Beyond the Background: Advanced Strategies for Correcting Non-Faradaic Currents in Biomedical Electroanalysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing non-Faradaic (capacitive) currents, a major source of interference in electrochemical biosensing.

Beyond the Background: Advanced Strategies for Correcting Non-Faradaic Currents in Biomedical Electroanalysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing non-Faradaic (capacitive) currents, a major source of interference in electrochemical biosensing. Covering foundational principles to cutting-edge applications, we explore the critical distinction between Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes and their impact on assay sensitivity in complex matrices like serum and blood. The content details innovative hardware and methodological solutions, including differential potentiostats and specialized measurement techniques, for real-time background suppression. It further offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for electrode design and system validation, culminating in a comparative analysis of techniques to enhance the accuracy, reliability, and translational potential of electrochemical diagnostics and bioanalytical assays.

Understanding the Signal and the Noise: A Primer on Non-Faradaic Currents in Bioelectrochemistry

Fundamental Definitions

What is the core difference between a Faradaic and a non-Faradaic process?

A Faradaic process involves the transfer of charge (electrons) across the electrode-electrolyte interface, leading to oxidation or reduction reactions. In contrast, a non-Faradaic process involves the storage of charge at the interface without any electron transfer or change in the oxidation state of species [1] [2].

- Faradaic Process (Charge Transfer): This is an electron transfer reaction where ions in the electrolyte gain or lose electrons at the electrode surface. Examples include ions interacting directly with the electrode or molecules undergoing redox reactions. This process produces a faradaic current that is easily identified in techniques like cyclic voltammetry as distinct peaks [1].

- Non-Faradaic Process (Charge Storage): This process does not involve electron transfer reactions. Instead, charge is stored electrostatically through mechanisms like ion adsorption onto the electrode surface or intercalation into materials without changing their oxidation state. This generates a capacitive current, characterized by a rectangular shape in cyclic voltammetry, indicating simple charging and discharging [1] [2].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics:

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Faradaic and Non-Faradaic Processes

| Feature | Faradaic Process | Non-Faradaic Process |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Transfer | Yes, across the electrode interface | No, charge is stored at the interface |

| Redox Reactions | Occurs; oxidation states change | Does not occur; no change in oxidation state |

| Current Type | Faradaic current | Capacitive (non-faradaic) current |

| Cyclic Voltammetry Signature | Peaks representing redox reactions | Rectangular shape representing charging/discharging |

| Process Reversibility | Often chemically irreversible | Highly electrically reversible |

| Primary Mechanism | Electron transfer (oxidation/reduction) | Electrostatic attraction, ion adsorption, double-layer formation |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Identifying Process Type

How can I tell if my measurement is dominated by a Faradaic or non-Faradaic signal?

You can distinguish them by analyzing your cyclic voltammetry (CV) data [1]:

- Faradaic Signal: Look for distinct, sharp peaks in the voltammogram. The position of these peaks corresponds to the redox potential of the electroactive species.

- Non-Faradaic Signal: Look for a rectangular, box-like shape in the voltammogram. This indicates a continuous charging and discharging of the electrical double-layer.

It is crucial to note that broad peaks in a CV do not automatically confirm a Faradaic process, as some capacitive materials can also exhibit such features [2].

Why is the capacitive (non-faradaic) current considered a key limitation in sensitive electrochemical assays?

The non-faradaic current acts as a significant, non-zero background signal. This is particularly problematic in modern assay systems, such as those using DNA monolayers, because it can [3]:

- Overwhelm the smaller faradaic current from the analyte of interest.

- Limit the signal-to-noise ratio, reducing assay sensitivity.

- Saturate the instrument's amplifiers, especially when using larger electrode surfaces to amplify the faradaic signal.

FAQ: Mitigating Non-Faradaic Current

What experimental strategies can I use to suppress non-faradaic current interference?

Several methodological and hardware approaches can be employed:

- Hardware Subtraction: Using a differential potentiostat (DiffStat) with two working electrodes. One electrode (W1) provides the analytical signal (faradaic + non-faradaic), while the other (W2) provides only the background (non-faradaic). The DiffStat subtracts the background from the analytical signal in real-time, outputting a signal predominantly composed of faradaic current [3].

- Pulsed Voltammetry Techniques: Using techniques like square-wave voltammetry (SWV) or differential pulse voltammetry, which can digitally subtract background currents during data processing [3].

- Control Electrode Surface Area: Since non-faradaic current is directly proportional to electrode surface area, reducing the area can lower the background. However, this also reduces the faradaic current, requiring more sensitive instrumentation [3].

My droplet-based electrochemical measurements (e.g., SECCM) show abnormally high activity at grain boundaries. Is this a Faradaic enhancement?

Not necessarily. Studies on polycrystalline platinum have shown that surface tension effects at grain boundaries can have a large conflating effect in droplet-based techniques like Scanning Electrochemical Cell Microscopy (SECCM), often producing false positives. The local curvature and wettability of the surface can alter the meniscus contact and the measured current, which may be mistaken for enhanced Faradaic (electrocatalytic) activity. Rigorous surface preparation and surface area correction techniques are required to confirm true intrinsic activity [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Differentiating Processes via Cyclic Voltammetry

This protocol provides a methodology to characterize an electrode material and identify the nature of its electrochemical response.

- 1. Objective: To distinguish between Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

- 2. Materials:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- Standard three-electrode cell

- Working Electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, gold, or material under study)

- Counter Electrode (e.g., platinum wire)

- Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl)

- Electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.5 M H₂SO₄ or other suitable supporting electrolyte)

- 3. Methodology:

- Prepare the electrode surface according to standard procedures (e.g., polishing for solid electrodes).

- Set up the electrochemical cell with the working, counter, and reference electrodes immersed in the electrolyte.

- Program the potentiostat with a CV method. A typical initial scan would be from -0.2 V to +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl and back, at a scan rate of 50 mV/s.

- Run the CV and record the current response.

- Analyze the resulting voltammogram for the presence of peaks (indicative of Faradaic processes) or a rectangular shape (indicative of non-Faradaic, capacitive behavior) [1] [2].

- 4. Data Interpretation:

- Identify and note the number of peaks, their potential positions (Epa for anodic, Epc for cathodic), and their peak currents (ip).

- A large, rectangular current with no distinct peaks suggests the material is primarily capacitive.

Protocol 2: Hardware Suppression of Non-Faradaic Current

This protocol outlines the use of a differential potentiostat to minimize capacitive background in sensitive measurements, such as DNA-based hybridization assays [3].

- 1. Objective: To suppress non-faradaic current in real-time using a differential potentiostat (DiffStat) configuration.

- 2. Materials:

- Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat)

- Two electrochemical cells, each with a separate Working Electrode (W1 and W2)

- Split Reference Electrode and Counter Electrode to connect both cells

- For DNA sensing: Gold working electrodes functionalized with thiolated DNA monolayers.

- 3. Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Fabricate W1 and W2 in two separate cells to prevent cross-contamination. The analyte (e.g., MB-DNA) is added only to W1. A carefully matched control (e.g., CTR-DNA) is added to W2 to ensure the non-faradaic components are identical [3].

- Instrument Setup: Connect W1 and W2 to the DiffStat's two working electrode inputs. The DiffStat utilizes matching transimpedance amplifier circuits for each electrode, with the outputs fed into a differential instrumentation amplifier for real-time analog subtraction [3].

- Measurement: Perform the electrochemical measurement (e.g., Chronoamperometry, CV, or SWV). The DiffStat will output a signal where the background capacitive current from W2 has been subtracted from the combined signal from W1.

- 4. Data Interpretation: Compare the output from the DiffStat with data from a conventional potentiostat. A successful implementation will show a significant reduction in the baseline current while preserving the faradaic peak current.

