ | +29.58 |

| -2 (Divalent Anions) | SO₄²⁻, CO₃²⁻ | -29.58 |

The following diagram illustrates the logical and mathematical relationships that lead to the ideal Nernstian slope.

Diagram 1: Derivation Path of the Nernstian Slope. This flowchart outlines the logical sequence from fundamental thermodynamics to the practical equation used to calculate the ideal Nernstian slope.

Experimental Protocols for Slope Validation

Validating that an electrochemical system (e.g., an ion-selective electrode) exhibits the ideal Nernstian slope is a critical step in confirming its proper function and measurement accuracy.

Calibration of an Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE)

Objective: To determine the response slope of an Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) for a target ion and verify its conformity to the ideal Nernstian slope.

Materials and Reagents:

- Ion-Selective Electrode: Specific to the ion of interest (e.g., Ca²⁺-ISE).

- Reference Electrode: Double-junction or single-junction (e.g., Ag/AgCl).

- Potentiometer/Millivoltmeter: High-impedance voltmeter capable of measuring mV with 0.1 mV resolution.

- Standard Solutions: A series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target ion, covering a range of at least 3 decades (e.g., 10⁻⁵ M, 10⁻⁴ M, 10⁻³ M, 10⁻² M, 10⁻¹ M).

- Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA): A high-strength salt solution (e.g., KNO₃ or NaCl) added to all standards and samples to maintain a constant and high ionic background. This minimizes the variation in the activity coefficient, ensuring that concentration can be used in place of activity [12].

Procedure:

- Setup: Connect the ISE and reference electrode to the potentiometer. Immerse the electrodes in a beaker containing a low-ionic-strength rinse solution (e.g., deionized water).

- Conditioning: If required by the manufacturer, condition the ISE by soaking it in a solution of the target ion (e.g., 10⁻³ M) for 30 minutes prior to the first use.

- Measurement: a. Start with the most dilute standard solution. Add the prescribed volume of ISA to the standard and stir gently and consistently. b. Thoroughly rinse the electrodes with deionized water and blot dry with a laboratory wipe. c. Immerse the electrodes in the standard solution, allow the potential reading to stabilize (typically 1-2 minutes), and record the millivolt value. d. Repeat steps 3a-3c for all standard solutions in order of increasing concentration.

- Data Analysis:

a. Plot the recorded potential (mV, y-axis) against the logarithm (base 10) of the ion concentration (x-axis).

b. Perform a linear regression analysis on the data points to obtain the equation of the best-fit line (y = mx + b, where m is the slope).

c. Compare the experimentally determined slope (

m) to the ideal Nernstian slope (59.16/zmV). A slope within ±5% of the ideal value is often considered indicative of a well-functioning electrode.

Measurement of Membrane Equilibrium Potentials in Physiology

Objective: To demonstrate the Nernst potential across a biological or artificial membrane permeable to a specific ion.

Background: In physiology, the Nernst equation calculates the equilibrium potential for an ion across a semi-permeable membrane. This potential is a result of the concentration gradient of the permeant ion. Researchers often simulate this using artificial lipid bilayers or cultured cells.

Materials and Reagents:

- Recording Setup: Voltage-clamp or current-clamp amplifier.

- Microelectrodes: Fine-tipped glass microelectrodes (for intracellular recording) or patch-clamp pipettes.

- Cell or Vesicle Preparation: A single cell (e.g., neuron, oocyte) or an artificial lipid vesicle.

- Bath and Pipette Solutions: Solutions with precisely defined concentrations of the ion of interest (e.g., K⁺). A classic experiment involves varying extracellular K⁺ concentration ([K⁺]ₒ) while measuring membrane potential.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a set of extracellular solutions where the concentration of K⁺ is varied (e.g., 1 mM, 3 mM, 10 mM, 30 mM, 100 mM), while maintaining osmolarity and the concentrations of other ions.

- Impaling the Cell: Using a micromanipulator, carefully impale a single cell with the microelectrode to measure its intracellular potential relative to the bath ground.

- Perfusion and Recording: a. Continuously perfuse the cell with the control (low K⁺) solution. Record the resting membrane potential. b. Switch the perfusion to a solution with a higher known [K⁺]ₒ. c. Allow the membrane potential to stabilize and record the new value. d. Repeat for all K⁺ solutions.

- Data Analysis: a. Plot the measured membrane potential (mV, y-axis) against log₁₀([K⁺]ₒ) (x-axis). b. Fit a linear regression to the data. The slope of this line should approach the ideal Nernst slope for K⁺ (-59.16 mV/decade at 25°C, negative as the potential becomes more positive with higher external K⁺). Deviations indicate that the membrane is not exclusively permeable to K⁺, which is often the case in real cells.

