Cyclic Voltammetry for Redox Reaction Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for the analysis of redox reactions, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Cyclic Voltammetry for Redox Reaction Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for the analysis of redox reactions, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including the interpretation of voltammograms and key equations like Randles-Sevcik. The guide details methodological setup, from electrode selection to experimental parameters, and highlights diverse applications from neurotransmitter detection to anticancer drug analysis. It further offers practical troubleshooting advice for common experimental issues and explores advanced validation techniques, including the comparison with other analytical methods and the integration of computational models like Density Functional Theory (DFT) for predictive analysis.

Understanding Cyclic Voltammetry: Core Principles and Redox Theory

In the field of electrochemical research, the three-electrode system is a foundational setup for conducting precise and controlled experiments. It has become standard equipment in research laboratories for investigating reaction mechanisms, optimizing battery performance, and developing next-generation energy materials [1]. Unlike the two-terminal batteries used in daily life, the three-electrode system is a specialized laboratory configuration designed for accurate measurement and control [2].

This system's development was a significant advancement over the simpler two-electrode setup. Historically, two-electrode systems were used but had major drawbacks, particularly in measuring and controlling electrode potentials, which led to considerable errors. The introduction of the reference electrode in the 1920s, thereby creating the three-electrode system, greatly improved the precision and reproducibility of electrochemical experiments [2]. The core principle of this system is the separation of current control from potential measurement, enabling independent control of the working electrode potential while the counter electrode carries the system current [2].

The Roles and Requirements of the Three Electrodes

A typical three-electrode electrochemical cell consists of three distinct components: the Working Electrode (WE), the Reference Electrode (RE), and the Counter Electrode (CE), also known as the auxiliary electrode [2] [1]. Each plays a unique and critical role.

Working Electrode (WE)

The Working Electrode is the core of the electrochemical cell, where the reaction of interest occurs [2] [1]. Its properties are critical for obtaining meaningful data.

- Role: The WE is the electrode under study; the electrochemical reaction being investigated happens at its surface [2] [3].

- Requirements: An ideal working electrode should be chemically inert to the electrolyte, have a reproducible and uniform surface, and present a controlled geometric area [2] [1]. Its surface must be free of impurities, which often necessitates pre-treatment steps like polishing and cleaning before experiments [1] [3].

- Common Materials: Glassy carbon, platinum (Pt), gold (Au), silver (Ag), and conductive oxides such as FTO and ITO [2] [1].

Reference Electrode (RE)

The Reference Electrode acts as a stable potential benchmark in the system [1].

- Role: It provides a known, stable reference potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured and controlled [2]. Crucially, it is designed to carry virtually no current, ensuring its potential remains constant [2] [3].

- Requirements: An optimal reference electrode has a well-defined and stable potential, high exchange current density (making it non-polarizable), and does not react with the electrolyte [1]. It should also have a low temperature coefficient to minimize potential shifts with temperature changes [1].

- Common Materials: Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl), Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE), and Mercury/Mercuric Oxide (Hg/HgO) [1] [4]. For non-aqueous electrochemistry, pseudo-reference electrodes like a silver wire are also used, with their potential calibrated against an internal standard like ferrocene [3].

Counter Electrode (CE)

The Counter Electrode completes the electrical circuit, enabling current flow.

- Role: Also called the auxiliary electrode, the CE completes the current path and supplies/balances the current flowing to or from the working electrode [2] [3].

- Requirements: The counter electrode must be highly conductive and chemically stable to avoid unwanted side reactions [1]. It is typically chosen with a larger surface area than the working electrode to ensure that the current density is low, preventing it from becoming polarized and limiting the current [1] [4].

- Common Materials: Platinum wire or mesh, and graphite rods or plates [2] [1].

The following diagram illustrates the functional relationships and current flow within a standard three-electrode system.

(caption) Three-Electrode System Configuration. The potentiostat controls the WE potential versus the stable RE, while current flows between WE and CE.

Why a Three-Electrode System is Essential for Precise Research

The primary advantage of the three-electrode system over a two-electrode configuration is its ability to provide precise and unambiguous data. This is critical for advanced research techniques like cyclic voltammetry (CV), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and intermittent titration techniques (GITT/PITT) [2].

Precise Potential Control

The introduction of the reference electrode allows for independent measurement and control of the working electrode's potential without being influenced by the current flowing in the system. This greatly enhances experimental precision, especially when studying the kinetics and mechanisms of electrochemical reactions [2].

Elimination of Interfering Factors

In a two-electrode setup, voltage drops from solution resistance (known as the IR drop) and polarization of the counter electrode can obscure the true potential at the working electrode. The three-electrode cell, with its stable reference, eliminates much of this ambiguity, allowing researchers to more clearly separate and analyze different components within the electrochemical system [2].

Practical Evidence of Superiority

Comparative studies, particularly in sensing applications, demonstrate the practical benefits of the three-electrode system. For instance, research on a paper-based electrochemical aptasensor for dengue virus detection showed that the three-electrode setup had a substantially higher and more sensitive current response (ranging from 55.53 µA to 322.21 µA) compared to the two-electrode system (0.85 µA to 4.54 µA). This represents a current amplification of approximately 50 times, making the three-electrode method a more viable option for highly sensitive diagnostics [5].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Electrode Selection and Materials

Selecting the appropriate electrodes depends on several factors, including research objectives, electrolyte type (acidic, neutral, or alkaline), desired potential window, and sensitivity requirements [1]. The table below summarizes common choices for each electrode.

Table 1: Guide to Electrode Selection and Common Materials

| Electrode Type | Role & Key Characteristics | Common Materials & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode (WE) | Role: Site of the reaction of interest.Key Characteristics: Chemically inert, reproducible surface, controlled geometric area [2] [1]. | Glassy Carbon: Versatile; wide potential window [1].Platinum (Pt) & Gold (Au): Excellent conductivity; for electrocatalysis [1].Conductive Oxides (FTO/ITO): Essential for photoelectrochemistry [1]. |

| Reference Electrode (RE) | Role: Provides stable potential reference.Key Characteristics: Non-polarizable, stable and reproducible potential, minimal current draw [2] [1]. | Ag/AgCl: Very common for aqueous systems [1] [4].Saturated Calomel (SCE): Traditional standard for aqueous solutions [1] [4].Ag/Ag+ (non-aqueous): For organic solvent electrolytes [4]. |

| Counter Electrode (CE) | Role: Completes the current circuit.Key Characteristics: High conductivity, chemical stability, large surface area [2] [1]. | Platinum Mesh/Gauze: Inert, high surface area, ideal for most systems [1] [3].Graphite Rods: Cost-effective, chemically stable for long-duration tests [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Setting Up a Three-Electrode Cell for Cyclic Voltammetry

This protocol outlines the steps for assembling a standard three-electrode cell and conducting cyclic voltammetry (CV), a fundamental technique for studying redox reactions.

Materials and Equipment

- Electrochemical Workstation (Potentiostat): The central control and measurement unit.

- Electrochemical Cell: e.g., a 50 mL glass beaker or specialized cell jar.

- Electrodes: Working, reference, and counter electrodes, selected based on Table 1.

- Electrolyte Solution: A high-purity salt (e.g., KCl, Na₂SO₄) dissolved in a solvent (water or organic), typically at concentrations of 0.1 M to 1.0 M.

- Connecting Cables & Clips: Alligator clips or other connectors for secure contact.

- Polishing Supplies: For working electrode preparation, including alumina or diamond polishing powders and microcloth pads.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Working Electrode Preparation:

- Polishing: Polish the surface of the solid working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon) sequentially with progressively finer alumina slurries (e.g., 1.0 µm, 0.3 µm, 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad [3]. A mirror-finish is the goal.

- Rinsing: Rinse the electrode thoroughly with deionized water after each polishing step and after the final polish to remove all abrasive particles [3].

- Drying: Gently dry the electrode surface with a clean, lint-free tissue (e.g., Kimwipe) [6].

Cell Assembly:

- Add Electrolyte: Fill the electrochemical cell with the prepared electrolyte solution.

- Position Electrodes: Immerse the three electrodes into the electrolyte.

- Secure Connections: Use the connecting cables and clips to link the electrodes to the potentiostat. The red (working drive) and orange (working sense) leads are connected to the WE, the white (reference sense) lead to the RE, and the green (counter drive) lead to the CE [7].

Instrument Configuration:

- Turn on the potentiostat and connected computer.

- In the control software, select the cyclic voltammetry technique.

- Set the initial potential, upper vertex potential, and lower vertex potential based on the redox system under investigation.