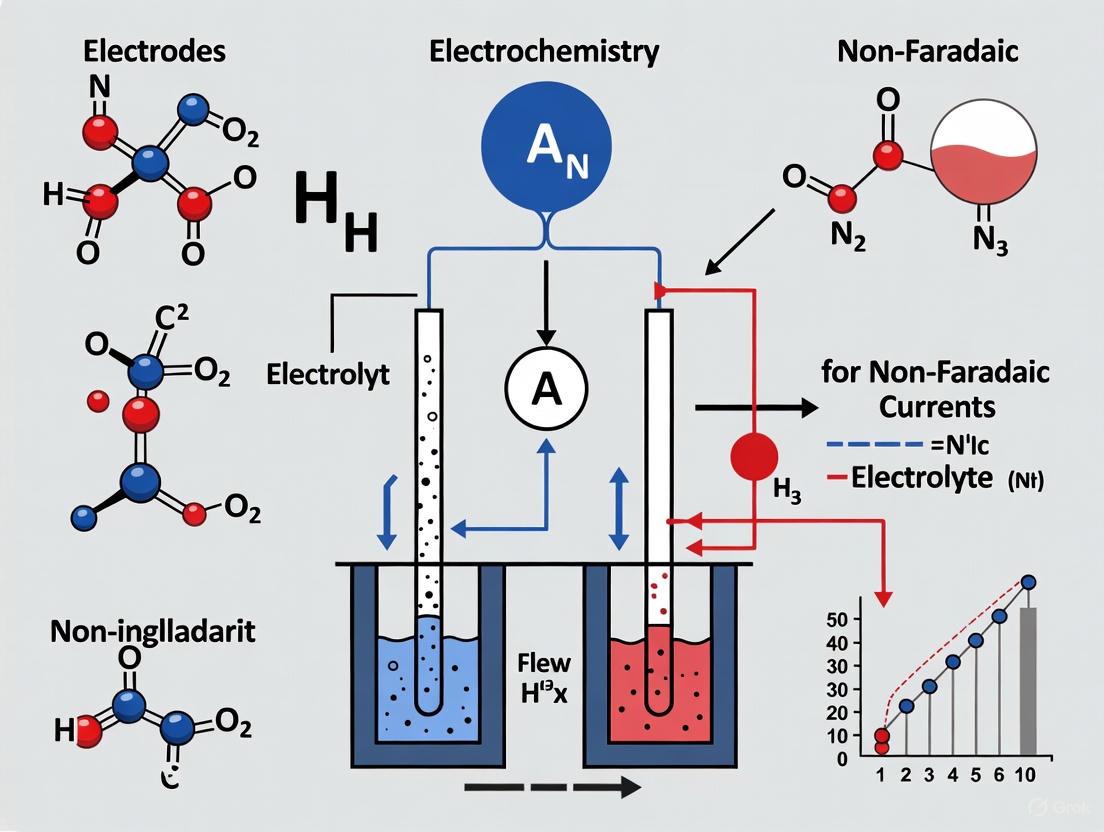

Visual Explanations

Diagram 1: Process Comparison and Measurement Setup

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Their Functions in Electrochemical Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Bismuth Electrode | An environmentally friendly alternative to mercury electrodes for sensitive tensiometric and electrochemical measurements [5]. |

| Quasi-Reference Counter Electrode (QRCE) | Integrated into nanopipette probes for techniques like SECCM, providing a compact reference and counter electrode system [4]. |

| Nanopipette Probe | A borosilicate glass pipette with a nanoscale tip (e.g., 200 nm) used in SECCM to isolate and measure tiny areas of an electrocatalyst surface [4]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | A common redox reporter molecule used in DNA-based electrochemical assays (e.g., E-DNA biosensors) to generate a faradaic current [3]. |

| Thiolated DNA | Used to form self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold electrodes, which serve as the foundation for many modern bioanalytical sensors [3]. |

| Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) | Specialized hardware that uses two working electrodes to perform real-time analog subtraction of non-faradaic background current [3]. |

Theoretical Foundations: The Electrical Double Layer

What is the electrical double layer and how does it form?

The electrical double layer (EDL) is a structure that forms at the interface between an electrode and an electrolyte solution when the two are brought into contact [6]. This interface is fundamental to all electrochemical systems. When a charged electrode is introduced into an electrolyte, the electric field generated by the electrode surface acts on the charged ions in the solution, causing them to rearrange [7]. This results in a structured region of ions that screens the electrode's charge from the bulk solution.

The formation follows this sequence:

- The electrode possesses a surface charge (either positive or negative).

- Ions of opposite charge (counter-ions) in the solution are electrostatically attracted to the electrode surface.

- Ions of the same charge (co-ions) are repelled from the surface.

- This rearrangement creates a "double layer" of charge: one layer on the electrode surface and a second layer of ions in the solution.

What are the key models describing the EDL structure?

Our understanding of the EDL has evolved through several key historical models, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Electrical Double Layer Models

| Model | Key Proposer(s) | Year(s) | Core Concept | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helmholtz | Hermann von Helmholtz | 1853 | A rigid, molecular capacitor with two layers of opposite charge [6] [8]. | Does not consider thermal motion of ions; only valid for high electrolyte concentrations [6]. |

| Gouy-Chapman | Gouy & Chapman | 1910, 1913 | A diffuse layer where ion distribution is governed by electrostatic forces and thermal motion [6] [8]. | Predicts impossibly high ion densities near the electrode for high potentials [6]. |

| Stern | Otto Stern | 1924 | A hybrid model: a rigid Stern layer of adsorbed ions and a diffuse Gouy-Chapman layer [6] [8]. | Treats ions as point charges; assumes constant permittivity [6]. |

| Grahame | D.C. Grahame | 1947 | Divided the Stern layer into the Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP) (specifically adsorbed, desolvated ions) and the Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP) (solvated ions at their closest approach) [6]. | - |

| Bockris/Devanathan/Müller (BDM) | Bockris, Devanathan, & Müller | 1963 | Incorporated the specific orientation of solvent molecules (e.g., water) at the electrode surface, which influences the interface's permittivity [6]. | - |

The following diagram illustrates the structure of the electrical double layer, integrating concepts from the Stern, Grahame, and BDM models.

Diagram 1: Structure of the Electrical Double Layer and Potential Decay

What is the direct link between the EDL and non-Faradaic current?

The non-Faradaic current (also called charging or capacitive current) originates directly from the capacitor-like nature of the electrical double layer [9] [10].

- The Double Layer as a Capacitor: The electrode-electrolyte interface behaves like a capacitor, often termed the double-layer capacitance (Cdl). The charged electrode and the layer of counter-ions in the solution act as the two "plates" of this capacitor, separated by a molecular-scale distance [9] [8].

- Charging Current: When the potential applied to the electrode is changed, the charge stored on this "capacitor" must also change. The current that flows to effect this change in charge—by rearranging ions at the interface—is the non-Faradaic current [10]. It is described by the equation:

i_c = C_dl * (dE/dt)wherei_cis the capacitive current,C_dlis the double-layer capacitance, anddE/dtis the rate of change of the applied potential [9] [11]. - Key Characteristic: In a purely non-Faradaic process, no electrons transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface to cause oxidation or reduction of solution species. The charge transfer is purely electrostatic [9] [2].

Table 2: Contrasting Faradaic and Non-Faradaic Processes

| Feature | Faradaic Process | Non-Faradaic (Capacitive) Process |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Electron transfer across the interface causes oxidation/reduction reactions [9]. | Electrostatic charging/discharging of the double-layer capacitor; no redox chemistry [9] [2]. |

| Governed by | Faraday's Law (amount of chemical change ∝ current) [9]. | Capacitance law (q = C×E) [10]. |

| Current Type | Faradaic current. | Charging (capacitive) current. |

| Effect on Solution | Composition changes (Ox Red). | No net change in solution composition; only ion rearrangement at the interface. |

| Persistence | Continuous current at constant potential (if mass transport is sustained). | Transient current only when potential is changing (dE/dt ≠ 0) [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

How can I minimize the interference of non-Faradaic current in my measurements?