The workflow for a typical calibration experiment is summarized below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Validating Nernstian Slope. This chart outlines the standard operational procedure for calibrating an ion-selective electrode to validate its Nernstian response.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation with the Nernst equation requires precise materials and an understanding of their function.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Solutions | A series of solutions with known, precise concentrations of the analyte ion. Serve as the calibration curve for potential vs. log(concentration). | 10⁻⁵ M to 10⁻¹ M KCl solutions for calibrating a K⁺-ISE. |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | A high-concentration inert electrolyte added to all standards and samples. Swamps out the variable sample background, making the activity coefficient constant. This allows concentration to be used directly in the Nernst equation [12]. | 4 M KNO₃ for Ca²⁺ or K⁺ measurements. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, fixed reference potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured. Critical for a stable mV reading. | Ag/AgCl electrode with KCl filling solution. |

| High-Impedance Potentiometer | Measures voltage without drawing significant current. Prevents polarization of the electrodes and ensures an accurate reading of the equilibrium potential. | pH/mV meter with >10¹² Ω input impedance. |

| Formal Potential (E⁰') | The measured standard potential under a defined set of solution conditions (e.g., specific ionic strength). It is used in place of the thermodynamic E⁰ when concentrations are used instead of activities for more accurate practical calculations [9] [12]. | The y-intercept of the calibration curve is the formal potential. |

Advanced Considerations and Non-Ideal Behavior

While the ideal slope is a crucial benchmark, several factors can cause experimental results to deviate.

Temperature Dependence

The Nernst slope is directly proportional to the absolute temperature T [11]. For experiments conducted at temperatures other than 25°C, the slope must be recalculated using the formula (2.303RT)/F. For example, at physiological temperature (37°C or 310.15 K), the ideal slope for a monovalent ion is approximately 61.54 mV/decade.

Activity vs. Concentration

The Nernst equation is rigorously defined in terms of ion activity, not concentration. Activity (a) is related to concentration (C) by the activity coefficient (γ): a = γC. In dilute solutions, γ≈1, but in concentrated or complex matrices (e.g., biological fluids), γ can be significantly less than 1. The use of an ISA is the primary methodological approach to mitigate this issue [9] [12].

Non-Nernstian Response and its Implications

A measured slope significantly lower than the ideal value (e.g., 50 mV/decade for a monovalent ion) indicates a non-ideal response. This can be caused by:

- Electrode Drift or Aging: A degraded or fouled ion-selective membrane.

- Insufficient Selectivity: Interference from other ions in the solution.

- Incorrect Ionic Strength: Leading to variable activity coefficients.

- Junction Potentials: Unstable liquid junction potentials in the reference electrode. Identifying and troubleshooting the cause of a sub-Nernstian response is essential for obtaining reliable potentiometric data.

The Nernstian slope of 59.16/z mV is not merely a theoretical constant but a practical gold standard in potentiometric research. Its derivation from first principles provides a solid thermodynamic foundation, while its dependence on ion valency offers a clear, quantifiable prediction for system behavior. For researchers in drug development and the broader life sciences, a deep understanding of this relationship is indispensable. It enables the calibration of critical analytical tools like ion-selective electrodes, informs the interpretation of electrophysiological data, and provides a rigorous framework for assessing the performance of novel sensor technologies. Mastery of the concepts and experimental protocols surrounding the Nernstian slope ensures that scientific conclusions drawn from potentiometric measurements are both accurate and reliable.

In potentiometry, the fundamental relationship between the measured potential of an electrochemical cell and the analyte of interest is governed by the Nernst equation. This equation, in its fundamental form, describes the potential as a function of the logarithm of ion activity, not concentration [14] [9]. For an ion with charge ( z ), the electrode potential is given by: [ E{\mathrm{cell}} = K + \frac{0.05916}{z} \log(aA) ] where ( E{\mathrm{cell}} ) is the cell potential, ( K ) is a constant, and ( aA ) is the activity of the ion A [14]. The distinction between activity and concentration is therefore not merely academic; it is foundational to interpreting potentiometric signals accurately, especially in complex matrices like pharmaceutical formulations or biological fluids.