- Set the scan rate (e.g., 50 mV/s or 100 mV/s). Multiple cycles are often run to check for reproducibility [3].

Running the Experiment and Data Acquisition:

- Initiate the CV scan. The instrument will automatically cycle the potential between the set limits.

- The potentiostat will record the current response at the working electrode, generating a current-potential plot known as a cyclic voltammogram.

- Run several cycles to ensure the signal is stable and reproducible [3].

Post-Experiment Shutdown and Cleaning:

- Once the experiment is complete, stop the measurement.

- Disconnect the electrodes from the potentiostat before removing them from the solution.

- Clean the working electrode according to material specifications and store all electrodes properly. Reference electrodes should be stored in an appropriate solution (e.g., Ag/AgCl in KCl) to prevent the porous frit from drying out [3].

Critical Troubleshooting Tips

- Non-Reproducible CVs: If consecutive cycles are not identical, the working electrode surface may be changing. Re-polish the electrode to ensure a clean, reproducible surface [3].

- Noisy or Unstable Signal: Check all electrical connections for secure contact. Ensure the counter electrode has a sufficiently large surface area to prevent polarization [1].

- Drifting Potential: This can indicate a faulty or contaminated reference electrode. Check the reference electrode's integrity and replace or refurbish it if necessary [3].

Advanced Applications in Research and Development

The three-electrode system's precision makes it indispensable across various advanced research fields.

- Battery Material Development: It is crucial for analyzing the electrochemical properties of electrode materials, such as diffusion coefficients and redox reaction rates. Techniques like GITT and PITT are used to optimize material design and battery performance [2] [4].

- Drug Development and Precision Medicine: Recent research combines conductive polymers with 3D printing to create electro-active drug delivery systems (DDS). These DDS use a three-electrode setup to apply precise voltages, enabling programmable, on-demand drug release profiles, which opens new avenues for personalized therapies [8].

- Biosensing: As demonstrated with the dengue virus aptasensor, the three-electrode system provides the sensitivity required for low-concentration detection of biological targets, making it valuable for medical diagnostics [5].

The three-electrode system is a cornerstone of modern electrochemical research. By separating the functions of potential measurement and current control, it provides an unparalleled level of precision for investigating redox reactions, characterizing new materials, and developing advanced diagnostic and therapeutic technologies. Its continued use is fundamental to progress in fields ranging from energy storage to precision medicine.

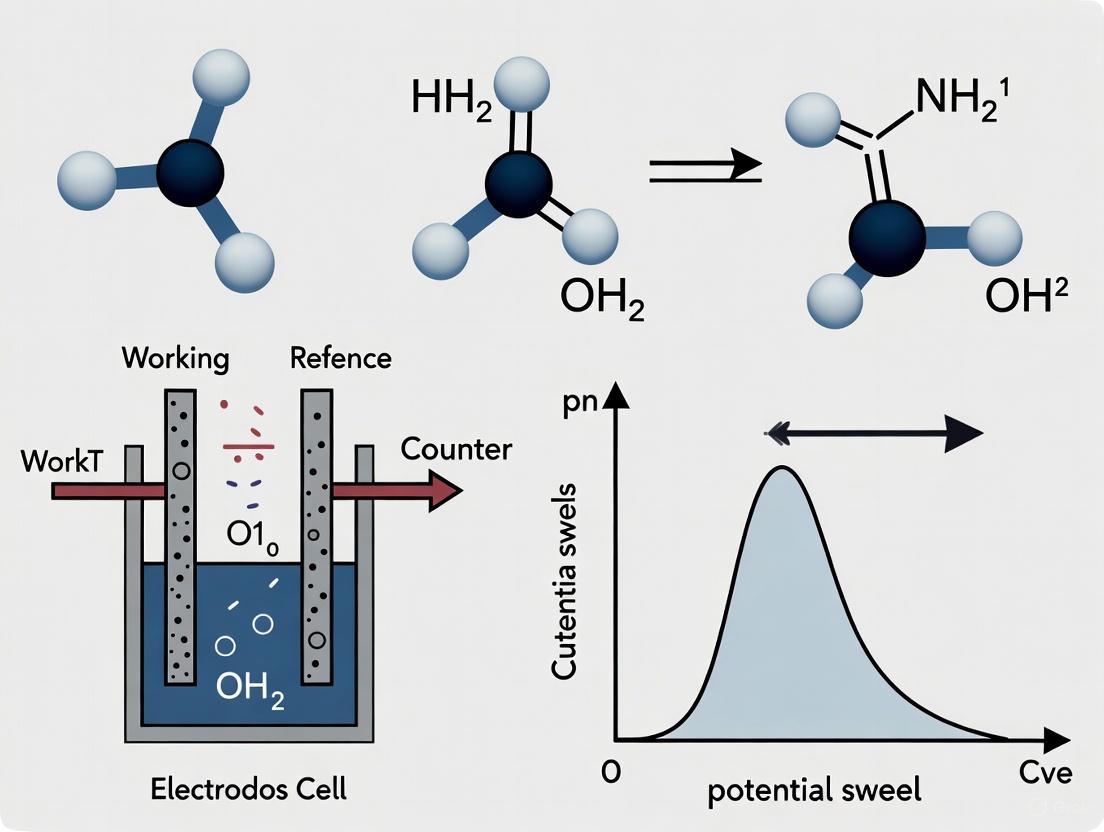

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) is a powerful and versatile electrochemical technique employed to rapidly elucidate information about the thermodynamics of redox processes, the energy levels of analytes, and the kinetics of electron-transfer reactions [9]. It is a fundamental method in the characterization of conductive polymers, battery materials, supercapacitors, fuel cell components, and pharmaceutical compounds [9] [10]. The technique involves measuring the current response of a redox-active solution to a linearly cycled potential sweep between the working and reference electrodes using a potentiostat [9]. The resulting plot of current versus potential often produces a characteristic "duck-shaped" profile, the cyclic voltammogram, which provides a wealth of qualitative and quantitative information to the trained researcher. This application note details the key features of this plot and outlines standardized protocols for its analysis within the context of redox reaction analysis research.

The Core Principles and Setup

The Three-Electrode System

A critical component of a reliable CV experiment is the three-electrode system, which separates the role of referencing the applied potential from the role of balancing the current produced [9].

- Working Electrode (WE): This is where the redox reaction of interest occurs. Its potential is varied linearly with time relative to the reference electrode. Common materials include glassy carbon, platinum, and gold.

- Reference Electrode (RE): This electrode maintains a fixed, well-known potential, providing a stable reference against which the working electrode's potential is controlled. Examples include Ag/AgCl and saturated calomel electrodes (SCE). It is designed to pass minimal current to avoid contamination and potential drift [9].

- Counter Electrode (CE): Also known as the auxiliary electrode, its primary function is to complete the electrical circuit by balancing the current generated at the working electrode. It typically has a larger surface area than the working electrode and is often made from an inert material like platinum wire [9].

The Potential Sweep and Redox Events

In a typical cyclic voltammetry experiment, the potentiostat sweeps the potential applied to the working electrode linearly over time. The scan starts at an initial potential, moves to a vertex potential, and then reverses direction to return to the initial potential [9]. During the forward sweep, if the potential is swept in a positive direction, an electroactive species may lose an electron in an oxidation (e.g., Fc → Fc⁺ + e⁻ for ferrocene). During the reverse sweep, the potential moves in a negative direction, and the oxidized species may gain an electron in a reduction (e.g., Fc⁺ + e⁻ → Fc) [9]. The current generated is a result of electron transfer between the redox species and the electrodes, and is carried through the solution by the diffusion and migration of ions, forming a capacitive electrical double layer at the electrode surface [9].

Deciphering the 'Duck-Shaped' Cyclic Voltammogram

The canonical "duck-shaped" voltammogram is the direct result of the processes described above. The current response is dependent on the concentration of the redox species at the working electrode surface, which is governed by diffusion [9]. The following walkthrough and diagram describe the formation of this shape.

Figure 1: The characteristic 'duck-shaped' cyclic voltammogram, showing the key points in the potential sweep and the corresponding electrochemical events at the working electrode [9].

- Point a: The initial potential is not sufficient to drive the oxidation or reduction of the analyte, resulting in negligible faradaic current [9].

- Point b: As the potential approaches the standard potential of the redox couple, the onset of oxidation (Eonset) is reached, and the current begins to increase exponentially [9].

- Point c: The current reaches a maximum, known as the anodic peak current (ipa), at the anodic peak potential (Epa). The current peak occurs because the depletion of the oxidant near the electrode surface (which decreases the current) begins to outweigh the effect of the increasing potential (which increases the current) [9].