Non-Faradaic current is a major source of background interference, limiting the sensitivity and detection limit of electrochemical assays, particularly those using DNA monolayers or other surface-bound systems [3]. The table below outlines common problems and solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Non-Faradaic Current Interference

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solutions & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| High background in cyclic voltammetry (CV) or square-wave voltammetry (SWV) | Large C_dl and fast scan rates (dE/dt) leading to large i_c [3] [10]. |

1. Use pulsed techniques (e.g., SWV, differential pulse voltammetry) which discriminate against capacitive current [3]. 2. Reduce scan rate to lower i_c (but this also lowers faradaic signal). 3. Employ background subtraction in software or, ideally, via hardware (see Section 2.2). |

| Low signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio in chronoamperometry | Non-faradaic decay current obscures the faradaic response [3]. | 1. Use a longer delay time before current measurement to allow capacitive decay. 2. Apply data fitting to model and subtract the decaying background [3]. |

| Instrument amplifier saturation | Using a large electrode surface area, which increases both faradaic and non-faradaic currents [3]. | 1. Reduce working electrode area (but this also reduces desired faradaic signal). 2. Implement hardware current subtraction (e.g., a differential potentiostat) to remove the capacitive component before amplification [3]. |

| Difficulty detecting low analyte concentrations | Faradaic signal is small and obscured by the capacitive background [3]. | 1. Optimize electrochemical technique parameters (pulse height, step potential, frequency). 2. Lower the measurement's time constant to better resolve faradaic and non-faradaic components. 3. Use a differential potentiostat (DiffStat) for real-time analog suppression of capacitive current [3]. |

What advanced hardware solutions exist for non-Faradaic current suppression?

A powerful approach is the use of a differential potentiostat (DiffStat), which suppresses non-faradaic current through real-time analog subtraction [3].

- Concept: The DiffStat uses two working electrodes (W1 and W2) in a single electrochemical cell.

- W1 is the functional sensor (e.g., with a DNA monolayer and redox reporter).

- W2 is a nearly identical "blank" electrode (e.g., with a DNA monolayer but no redox reporter).

- How It Works: Since both electrodes have the same double-layer structure, they experience nearly identical non-faradaic currents. The DiffStat circuitry measures the current at both electrodes simultaneously and subtracts the background current (from W2) from the total current (from W1) in real-time [3]. The output is a signal predominantly composed of faradaic current.

- Benefits:

- Improved S/N Ratio: Can suppress capacitive background by ~5-fold or more [3].

- Larger Accessible Electrodes: Prevents amplifier saturation, allowing the use of larger electrodes for bigger faradaic signals.

- Simplified Data Processing: Outputs a "cleaner" signal, reducing the need for complex digital background fitting [3].

The workflow and configuration of a DiffStat are illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Comparison of Conventional and Differential Potentiostat Configurations

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

How do I characterize the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) of my electrode material?

Objective: To determine the double-layer capacitance, a key parameter defining the magnitude of non-faradaic current, for a modified or unmodified electrode.

Principle: In a potential window where no faradaic reactions occur, the electrode-electrolyte interface behaves like a pure capacitor. By measuring the current response to different potential scan rates in this "non-faradaic" region, Cdl can be calculated.

Materials & Equipment:

- Potentiostat (standard three-electrode system)

- Working Electrode (material under study)

- Counter Electrode (e.g., Pt wire)

- Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl)

- Electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M KCl or other supporting electrolyte without redox-active species)

Procedure:

- Setup: Place the working electrode in the electrolyte solution and connect the three-electrode system to the potentiostat.

- Select a Non-Faradaic Potential Window: Using cyclic voltammetry (CV), identify a potential range (e.g., ±50 mV around the open circuit potential) where no redox peaks are observed. This confirms the absence of faradaic processes.

- Record CVs at Multiple Scan Rates: In this selected potential window, record CV scans at several different scan rates (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 mV/s).

- Measure Charging Current: For each scan rate, measure the current (

i_c) at a fixed potential within the window (e.g., at the middle of the potential range). - Plot and Calculate: Plot the absolute value of the charging current (

|i_c|) against the scan rate (v). The relationship should be linear:i_c = C_dl * v. The double-layer capacitance (Cdl) is the slope of this line.

Notes:

- For a flat electrode, Cdl is often reported in

F/cm². Ensure you know the precise geometric area of your electrode. - For porous or high-surface-area materials, the measured value is the total capacitance, which can be used to estimate the electroactive surface area (ECSA).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Investigating and Managing Non-Faradaic Effects

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, NaNO₃, KPF₆) | Carries current in solution without participating in faradaic reactions. High concentration minimizes solution resistance and defines the Debye length (double-layer thickness) [7]. | Used in all electrochemical experiments to control ionic strength and minimize IR drop. |

| Redox-Inactive Probe Molecules | Molecules that do not undergo electron transfer in the studied potential window. Used to characterize the capacitive properties of the interface without faradaic interference. | Used in the CV scan-rate method to determine Cdl (Protocol 3.1). |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Forming Thiols (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) | Forms an organized, dense monolayer on gold electrodes. This passivates the surface and drastically reduces Cdl by moving the diffuse layer further from the electrode [3]. | Used in E-DNA and E-AB biosensors to minimize non-faradaic background and prevent nonspecific adsorption [3]. |

| Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) | Specialized hardware that uses two working electrodes for real-time analog subtraction of capacitive current [3]. | For high-sensitivity measurements in complex matrices (e.g., serum, whole blood) where background currents are high and unstable [3]. |

| Redox Reporters with Large ∆Ep (e.g., Methylene Blue) | Molecules with a significant potential difference between oxidation and reduction peaks. This allows analytical techniques (like SWV) to be performed at potentials away from the large current swings of the redox event, reducing overlap with capacitive currents [3]. | Used as labels in DNA-based electrochemical sensors to generate a measurable faradaic signal [3]. |

Why Non-Faradaic Currents Limit Sensitivity and Accuracy in Biomedical Sensing

FAQ: What are Non-Faradaic Currents and Why are They Problematic?

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a Faradaic and a non-Faradaic process? A Faradaic process involves the actual transfer of charged particles (electrons) across the electrode-electrolyte interface, leading to a reduction-oxidation (redox) reaction. After applying a constant current, the electrode charge, voltage, and composition reach constant values [2]. In contrast, a non-Faradaic process (also called capacitive) does not involve charge transfer across the interface; instead, charge is progressively stored at the electrode surface, much like a capacitor charging and discharging [12] [2]. This charging of the electrical double layer at the interface is the source of non-Faradaic, or capacitive, current [3].

Q2: How exactly do non-Faradaic currents interfere with sensor measurements? Non-Faradaic currents act as a significant, non-zero baseline interference that obscures the desired analytical signal—the Faradaic current [3]. This interference has several direct consequences:

- Reduced Signal-to-Background Ratio: The capacitive current can overwhelm the smaller Faradaic current generated by the target biomarker, making the signal difficult to distinguish from noise [3].

- Limited Electrode Surface Area: The magnitude of the non-faradaic current is directly proportional to the electrode surface area. Using larger electrodes to amplify the Faradaic signal simultaneously amplifies the background capacitive current, which can saturate the instrument's amplifiers and limit detection sensitivity [3].

- Narrowed Detection Range: The large background can compress the dynamic range of the sensor, limiting its ability to detect a wide concentration of analytes [3].

TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE: Mitigating Non-Faradaic Currents

Problem: My electrochemical biosensor has a high background signal, limiting its detection sensitivity. Solution: Here are proven strategies to suppress non-Faradaic interference:

- Solution 1: Implement Hardware Subtraction. Utilize a differential potentiostat (DiffStat). This instrument uses two working electrodes: one experimental sensor (W1) and one "blank" background electrode (W2). The circuitry performs real-time, analog subtraction of the capacitive current from W2 from the total current from W1, outputting a signal that is predominantly the desired Faradaic current. This method has been shown to suppress capacitance current by approximately 5-fold in chronoamperometry measurements [3].

- Solution 2: Optimize Electrode Geometry and Material. For capacitive (non-Faradaic) biosensors, the design of interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) is critical. Research shows that reducing the gap between the fingers of the IDE significantly enhances sensitivity. One study found that a 3 μm gap configuration could detect a target concentration of 50 ng/mL, a threshold unattainable by designs with 4 μm or 5 μm gaps [13]. Furthermore, be aware that electrode material stability impacts performance. Aluminum electrodes, for instance, are susceptible to surface corrosion in extreme pH environments, which degrades their performance in both Faradaic and non-Faradaic measurements [14].