Activity can be defined as the effective concentration of an ion in a solution, accounting for its interactions with all other species in the solution [15]. It is related to the measured concentration ( [M^{n+}] ) by the activity coefficient ( \gamma{M^{n+}} ): [ a{M^{n+}} = [M^{n+}] \gamma_{M^{n+}} ] The activity coefficient, and thus the activity, is influenced by the ionic strength of the solution, a function of the concentrations and charges of all ions present [14] [15]. In ideal, infinitely dilute solutions, inter-ionic interactions are negligible, ( \gamma \approx 1 ), and activity equals concentration. However, in the real-world solutions analyzed by researchers and development professionals, this is rarely the case.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Activity and Concentration

| Feature | Activity | Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Effective, thermodynamically active concentration | Analytical amount per unit volume |

| Governing Factor | Ion activity coefficient (( \gamma )) and concentration | Preparation and dilution |

| Dependence | Ionic strength and solution matrix | Independent of solution matrix |

| Nernst Equation | Directly related to potential | Related only if ( \gamma \approx 1 ) |

| Practical Use | Measures free, bioavailable ions | Measures total content |

The Nernst Equation: Bridging Theory and Practice

The Central Role in Potentiometry

The Nernst equation is the cornerstone of potentiometric analysis, providing the mathematical link between an electrochemical potential and the composition of a solution [4] [2]. For a half-cell reduction reaction of the form [ \text{Ox} + ze^- \longrightarrow \text{Red} ] the Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E = E^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}} ] where ( E ) is the half-cell potential, ( E^{\ominus} ) is the standard electrode potential, ( R ) is the universal gas constant, ( T ) is the absolute temperature, ( F ) is the Faraday constant, and ( a{\text{Red}} ) and ( a{\text{Ox}} ) are the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [9] [4]. At room temperature (25 °C), this equation simplifies using the thermal voltage approximation, and for a metal/metal ion electrode, it reduces to the form shown in Section 1 [9] [4].

From Activity to Concentration in Practice

To make potentiometry a practical tool for determining concentration, the Nernst equation must be reconciled with the activity-concentration relationship [14]. Substituting ( a{M^{n+}} = [M^{n+}] \gamma{M^{n+}} ) into the Nernst equation yields: [ E{\mathrm{cell}} = K + \frac{0.05916}{n} \log \gamma{M^{n+}} + \frac{0.05916}{n} \log [M^{n+}] ] The first two terms on the right are often combined into a new constant, ( K' ), simplifying the equation to: [ E{\mathrm{cell}} = K' + \frac{0.05916}{n} \log [M^{n+}] ] This simplification is only valid if the activity coefficient is constant [14]. This is a critical consideration for experimental design: by ensuring that the standards and samples have an identical, or very similar, ionic matrix, the value of ( \gamma{M^{n+}} ) remains fixed, and the measured potential becomes a direct function of the logarithm of the concentration [14]. This is the principle upon which most quantitative potentiometric methods are built.

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from a sample to a concentration measurement, highlighting the central role of the Nernst equation and the activity-concentration relationship.

Diagram 1: From Sample to Concentration in Potentiometry

Experimental Protocols: Navigating the Distinction

Calibration and Matrix-Matching Protocol

The primary methodology for ensuring that potentiometric measurements accurately reflect concentration is through careful calibration with matrix-matched standards [14].

Objective: To construct a calibration curve that relates the measured cell potential to the analyte concentration, thereby accounting for the constant activity coefficient. Procedure:

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Prepare a series of standard solutions of the analyte with known concentrations that bracket the expected concentration in the sample.

- Matrix Matching: Add an inert electrolyte (e.g., KNO₃, NaCl) to each standard solution to adjust the ionic strength to a high and constant value. The chosen ionic strength should approximate or exceed that of the sample solutions. This swamps out variations in ionic strength between standards and samples, ensuring a constant activity coefficient [14] [15].

- Potential Measurement: Measure the cell potential for each standard solution using the appropriate ion-selective electrode and reference electrode.

- Calibration Curve: Plot the measured potential (E) versus the logarithm of the known concentration (log [Mⁿ⁺]). The slope of the linear region should be close to the Nernstian value (59.16/z mV at 25 °C).

- Sample Measurement: Measure the potential of the sample solution, which must contain the same inert electrolyte at the same concentration as the standards. Determine the unknown concentration from the calibration curve.

Determination of Free vs. Total Concentration

Potentiometry uniquely measures the activity of the free, uncomplexed ion, which is a key advantage in speciation and bioavailability studies [14] [16]. This protocol can be used to investigate metal ion speciation.

Objective: To determine the concentration of free metal ions in a solution containing complexing agents. Procedure:

- Total Concentration: Determine the total metal ion concentration (e.g., using atomic absorption spectroscopy) on an aliquot of the sample.