- Point d: After the peak, the current decays as the system becomes limited by the mass transport of fresh analyte from the bulk solution to the electrode surface [9].

- Point e: Upon scan reversal, oxidation continues until the potential is sufficiently negative to reduce the oxidized species that have accumulated at the electrode surface [9].

- Point f: The cathodic peak current (ipc) is observed at the cathodic peak potential (Epc), corresponding to the reduction of the previously generated species [9].

Quantitative Data Analysis

The key quantitative parameters obtained from a cyclic voltammogram are the peak potentials (Ep) and the peak currents (ip), as illustrated in Figure 1 [11]. These parameters are used to determine the reversibility of a redox system and to calculate critical kinetic and thermodynamic properties.

Criteria for Reversibility

A redox system is considered electrochemically reversible if it remains in equilibrium throughout the potential scan, maintaining surface concentrations dictated by the Nernst equation [11]. The following criteria are used to assess reversibility:

Table 1: Diagnostic Criteria for a Reversible Redox Process in Cyclic Voltammetry [11].

| Parameter | Mathematical Relationship | Value at 25 °C |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Potential Separation | ΔEp = Epc - Epa | 59.2 / n mV |

| Peak Current Ratio | ipa / ipc | 1 |

| Scan Rate Dependence | ip / ν¹/² | Independent of scan rate (ν) |

The Randles-Sevcik Equation

For a reversible, diffusion-controlled process, the peak current (ip) is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte and the square root of the scan rate. This relationship is described by the Randles-Sevcik equation [9] [11].

At 298 K, the equation is: ip = (2.69 × 10⁵) n³/² A C D¹/² ν¹/²

Table 2: Parameters of the Randles-Sevcik Equation.

| Symbol | Parameter | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|

| ip | Peak Current | Amperes (A) |

| n | Number of electrons transferred per molecule | Dimensionless |

| A | Electrode surface area | cm² |

| C | Bulk concentration of the analyte | mol cm⁻³ |

| D | Diffusion coefficient | cm² s⁻¹ |

| ν | Potential scan rate | V s⁻¹ |

This relationship allows researchers to determine the diffusion coefficient (D) of an analyte or verify the number of electrons (n) transferred in a redox process if the other parameters are known [9].

Irreversible and Quasi-Reversible Processes

Departures from the ideal reversible behavior occur for two major reasons:

- Slow Electron Transfer Kinetics: If the electron transfer kinetics (denoted by the standard heterogeneous electron transfer rate constant, kₛ) are too slow to maintain Nernstian equilibrium at the scan rate (ν) used, the process is termed quasi-reversible. This is characterized by a peak potential separation (ΔEp) greater than 59.2/n mV, with the value increasing with increasing scan rate [11].

- Chemical Reactions of O and R: If the oxidized (O) or reduced (R) species undergoes a following chemical reaction, the voltammogram is distorted. This often manifests as a decrease in the peak current ratio (ipa/ipc < 1), as not all of the molecules reduced on the forward scan are available for reoxidation on the reverse scan [11].

Experimental Protocol: Basic CV Experiment

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for a Cyclic Voltammetry Experiment.

| Item | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat | Instrument to control potential and measure current. | Ossila Potentiostat, commercial systems. |

| Electrochemical Cell | Container for the electrolyte and analyte solution. | Glass vial or specialized cell. |

| Working Electrode | Site of the redox reaction; its material can affect reaction kinetics. | Glassy Carbon, Platinum, Gold disk. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for the working electrode. | Ag/AgCl, Saturated Calomel (SCE). |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the circuit; typically made from inert wire. | Platinum wire. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and minimizes resistive loss (iRu drop); must be electroinactive in the potential window of interest. | Tetraalkylammonium salts (e.g., TBAPF₆) in organic solvents; KCl in aqueous solutions. |

| Analyte | The redox-active species to be studied. | Ferrocene, pharmaceutical compounds, conductive polymers. |

| Solvent | Dissolves the electrolyte and analyte. | Acetonitrile (organic), Water (aqueous). |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the analyte (typically at concentrations of 1-10 mM) in a suitable solvent with a supporting electrolyte (typically 0.1 M) [9]. The supporting electrolyte concentration should be significantly higher than that of the analyte to ensure sufficient conductivity.

- Electrode Preparation: Clean the working electrode thoroughly according to the manufacturer's or established protocols (e.g., polishing on a microcloth with alumina slurry). Rinse the electrode with solvent and dry it [9].

- Setup: Place the solution into the electrochemical cell. Carefully insert the three electrodes into the cell, ensuring they are immersed in the solution but not touching each other.

- Instrument Configuration: On the potentiostat software, create a new cyclic voltammetry method. Set the parameters, which typically include:

- Initial Potential: The starting voltage (e.g., -0.4 V).

- High Vertex Potential: The most positive potential to be scanned.

- Low Vertex Potential: The most negative potential to be scanned.

- Scan Rate (ν): The rate at which the potential is changed (e.g., 0.1 V/s).

- Number of Scans: Often 2-3 scans are run to ensure a stable response.

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the scan. The potentiostat will control the potential and record the current, generating the cyclic voltammogram in real-time.

- Data Analysis: Once the scan is complete, use the software's analysis tools to mark the peak currents and peak potentials. Calculate the peak potential separation (ΔEp) and the peak current ratio (ipa/ipc) to assess reversibility [11]. Use the Randles-Sevcik equation for further quantitative analysis.

Advanced Application: Tafel Analysis for Kinetics

For electrochemically irreversible systems, Tafel analysis can be used to extract kinetic parameters such as the anodic (βa) and cathodic (βc) Tafel slopes, which are related to the electron transfer kinetics [12]. These are particularly important in fields like corrosion science and electrocatalysis.

Protocol: Generating a Tafel Plot from LSV Data

The following workflow outlines the process for transforming a Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) segment into a Tafel plot using software like AfterMath.

Figure 2: Workflow for generating a Tafel plot and extracting Tafel slopes from LSV data [12].

- Data Preparation: Begin with a single-segment LSV. If your data is from a multi-segment CV, you must first extract the segment of interest (e.g., the forward scan) into a new LSV plot to preserve the original data [12].

- Axis and Unit Adjustment (Optional): The corrosion community often plots potential on the Y-axis and current density on the X-axis. Use a "Basic Math Operations" transform to swap the X and Y axes if needed. Convert current to current density by dividing the current values by the geometric area of the working electrode [12].

- Tafel Transformation: Apply a "Basic Math Operations" transform to the axis displaying current. Select the "Tafel log (|x|)" function, which calculates the base-10 logarithm of the absolute value of the current (or current density) [12]. The result is a Tafel plot (Potential vs. log |i|).

- Slope Determination: Use the software's "Baseline" tool to select the linear regions of the Tafel plot. The slope of the anodic branch is βa, and the slope of the cathodic branch is βc. These empirical values can be used in subsequent calculations, such as for corrosion rates in Linear Polarization Resistance (LPR) experiments [12].

The cyclic voltammogram serves as a fundamental fingerprint for redox-active species, providing deep insight into electrochemical behavior. By understanding its key features—the peak potentials, peak currents, and their relationships—researchers can determine the reversibility of a reaction, quantify kinetic parameters, and diagnose coupled chemical reactions. Adherence to standardized protocols for both basic CV experimentation and advanced data transformation, such as Tafel analysis, ensures the generation of robust, reproducible, and meaningful data. This is indispensable for advancing research in drug development, energy storage, materials science, and beyond.

The Nernst equation is a fundamental principle in electrochemistry that precisely relates the reduction potential of an electrochemical reaction to the standard electrode potential, temperature, and the activities (or concentrations) of the chemical species involved [13] [14]. For researchers utilizing cyclic voltammetry (CV), this equation provides the critical thermodynamic link between the measured potential in a voltammogram and the actual concentration of redox species at the electrode surface, enabling the quantification of reaction spontaneity and the determination of equilibrium constants [13] [15].

In the context of analyzing redox reactions, the Nernst equation describes the potential at which a redox couple exists at equilibrium at the electrode-solution interface. During a cyclic voltammetry experiment, where the electrode potential is linearly swept, the Nernst equation dictates how the relative concentrations of the oxidized (O) and reduced (R) forms of an analyte adjust instantaneously at the electrode surface to maintain equilibrium with the applied potential, assuming a reversible (fast) electron transfer process [16] [17]. This relationship is the cornerstone for interpreting the peak potentials and shapes of cyclic voltammograms, which in turn reveal vital information about the thermodynamics and kinetics of the system under study [18] [19].