- Solution 3: Leverage Underutilized Impedimetric Parameters. When using a non-Faradaic EIS biosensor, do not rely solely on measuring capacitance. A study on interleukin-8 (IL-8) detection demonstrated that the imaginary impedance (Zimag) parameter provided the best performance, with a limit of detection of 90 pg/mL and the highest sensitivity at 13.1 kΩ/log(ng/mL), outperforming the more commonly measured capacitance [15].

Experimental Protocols for Advanced Research

Protocol 1: Differentiating Faradaic and Non-Faradaic Processes via Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) This protocol helps characterize the nature of your electrode process.

- 1. Objective: To determine whether an electrode material exhibits primarily Faradaic or non-Faradaic behavior.

- 2. Materials:

- Potentiostat

- Standard three-electrode setup (Working, Counter, Reference electrodes)

- Electrode material under test

- Electrolyte solution (e.g., PBS or with a redox couple like [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻)

- 3. Methodology:

- Prepare the electrode and place it in the electrolyte solution.

- Run a cyclic voltammetry scan at a moderate scan rate (e.g., 50 mV/s) over a suitable potential window.

- Observe the shape of the CV curve.

- 4. Data Interpretation:

- Faradaic Dominated: Look for distinct, sharp oxidation and reduction peaks corresponding to redox reactions [2].

- Non-Faradaic Dominated: The CV diagram will have a more rectangular, box-like shape, characteristic of capacitive charging and discharging. Note that broad peaks can sometimes appear in capacitive materials, so shape alone is not definitive; the underlying charge storage mechanism is key [2].

Protocol 2: Detecting a Biomarker using a Non-Faradaic Impedimetric Biosensor This protocol outlines the steps for a label-free capacitive biosensor, optimized for an interdigitated electrode (IDE).

- 1. Objective: To functionalize an IDE and detect a specific biomarker (e.g., IL-8) by monitoring changes in non-Faradaic impedance parameters [15].

- 2. Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gold Interdigitated Electrodes (Au-IDEs) | The transducer platform; its surface is modified to capture the target. |

| Cysteamine | Forms a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on the gold surface, providing terminal amine groups for further cross-linking [15]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A crosslinker that reacts with the amine groups from cysteamine, providing aldehyde groups for antibody immobilization [15]. |

| IL-8 Antibodies | The biorecognition element that selectively binds to the IL-8 antigen target [15]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used to block non-specific binding sites on the electrode surface, reducing false-positive signals [15]. |

| Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides a stable ionic environment for electrochemical measurements [15]. |

- 3. Methodology:

- Biofunctionalization:

- SAM Formation: Incubate the clean Au-IDE in a 1 mM ethanolic cysteamine solution for 1 hour. Rinse with ethanol and dry with N₂ [15].

- Cross-linking: Apply 50 μL of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS to the surface. Incubate for 1 hour. Rinse with DI water and dry with N₂ [15].

- Antibody Immobilization: Apply 50 μL of a 1 μg/mL IL-8 antibody solution. Incubate for 1 hour. Rinse with DI water [15].

- Surface Blocking: Apply 50 μL of 5% BSA in PBS. Incubate for 30 minutes. Rinse with DI water and dry with N₂ [15].

- Non-Faradaic EIS Measurement:

- Baseline: Place 50 μL of PBS on the functionalized IDE. Measure the open-circuit potential (OCP) for 100 seconds to ensure equilibrium [15].

- Acquisition: Conduct EIS measurements with a zero DC potential (relative to OCP) to operate in a non-Faradaic mode. A small AC voltage (e.g., 10 mV) is applied across a frequency range (e.g., 100 Hz to 1 MHz) [15].

- Detection: Replace PBS with the sample solution containing the IL-8 antigen. Repeat the EIS measurement.

- Biofunctionalization:

- 4. Data Analysis:

- Extract key impedance parameters from the spectra: Imaginary Impedance (Zimag), Impedance Magnitude (Zmod), Capacitance, and Real Impedance (Zreal).

- Construct a calibration curve by plotting the change in the parameter (e.g., Zimag) against the logarithm of the antigen concentration. As per recent findings, Zimag is likely to provide the highest sensitivity and lowest limit of detection [15].

Performance Data of Mitigation Strategies

The table below summarizes quantitative data from recent studies on improving sensor performance by addressing non-Faradaic currents.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Different Strategies for Managing Non-Faradaic Effects

| Strategy | Experimental Context | Key Performance Metric | Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Subtraction (DiffStat) | DNA monolayer-based sensor using Chronoamperometry (CA) | Capacitive Current Suppression | ~5-fold reduction | [3] |

| Electrode Geometry Optimization | IDE biosensor for antibody detection | Limit of Detection (LoD) | 3 μm gap: 50 ng/mL (Lowest achievable) | [13] |

| Parameter Selection (Non-Faradaic EIS) | Au-IDE biosensor for IL-8 detection | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Zimag: 90 pg/mL; Capacitance: 140 pg/mL | [15] |

| Parameter Selection (Non-Faradaic EIS) | Au-IDE biosensor for IL-8 detection | Sensitivity | Zimag: 13.1 kΩ/log(ng/mL) (Highest) | [15] |

Technological Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: Fundamental processes and the problem of non-Faradaic current.

Diagram 2: DiffStat workflow for hardware-level current suppression.

Troubleshooting Guide: Improving Signal-to-Background Ratios

Problem: High non-faradaic (capacitive) background currents are obscuring my analytical signal.

Non-faradaic or capacitive current originates from the formation of a double layer at the electrode and monolayer surface, creating a time-dependent background that interferes with the analytical faradaic current. This is a key factor limiting sensitivity in many electrochemical assays, especially those based on DNA monolayers [3].

Solutions:

- Implement a Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat): This hardware solution uses two working electrodes (W1 for signal, W2 for background) with matching transimpedance amplifier circuits that feed into a differential instrumentation amplifier. The signals from both electrodes are collected simultaneously and analog-subtracted, effectively suppressing the capacitive current at the source [3]. This method has been shown to suppress baseline capacitance current by approximately 5-fold in chronoamperometry and can make larger electrodes and higher sensitivity settings accessible [3].

- Optimize Electrochemical Techniques: Use pulse voltammetry techniques like Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV), which are designed to discriminate against capacitive currents through digital subtraction during data processing [3].

- Control Electrode Surface Area: Since non-faradaic current is directly proportional to electrode surface area, consider using smaller electrodes. Be aware that this will also reduce your faradaic current, requiring higher sensitivity instrumentation [3].

- Refine Data Processing: Apply digital background subtraction or fitting algorithms to chronoamperometric data during analysis to remove the non-faradaic component [3].

Problem: My signal is lost in environmental and instrumental noise.

Environmental electrical interference is a pervasive source of artifacts, often manifesting as 50/60 Hz mains hum or high-frequency hash.

Solutions:

- Use Differential Amplification: Employ a differential amplifier with a high Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR > 100 dB). This setup measures the voltage difference between an active electrode and a reference electrode, subtracting noise common to both inputs (like line noise) [16].

- Establish Proper Grounding and Shielding:

- Single-Point Grounding: Connect all components to a single common earth ground point to prevent ground loops, a major source of 60 Hz hum [16].

- Faraday Cage: Use a conductive enclosure around the experimental preparation and headstage to attenuate high-frequency electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI) [16].

- Cable Management: Use shielded, twisted-pair cables and avoid running power and signal lines in parallel to minimize inductive and capacitive coupling [16].

- Apply Digital Filtering (Post-Acquisition):

- Notch Filter: Precisely remove 50/60 Hz mains interference. Use cautiously as it can introduce artifacts [16].

- Low-Pass Filter: Attenuate high-frequency noise (e.g., thermal noise). Set the cutoff just above the fastest frequency component of your biological signal [16].

- High-Pass Filter: Remove slow baseline drift caused by electrode instability or temperature changes [16].

- Use Signal Averaging: For signals time-locked to a stimulus (e.g., evoked potentials), repeatedly record and average the responses. Uncorrelated random noise averages toward zero, while the time-locked signal is enhanced, improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) proportionally to the square root of the number of trials [17] [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does electrode surface area affect my signal and background, and what are the trade-offs?

The electrode surface area has a direct and often competing impact on both faradaic (signal) and non-faradaic (background) currents.