- Free Concentration: Measure the potential of the sample directly using a calibrated ion-selective electrode for the metal ion. The measured potential corresponds to the activity of the free metal ion. Using the calibration curve, this activity is converted to the free metal concentration, acknowledging that the activity coefficient is accounted for in the calibration [14] [16].

- Data Analysis: The difference between the total concentration and the free concentration represents the complexed fraction of the metal ion. This is crucial in pharmaceutical development for understanding drug-protein binding or the speciation of active ingredients.

Table 2: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Trace Metal Analysis

| Technique | Measured Quantity | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiometry | Activity of free ion | Direct information on bioavailability/speciation | Requires careful control of ionic strength |

| Voltammetry | Concentration of electrochemically labile species | High sensitivity | Complexed or inert species not detected |

| Atomic Spectrometry | Total elemental concentration | Insensitive to chemical form | No information on speciation or bioavailability |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of potentiometric methods relies on a set of key reagents and materials designed to manage the activity-concentration relationship and ensure measurement integrity.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Potentiometry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | Swamps out variable ionic strength in samples and standards, ensuring a constant activity coefficient for accurate concentration measurements [14]. | Typically a high concentration of an inert electrolyte (e.g., 1 M KNO₃). Must not contain ions that interfere with the electrode. |

| Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) | The indicator electrode whose potential is selectively sensitive to the activity of a specific ion in solution [17]. | Selectivity varies; check selectivity coefficients for expected interferents. Requires proper storage and conditioning. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, constant potential against which the ISE potential is measured [18] [17]. | Ag/AgCl or saturated calomel electrodes (SCE) are common. Requires periodic refilling with correct filling solution. |

| Standard Solutions | Used to construct the calibration curve that relates measured potential to analyte concentration [14]. | Must be prepared with high-purity materials and matrix-matched with the ISA to the samples. |

| Liquid Junction / Salt Bridge | Completes the electrical circuit between the ISE and reference electrode while minimizing liquid junction potential [18]. | Often an integral part of the reference electrode. Uses an electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃) that does not cause precipitation. |

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

The distinction between activity and concentration, when properly navigated, opens doors to powerful analytical applications. In environmental chemistry, potentiometric sensors with sub-nanomolar detection limits are used to measure free copper ions in seawater, providing critical data on metal bioavailability and toxicity that total concentration measurements cannot offer [16]. In clinical chemistry, ion-selective electrodes measure electrolytes like Na⁺ and K⁺ in blood serum. The reported value is a concentration, but this is only valid because the measurement system is calibrated with standards that mimic the serum matrix, effectively controlling for activity coefficients [17].

In pharmaceutical research, this principle is applied to study the binding of drug candidates to proteins or other macromolecules. By using a potentiometric sensor to monitor the free drug ion concentration before and after adding the binding partner, the binding constant can be determined, as the electrode only responds to the free, unbound ion [16]. The following workflow visualizes a typical experiment for studying ion speciation or binding using potentiometry.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Speciation/Binding Analysis

Navigating the distinction between activity and concentration is not a theoretical obstacle but a practical necessity in potentiometric research. A deep understanding of the Nernst equation reveals that the electrode signal is fundamentally tied to ion activity. Through rigorous experimental protocols—primarily the use of ionic strength adjustment and matrix-matched calibration—researchers can transform this activity-based signal into an accurate and reliable measure of concentration. This careful approach enables scientists across pharmaceutical, clinical, and environmental disciplines to leverage the unique advantage of potentiometry: the ability to detect the biologically and chemically active free ion, providing insights that are completely lost when only the total concentration is measured.

In potentiometric research, particularly when applying the Nernst equation to complex biological environments, the selection of the correct reference potential is paramount for obtaining accurate, reliable data. The fundamental Nernst equation, E = E⁰ - (RT/nF)ln(Q), relates the measured potential (E) to the reaction quotient (Q), with E⁰ representing the standard reference potential under defined conditions [19] [20]. However, researchers confront a critical decision: whether to use the standard potential (E°), which applies only to ideal standardized conditions, or the formal potential (E°'), which accounts for the real-world complexities of biological matrices. This distinction becomes especially crucial in pharmaceutical and clinical applications where measurements occur in saliva, blood, or other biofluids containing numerous interfering species, variable pH, and complex matrices that significantly alter electrochemical behavior [21] [22].

The formal potential is not merely a theoretical adjustment but a practical necessity for accurate in-situ and point-of-care measurements. It is defined as the potential of a redox couple under a specific set of experimental conditions, including pH, ionic strength, and presence of complexing agents, where the activity coefficients for the oxidized and reduced species are incorporated into the resulting potential E°' [19]. Unlike the standard potential, which is a universal constant tabulated for standard conditions (1 M concentrations, 1 atm pressure for gases, 298.15 K), the formal potential is environment-dependent and must be determined for each experimental setup [19]. This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations, practical implications, and methodological approaches for selecting and applying the correct potential in biologically-relevant potentiometric research, framed within the broader context of Nernst equation application in modern electroanalytical science.