Core Principles and Quantitative Relationships

The Fundamental Equation

The Nernst equation is derived from the relationship between the Gibbs free energy change under non-standard conditions and the electrical work that a cell can perform [13] [20]. For a general reversible redox reaction:

[ \text{O} + n\text{e}^- \rightleftharpoons \text{R} ]

The Nernst equation is expressed in its most general form as:

[ E = E^\circ - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q ]

or, for the specific reaction above:

[ E = E^\circ - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{a{\text{R}}}{a{\text{O}}} ]

where:

- ( E ) is the actual cell potential or half-cell potential (Volts, V)

- ( E^\circ ) is the standard cell potential or formal potential (V)

- ( R ) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹)

- ( T ) is the absolute temperature (Kelvin, K)

- ( n ) is the number of electrons transferred in the redox reaction

- ( F ) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹)

- ( Q ) is the reaction quotient

- ( a{\text{R}} ) and ( a{\text{O}} ) are the chemical activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [13] [14]

At room temperature (298.15 K or 25 °C), and converting from natural logarithm to base-10 logarithm, the equation simplifies to the widely used form:

[ E = E^\circ - \frac{0.0592}{n} \log \frac{[\text{R}]}{[\text{O}]} ]

Here, the activities are often approximated by concentrations (in mol·L⁻¹) for dilute solutions, a common condition in analytical experiments [13] [15]. This simplified version is exceptionally valuable for rapid, manual calculations.

Linking Potential, Free Energy, and Equilibrium

The Nernst equation is intrinsically connected to other key thermodynamic parameters, as summarized in the table below. These relationships allow researchers to extract comprehensive thermodynamic information from electrochemical measurements like cyclic voltammetry [13] [15].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Relationships in Electrochemistry

| Parameter | Mathematical Relationship | Significance in Redox Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Free Energy Change (( \Delta G^\circ )) | ( \Delta G^\circ = -nFE^\circ ) [15] | A negative ( \Delta G^\circ ) (positive ( E^\circ )) indicates a spontaneous reaction under standard conditions [15]. |

| Free Energy Change (( \Delta G )) | ( \Delta G = -nFE ) [13] [20] | The actual Gibbs energy change under non-standard conditions determines reaction spontaneity. |

| Equilibrium Constant (( K )) | ( \log K = \frac{nE^\circ}{0.0592} ) (at 298 K) [13] | Relates the standard cell potential directly to the thermodynamic equilibrium constant. A large ( K ) indicates the reaction proceeds far towards products [13] [15]. |

Table 2: Predicting Reaction Spontaneity from Potential and Composition

| Condition | Relationship | Reaction Spontaneity & Direction |

|---|---|---|

| Under Standard Conditions | ( Q = 1 ), ( E = E^\circ ) | If ( E^\circ > 0 ), reaction is spontaneous. If ( E^\circ < 0 ), reaction is non-spontaneous [15]. |

| At Equilibrium | ( Q = K ), ( E = 0 ) | No net reaction; the system is at equilibrium [13]. |

| Non-Standard Conditions | ( E = E^\circ - \frac{0.0592}{n} \log Q ) | If ( E > 0 ), reaction is spontaneous as written. If ( E < 0 ), reaction is spontaneous in the reverse direction [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Applying the Nernst Equation in Cyclic Voltammetry

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Cyclic Voltammetry

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat | Instrument that controls the potential between the working and reference electrodes and measures the resulting current [18]. |

| Three-Electrode System | Standard setup: a Working Electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, platinum) where the reaction of interest occurs, a Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) that provides a stable, known potential, and a Counter (Auxiliary) Electrode (e.g., platinum wire) that completes the circuit [9] [18]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | A high-concentration, electrochemically inert salt (e.g., TBAPF₆, NaClO₄). Its primary function is to conduct current and minimize the effects of migratory mass transport, ensuring diffusion is the dominant mode of analyte transport [9]. |

| Redox-Active Analyte | The molecule or species under investigation (e.g., ferrocene, a quinone, a metal complex). It must be purified and of known, high purity for accurate quantitative analysis. |

| Solvent | A solvent suitable for electrochemical studies (e.g., acetonitrile, DMF, aqueous buffer). It must dissolve the analyte and electrolyte and have an appropriately wide electrochemical "window" where it is neither oxidized nor reduced within the potential range of interest [9]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Part A: Sample and Electrode Preparation

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing your redox-active analyte (typically 1-5 mM) in a suitable solvent. Add the supporting electrolyte at a significantly higher concentration (typically 0.1-0.2 M) to ensure sufficient conductivity [9].

- Electrode Preparation: Carefully polish the working electrode (e.g., a 3 mm diameter glassy carbon electrode) with successively finer alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with the purified solvent and then with the electrolyte solution to remove any polishing residue [18].

- Cell Assembly: Place the solution into a clean electrochemical cell. Insert the three electrodes, ensuring they are fully immersed. If necessary, purge the solution with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for at least 10-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the measurement, and maintain a gentle gas blanket over the solution during the experiment.

Part B: Instrument Setup and Data Acquisition

- Potentiostat Connection: Connect the working, reference, and counter electrodes to the corresponding leads of the potentiostat.

- Parameter Configuration: Open the control software and set up the cyclic voltammetry experiment with the following parameters [17] [19]:

- Initial Potential (Eᵢ): A potential where no faradaic current flows (e.g., 0 V vs. Ag/AgCl for ferrocene).

- Scan Range (Eλ): Set upper and lower switching potentials that comfortably bracket the expected redox event(s).

- Scan Rate (v): Begin with a moderate scan rate, such as 100 mV/s.

- Data Collection: Initiate the potential sweep. The potentiostat will apply the linear potential waveform and record the current response, generating a cyclic voltammogram (CV). For a reversible system, this will typically produce the characteristic "duck-shaped" CV with symmetrical oxidation and reduction peaks [9] [19].

Part C: Data Analysis Using the Nernst Equation

- Determine the Formal Potential (E°'): For a reversible couple, the formal potential (E°') is calculated as the midpoint between the anodic (Epa) and cathodic (Epc) peak potentials [19]: [ E^{\circ'} = \frac{E{pa} + E{pc}}{2} ]

- Verify Nernstian Behavior: Confirm the system is electrochemically reversible by checking that the peak separation (ΔEp = Epa - Epc) is close to 59/n mV at 25 °C and that the peak current ratio (Ipa/Ipc) is approximately 1 [17] [19].

- Calculate Concentration Ratios: Use the Nernst equation to determine the ratio of oxidized to reduced species at the electrode surface at any point during the potential sweep. For example, at the foot of the wave, you can calculate the tiny fraction of analyte that has been oxidized or reduced [16].

- Determine the Equilibrium Constant (K): If studying a coupled chemical equilibrium, use the formal potential shift to calculate the equilibrium constant for the chemical step using the relationships in Table 1 [13] [15].

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflow

The Nernst Equation in a Cyclic Voltammetry Experiment

The following diagram illustrates how the Nernst equation governs the changing concentrations of redox species at the electrode surface during a cyclic voltammetry sweep, leading to the characteristic current response.

Experimental Workflow for CV-based Thermodynamic Analysis

This workflow outlines the key experimental and analytical steps for using cyclic voltammetry and the Nernst equation to determine thermodynamic parameters.

The Randles-Ševčík equation is a fundamental principle in electrochemistry that quantitatively describes the peak current response in cyclic voltammetry (CV) experiments for reversible, diffusion-controlled redox reactions [21] [22]. This equation provides a critical link between experimentally measurable parameters (peak current) and intrinsic properties of the electroactive species, such as its diffusion coefficient [23]. For researchers in redox reaction analysis and drug development, it serves as an indispensable tool for quantifying electrochemical processes, characterizing new compounds, and verifying experimental conditions [24].

The equation was independently derived in 1948 by John Edward Brough Randles and Antonín Ševčík during post-war advancements in electroanalytical techniques, which shifted focus from steady-state polarography to dynamic studies of redox kinetics [22]. Its development enabled quantitative analysis of electrochemical systems without complex numerical simulations, making it a cornerstone technique that remains widely applied in materials science, biosensor development, and pharmaceutical research [22].

Theoretical Foundation

Mathematical Formulations

The Randles-Ševčík equation is derived from Fick's laws of diffusion under conditions where electron transfer kinetics are rapid relative to mass transport (electrochemically reversible systems) [21] [22]. The general form of the equation is:

$$i_p = 0.4463 \, nFAC \left( \frac{nF \nu D}{RT} \right)^{1/2}$$

For practical applications at standard laboratory temperature (25°C), the equation simplifies to:

$$i_p = (2.69 \times 10^5) \, n^{3/2} A D^{1/2} C \nu^{1/2}$$

The following table details all parameters and their units required for applying the Randles-Ševčík equation.