- Faradaic Current: The analytical signal from your redox reaction is generally proportional to the electrode surface area. A larger area provides more reaction sites, increasing your signal [18].

- Non-Faradaic (Capacitive) Current: This background current is also directly proportional to the electrode surface area. A larger electrode creates a larger double-layer capacitance, leading to a higher background [3].

The key trade-off is that while increasing surface area boosts your signal, it can boost the background even more, potentially worsening the signal-to-background ratio. Furthermore, the total current (signal + background) may saturate your instrument's amplifiers if the electrode is too large, limiting usable electrode size and ultimate detection sensitivity [3].

Q2: What is amplifier saturation, and how can I prevent it?

Amplifier saturation (or clipping) occurs when the amplified signal exceeds the maximum input voltage range of your analog-to-digital converter (ADC). This causes irreversible distortion and loss of high-amplitude signal features [16]. In the context of an LNA, as it nears saturation, its gain reduces, weakening the signal of interest and increasing intermodulation products [19].

Prevention Strategies:

- Adjust Gain Settings: Reduce the amplifier's gain to ensure the output voltage does not exceed the ADC's input range [16].

- Use a Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat): By subtracting the capacitive background in hardware, the DiffStat outputs a signal that is predominantly faradaic current, preventing the large background from consuming the available dynamic range and causing saturation [3].

- Check Electrode Surface Area: If using a conventional potentiostat, a large electrode surface area can generate currents that are too high for the instrument's amplifiers. Using a smaller electrode may be necessary [3].

Q3: My electrode impedance is high. How will this impact my data quality?

High electrode impedance can meaningfully reduce data quality by increasing low-frequency noise, which decreases the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [20]. This is primarily because impedance imbalances between electrodes degrade the amplifier's common-mode rejection capability, making the system more susceptible to environmental noise [16] [20]. The consequence is that you will need to average more trials to achieve the same level of statistical significance in your averaged data, as the SNR of an average increases only with the square root of the number of trials [20].

Q4: Can I fix a signal-to-background problem solely through data analysis?

While digital background subtraction and filtering during data analysis can be effective, it is not the only or always the best solution. A key limitation of digital subtraction is that the large background currents remain in the raw data, which can still saturate instrument amplifiers and limit the use of larger, higher-signal electrodes [3]. Hardware-based solutions, like the differential potentiostat, subtract the background in real-time at the analog level, circumventing this limitation and often simplifying subsequent data processing [3].

Experimental Protocol: Suppressing Non-Faradaic Current with a DiffStat

This protocol outlines the methodology for using a differential potentiostat to suppress capacitive currents in a DNA-based hybridization assay, as described in the research [3].

Objective: To measure faradaic current from a methylene blue (MB)-tagged DNA target while suppressing the non-faradaic background.

Materials:

- Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) [3]

- Two electrochemical cells, each with a Gold working electrode (W1 & W2)

- Split reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) and split counter electrode

- Thiolated DNA probe for self-assembled monolayers (SAM) on gold

- Target DNA sequence conjugated with Methylene Blue (MB-DNA)

- Control DNA sequence without the redox reporter (CTR-DNA)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Create DNA monolayers by immobilizing the thiolated DNA probe onto the gold working electrodes W1 and W2.

- Solution Addition:

- To the cell containing working electrode W1, add the MB-DNA target solution. This electrode will produce both faradaic and non-faradaic currents.

- To the cell containing working electrode W2, add the CTR-DNA control solution. This electrode, lacking the redox reporter, will produce only the non-faradaic background current.

- Electrochemical Connection: Connect the two cells using the split reference and counter electrodes to complete the electrochemical circuit while preventing cross-contamination.

- DiffStat Measurement: Run your chosen electrochemical technique (e.g., Chronoamperometry, Square-Wave Voltammetry). The DiffStat will simultaneously measure the current from W1 and W2 and output the analog-subtracted signal (W1 - W2), which is predominantly the faradaic current.

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from the evaluation of a differential potentiostat (DiffStat) for background suppression [3].

| Parameter | Conventional Potentiostat | Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Capacitive Current | Baseline level = 1 (reference) | ~5-fold suppression | Chronoamperometry (CA) |

| Accessible Electrode Size | Limited by amplifier saturation | Enables use of larger electrodes | N/A |

| Sensitivity Setting | Limited by high background | Enables higher sensitivity settings | N/A |

| Data Processing | Requires complex digital subtraction | Simplifies extraction of faradaic current | Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) | Core hardware for real-time, analog subtraction of non-faradaic background currents using two working electrodes [3]. |

| Gold Electrodes | Standard substrate for forming well-organized DNA self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) used in many modern bioassays [3]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | A common redox reporter molecule; its electron transfer efficiency can be optimized to improve the faradaic signal [3]. |

| Thiolated DNA Probes | Anchor onto gold electrodes to create a stable, functional sensing interface (e.g., for E-DNA or E-AB biosensors) [3]. |

| Control DNA (No Reporter) | Essential for the background (W2) electrode in a DiffStat setup to provide a matched non-faradaic current for subtraction [3]. |

Logical Workflow: Conventional vs. Differential Potentiostat Configurations

Troubleshooting Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Problems

Practical Strategies for Suppression: From Hardware Innovation to Measurement Techniques

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using a DiffStat over a conventional potentiostat? The DiffStat provides order-of-magnitude improvements in sensitivity by suppressing non-Faradaic (capacitive) background currents through real-time analog subtraction. This allows the use of larger electrode surfaces and higher instrument sensitivity settings, which are often inaccessible with standard potentiostats due to amplifier saturation from high background currents [3].

Q2: My differential measurement shows an unstable baseline. What could be the cause? Unstable baselines are frequently caused by mismatched electrode surfaces or inconsistent monolayer coverage between the two working electrodes (W1 and W2). Ensure that both electrodes are prepared simultaneously using identical protocols for gold cleaning and DNA monolayer formation to guarantee equivalent capacitive backgrounds [3].

Q3: Can the DiffStat be used for "signal-off" assays? Yes, the DiffStat can uniquely convert traditional "signal-off" assays into "signal-on" formats. By configuring one electrode (W1) as the active sensor and the second (W2) with a non-responsive background, the differential output directly reports a positive signal upon analyte binding, simplifying data interpretation [3].

Q4: How does the DiffStat perform in complex biological matrices like serum? The differential measurement capability of the DiffStat enables effective background drift correction even in challenging environments like 50% human serum. The real-time subtraction compensates for drifting baselines caused by matrix effects, enhancing assay robustness [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Excessive Noise in Differential Output

Symptoms: The differential signal is noisy, obscuring the faradaic response.

- Check 1: Verify the integrity of all physical connections to the two working electrodes, reference electrode, and counter electrode. Loose connections introduce significant noise.

- Check 2: Ensure both working electrodes (W1 and W2) are in separate electrochemical cells but share a common reference and counter electrode through a split configuration to prevent cross-contamination [3].

- Check 3: Confirm that the DNA monolayer coverages on W1 and W2 are nearly identical. Significant differences in surface properties lead to imperfect background subtraction.

Problem: Poor Suppression of Capacitive Current

Symptoms: The differential output still shows a significant sloping baseline in techniques like SWV.

- Check 1: The composition of the background solution in the W2 cell must be meticulously matched to the analytical solution in the W1 cell, including matching the ionic strength and the type and concentration of the DNA control sequence (e.g., CTR-DNA) [3].

- Check 2: The surface area of W1 and W2 must be as identical as possible. Even small differences in electrode geometry will result in residual uncompensated capacitive current.

Problem: Saturated Output Signal

Symptoms: The potentiostat's output is at its maximum voltage limit.

- Check 1: Reduce the gain or sensitivity setting on the DiffStat instrument. The much lower background current often allows for higher gain settings than with a ConStat, but the limit may be reached with very large electrodes.

- Check 2: If using a large surface area electrode, try a smaller one to reduce the absolute current magnitude, both faradaic and non-faradaic.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experiment: Validation of Non-Faradaic Current Suppression

Objective: To demonstrate the effectiveness of the DiffStat in suppressing non-Faradaic current across different electrochemical techniques [3].

Methodology:

- Sensor Fabrication: Prepare two gold working electrodes (W1, W2) with thiolated DNA monolayers.