Theoretical Foundations: Standard vs. Formal Potential

Standard Electrode Potential (E°)

The standard electrode potential provides the fundamental reference point for all electrochemical measurements. By definition, E° represents the inherent tendency of a redox species to acquire electrons relative to the Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE), which is assigned a value of 0 V under standard conditions: 298.15 K, 1 atm pressure for gases, and 1 M concentrations for solutes [23] [20]. These idealized conditions establish a reproducible baseline that enables comparison of different redox couples across experimental systems. The SHE consists of a platinum electrode immersed in a 1 M H⁺ solution with hydrogen gas bubbled at 1 atm pressure, creating the reference half-reaction: 2H⁺(aq, 1 M) + 2e⁻ ⇌ H₂(g, 1 atm) [23].

When determining standard potentials for other half-cells, galvanic cells are constructed with the SHE as one electrode and the half-cell of interest as the other. For instance, to establish the standard potential for the Cu²⁺/Cu redox couple, the cell Pt(s) | H₂(g, 1 atm) | H⁺(aq, 1 M) || Cu²⁺(aq, 1 M) | Cu(s) yields a measured potential of +0.337 V, which is assigned as E° for the Cu²⁺/Cu couple [23]. This systematic approach has generated comprehensive tables of standard reduction potentials that serve as starting points for predicting reaction spontaneity and cell potentials under idealized conditions.

Formal Potential (E°')

The formal potential represents a practical correction to the standard potential that accounts for non-ideal experimental conditions. According to PalmSens, a knowledgeable source in electrochemistry, "The two activity coefficients fOx and fRed are included in the resulting potential E⁰', which is called the formal potential" [19]. Since these activity coefficients depend on the chemical environment, the formal potential incorporates the effects of variables such as ionic strength, pH, complexation, and temperature that diverge from standard conditions.

The mathematical relationship between standard and formal potential emerges from the Nernst equation. For a generalized reduction reaction: Ox + ne⁻ → Red, the Nernst equation is:

Where a_Red and a_Ox represent the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively. Substituting activity coefficients (γ) and concentrations (C) (a = γC) yields:

The combination E° - (RT/nF) * ln(γ_Red/γ_Ox) constitutes the formal potential E°', resulting in the practical form of the Nernst equation:

This formulation is particularly valuable in biological systems where activity coefficients deviate significantly from unity due to high ionic strength and specific molecular interactions [19].

Comparative Analysis: Key Distinctions

Table 1: Comparison between Standard Potential and Formal Potential

| Characteristic | Standard Potential (E°) |

Formal Potential (`E°') |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Potential under standard conditions (1 M, 1 atm, 298.15 K) | Potential under specific experimental conditions |

| Reference | Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) | Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) |

| Activity Coefficients | Assumed to be 1 (ideal behavior) | Incorporated into the value |

| Environmental Factors | Ignores pH, ionic strength, complexation | Accounts for pH, ionic strength, complexation |

| Tabulation | Universally tabulated for redox couples | Must be determined for each experimental system |

| Applications | Predicting spontaneity, theoretical calculations | Quantitative analysis in real matrices |

The fundamental distinction lies in their applicability: while E° provides a theoretical benchmark, E°' offers practical utility for quantitative work in complex media. As noted in the research literature, "Since it contains parameters that depend on the environment, such as temperature and activity coefficients, E⁰' cannot be listed but needs to be determined for each experiment, if necessary" [19]. This requirement for experimental determination makes formal potential both context-dependent and mathematically convenient for analytical applications.

The Challenge of Biological Matrices

Biological matrices such as blood, saliva, urine, and cellular lysates present particularly challenging environments for potentiometric measurements due to their complex and variable composition. These systems contain numerous electroactive interferents, proteins, lipids, and electrolytes that can foul electrode surfaces, alter activity coefficients, and participate in secondary reactions [21] [22]. The ISE (ion-selective electrode) design must overcome these challenges to achieve accurate readings in clinical and pharmaceutical contexts.