Table 1: Parameters in the Randles-Ševčík Equation

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Current | (i_p) | Amperes (A) | Maximum current observed during potential sweep |

| Number of Electrons | (n) | Dimensionless | Electrons transferred in redox event |

| Electrode Area | (A) | cm² | Electroactive surface area of working electrode |

| Diffusion Coefficient | (D) | cm²/s | Measure of species mobility in solution |

| Concentration | (C) | mol/cm³ | Bulk concentration of electroactive species |

| Scan Rate | (\nu) | V/s | Rate of potential sweep |

| Faraday Constant | (F) | C/mol | Electrical charge per mole of electrons (96485 C/mol) |

| Gas Constant | (R) | J/(mol·K) | Universal gas constant (8.314 J/(mol·K)) |

| Temperature | (T) | K | Absolute temperature |

Diagnostic Applications for Reaction Mechanisms

The relationship (i_p \propto \nu^{1/2}) provides critical diagnostic power for distinguishing reaction mechanisms. A linear plot of peak current versus the square root of scan rate indicates a diffusion-controlled process with freely diffusing species [23] [25]. Deviations from this linearity suggest alternative mechanisms:

- Surface-adsorbed species: Electron transfer occurs through molecules attached to the electrode surface rather than freely diffusing [25].

- Quasi-reversible or irreversible kinetics: Electron transfer rates become slow relative to the scan rate [24].

- Electrochemical irreversibility: The redox reaction is not reversible, invalidating the equation's assumptions [25].

For quasi-reversible systems (typically 63 mV < nΔEp < 200 mV), a modified Randles-Ševčík equation incorporating a dimensionless kinetic parameter K(Λ,α) must be used [24]:

$$I_p = (2.69 × 10^5 \, n^{3/2} A D C \nu^{1/2}) K(Λ,α)$$

The following diagram illustrates the diagnostic workflow for interpreting cyclic voltammetry data using the Randles-Ševčík equation.

Experimental Protocols

Determining Diffusion Coefficients

Purpose: Calculate the diffusion coefficient (D) of an electroactive species using the Randles-Ševčík equation [21] [23].

Materials:

- Standard redox probe with known behavior (e.g., 1.0 mM potassium ferricyanide in 1.0 M KCl)

- Supporting electrolyte appropriate for your system

- Three-electrode electrochemical cell

- Potentiostat with cyclic voltammetry capability

- Working electrode with known electroactive area

Procedure:

- Prepare an electrochemical cell containing your analyte at known concentration in supporting electrolyte [24].

- Record cyclic voltammograms at multiple scan rates (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 mV/s) [24].

- For each voltammogram, measure the peak current (ip) for the oxidation or reduction wave.

- Plot ip versus ν1/2.

- Perform linear regression on the data. The slope (m) of this plot relates to the diffusion coefficient:

$$D = \left( \frac{\text{slope}}{2.69 \times 10^5 \, n^{3/2} A C} \right)^2$$

Validation: The plot of ip versus ν1/2 should be linear with a correlation coefficient (R²) >0.995, and the peak potential separation (ΔEp) should be close to 59/n mV for a reversible system [24].

Calculating Electroactive Surface Area

Purpose: Determine the electroactive area (A) of a working electrode, which often differs from its geometric area [23] [24].

Materials:

- Standard redox couple with known diffusion coefficient (e.g., 1.0 mM ferrocene in acetonitrile with 0.1 M TBAPF6 as supporting electrolyte)

- Supporting electrolyte

- Electrochemical cell and potentiostat

- Electrode to be characterized

Procedure:

- Record cyclic voltammograms of the standard solution at multiple scan rates.

- Measure the peak current (ip) for each scan rate.

- Plot ip versus ν1/2 and determine the slope.

- Calculate the electroactive area using:

$$A = \frac{\text{slope}}{2.69 \times 10^5 \, n^{3/2} D^{1/2} C}$$

Applications: This protocol is essential for characterizing modified electrodes, assessing electrode fouling, and validating electrode cleaning procedures [23] [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines essential materials and their functions for experiments utilizing the Randles-Ševčík equation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Redox Probes | Reference compounds for method validation | 1-5 mM potassium ferricyanide, ferrocene, or ruthenium hexamine [24] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimize migration effects, provide conductivity | 0.1-1.0 M KCl, TBAPF6, or other salts [24] |

| Working Electrodes | Platform for redox reactions | Glassy carbon, gold, or platinum electrodes [26] [23] |

| Potentiostat | Instrument for applying potential and measuring current | Capable of cyclic voltammetry with adjustable scan rates [27] |

| Solvents | Dissolve analytes and electrolytes | Acetonitrile, water, DMF; purified and deoxygenated [24] |

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Analytical Research

Antioxidant Capacity Assessment

Cyclic voltammetry combined with the Randles-Ševčík equation provides a powerful method for evaluating antioxidant potential in natural products and pharmaceuticals [28] [29]. Recent studies have successfully correlated anodic current measurements with traditional antioxidant assays (DPPH, ABTS), offering insights into electron-donating capabilities of bioactive compounds [28]. The peak current directly relates to antioxidant concentration and strength, while the peak potential indicates the reducing power [28]. This approach has been applied to characterize vegetable extracts, protein hydrolysates, and medicinal plants, supporting drug development from natural sources [29].

Characterization of Complex Systems

The equation facilitates quantitative analysis of complex interactions relevant to pharmaceutical sciences. Research on mercuric chloride interactions with Orange G dye demonstrated how scan rate studies combined with the Randles-Ševčík relationship can elucidate complexation behavior and determine stability constants [26]. Such approaches help understand how toxic compounds interact with biological molecules, contributing to environmental monitoring and pharmaceutical safety assessments [26].

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

Recent methodological advances continue to expand the equation's applications. Novel techniques like opto-iontronic microscopy now enable monitoring electrochemical processes at nanoscale volumes, validating theoretical models including the Randles-Ševčík relationship in confined environments [30]. Such developments open possibilities for high-sensitivity analysis with potential applications in single-molecule electrochemistry relevant to drug discovery [30].

Critical Considerations and Method Validation

System Requirements and Limitations

Researchers must verify key assumptions before applying the Randles-Ševčík equation:

- Reversibility: The redox system must be electrochemically reversible (fast electron transfer kinetics) [21] [22].

- Diffusion control: Mass transport must occur primarily through diffusion, not convection or adsorption [25].

- No competing reactions: The system should contain only the redox reaction of interest [21].

- Planar electrode: The equation assumes semi-infinite linear diffusion to a planar electrode surface [22].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for diagnosing and addressing common problems in Randles-Ševčík analysis.

Data Interpretation Guidelines

For reliable results, researchers should:

- Use at least five different scan rates covering at least an order of magnitude (e.g., 10-500 mV/s) [24].

- Ensure consistent temperature control, as diffusion coefficients are temperature-dependent.

- Verify electrode cleanliness between experiments, as fouling significantly affects electroactive area [23].

- Confirm the absence of background currents that could interfere with peak current measurements.

- Validate findings with complementary techniques when characterizing new systems [24].

When properly applied and validated, the Randles-Ševčík equation provides robust quantitative analysis of redox systems, contributing significantly to pharmaceutical development, materials characterization, and fundamental electrochemical research.

Distinguishing Reversible, Irreversible, and Quasi-reversible Electron Transfer Processes

In the analysis of redox reactions using cyclic voltammetry (CV), categorizing the nature of electron transfer is a fundamental step in interpreting electrochemical data and understanding underlying reaction mechanisms. The terms reversible, irreversible, and quasi-reversible describe the kinetic facility of electron transfer between the electrode and electroactive species [31] [32]. For researchers in drug development, accurately distinguishing these processes is critical, as electron transfer kinetics can influence the stability, reactivity, and redox properties of pharmaceutical compounds. A reversible process indicates fast electron transfer kinetics where the redox couple rapidly establishes equilibrium at the electrode surface at each potential. In contrast, an irreversible process features slow electron transfer, requiring significant overpotential to drive the reaction. The quasi-reversible category encompasses an intermediate regime where both electron transfer kinetics and mass transport influence the voltammetric response [31]. This application note provides a structured framework for distinguishing these electron transfer processes through defined diagnostic parameters and experimental protocols.