- Analyte Introduction: Introduce methylene-blue-tagged DNA (MB-DNA) target to the W1 cell and a control DNA (CTR-DNA) to the W2 cell.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Perform Chronoamperometry (CA), Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), and Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) measurements simultaneously with a conventional potentiostat (ConStat) and the DiffStat for comparison.

- Data Analysis: Compare the magnitude of the non-faradaic background and the signal-to-background ratio between the two instruments.

Key Results:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ConStat vs. DiffStat [3]

| Electrochemical Technique | Non-Faradaic Current Suppression (DiffStat) | Signal-to-Background Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| Chronoamperometry (CA) | ~5-fold suppression of capacitive current | Significant increase |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Significant suppression observed | Notable improvement |

| Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Background essentially reduced to zero | Dramatic improvement; simplifies data processing |

Workflow: DiffStat Operation for a DNA Hybridization Assay

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the core signaling principle of the differential potentiostat.

Protocol: Implementing Real-Time Background Correction in Serum

Objective: To leverage the DiffStat for continuous background drift correction in a complex matrix (50% human serum) [3].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Setup: Configure W1 as the biosensor electrode and W2 as a background electrode with a similar, non-specific DNA monolayer.

- Baseline Acquisition: Immerse both electrodes in 50% human serum and record a stable baseline using the DiffStat.

- Analyte Addition: Spit the target analyte into the solution containing W1.

- Continuous Monitoring: Record the differential output over time. The DiffStat will subtract the drifting background signal (common to both W1 and W2 in the serum matrix) from the specific faradaic signal generated at W1.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for DiffStat Experiments [3]

| Item | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Gold Disk Electrodes | Serve as the platform for forming self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) and the DNA-based sensor interface. |

| Thiolated DNA Probes | Form the self-assembled monolayer on the gold electrode; provide the specific recognition element for the target. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | A redox reporter molecule that is appended to DNA; generates the faradaic current measured in the assay. |

| Control DNA (CTR-DNA) | A non-redox-labeled DNA sequence used in the background electrode (W2) to match the chemical environment of W1. |

| Six-Chloride Iridium | Used as a split reference electrode, providing a stable and reproducible reference potential for both working electrodes. |

| Human Serum | A complex biological matrix used to validate assay performance and background correction in a clinically relevant medium. |

Fundamental Concepts: Why Use Dual Working Electrodes?

What is the primary advantage of using a dual working electrode system for background referencing?

The primary advantage is the significant suppression of non-Faradaic current, also known as capacitive or charging current. This current originates from the formation of an electrical double layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface and acts as a major interference background in electrochemical measurements. Unlike digital subtraction performed during data analysis, a dual-electrode system performs real-time analog subtraction of this background within the potentiostat hardware itself, leading to cleaner data and improved sensitivity [3].

How does the differential potentiostat (DiffStat) configuration work?

A conventional potentiostat uses a single working electrode. In contrast, a differential potentiostat (DiffStat) utilizes a cell with two working electrodes (W1 and W2) [3]. Both electrodes are connected to matching current-to-voltage converter circuits. The signals from W1 (the experimental sensor) and W2 (the background reference) are collected simultaneously and fed into an on-board differential instrumentation amplifier, which performs continuous, analog subtraction of the W2 signal from the W1 signal. This process outputs a signal where the shared non-Faradaic background is greatly reduced, leaving a predominantly faradaic current [3].

The following diagram illustrates the signal flow and subtraction process in a DiffStat.

Experimental Protocols & Setups

Core Methodology: DNA Monolayer-Based Sensor

A validated application of this technology is for nucleic acid hybridization assays using DNA monolayers on gold electrodes [3].

- Sensor Design: A thiolated DNA probe is immobilized on a gold working electrode (W1) to form a self-assembled monolayer. The target is a complementary DNA strand labeled with a redox reporter, such as Methylene Blue (MB).

- Reference Electrode Design: The second working electrode (W2) is prepared identically but is exposed to a non-redox-active control DNA sequence (CTR-DNA). This ensures the non-faradaic background at both electrodes is nearly identical.

- Measurement: When the MB-DNA target hybridizes with the probe on W1, a faradaic current from the MB reporter is generated. The DiffStat subtracts the nearly identical capacitive background from W2, leaving a clean, background-suppressed faradaic signal from the hybridization event [3].

Electrode Configuration and Cell Setup

To prevent cross-contamination between the sensor and reference electrodes, it is recommended to fabricate W1 and W2 in two separate electrochemical cells. A split reference electrode and counter electrode can then be used to establish electrochemical contact with both cells simultaneously [3].

The table below summarizes the key techniques and their performance with a DiffStat.

Table 1: Performance of Differential Potentiostat Across Electrochemical Techniques

| Technique | Key Improvement with DiffStat | Observed Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Chronoamperometry (CA) | Suppression of capacitance current in the baseline. | ~5-fold suppression of non-faradaic current was observed [3]. |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Removal of the non-zero baseline. | Enables clearer visualization of faradaic peaks [3]. |

| Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Direct output of a background-subtracted signal. | Greatly simplifies data processing; non-faradaic current is suppressed "essentially to zero" [3]. |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

We observe excessive noise or signal drift after implementing the dual-electrode setup. What could be the cause?

- Mismatched Electrodes: The fundamental requirement for effective subtraction is that the non-faradaic background at W1 and W2 must be nearly identical. Ensure the two working electrodes are fabricated from the same material, have the same geometry and surface area, and are modified with the same monolayer chemistry and coverage.

- Reference Electrode Instability: A drifting reference electrode potential will skew the applied potential at both working electrodes, causing apparent signal drift. Test your reference electrode against a stable master reference electrode by measuring the open-circuit potential between them; a difference of >5 mV indicates a problem [21]. Always store reference electrodes in their proper filling solution to prevent crystallization and potential drift [21].

- Configuration Limitations: Be aware that using a two-electrode configuration (where one electrode acts as both reference and counter) or configurations where the counter electrode is a similar size to the working electrode can distort the electrochemical response and become the rate-limiting step. For benchtop validation, a standard three-electrode configuration with a large counter electrode is recommended [22].

Our faradaic signal is still low after background subtraction. How can we improve sensitivity?

The DiffStat's key benefit is enabling the use of larger electrode surface areas without amplifier saturation from high capacitive currents. Since faradaic current is also proportional to surface area, you can increase the surface area of your working electrodes to boost the absolute faradaic signal. The DiffStat will simultaneously handle the corresponding increase in non-faradaic current, which would otherwise be prohibitive on a standard potentiostat [3].

Can this system convert a "signal-off" assay into a "signal-on" assay?

Yes, this is a unique application. In a traditional signal-off assay, the binding of a target causes a decrease in signal. With a DiffStat, you can configure the system so that this decrease at W1 is subtracted from a stable background at W2, resulting in a net negative differential signal. By inverting this output, the assay is converted to a more intuitive signal-on format [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Dual-WE Experiments

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) | Instrument that performs real-time analog subtraction of signals from two working electrodes. | Can be constructed from open-source designs [3]. |

| Paired Working Electrodes | The sensor (W1) and reference (W2) electrodes. Must be matched. | Gold disk electrodes; DNA-modified gold surfaces [3]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for the electrochemical cell. | Ag/AgCl (e.g., in saturated KCl) [21] [23]. |

| Master Reference Electrode | A pristine reference electrode used solely to validate the stability of other reference electrodes. | A dedicated Ag/AgCl electrode stored in KCl solution [21]. |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit, often made from inert material. | Platinum wire or mesh [22] [23]. |

| Redox Reporter | Molecule that undergoes faradaic reaction, generating the analytical signal. | Methylene Blue (MB) [3]. |

| Surface Passivation Monolayer | Forms a well-defined interface on the electrode, reducing non-specific binding. | Thiolated DNA or alkanethiol self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold [3]. |

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps for setting up and running a successful experiment with dual working electrodes.

A fundamental challenge in electrochemical analysis is distinguishing the faradaic current, which arises from electron transfer in redox reactions, from the non-faradaic (capacitive) current, which originates from the charging and discharging of the electrical double layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface [24]. Non-faradaic currents act as a significant background interference, compromising assay sensitivity, limiting usable electrode surface area, and narrowing the detection range [3]. This technical brief provides troubleshooting guidance and methodologies for researchers to effectively suppress these capacitive currents, thereby enhancing the reliability of their electrochemical measurements.