Saliva, for instance, contains various components including sodium chloride, magnesium bicarbonate, calcium bicarbonate, sodium phosphate, urea, and ammonium oxide, all of which can potentially interfere with measurements of target analytes [22]. Similarly, blood plasma exhibits variable electrolyte balances and contains numerous biomolecules that can adsorb to electrode surfaces. A study of electrolyte disorders found that 15% of hospitalized patients suffer from at least one electrolyte imbalance, with hyponatremia (7.7%) and hypernatremia (3.4%) being most prevalent [21]. Even slight abnormalities in electrolyte balance can significantly affect potential measurements if not properly accounted for in the calibration approach.

The pH variability in biological systems particularly impacts the formal potential of pH-dependent redox couples. A notable example is the NAD⁺/NADH couple, where the standard reduction potential is -0.358 V, but at physiological pH (7.0), the formal potential shifts to approximately -0.56 V due to the involvement of H⁺ in the reduction reaction: NAD⁺ + 2e⁻ + H⁺ → NADH [24]. This substantial difference of over 0.2 volts demonstrates why using standard potentials without adjustment for biological conditions would lead to significant analytical errors.

Table 2: Impact of Biological Matrix Components on Potential Measurements

| Matrix Component | Effect on Potential Measurement | Consequence for E⁰ Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Variable pH | Shifts equilibrium for H⁺-dependent reactions | Requires use of pH-adjusted formal potential |

| High Ionic Strength | Alters activity coefficients (γ ≠ 1) | Formal potential essential for accurate quantification |

| Electroactive Interferents | Compete for electron transfer | Increases importance of selectivity coefficients |

| Macromolecules (proteins, lipids) | Surface fouling, reduced electrode responsiveness | Necessitates frequent calibration or formal potential verification |

| Complexing Agents | Shift effective concentration of free ions | Formal potential incorporates complexation equilibria |

Determining Formal Potential for Biological Applications

Experimental Methodology

The determination of formal potential for a specific biological application requires a systematic experimental approach centered around the Nernst equation. The general methodology involves constructing a calibration curve under conditions that closely mimic the target biological matrix. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for formal potential determination:

Matrix-Matched Standard Preparation: Prepare standard solutions of the target analyte across a concentration range relevant to the biological application (typically 3-5 orders of magnitude). The standard matrix should approximate the ionic strength, pH, and protein content of the target biological fluid using appropriate buffers and additives [22]. For saliva analysis, Britton-Robinson buffer (BRB) adjusted to pH 7 has been effectively employed [22].

Potentiometric Measurement: Immerse the indicator and reference electrodes in each standard solution and measure the equilibrium potential once a stable reading is obtained (typically within 1-2 mV drift per minute). The reference electrode selection should be appropriate for biological measurements, with Ag/AgCl being particularly common due to its stability and biocompatibility [21] [22].

Data Analysis: Plot the measured potential (E) against the logarithm of the analyte concentration (log C). Perform linear regression to determine the slope and intercept of the calibration curve. The formal potential (

E°') corresponds to the potential value when the concentration ratioC_Red/C_Ox = 1(or whenlog C = 0for a single species), which is the y-intercept of the regression line [19].Validation: Confirm the determined formal potential by measuring potentials in spiked biological samples with known analyte additions. The recovery should approach 100% if the formal potential is correctly established for the matrix.

Case Study: NAD⁺/NADH Formal Potential at pH 7

The calculation of formal potential for pH-dependent systems demonstrates the critical adjustment needed for biological applications. For the NAD⁺/NADH couple with the reaction:

NAD⁺ + 2e⁻ + H⁺ → NADH

The Nernst equation is:

E = E° - (RT/2F) * ln([NADH]/([NAD⁺][H⁺]))

Which can be rearranged as:

E = E° - (RT/2F) * ln(1/[H⁺]) - (RT/2F) * ln([NADH]/[NAD⁺])

Recognizing that E°' = E° - (RT/2F) * ln(1/[H⁺]), and substituting [H⁺] = 10^(-7) for pH 7, the formal potential becomes:

E°' = E° - (0.05916/2) * log(1/10^(-7)) at 25°C

E°' = E° - (0.02958) * 7

E°' = -0.358 V - 0.207 V = -0.565 V

This significant shift of -0.207 V from the standard potential of -0.358 V to a formal potential of -0.565 V at physiological pH highlights the essential nature of this adjustment for accurate biological redox measurements [24].

Addressing Matrix Effects in Complex Biofluids

In particularly complex matrices like saliva or blood, additional strategies may be necessary to account for matrix effects:

Standard Addition Method: When the matrix composition is unknown or highly variable, the standard addition method can be employed where small volumes of concentrated standard are added directly to the sample, and the potential change is measured to determine the original concentration without explicit knowledge of the formal potential.

Matrix-Matching: For routine analysis, calibration standards can be prepared in artificial saliva or simulated plasma that approximates the major ionic components of the biological fluid [22].