Theoretical Foundations and Diagnostic Criteria

Fundamental Definitions

Electrochemical Reversibility: This concept specifically refers to the kinetics of heterogeneous electron transfer at the electrode-solution interface [32]. A system is considered electrochemically reversible when the electron transfer rate is sufficiently high to maintain Nernstian equilibrium at the electrode surface throughout the potential scan [31]. This is distinct from chemical reversibility, which concerns the stability of the redox-generated species to subsequent chemical reactions [32].

Chemical Reversibility: A system is chemically reversible if the electrogenerated species (e.g., the reduced form "Red" produced from the oxidized form "Ox") is stable on the experimental timescale and can be converted back to its original form during the reverse potential scan [32]. When the product undergoes a subsequent irreversible chemical reaction (e.g., R → Z), the system is deemed chemically irreversible, often manifesting as the disappearance of the return peak in CV [31] [33].

Quantitative Diagnostic Parameters

The following parameters, derived from analysis of cyclic voltammograms, serve as primary diagnostics for classifying electron transfer processes.

Table 1: Diagnostic Criteria for Classifying Electron Transfer Processes in Cyclic Voltammetry

| Parameter | Reversible | Quasi-Reversible | Irreversible |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Separation (ΔEp) | ≈ 59/n mV (at 25°C) [33] | > 59/n mV [33] | > 59/n mV, significantly larger [31] |

| Scan Rate Dependence of Ep | Constant [34] | Shifts with scan rate [31] | Shifts with scan rate; linear with log(ν) [34] |

| Peak Current Ratio (ipa/ipc) | ≈ 1 [33] | Near 1 (but shape changes) [31] | Deviates from 1 [31] |

| Current Function (ip/ν1/2) | Constant [33] | Decreases with increasing ν [31] | Varies, lower magnitude |

| Rate Constant, k° (cm/s) | Large (> ~0.1-1 cm/s) [33] | Intermediate (~10-5 to 10-1) [31] | Small (< ~10-5) [31] |

Conceptual Workflow for Classification

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for classifying an electron transfer process based on cyclic voltammetry data.

Figure 1: Decision workflow for classifying electron transfer processes from CV data.

Experimental Protocols for Distinction

Protocol 1: Multi-Scan Rate CV Analysis

Purpose: To determine the effect of scan rate on peak potential and current, which is crucial for classifying electron transfer reversibility [34].

Materials:

- Potentiostat with standard three-electrode cell setup

- Working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, Pt disk)

- Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl, SCE)

- Counter electrode (Pt wire)

- Electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M KNO3, PBS)

- Analyte of interest (e.g., 1-5 mM concentration)

Procedure:

- Prepare the electrochemical cell with analyte dissolved in supporting electrolyte.

- Polish the working electrode (if solid) to a mirror finish using alumina slurry (1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm sequentially) and rinse thoroughly with deionized water [34].

- Set the initial potential at least 200 mV more positive (for reduction) or negative (for oxidation) than the expected formal potential (E°).

- Define the switching potential at least 200 mV beyond the observed peak potential.

- Record CVs at a series of scan rates (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500 mV/s).

- For each voltammogram, measure the anodic peak potential (Epa), cathodic peak potential (Epc), anodic peak current (ipa), and cathodic peak current (ipc).

Data Analysis:

- Calculate ΔEp = Epa - Epc for each scan rate.

- Plot Ep versus log(ν) for both anodic and cathodic peaks.

- Plot ip versus ν1/2 to verify diffusion control.

- Plot log(ip) versus log(ν); the slope should be approximately 0.5 for diffusion-controlled processes.

Interpretation:

- If ΔEp is close to 59/n mV and independent of scan rate, the system is reversible [34].

- If ΔEp > 59/n mV and increases with scan rate, and Ep shifts linearly with log(ν) with a slope of approximately ±60/αn mV/decade, the system is irreversible [34].

- For quasi-reversible systems, ΔEp is greater than 59/n mV and increases with scan rate, but the peaks remain well-defined [31].

Protocol 2: Determining Heterogeneous Electron Transfer Rate Constant (k°)

Purpose: To quantify the standard heterogeneous electron transfer rate constant, which provides a numerical basis for classifying electron transfer processes [35].

Materials: Same as Protocol 1, with emphasis on careful control of experimental conditions.

Procedure:

- Follow steps 1-4 from Protocol 1, ensuring excellent electrode preparation and ohmic drop compensation.

- For reversible systems, k° can be estimated from the scan rate (νrev) at which the system begins to deviate from reversibility using the relationship: k° ≈ 0.3(νrevnF/RT)1/2 [33].

- For quasi-reversible systems, record CVs across a wide range of scan rates (e.g., 0.01 to 100 V/s if accessible).

- Use square-wave voltammetry (SWV) as a complementary technique by scanning frequency and amplitude, then fitting data to a model incorporating Butler-Volmer kinetics [35].

Data Analysis using Numerical Simulation:

- Model the electrochemical cell using Fick's second law of diffusion: ∂CO/∂t = DO∇2CO and ∂CR/∂t = DR∇2CR [35].

- Apply Butler-Volmer kinetics as a boundary condition at the electrode surface: Flux = -k°[e-αnF/RT(E-E°)CO(0,t) - e(1-α)nF/RT(E-E°)CR(0,t)] [35].

- Iteratively adjust k° and α in simulations to minimize the difference between simulated and experimental voltammograms.

Classification Criteria:

- Reversible: k° > 0.1-1 cm/s [33]

- Quasi-reversible: 10-5 < k° < 0.1 cm/s [31]

- Irreversible: k° < 10-5 cm/s [31]

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Analysis

The complete experimental pathway for characterizing electron transfer processes is illustrated below.

Figure 2: Comprehensive experimental workflow for characterizing electron transfer processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Electron Transfer Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides ionic conductivity; minimizes ohmic drop; controls ionic strength | 0.1 M KNO3, PBS buffer, TBAPF6 in organic solvents |

| Standard Redox Couples | System validation and calibration | 1.0 mM K3Fe(CN)6 in 1.0 M KNO3 (reversible benchmark) [33] |

| Electrode Polishing Kit | Ensines reproducible electrode surface morphology | Alumina slurry (1.0, 0.3, 0.05 µm); polishing pads |

| Potentiostat | Applies potential waveform and measures current | Commercial instrument with scan rates from 0.1 mV/s to 10,000 V/s |

| Faradaic Cage | Minimizes external electromagnetic interference | Enclosed metal enclosure grounded to potentiostat |

| Solvent Systems | Dissolves analytes of varying polarity | Acetonitrile (non-aqueous), Water (aqueous), DMF |

| Numerical Simulation Software | Extracts kinetic parameters from voltammetric data | DIGISIM, COMSOL, or custom finite-difference algorithms [35] |

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Square-Wave Voltammetry for Kinetic Analysis

For particularly challenging systems with very fast or very slow electron transfer, square-wave voltammetry (SWV) provides enhanced sensitivity for kinetic analysis [35]. This technique applies a series of square-wave pulses superimposed on a staircase ramp, effectively discriminating against capacitive currents. The relationship between square-wave frequency and peak current provides quantitative information about electron transfer rates, extending the measurable range of k° values beyond what is accessible through CV alone [35]. The numerical simulation approach described in Protocol 2 can be adapted for SWV data by modeling the more complex potential waveform.

Distinguishing Chemical vs. Electrochemical Irreversibility

A critical challenge in interpreting irreversible voltammetric responses is distinguishing between slow electron transfer kinetics (electrochemical irreversibility) and rapid chemical reaction of the electrogenerated species (chemical irreversibility) [31] [32]. This distinction has significant implications in drug development, where chemical irreversibility may indicate metabolic instability or reactive metabolite formation.

Diagnostic Approach:

- Systematic scan rate studies: In chemically irreversible systems following an EC mechanism (Electron transfer followed by Chemical step), the ratio of reverse-to-forward peak currents (ip,rev/ip,fwd) decreases with decreasing scan rate, as the chemical step has more time to consume the electrogenerated species [33].

- Controlled potential electrolysis with product analysis: Bulk electrolysis at the peak potential followed by analytical characterization (e.g., HPLC, NMR) of the solution can identify decomposition products.

- Variable time scale experiments: Using ultramicroelectrodes to access shorter experimental time scales can sometimes reveal reversibility that is masked at conventional time scales.

Accurate classification of electron transfer processes as reversible, quasi-reversible, or irreversible provides fundamental insights into redox behavior that is essential for research in electrochemistry, materials science, and drug development. The protocols and diagnostic criteria outlined in this application note establish a systematic approach for distinguishing these processes through multi-scan rate cyclic voltammetry, complemented by numerical simulation to extract quantitative kinetic parameters. For researchers in pharmaceutical development, this classification not only characterizes electron transfer kinetics but also reveals potential chemical reactivity of redox-generated species, informing drug stability and metabolic fate predictions. The experimental workflows and decision trees presented here offer a standardized methodology applicable across diverse research domains where understanding electron transfer is critical.

The Electric Double Layer (EDL) and Its Role in Electrode-Solution Interfaces

The Electrical Double Layer (EDL) is a fundamental concept in electrochemistry, describing the structured arrangement of ions and molecules that forms at the interface between an electrode and an electrolyte solution. This region is critical because its properties govern the reactivity, capacitance, and electron-transfer kinetics of electrochemical processes. When a charged electrode is immersed in an electrolyte, ions from the solution arrange themselves to screen the surface charge. This creates a complex interface consisting of a compact layer of strongly adsorbed ions (the Stern layer) and a diffuse layer where ions are mobile, influenced by both electrostatic forces and diffusion [36]. A detailed understanding of the EDL is indispensable for interpreting electrochemical techniques, notably cyclic voltammetry (CV), a cornerstone method for analyzing redox reactions. The structure and dynamics of the EDL directly influence key CV parameters, such as peak currents, peak potentials, and the overall shape of the voltammogram, thereby providing crucial insights into reaction thermodynamics and kinetics [37] [36].

Theoretical Foundations of the EDL

The classical Gouy-Chapman-Stern (GCS) model provides a foundational, though simplified, description of the EDL. This model partitions the interface into two main regions: the inner Stern layer (or Helmholtz layer), comprising ions specifically adsorbed and immobilized on the electrode surface, and the outer diffuse layer, where a cloud of mobile ions screens the remaining surface charge [36]. The entire EDL can be electrically represented as a capacitance, often modeled as the Stern capacitance and the diffuse layer capacitance acting in series [36].

However, advanced computational studies reveal that the real picture is more complex. The EDL is not a simple mean-field structure but is highly dependent on molecular-scale interactions. For instance, at metal oxide-electrolyte interfaces, the surface charge is not uniform but is determined by the protonation and deprotonation of specific surface sites, which is highly sensitive to the pH of the solution relative to the point of zero charge (pHPZC) [38]. Ab initio machine learning potential simulations have shown that the charging mechanisms can differ significantly under acidic versus basic conditions, leading to distinct capacitive behaviors [38]. Furthermore, the properties of the first few layers of water at the interface deviate substantially from bulk water, a nuance that continuum models like GCS cannot capture [38]. These molecular-scale insights are crucial for a accurate interpretation of electrochemical data.

Quantitative EDL Data from Experimental and Simulation Studies

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings on EDL properties from recent research, highlighting the impact of material, solution conditions, and measurement technique.

Table 1: EDL Capacitance from Various Studies

| Electrode Material | Electrolyte | pH (vs. pHPZC) | Capacitance | Measurement Technique | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatase TiO₂ | 0.4 M NaCl | Acidic (pH < pHPZC) | ~7.69 µC/cm² (Surface Charge) | DPLR Molecular Simulation | [38] |

| Anatase TiO₂ | 0.4 M NaCl | Basic (pH > pHPZC) | ~7.54 µC/cm² (Surface Charge) | DPLR Molecular Simulation | [38] |

| Planar Electrode | Aqueous Solution | N/A | Constant at low scan rates | CV with MPNP Model | [36] |

Table 2: Impact of EDL on Redox Kinetics (Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻ System)

| Electrode Structure | EDL Characteristics | Electron Transfer Kinetics | Observed Peak Potential Separation (ΔEₚ) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag Monolayer on Au | Similar to bulk Ag EDL | Corresponds to Au electrode | Standard for a reversible system | [37] |

| Ag Multilayer on Au | Forms Ag Hexacyanoferrate (II) film | Altered by ohmic film resistance | Increases with number of Ag layers | [37] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for investigating the EDL using cyclic voltammetry and an advanced optical technique.

Protocol: Probing EDL Effects Using a Model Redox Couple

This protocol uses the Ferricyanide/Ferrocyanide (Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻) redox couple to characterize the EDL and electron transfer kinetics on modified electrodes [37].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Supporting Electrolyte: 1 M KNO₃ in triply-distilled water.

- Redox Probe: Potassium ferricyanide (K₃Fe(CN)₆) in the supporting electrolyte.

- Electrode Cleaning Solution: 0.5 M H₂SO₄.

- Electrode Modification Electrolyte: 0.1 M NaF, adjusted to pH 5 with sulfuric acid.

- Silver Plating Solution: Ag⁺ ions in the NaF electrolyte.

Procedure

- Working Electrode Preparation: Begin with a polycrystalline gold wire working electrode (e.g., 0.7 mm diameter). Polish the electrode mechanically with 0.3 µm alumina powder. Subsequently, electro-polish in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ to achieve a pristine surface [37].

- Electrode Modification (Silver Deposition):

- Immerse the clean Au working electrode in the Ag⁺-containing NaF electrolyte (pH 5).

- Use an underpotential deposition protocol to deposit a monolayer of silver atoms. For multilayer deposits, continue the electrodeposition process.

- Characterize the deposit using techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to confirm surface coverage and morphology [37].

- Cyclic Voltammetry Measurement:

- Transfer the modified electrode to an electrochemical cell containing the Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻ solution in 1 M KNO₃.

- Use a standard three-electrode setup with a Pt counter electrode and a suitable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl).

- Record cyclic voltammograms over a suitable potential window (e.g., -0.2 V to 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl) at multiple scan rates (e.g., from 10 mV/s to 500 mV/s) [37].

- Data Analysis:

- Kinetics Analysis: For a monolayer Ag deposit, the EDL structure is like bulk silver, but the electron transfer kinetics will still reflect the underlying gold substrate [37].

- Ohmic Effects Analysis: For multilayer Ag deposits, an increase in the peak potential separation (ΔEₚ) with deposit thickness is not due to slowed kinetics but to the increased ohmic resistance of a formed silver hexacyanoferrate (II) film. This can be confirmed with the Randles-Sevcik equation; a linear relationship between peak current and the square root of scan rate confirms a diffusion-controlled process despite the resistive layer [37].

Protocol: Opto-iontronic Microscopy for Nanoscale EDL Dynamics

This advanced protocol leverages optical microscopy to directly monitor EDL charging and coupled redox reactions within nanoconfined volumes, providing unprecedented spatial resolution [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

- Electrolyte and Redox Probe: 1,1-Ferrocenedimethanol (Fc(MeOH)₂) dissolved in 100 mM KCl aqueous solution.

- Nanohole Fabrication Material: A 100 nm thin gold film supported on a glass substrate.

Procedure

- Nanofabrication: Fabricate an array of nanoholes in the gold film using a Focused Ion Beam (FIB). Typical nanohole dimensions are 100 nm in depth and 75-100 nm in diameter, creating an attoliter-scale measurement volume [30].

- Optical Setup:

- Employ a Total Internal Reflection (TIR) illumination setup. Illuminate the glass-gold interface with a laser to generate an evanescent field that penetrates into the nanoholes without directly illuminating the bulk solution.

- Use a high-numerical-aperture objective to collect the scattered light from the nanoholes [30].

- Electro-Optical Measurement:

- Connect the gold film as the working electrode in a standard potentiostat setup.

- Apply a cyclic voltammetry potential sweep (e.g., from -0.2 V to 0.2 V) to the nanohole electrode while simultaneously recording the optical scattering signal.

- Use a lock-in amplifier synchronized to a small potential modulation to significantly enhance the signal-to-noise ratio and detect minute optical changes caused by the electrochemical processes [30].

- Data Analysis:

- The optical scattering intensity is linked to the local ion concentration within the nanohole. Compare the experimentally measured optical signal with theoretical predictions from a Poisson-Nernst-Planck-Butler-Volmer (PNP-BV) model.

- The correlation between the optical contrast and the modeled ion concentration provides a direct, label-free readout of the electrochemical reaction dynamics and EDL (dis)charging within the nanoconfined space [30].

Visualization of EDL Structure and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: This visualization illustrates the structure of the Electrical Double Layer (EDL) at a positively charged electrode. The Stern Layer contains specifically adsorbed ions and water molecules. The Diffuse Layer consists of a cloud of mobile cations and anions, the distribution of which is governed by a balance between electrostatic attraction and thermal motion. The structure and dynamics of this entire interface control electrochemical reactivity [38] [36].

Diagram 2: This workflow outlines the key steps in a protocol to investigate the EDL and its effects on redox reactions using cyclic voltammetry. The process involves meticulous electrode preparation, surface modification, electrochemical measurement, and data analysis to extract parameters that reveal the properties of the interface [37] [9].

Practical CV Methods and Applications in Drug Development and Research

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a powerful and ubiquitous electrochemical technique used to study redox reaction mechanisms, providing both qualitative and quantitative information about electrochemical systems [39]. In pharmaceutical and diagnostic research, CV enables the investigation of electron transfer processes crucial for understanding drug metabolism, biomarker detection, and biosensor development [40]. This technique involves sweeping the working electrode potential linearly with time between specified limits while measuring the resulting current, generating a characteristic "duck-shaped" plot known as a voltammogram [9]. The resulting current-potential data reveals crucial electrochemical parameters including formal potentials, electron transfer kinetics, diffusion coefficients, and reaction mechanisms [11]. This application note provides a standardized protocol for researchers establishing CV methodologies for redox reaction analysis, with particular emphasis on proper electrolyte preparation, instrument configuration, and measurement execution to ensure reproducible and meaningful results.

Theoretical Principles and Key Parameters

Fundamental Electrochemical Theory

In CV, a three-electrode system subjects the electrochemical cell to a linearly cycled potential sweep while measuring the current response [9]. For a reversible redox couple, the peak current (ip) is described by the Randles-Ševčík equation at 25°C:

[i_p = (2.69 \times 10^5) \cdot n^{3/2} \cdot A \cdot D^{1/2} \cdot C \cdot v^{1/2}]

where n is the number of electrons transferred, A is the electrode area (cm²), D is the diffusion coefficient (cm²/s), C is the concentration (mol/cm³), and v is the scan rate (V/s) [9]. The peak potential separation (ΔEp = Epa - Epc) for a reversible, one-electron transfer process is approximately 59 mV at 25°C, with equal anodic and cathodic peak currents (ipa/ipc = 1) [11]. Reversibility requires fast electron transfer kinetics sufficient to maintain Nernstian equilibrium conditions throughout the potential scan [11].

Criteria for Electrochemical Reversibility

Electrochemical reversibility depends on the relative values of the standard heterogeneous electron transfer rate constant (ks) and the scan rate (v) [11]. A system exhibits reversible behavior when ks/v is sufficiently large to maintain Nernstian surface concentrations. Quasi-reversible systems show ΔEp > 59/n mV, with values increasing with scan rate, while irreversible systems display shifted peak potentials and diminished reverse peaks [11]. Chemical reactions coupled to electron transfer, such as acid-base reactions or decomposition processes, can also cause irreversibility by altering the redox species during the potential cycle [41].

Table 1: Diagnostic Parameters for Reversible Redox Systems in Cyclic Voltammetry

| Parameter | Reversible System Criteria | Experimental Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Potential Separation (ΔEp) | 59.2/n mV at 25°C | Indicates thermodynamic reversibility and number of electrons transferred |

| Peak Current Ratio (ipa/ipc) | 1 at all scan rates | Confirms stability of redox species during potential cycle |

| Peak Current Function (ip/v¹/²) | Independent of scan rate | Validates diffusion-controlled process |

| Peak Potential | Independent of scan rate | Suggests fast electron transfer kinetics |

Materials and Reagent Preparation

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Cyclic Voltammetry Experiments

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | KCl, PBS (0.1-1.0 M) | Provides ionic conductivity, controls ionic strength |

| Redox Probe | Potassium ferricyanide, Ferrocene, [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺ | Generates faradaic current for redox process characterization |

| Solvent | Acetonitrile, Aqueous buffers | Dissolves electrolyte and redox species |

| Working Electrode | Glassy carbon, Gold, Platinum | Surface for redox reactions to occur |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl, SCE | Provides stable potential reference |

| Counter Electrode | Platinum wire, Graphite rod | Completes electrical circuit without reaction interference |

| Purification Gas | Nitrogen, Argon | Removes dissolved oxygen from solution |

Electrolyte and Redox Probe Selection

The choice of electrolyte composition significantly impacts redox reactivity and electron transfer kinetics [42] [40]. Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) provides pH stabilization but may yield lower sensitivity compared to potassium chloride (KCl) at equivalent ionic strengths [40]. For the ferro/ferricyanide system ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻), increased electrolyte ionic strength shifts the RC semicircle in Nyquist plots to higher frequencies, enhancing signal response [40]. However, [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ exhibits surface-sensitive behavior on carbon electrodes and may show quasi-reversible kinetics, while [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺ behaves as a more ideal outer-sphere redox probe but at higher cost [43]. Optimal signal-to-noise ratios for low-cost analyzers can be achieved using buffered electrolytes like PBS with high ionic strength and lowered redox probe concentrations [40].

Experimental Setup and Protocols

Electrolyte Preparation Protocol

Solution Preparation: Prepare supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl or PBS) using high-purity water (resistivity ≥18 MΩ·cm). Accurately weigh electrolyte salts using analytical balance and dissolve in appropriate solvent volume [43].

Redox Probe Addition: Add redox-active species to electrolyte solution. Typical concentrations range from 1-5 mM for routine characterization. For ferricyanide, prepare 5 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆] in 0.1 M KCl [43].

Oxygen Removal: Sparge solution with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes before measurements to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with redox processes [44].

pH Adjustment: Adjust pH using dilute acid/base solutions as needed. For PBS, maintain pH 7.4 for biological applications [40].

Electrode Preparation and Cell Assembly

Working Electrode Polishing: Polish glassy carbon electrode sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm alumina slurry on microcloth pads. Rinse thoroughly with purified water between polishing steps [44].

Electrode Cleaning: Sonicate electrode in appropriate solvent (water, ethanol) for 2-5 minutes to remove residual polishing material [44].

Cell Assembly: Insert clean, dry electrodes into cell ports, ensuring proper orientation and immersion depth. Connect electrodes to potentiostat following manufacturer's configuration [45].

Solution Transfer: Transfer deoxygenated electrolyte solution to electrochemical cell, ensuring electrodes are fully immersed. Maintain inert atmosphere during measurement if needed [44].

Potentiostat Configuration and Measurement

Instrument Warm-up: Switch on potentiostat at least 30 minutes before measurements to ensure thermal stability and accurate readings [44].

Open Circuit Potential Measurement: Measure open circuit potential (Eoc) to establish baseline potential before applying controlled potentials [45].

Parameter Settings: Configure CV parameters based on experimental requirements:

- Initial potential: Typically 100-200 mV before expected E⁰'

- Vertex potentials: Set to encompass redox events of interest

- Scan rate: 10-100 mV/s for initial characterization

- Number of cycles: 2-5 cycles to ensure reproducibility [45]

Current Range Selection: Select appropriate current range based on expected response. Use autoranging if available, or estimate using Randles-Ševčík equation [45].

Experiment Execution: Initiate measurement sequence, monitoring real-time voltammogram display for anomalies. Save data in appropriate format for subsequent analysis [39].

Cyclic Voltammetry Experimental Workflow

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Voltammogram Analysis Protocol

Peak Identification: Identify anodic (Epa) and cathodic (Epc) peak potentials and corresponding currents (ipa, ipc) from the voltammogram [11].

Reversibility Assessment: Calculate ΔEp = Epa - Epc and ipa/ipc ratio. Compare to theoretical values for reversible systems (ΔEp = 59/n mV, ipa/ipc = 1) [11].

Formal Potential Determination: Calculate formal potential E⁰' = (Epa + Epc)/2 for reversible systems [11].

Scan Rate Studies: Perform CV at multiple scan rates (e.g., 10-1000 mV/s). Plot ip vs. v¹/² to verify linear relationship expected for diffusion-controlled processes [9].

Electroactive Area Calculation: Using the Randles-Ševčík equation with known concentration and diffusion coefficient, calculate electroactive area from slope of ip vs. v¹/² plot [9].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Cyclic Voltammetry Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Large ΔEp (>59/n mV) | Slow electron transfer kinetics, Uncompensated resistance | Decrease scan rate, Check electrode connections, Use supporting electrolyte |

| Asymmetric peak currents | Chemical reactivity of redox species, Adsorption phenomena | Verify redox species stability, Clean electrode surface |

| High background current | Contaminated electrode, Electrolyte impurities | Repolish electrode, Use higher purity reagents |

| Non-reproducible peaks | Unstable reference electrode, Drifting open circuit potential | Condition reference electrode, Ensure stable temperature |

| No faradaic peaks | Incorrect potential window, Degraded redox species | Verify redox couple E⁰', Prepare fresh solutions |

Advanced Applications in Research