Core Concepts & Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between Faradaic and Non-Faradaic currents?

- Faradaic Current: This is the current from actual redox reactions where electrons are transferred across the electrode-electrolyte interface, leading to chemical transformations. It is the analytical signal of interest that directly relates to the concentration of the analyte [24].

- Non-Faradaic Current (Capacitive Current): This current comes from the rearrangement of ions at the electrode surface to form an electrical double layer. No electron transfer occurs across the interface, and it does not cause a chemical change. It manifests as a time-dependent background signal that can obscure faradaic responses [3] [24].

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally identify if my signal is compromised by capacitive current?

Examine the raw output from techniques like chronoamperometry (CA) or square-wave voltammetry (SWV). A large, decaying transient in CA or a pronounced, sloping baseline in SWV that lacks the characteristic peak shape of a faradaic process strongly indicates significant capacitive interference [3].

FAQ 3: My data is noisy with a high background at larger electrode surfaces. What is the cause and solution?

Cause: The magnitude of the non-faradaic current is directly proportional to the electrode surface area (SA). Using larger electrodes to increase faradaic signal also amplifies the capacitive background, which can saturate instrument amplifiers and increase noise [3]. Solution: Consider a Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) configuration. This hardware uses two working electrodes to subtract the capacitive background in real-time via analog circuitry, allowing the use of larger SAs and higher sensitivity settings without amplifier saturation [3].

Advanced Methodology: The Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat)

The DiffStat represents a hardware-level solution for non-faradaic current suppression. Its configuration and operation principle are as follows:

DiffStat Configuration and Workflow

Experimental Protocol for DiffStat Validation

This protocol outlines a hybridization-based DNA sensor assay to demonstrate the efficacy of the DiffStat in suppressing non-faradaic current [3].

1. Electrode and Cell Preparation:

- Working Electrodes (W1 & W2): Use two separate gold disk electrodes. Clean and polish them to a mirror finish. W1 and W2 must be fabricated in two separate electrochemical cells to prevent cross-contamination.

- Reference and Counter Electrodes: Employ a split reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) and a split counter electrode (e.g., Pt wire) to establish electrochemical contact with both cells simultaneously.

- DNA Monolayer Formation: Immerse both W1 and W2 in a solution of thiolated DNA probes to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on each gold surface.

2. Analyte and Control Introduction:

- Working Electrode 1 (W1 - Signal): Introduce the target analyte, which is a complementary DNA strand labeled with a redox reporter (e.g., Methylene Blue, MB). This creates the MB-DNA complex, generating both faradaic and non-faradaic currents.

- Working Electrode 2 (W2 - Background): Introduce a control DNA sequence that is identical but lacks the Methylene Blue label (CTR-DNA). This carefully matches the non-faradaic components of W1 but provides no faradaic signal.

3. Electrochemical Measurement:

- Connect the prepared electrochemical cells to the DiffStat.

- Perform simultaneous measurements on W1 and W2 using Chronoamperometry (CA), Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), or Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV).

- The DiffStat's internal differential amplifier performs real-time analog subtraction of W2's signal from W1's signal.

Performance Data and Analysis

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Conventional vs. Differential Potentiostat

| Parameter | Conventional Potentiostat | Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitive Current Suppression | Baseline level | ~5-fold suppression in Chronoamperometry [3] | 5x |

| Faradaic Current | Unchanged | Unchanged [3] | - |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio | Limited by high background | Order-of-magnitude improvements [3] | >10x |

| Electrode Surface Area Use | Limited by amplifier saturation | Enables use of larger electrodes [3] | Expanded range |

| Data Processing for SWV | Requires complex digital subtraction | Simplified extraction of faradaic current [3] | Major simplification |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for DNA-Based Electrochemical Assays

| Item | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Disk Electrodes | Provides a stable, inert surface for forming DNA monolayers via gold-thiol chemistry. | Standard working electrode for DNA-based sensors [3]. |

| Thiolated DNA Probes | DNA strands with a thiol group at one terminus for covalent attachment to gold surfaces, forming the sensing monolayer. | Foundation for E-DNA, E-AB, and ECPA biosensors [3]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | A redox reporter molecule that can be appended to DNA. Its electron transfer generates the faradaic current. | Redox label in hybridization-based DNA sensors [3]. |

| Split Reference Electrode | A shared reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) with separate connections to maintain identical potential in both cells of a DiffStat setup. | Critical for the dual-cell DiffStat configuration [3]. |

Application Note: Converting Signal-OFF to Signal-ON Assays

A unique application of the DiffStat is its ability to convert traditional "signal-off" assays into more intuitive "signal-on" assays [3]. In a typical signal-off E-DNA sensor, target binding causes a decrease in the faradaic SWV peak. With the DiffStat:

- W1 is configured as the functional signal-off sensor.

- W2 is configured as a static, non-responsive DNA monolayer.

- When the target binds to W1, its signal decreases. The DiffStat subtracts the constant signal from W2, resulting in a differential output that increases as the signal from W1 decreases. This effectively converts the signal-off response into a signal-on output, which can be easier to interpret and quantify.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of converting a signal-OFF assay to a signal-ON format? Converting a signal-OFF assay to a signal-ON format provides a direct, proportional relationship between the target analyte concentration and the reported signal. This significantly improves the assay's sensitivity and ease of interpretation, circumventing the inherent limitations of signal-OFF assays where signal suppression has a maximum limit of 100%, which can hinder detection of low analyte concentrations and make naked-eye observation difficult [25].

Q2: How does a differential potentiostat (DiffStat) correct for signal drift in complex samples like human serum? The DiffStat uses two working electrodes (W1 and W2) measured simultaneously. The background current (non-faradaic and drift components) from a "blank" electrode (W2) is subtracted in real-time via analog circuitry from the signal of the experimental electrode (W1). This hardware-level subtraction actively removes the background signal and its drift, which is crucial for accurate measurements in complex, variable matrices like 50% human serum [3].

Q3: Why is non-faradaic current a significant problem in electrochemical biosensors? Non-faradaic, or capacitive, current acts as a large, fluctuating background signal that can obscure the smaller faradaic current generated by the redox reaction of the reporter molecule. This high background limits the signal-to-noise ratio, narrows the detection range, and can saturate the instrument's amplifiers, thereby restricting the sensitivity and overall performance of the biosensor [3].

Q4: Can I use standard screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) with the DiffStat for on-site testing? The DiffStat configuration requires two working electrodes. While the cited research used custom-fabricated electrodes in separate cells to prevent cross-contamination, the principle is compatible with any two-electrode setup. For portability, a specially designed screen-printed electrode array that incorporates two working electrodes, a shared reference, and a shared counter electrode would be ideal and is a logical extension of this technology [3] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Background Noise and Capacitive Current Overwhelming Faradaic Signal

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Excessive electrode surface area leading to large capacitive currents.

- Solution: The DiffStat hardware is specifically designed to suppress this. If using a conventional potentiostat, you must reduce the electrode surface area, though this also reduces the faradaic signal. The DiffStat allows the use of larger electrodes for a stronger signal without the background penalty [3].

- Cause: Mismatched self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) or probe coverages on the two working electrodes (W1 and W2) in a DiffStat setup.

- Solution: Ensure that the fabrication of W1 and W2 is performed in parallel using identical protocols, solutions, and incubation times to guarantee that the non-faradaic background is nearly identical on both electrodes, enabling effective subtraction [3].

- Cause: Inadequate matching of the redox reporter and its control.

- Solution: When using a methylene blue (MB)-labeled DNA probe on W1, use an identical DNA sequence without the MB label on W2 (control electrode). This carefully matches the non-faradaic components between the two electrodes [3].

Problem 2: Successful Signal-OFF to Signal-ON Conversion but Poor Sensitivity

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient displacement of the signaling probe in a competitive assay format.

- Cause: Suboptimal performance of the signaling element (e.g., nanozyme).