Internal References: For some applications, incorporating an internal reference redox couple of known formal potential in the specific matrix can provide an in-situ calibration point.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of formal potential measurements in biological matrices requires careful selection of materials and reagents. The following table outlines essential components for such research:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Formal Potential Determination in Biological Matrices

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) | Target analyte recognition | PVC membrane with ionophore, MWCNT-modified for enhanced sensitivity [22] |

| Reference Electrode | Stable potential reference | Double-junction Ag/AgCl electrode (prevents contamination) [22] |

| Buffer Systems | pH control and ionic strength adjustment | Britton-Robinson buffer (pH 2-11 range) [22] |

| Ion-to-Electron Transducers | Signal enhancement in solid-contact ISEs | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), conducting polymers (PEDOT) [21] [22] |

| Matrix Modifiers | Reduction of nonspecific binding | Salt modifications to paper substrates for heavy metal detection [25] |

| Selectivity Enhancers | Minimize interferent effects | Ionophores with high specificity for target ions [21] |

The development of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) with advanced transducing materials represents a significant advancement for biological measurements. As noted in recent research, "Various types of transducers have been used in SC-ISEs based largely on conducting polymers and carbon-based materials" including "polyaniline, poly(3-octylthiophene), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)" as common conducting polymers, while "colloid-imprinted mesoporous carbon, MXenes, multi-walled carbon nanotubes have all been explored as the SC" [21]. These materials improve potential stability and reduce drift in complex biological matrices.

Experimental Workflow for Formal Potential Application

The following diagram illustrates the systematic decision process for selecting and applying the correct potential in biological potentiometric measurements:

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for potential selection

Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

The field of potentiometric sensing in biological matrices continues to evolve with several promising trends enhancing the accuracy and application of formal potential measurements. Recent research has focused on addressing the challenges of point-of-care testing through innovative sensor designs and materials [21] [25].

Emerging Technologies

Wearable potentiometric sensors represent a growing application area where formal potential calibration is essential for accurate continuous monitoring. These devices allow for tracking of electrolytes, biomarkers, and even pharmaceuticals in biological fluids, particularly those with narrow therapeutic indices [21]. The development of 3D-printed electrodes offers improved flexibility and precision in manufacturing ion-selective electrodes, enabling rapid prototyping and optimization of electrochemical parameters [21]. Similarly, paper-based sensors provide cost-effective, versatile platforms for in-field point-of-care analysis, permitting rapid determination of various analytes in biological samples [21].

Nanocomposite materials have shown particular promise for enhancing formal potential stability in biological measurements. Recent research demonstrates that "electron transfer kinetics, sensitivity, selectivity and response times could be improved by combining nanomaterials such as metal nanoparticles, graphene, and carbon nanotubes as the transducer layer" [21]. For example, "tubular gold nanoparticles with Tetrathiafulvalene (Au-TFF) solid contact layer that was used for the determination of potassium ions and showed high capacitance and great stability" [21].

Calibration-Free Approaches

A significant challenge in point-of-care potentiometry is the need for frequent calibration, which has prompted research into calibration-free sensors. These designs aim for high reproducibility in standard potential (E°) from sensor to sensor, allowing a single calibration curve to be used for an entire batch of sensors [25]. As noted in recent literature, "The term 'calibration-free' has been used to refer to sensors with a low batch-to-batch standard deviation in the value of E0" [25]. However, the acceptable level of reproducibility depends on application requirements, particularly for diagnostic tests where clinical decision thresholds dictate tolerable errors.

The distinction between standard potential and formal potential is not merely academic but fundamentally practical for researchers working with biological systems. While standard potential provides a theoretical foundation for understanding redox thermodynamics, formal potential offers the necessary correction for accurate quantitative work in complex matrices like blood, saliva, and cellular environments. The experimental determination of formal potential through matrix-matched calibration represents a critical step in method development for clinical, pharmaceutical, and biological potentiometric applications.

As potentiometric sensors continue to evolve toward miniaturized, wearable, and point-of-care formats, the appropriate selection and application of formal potential will remain essential for translating raw potential measurements into clinically and scientifically meaningful data. By understanding the theoretical basis, methodological approaches, and practical considerations outlined in this technical guide, researchers can more effectively navigate the complexities of electrochemical measurements in biological environments, ultimately leading to more reliable data and robust analytical conclusions.

From Principle to Practice: Implementing Potentiometric Sensors in Biomedical Assays

Potentiometry is a fundamental electrochemical technique for determining the activity of ions in solution by measuring the potential (voltage) difference between two electrodes under conditions of zero current flow [26] [21]. This method relies on the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the electrochemical potential of an electrode and the activity of ionic species in the surrounding solution [12] [2]. For researchers in drug development and analytical sciences, understanding the precise roles and interactions of the three core components—the ion-selective electrode (ISE), the reference electrode, and the high-impedance voltmeter—is crucial for designing accurate and reliable sensing systems, particularly for applications such as therapeutic drug monitoring and physiological ion measurement [27] [21].

The Nernst equation for a general reduction reaction (aA + ne⁻ ⇔ bB) is expressed as:

E = E⁰ - (RT/nF) ln([B]ᵇ/[A]ᵃ)

where E is the electrode potential, E⁰ is the standard electrode potential, R is the universal gas constant, T is temperature in Kelvin, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is the Faraday constant, and [A] and [B] are the activities of the oxidized and reduced species, respectively [12]. At 25°C, this simplifies to E = E⁰ - (0.0592/n) log([B]ᵇ/[A]ᵃ), providing the theoretical foundation for all potentiometric measurements [12].

Core Component 1: The Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE)

The Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) serves as the primary sensing element in the potentiometric cell. Its fundamental purpose is to generate an electrical potential that varies predictably with the activity (effective concentration) of a specific target ion in the sample solution [28] [26]. This potential development occurs across a specialized ion-selective membrane, which is the heart of the ISE [26].

Operational Mechanism

The ISE functions by establishing a phase boundary potential at the interface between its ion-selective membrane and the sample solution [26]. This potential arises from an ion-exchange or ion-transport process that occurs selectively for the target ion [26]. The membrane is designed to be permeable only to the target ion, creating a charge separation across the membrane-solution interface [28]. The resulting electrical potential follows a Nernstian response, meaning it changes by approximately 59.2 mV per tenfold change in ion activity for a monovalent ion at 25°C [28] [12]. The key principle is that the voltage developed across the membrane depends on the logarithm of the specific ionic activity, as predicted by the Nernst equation [28].

Membrane Types and Composition

The selectivity of an ISE is determined almost entirely by the composition of its membrane. Different membrane types have been developed to target specific ions across various application domains [28].

Table 1: Types of Ion-Selective Membranes and Their Characteristics

| Membrane Type | Composition | Target Ions | Selectivity Mechanism | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Membranes | Silicate or chalcogenide glass [28] | H⁺ (pH), Na⁺, Ag⁺, other single-charged cations [28] | Ion-exchange properties of the glass matrix [28] | pH electrodes, sodium analysis in blood/urine [28] |

| Crystalline Membranes | Monocrystalline or polycrystalline salts (e.g., LaF₃ for fluoride) [28] | F⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻, CN⁻, S²⁻, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ [28] | Ions that can integrate into the crystal lattice [28] | Fluoride detection in water, heavy metal monitoring [28] |

| Ion-Exchange Resin Membranes | Polymer membranes (e.g., PVC) with incorporated ionophore [28] [29] | Wide range of single- and multi-atom ions [28] | Selective complexation by the ionophore [28] | Clinical chemistry, environmental analysis [28] [27] |

| Enzyme Electrodes | Enzyme-containing layer over a standard ISE [28] | Substrates like glucose, urea, creatinine [28] | Enzyme reaction produces a detectable ion (e.g., H⁺) [28] | Biomedical sensing, bioreactor monitoring [28] |

For polymer-based membranes, the typical composition includes [29]:

- Polymer Matrix: Usually poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) or similar polymers that provide structural integrity.

- Plasticizer: An organic solvent that gives the membrane the proper flexibility and influences the dielectric constant.

- Ionophore: A selective ion carrier molecule that dictates the electrode's selectivity (e.g., BAPTA for Ca²⁺) [29].

- Ionic Additives: Lipophilic salts added to reduce membrane resistance and optimize potential response.

Core Component 2: The Reference Electrode

The reference electrode provides a stable, constant potential against which the potential of the ISE is measured [30]. Its key characteristic is that its potential remains unaffected by the composition of the sample solution, creating a reproducible reference point for the potentiometric cell [26] [30].

Design and Electrolyte Systems

A reference electrode maintains its stable potential through a redox couple at equilibrium within a fixed-concentration electrolyte solution [30]. The most common systems include:

- Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl): A wire of silver coated with solid silver chloride (AgCl) is immersed in a solution containing chloride ions (typically KCl) [28] [30]. The half-cell reaction is AgCl(s) + e⁻ ⇌ Ag(s) + Cl⁻(aq). This system is non-toxic, has a wide temperature range (up to 140°C), and is widely used in commercial electrodes [30].