- Solution: If using a nanozyme (e.g., PVP-capped Pt nanocubes), ensure it is properly synthesized and that its activity is modulated effectively, for instance, with metal ions like Ag⁺, to achieve maximum catalytic signal amplification [25].

Problem 3: Signal Drift in Complex Biological Samples (e.g., Serum)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Non-specific adsorption of proteins or other matrix components onto the electrode surface.

- Solution: Employ a well-formed and dense self-assembled monolayer (SAM) to passivate the electrode surface. The DiffStat configuration provides continuous correction for this type of drift, as the non-specific adsorption will occur on both W1 and W2 and be subtracted out [3].

- Cause: Chemical or electrochemical fouling of the electrode.

- Solution: Use the DiffStat's real-time differential measurement for continuous background correction. This hardware approach circumvents the need for complex digital post-processing and provides stable baseline correction even in 50% human serum [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Converting a Signal-OFF DNA Hybridization Assay to Signal-ON Using a DiffStat

This protocol details the use of a differential potentiostat to transform a traditional signal-off sensor into a signal-on format [3].

1. Principle In a standard signal-off assay, target binding reduces the faradaic signal. The DiffStat uses two working electrodes: the experimental electrode (W1) with a signaling probe (e.g., MB-DNA), and a control electrode (W2) with a non-signaling probe (CTR-DNA). The analog subtraction of W2's signal from W1's signal cancels the common non-faradaic background. The faradaic signal from MB on W1 remains, converting a signal-off event on a single electrode (loss of MB signal) into a signal-on event in the differential readout (the background-subtracted signal is dominated by the faradaic current) [3].

2. Materials

- Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat): Custom-built hardware with two working electrode inputs and an onboard differential instrumentation amplifier [3].

- Working Electrodes (W1 & W2): Two gold electrodes fabricated in separate electrochemical cells to prevent cross-contamination.

- Reference and Counter Electrodes: A split reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) and counter electrode (e.g., Pt wire) for electrochemical contact with both cells.

- Probe Solutions:

- Thiolated DNA capture probe.

- Methylene Blue-labeled DNA target (MB-DNA) for W1.

- Identical, unlabeled DNA target (CTR-DNA) for W2.

- Buffer: Appropriate phosphate buffer or hybridization buffer.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

| Step | Action | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Electrode Preparation: Clean the gold working electrodes (W1 and W2) according to standard protocols (e.g., piranha treatment, electrochemical cycling). | Ensure identical surface roughness and cleanliness for both W1 and W2. |

| 2. | SAM Formation: Immobilize the thiolated DNA capture probe onto both W1 and W2 electrodes via self-assembly. | Use the same batch of probe solution and incubation time (often 1-24 hours) to achieve matched monolayer coverages. |

| 3. | Probe Introduction: To the cell containing W1, add the MB-DNA signaling probe. To the cell containing W2, add the CTR-DNA control probe. | The concentrations and sequences of MB-DNA and CTR-DNA must be identical except for the redox label. |

| 4. | Hybridization: Allow the labeled targets to hybridize with the surface-bound capture probes. | |

| 5. | DiffStat Measurement: Connect W1, W2, the reference, and counter electrodes to the DiffStat. Run the desired electrochemical technique (e.g., Square-Wave Voltammetry). | The DiffStat performs real-time analog subtraction of the W2 signal from the W1 signal. |

| 6. | Target Introduction (Signal-ON Readout): Introduce the unlabeled target analyte (e.g., complementary DNA). The analyte displaces the MB-DNA from W1, reducing its faradaic current, while the non-faradaic background on both electrodes remains matched. The differential output (W1 - W2) will show a net increase as the non-faradaic background is stripped away, revealing the signal-on response. |

4. Expected Results With a conventional potentiostat, target binding would cause a decrease in the MB faradaic peak (signal-OFF). With the DiffStat, the same binding event produces a differential signal where the background is effectively zero, and the displacement of MB leads to an apparent signal-ON response due to the removal of the suppressed background, simplifying data interpretation and improving the signal-to-noise ratio [3].

Protocol 2: Real-Time Background Drift Correction in 50% Human Serum

This protocol leverages the DiffStat for continuous measurement in complex biological fluids without complex data processing [3].

1. Principle The non-faradaic current and signal drift caused by matrix effects in human serum are similar on two identically prepared working electrodes. The DiffStat's synchronous measurement and analog subtraction of the signal from W2 (background electrode) from W1 (sensing electrode) removes these common-mode interferences in real-time, providing a stable baseline.

2. Materials

- Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat): As in Protocol 1.

- Electrodes: Same two-electrode setup as in Protocol 1.

- Biological Matrix: 50% human serum in an appropriate buffer.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

| Step | Action | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sensor Preparation: Prepare the W1 and W2 electrodes identically, as described in Protocol 1, Steps 1-4. | The key is perfect matching of the two electrodes to ensure serum-induced drifts are identical. |

| 2. | Baseline in Buffer: Place a clean, blank buffer solution in both electrochemical cells. Record a baseline measurement with the DiffStat. | The differential signal should be a stable, flat line close to zero. |

| 3. | Introduction of Serum: Replace the buffer in both cells with 50% human serum. | Ensure both cells receive serum from the same stock solution at the same time. |

| 4. | Continuous Monitoring: Observe the differential output (W1 - W2) over time. The drift caused by the serum matrix will be subtracted, resulting in a stable baseline, allowing for accurate subsequent measurement of the target analyte. | This setup corrects for both non-faradaic charging current and low-frequency signal drift. |

4. Expected Results The DiffStat will output a significantly more stable baseline in 50% human serum compared to a conventional potentiostat. This stability allows for the direct and continuous monitoring of analyte binding without the need for digital background subtraction or frequent recalibration, facilitating adaptation to point-of-care testing [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials used in the advanced applications discussed.

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) | Core instrument that performs real-time analog subtraction of non-faradaic currents using two working electrodes [3]. |

| Methylene Blue (MB)-labeled DNA | Redox reporter molecule used as a signaling probe on the experimental working electrode (W1) [3]. |

| Unlabeled Control DNA (CTR-DNA) | Control probe, identical to the signaling probe but without the redox label, used on the background electrode (W2) to match non-faradaic components [3]. |

| Thiolated DNA Capture Probe | Forms a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on gold electrodes, providing a well-defined surface for probe immobilization and hybridization [3]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Used as electron-transfer mediators; can attach to captured bacteria to provide an electrical pathway across an insulating SAM, enhancing signal in impedimetric sensors [28]. |

| Pt-based Nanozymes (e.g., PVP-PtNC) | Artificial enzyme mimics with peroxidase-like activity; used in colorimetric assays to replace natural enzymes, offering higher stability and catalytic activity for signal amplification [25]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) Array | Provides a portable, disposable platform for electrochemical detection; can be designed with multiple working electrodes for differential measurements [26]. |

Visualized Workflows

Diagram 1: DiffStat Signal Conversion Logic

Diagram 2: Experimental Setup for Serum Drift Correction

Optimizing Assay Performance and Troubleshooting Common Pitfalls

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How can I reduce high non-Faradaic (capacitive) background currents that are interfering with the measurement of my faradaic signal?

- Issue: High capacitive background currents can overwhelm the analytical faradaic current, limiting signal-to-noise ratios and detection sensitivity, especially in complex matrices like serum or blood [3].

- Solution:

- Hardware Subtraction: Implement a differential potentiostat (DiffStat). This setup uses two working electrodes: one experimental (W1) and one as a background reference (W2). The circuitry performs real-time analog subtraction of the capacitive current from W2, outputting a signal predominantly composed of the faradaic current from W1 [3].

- Electrode Pretreatment: Perform electrochemical pretreatment cycles to reinforce the passivation layer on the electrode surface. This can help prevent electrolyte penetration and subsequent Faradaic side reactions that contribute to background and self-discharge [29].

- Optimize Electrode Area: While reducing the working electrode surface area can decrease capacitive current, it also reduces the faradaic signal. A DiffStat allows the use of larger electrodes without amplifier saturation, providing a better solution [3].

FAQ 2: My electrodeposited catalyst film is uneven. Which parameter is most critical to ensure uniform deposition?

- Issue: Uneven catalyst distribution on the substrate, often due to nucleation problems [30].

- Solution: