Advanced Strategies for Preventing Electrode Fouling in Redox Systems: From Mechanisms to Biomedical Applications

Electrode fouling and passivation present critical challenges that compromise the sensitivity, stability, and longevity of electrochemical systems used in biomedical research and drug development.

Advanced Strategies for Preventing Electrode Fouling in Redox Systems: From Mechanisms to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

Electrode fouling and passivation present critical challenges that compromise the sensitivity, stability, and longevity of electrochemical systems used in biomedical research and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of fouling mechanisms in complex biofluids, explores cutting-edge antifouling materials and electrode designs, and outlines robust methodological and operational strategies for performance preservation. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with applied troubleshooting and validation protocols, this resource equips researchers with a systematic framework to enhance the reliability of electrochemical diagnostics and biosensing in clinical and pharmaceutical settings.

Understanding Electrode Fouling: Fundamental Mechanisms and Impacts in Biomedical Redox Systems

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between electrode fouling and passivation?

A1: Fouling and passivation are distinct degradation processes that reduce electrode performance.

- Fouling is the accumulation of contaminants (e.g., organic matter, precipitated solids) on the electrode surface. This physical layer decreases the electrode's active surface area, increases electrical resistance, and hinders mass transfer of reactants [1].

- Passivation is the loss of electroactivity due to the formation of a chemically bound oxide or hydroxide layer (e.g., aluminium oxide on an aluminium electrode). This passive layer minimizes the electrode's effective surface area for redox reactions and increases electrical resistance, thereby reducing the production of essential coagulants or charge transfer [1] [2].

Q2: What are the primary causes of these phenomena in electrochemical systems?

A2: The causes can be system-specific, but general drivers include:

| Phenomenon | Primary Causes |

|---|---|

| Fouling | High levels of Natural Organic Matter (NOM) and salinity in the water source; high contaminant load; adsorption of contaminants onto the electrode surface [1]. |

| Passivation | Formation of oxide layers from secondary reactions between the electrode material, water, and oxygen; deposition of metal ions; and accumulation of organic matter that contributes to a passive layer [1] [2]. |

Q3: Why is it critical to distinguish between fouling and passivation for troubleshooting?

A3: Accurate diagnosis is essential because mitigation strategies differ. Applying a solution for fouling to a passivated electrode (or vice versa) will be ineffective.

- Addressing fouling typically involves strategies to reduce contaminant deposition, such as pre-treatment or optimizing hydrodynamics.

- Addressing passivation requires methods to prevent or remove the oxide layer, such as controlling applied current or introducing aggressive ions that suppress film formation [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Electrode Surface Issues

Objective: Systematically identify whether an electrode performance loss is due to fouling, passivation, or a combination of both.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| A soft, easily removable layer of organic or particulate matter on the electrode surface. | Fouling | Implement pre-treatment (e.g., filtration) to reduce contaminant load. Analyze floc composition with EDX to identify foulants [1]. |

| A hard, chemically bound layer that is difficult to remove mechanically. | Passivation | Perform Tafel plot analysis to assess the electrode's electrochemical activity and the presence of a passive oxide layer [1]. |

| Gradual increase in system electrical resistance and overpotential during operation. | Fouling or Passivation | Combine characterization techniques: use EDX for surface composition (fouling) and Tafel analysis for electrochemical activity (passivation) [1] [2]. |

| Reduced production of metal hydroxide coagulants in an electrocoagulation system. | Passivation | Optimize electric current/voltage to prevent faradaic losses and check for oxide layer formation on the aluminium electrode [1]. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Fouling and Passivation

Objective: Apply targeted strategies to prevent or reduce the impact of fouling and passivation.

| Strategy | Target Phenomenon | Methodology & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Pre-Treatment & Design | Both | Use perforated electrodes or proper configuration (spacing, surface area) to enhance mass transfer and reduce stagnant zones where fouling/passivation can initiate [1]. |

| Operational Parameter Control | Both | Control applied electric current and voltage to prevent faradaic losses and minimize conditions that accelerate oxide layer formation or contaminant adhesion [1]. |

| Chemical Environment Adjustment | Passivation | Introduce a controlled mixture of seawater or other sources of aggressive ions (e.g., chloride) which can compete with oxide formation and help suppress the development of passive film layers [1]. |

| Conductive Polymer Coatings | Passivation/Fouling | Apply coatings like poly(pyrrole)/PSS or PEDOT/PSS on carbonaceous electrodes. These can improve reaction selectivity, act as a redox shuttle, and physically inhibit passivation or contaminant adhesion [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterization

Protocol 1: Tafel Plot Analysis for Passivation Assessment

Objective: Quantify electrochemical kinetics and identify the presence of a passive layer on the electrode surface.

Principle: The Tafel plot elucidates the relationship between the electrochemical reaction rate (current density) and the overpotential. A shift in the Tafel slope can indicate the presence of a passivating layer affecting charge transfer [1].

Materials:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- Standard three-electrode cell (Working electrode: sample under test; Counter electrode: e.g., platinum wire; Reference electrode: e.g., Saturated Calomel Electrode)

- Relevant electrolyte solution

Procedure:

- Cell Setup: Prepare the three-electrode cell with the electrode of interest as the working electrode, immersed in the appropriate electrolyte.

- Open Circuit Potential (OCP): Measure the OCP to establish a stable baseline potential.

- Potentiodynamic Polarization: Scan the potential of the working electrode from a value cathodic to the OCP to a value anodic to the OCP at a slow, controlled scan rate (e.g., 1 mV/s).

- Data Collection: Record the current density response as a function of the applied potential.

- Analysis: Plot the data as potential (E) vs. logarithm of the absolute current density (log |i|). Extrapolate the linear portions of the anodic and cathodic branches to determine the Tafel slopes and corrosion current density. An increased slope or decreased corrosion current may suggest passivation.

Protocol 2: Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDX) Spectroscopy for Fouling Analysis

Objective: Determine the elemental composition of deposits on a fouled electrode to identify the source of contaminants.

Principle: EDX spectroscopy detects characteristic X-rays emitted from a sample when bombarded with electrons, providing quantitative and qualitative data on elemental composition [1].

Materials:

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) equipped with an EDX detector

- Fouled electrode sample

- Sample stubs and conductive tape

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Securely mount the dried fouled electrode sample on a stub using conductive tape to prevent charging.

- Microscopy: Insert the sample into the SEM chamber and evacuate. Obtain a clear secondary electron image of the fouled surface at a suitable magnification.

- Spectroscopy: Position the electron beam on the area of interest (the fouling layer) and activate the EDX detector. Collect the X-ray spectrum for a sufficient time to ensure good counting statistics.

- Multi-point Analysis: Perform EDX analysis at multiple points on the fouling layer and on a clean area of the electrode for comparison.

- Data Interpretation: Identify the elements present in the fouling layer. High carbon and oxygen content may indicate organic fouling, while other metals (e.g., Ca, Fe) suggest inorganic scaling.

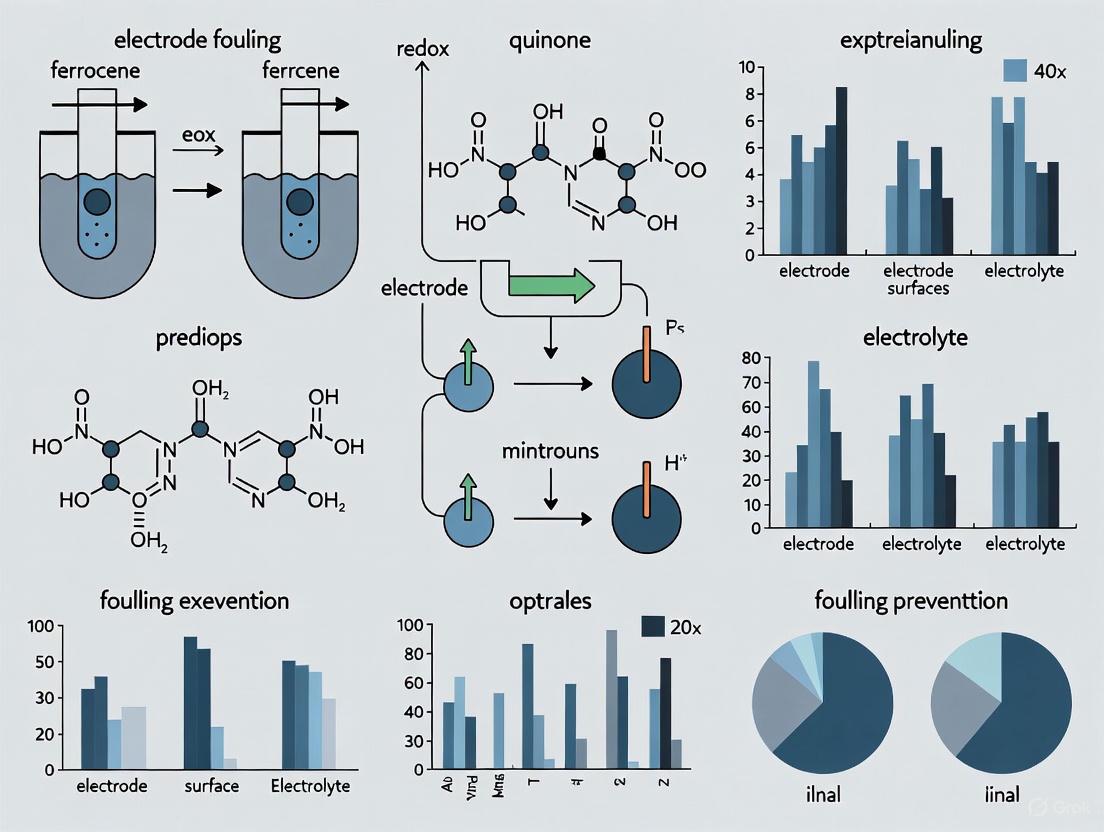

Diagnostic Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for diagnosing and addressing electrode surface issues.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for experiments focused on mitigating electrode fouling and passivation.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers (PEDOT/PSS, PPy/PSS) | Coat porous carbon electrodes to improve reaction selectivity, act as a redox shuttle, and suppress competing reactions like Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) [3]. |

| Aggressive Ions (e.g., Chloride) | Added to electrolyte to compete with oxide formation on electrode surfaces, thereby helping to suppress the growth of passive oxide layers [1]. |

| Thermally/Oxidatively Treated Carbon Felts | Electrodes treated with heat or plasma to enhance surface functional groups, improving wettability and electrocatalytic activity for redox reactions, thus mitigating performance loss [4]. |

| Metal Catalysts (Bi, Ag, Cu) | Electrocatalysts loaded onto carbon felt electrodes to improve charge transfer kinetics and efficiency in systems like Vanadium RFBs, countering losses from passivation [4]. |

| Aluminium Electrodes | Common sacrificial anodes in electrocoagulation systems; their susceptibility to fouling and passivation makes them a key model for studying these phenomena [1] [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Fouling in Redox Systems

This guide helps diagnose and solve common electrode fouling problems encountered during experiments with biofluids.

Table: Troubleshooting Common Fouling Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Fouling Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Performance Metric to Monitor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous drop in current density or power output | Biofilm formation on the electrode surface, leading to increased ohmic resistance and blocked active sites [5]. | Apply a mild cathodic bias (1-5 V); Implement quorum quenching strategies [6] [7]. | Restored voltage efficiency; Reduced transmembrane pressure (TMP) rise [7]. |

| Increased system resistance or overpotential | Accumulation of proteins and cellular debris creating an insulating layer on the electrode [5]. | Optimize hydrodynamic conditions (e.g., cross-flow, air sparging) to increase shear forces [5] [6]. | Power density recovery; Reduction in hydraulic resistance [5]. |

| Rapid capacity decay and reduced Coulombic efficiency | Crossover of organic species and their adsorption onto the electrode, or degradation of active materials [8] [9]. | Use ion-selective membranes; Re-design electrolyte formulations for stability [8]. | Cycle life; Capacity retention per cycle [8]. |

| Visible biofilm or sludge accumulation on components | Mature biofilm formation facilitated by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) [5] [6]. | Introduce mechanical membrane shear (e.g., vibrating, rotating modules) [6]. | Biofilm thickness (e.g., measured via CLSM); EPS quantification [7]. |

| Unstable voltage output during charge/discharge cycles | Fouling leading to inconsistent mass transfer and concentration polarization at the electrode surface [10] [11]. | Reconstruct flow field (e.g., use semicircular channels) to enhance uniform flow distribution [11]. | Concentration uniformity factor; Voltage stability [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary biological components that cause fouling in bioelectrochemical systems? The primary agents are a complex matrix of biological materials. Proteins and Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) form a gel-like layer that adheres to surfaces, creating significant resistance to ion and electron transfer [5]. Cellular debris from lysed cells and Natural Organic Matter (NOM) from the feed solution further contribute to pore blockage and the development of an insulating film [5] [6]. This biofilm matrix is particularly challenging because it continuously regenerates.

Q2: How does the fouling mechanism in redox flow batteries differ from standard biofouling? In redox flow batteries (RFBs) and bioelectrochemical cells (BECs), fouling directly degrades electrochemical function. Unlike in filtration systems where fouling affects hydraulic permeability, in RFBs, even a thin biofilm can cause substantial ohmic losses and disrupt the delicate proton and charge balances essential for current generation and synthesis reactions [5]. Furthermore, crossover and degradation of organic redox-active species can lead to irreversible capacity fade, a unique challenge in aqueous organic RFBs [8].

Q3: What are the most promising anti-fouling strategies for research experiments? Recent advances highlight several effective strategies:

- Electrochemical Mitigation: Applying a mild cathodic bias (1-5 V) has been shown to reduce hydraulic resistance by up to 96% and biofilm thickness by 30% by generating sublethal reactive oxygen species and creating electrostatic repulsion [7].

- Quorum Quenching (QQ): This method disrupts bacterial communication (quorum sensing), a key process in biofilm formation. Using encapsulated QQ enzymes or microbes in MBRs has proven effective in delaying biofouling [6].

- Membrane Surface Engineering: Developing membranes with hydrophilic surfaces, smooth topography, and negative surface charge can reduce the affinity for foulants. Incorporation of antimicrobial agents like silver or graphene oxide is also being explored [5].

- Flow Field Optimization: Modifying the flow channel geometry (e.g., using a semicircular design) can improve the average active ion concentration in the electrode by up to 19.1% and enhance uniformity by 16.2%, thereby mitigating concentration polarization-based fouling [11].

Q4: How can I experimentally monitor and quantify fouling in my lab-scale system? A multi-faceted approach is recommended:

- Electrochemical Performance: Track voltage efficiency, Coulombic efficiency, and power density over time [5] [10].

- Physical Characterization: Use Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) to measure biofilm thickness and structure. Quantify Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) to assess biofilm matrix development [7].

- Hydraulic Monitoring: In filtration-based systems, monitor the Transmembrane Pressure (TMP) rise over time at constant flux, which is a direct indicator of fouling [7].

- Transcriptomic Analysis: For a deep mechanistic understanding, whole-transcriptome RNA sequencing can identify the downregulation of biofilm-related genes (e.g., for EPS and quorum-sensing) in response to anti-fouling treatments [7].

Experimental Protocols for Fouling Mitigation

Protocol 1: Applying Cathodic Bias for Biofouling Control

This protocol details a method to suppress biofilm maturation on conductive surfaces using sublethal electrochemical stress [7].

Workflow Overview

Materials and Reagents

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): Serves as the conductive material for the electrode/membrane.

- Nafion perfluorinated resin solution: Binder for CNTs.

- Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane: Substrate for conductive coating.

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 culture: Model biofilm-forming bacterium.

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat: To apply and control the cathodic bias.

Procedure

- Fabricate the Conductive Electrode/Membrane: Prepare a dispersion of multi-walled CNTs (e.g., 90 mg) in a solution containing Nafion (250 µL) and ethanol (50 mL). Sonicate the mixture and vacuum-filter it onto a PVDF support to create a uniform conductive layer [7].

- Assemble the Flow Cell: Integrate the conductive membrane as the cathode in a filtration cell. Set up the anodic counter electrode and reference electrode if needed.

- Apply Cathodic Bias: Begin constant-flux filtration of the biofluid or bacterial suspension. Apply a continuous DC cathodic bias (optimally between 1-5 V) to the membrane, with the counter electrode as the anode.

- Monitor Performance: Record the Transmembrane Pressure (TMP) every 30 minutes for 24 hours to track fouling behavior.

- Post-experiment Analysis: After the run, analyze the biofilm on the surface using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) for 3D structure and thickness. Quantify EPS components (proteins and polysaccharides) and/or conduct transcriptomic analysis to examine gene expression changes.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Flow Channel Designs to Minimize Fouling

This protocol uses numerical modeling and experimental validation to optimize mass transfer and reduce concentration-based fouling [11].

Workflow Overview

Materials and Reagents

- CAD Software: For designing different flow field geometries (e.g., serpentine flow fields with rectangular, triangular, semicircular channels).

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Software: Platform for running multi-physics numerical simulations (e.g., COMSOL, ANSYS).

- 3D Printer or CNC Machine: For fabricating the optimized flow field plates from graphite or composite materials.

- Electrochemical Test Station: For battery cycling tests, including potentiostat, pumps, and electrolyte reservoirs.

Procedure

- Develop a Numerical Model: Establish a validated three-dimensional model that couples fluid dynamics, mass transport, and electrochemical reactions specific to your redox system.

- Simulate Channel Geometries: Use the model to simulate and compare the performance of different channel cross-sections (e.g., rectangular, triangular, semicircular). Key outputs to analyze are the uniformity factor of reactant concentration across the porous electrode and the average concentration of active ions [11].

- Fabricate the Optimal Design: Based on simulation results, fabricate the flow field plate with the optimal geometry (research indicates semicircular channels often provide superior performance) [11].

- Experimental Validation: Assemble a flow battery or electrochemical cell using the new flow field. Perform repeated charge-discharge cycles.

- Data Collection: Measure and compare the charge/discharge voltages, energy efficiency, and cycle life against a baseline design. The optimized design should exhibit higher discharge voltage, lower charging voltage, and improved stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Fouling Mitigation Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Application / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Prevents crossover of redox species and foulants, reducing capacity decay and electrode poisoning [8]. | Used in VRFBs and AORFBs to separate anolyte and catholyte; research focuses on designing membranes with tailored ion transport channels [8]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Provides a high-surface-area, electrically conductive coating for electrodes/membranes, enabling electrochemical antifouling strategies [7]. | Fabricated into cathodic membranes for applying repulsive bias, reducing TMP rise by up to 50% [7]. |

| Quorum Quenching (QQ) Agents | Disrupts bacterial cell-to-cell communication (Quorum Sensing), preventing coordinated biofilm formation [6]. | Encapsulated enzymes (e.g., acylase) or bacteria used in MBRs to delay biofouling; a biochemical rather than biocidal approach [6]. |

| Silver Nanoparticles / Zeolite / Graphene Oxide | Incorporated into membranes or electrode surfaces to provide antimicrobial properties and mitigate biofouling [5]. | These additives release ions or create nanostructures that inhibit bacterial attachment and growth under laboratory conditions [5]. |

| Ceramic Membranes | Alternative to conventional polymer membranes (e.g., Nafion), offering high chemical stability, resistance to fouling, and often lower cost [5]. | Emerging as a significant contender in bioelectrochemical cells (BECs) due to their durability and performance [5]. |

In electrochemical research, passivation refers to the gradual formation of an inert, non-conductive surface layer—typically metal oxides or hydroxides—on a metal electrode during operation [12]. This phenomenon presents a critical challenge as the passivation layer dynamically evolves during operation, hindering electron transfer and material dissolution by acting as a resistive barrier [13]. Consequently, this leads to decreased electroactivity, increased electrical resistance, and a overall decline in system performance and efficiency. This technical support article addresses these issues within the context of redox systems research, providing troubleshooting guidance and mitigation strategies to maintain experimental integrity and data reliability.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Evidence

The Fundamental Mechanism

At its core, passivation involves the oxidation of the electrode material itself. When a metal anode is oxidized, it releases metal ions [12]. These ions can hydrolyze and form various metal hydroxyl complexes and oxides that adhere to the electrode surface [12]. This thin (typically 10-20 nm) non-conductive surface oxide layer creates a physical and electronic barrier between the electrode and the electrolyte [13]. The layer is often impermeable, preventing the analyte of interest from making physical contact with the electrode surface for efficient electron transfer [14].

Quantitative Impact on System Performance

The table below summarizes documented performance degradation caused by passivation across different electrochemical systems:

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Passivation on Electrochemical Systems

| System Type | Performance Metric | Unpassivated Performance | Passivated Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti in PEM Electrolyzers | Corrosion Current Density | Baseline | 5 orders of magnitude decrease | [15] |

| Ti with ALD TiOx Coating | Dissolution Rate | ~5 nm/year | Not Applicable (coating protects Ti) | [15] |

| Electrocoagulation (EC) | Treatment Efficiency & Energy Use | High efficiency, Lower energy | Decreased efficiency, Increased energy consumption | [12] |

| Electrochemical Micromachining (ECM) | Current Flow & Material Dissolution | Sustained high current | Decreased current, Hindered dissolution | [13] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving Passivation

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Procedure

Figure 1: A workflow for diagnosing and troubleshooting passivation issues in experimental setups.

Detailed Diagnostic Methods

Operando (In-Process) Monitoring:

- Method: Acquire in-process current signals at high frequency (e.g., 10 MHz). Process the data to track pulse duration and current value indicators [13].

- Interpretation: A continuous decrease in current during pulse-ON duration or an abrupt cessation of current flow indicates dynamic passivation layer growth increasing interelectrode gap resistance [13].

Ex-Situ Surface Characterization:

- Techniques: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for surface morphology and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) for elemental mapping of the machined surface [13].

- Expected Findings: Identification of a surface layer composed primarily of metal oxides and hydroxides, distinct from the underlying electrode material [12].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol: Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) of Protective TiOx Coating

Objective: Apply a thin, conformal TiOx coating to serve as an effective oxygen diffusion barrier, preventing further oxidation and corrosion of the underlying titanium substrate [15].

- Materials: Titanium substrate, ALD precursor (e.g., TiCl₄ or Ti-based organometallic), Oxygen source (e.g., H₂O, O₃).

- Procedure:

- Load the titanium substrate into the ALD reactor chamber.

- Heat the substrate to the desired deposition temperature (elevated temperatures can reduce the voltage required for subsequent anodization [15]).

- Expose the substrate to the Ti-precursor pulse, allowing for saturated surface reactions.

- Purge the chamber with an inert gas to remove excess precursor and by-products.

- Expose the substrate to the oxygen source pulse.

- Purge again to remove any residual reactants.

- Repeat steps 3-6 for the number of cycles required to achieve the desired TiOx film thickness.

- Validation: The robustness of the coating should be evaluated under high potentials (e.g., 2.4 V vs. RHE), in low pH (≤5), and at elevated temperature (e.g., 80 °C) to simulate harsh operating conditions [15].

Protocol: Mitigating Passivation via Polarity Reversal in Electrocoagulation

Objective: Periodically reverse the polarity of the electrodes to dissolve the passivation layer that forms on the anode [12].

- Materials: Electrocoagulation reactor, DC power supply capable of polarity switching, Electrodes (e.g., Fe or Al).

- Procedure:

- Set the initial polarity and operate at the desired current density for a set time interval (e.g., 30-60 seconds).

- Program the power supply to automatically switch the polarity of the electrodes for a subsequent, often shorter, time interval.

- This cycle is repeated continuously throughout the operation.

- Key Consideration: The duration of the forward and reverse cycles must be optimized to effectively remove the passivation layer without significantly reducing the overall treatment efficiency [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Passivation Management

| Item | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ALD TiOx Coating | Serves as an oxygen diffusion barrier, drastically reducing substrate corrosion. | Protecting titanium components in low-pH PEM water electrolyzers [15]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Chloride ions (Cl⁻) can compete with oxide formation or locally disrupt the passive layer. | Mitigating anode passivation in electrocoagulation water treatment systems [12]. |

| Pulsed Power Supply | Enables polarity reversal protocols; pulsed operation can help manage layer growth. | Preventing/dissolving passivation layers in electrocoagulation and related setups [12]. |

| Sodium Nitrate (NaNO₃) Electrolyte | A passivating electrolyte that promotes oxide formation on certain metals like Ti alloys. | Used in studies to create passivation-favourable conditions for fundamental research [13]. |

| Carbon Felt Electrodes | High surface area electrodes used in Redox Flow Batteries (RFBs) to minimize local current densities. | A standard electrode material in vanadium and other redox flow battery systems [16]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between passivation and fouling? A1: While often used interchangeably, a key distinction lies in the source of the layer. Passivation typically refers to the formation of a non-conductive layer from the oxidation of the electrode material itself (e.g., titanium oxide on Ti). In contrast, fouling generally involves the passivation of an electrode surface by an external, adsorbed fouling agent (e.g., proteins, phenols, biological molecules) from the electrolyte or a reaction product that forms an impermeable layer [12] [14].

Q2: My experimental current is dropping steadily despite a fixed applied voltage. Is this definitely passivation? A2: A steady decrease in current under constant voltage is a classic symptom of passivation, as the growing oxide layer increases the system's resistance [13]. However, other factors like reactant depletion or changes in electrolyte conductivity can cause similar effects. You should perform the diagnostic steps outlined in Section 3.1 to confirm.

Q3: Are there any benefits to passivation? A3: Yes, passivation is not always detrimental. In many contexts, it is intentionally promoted to enhance a material's corrosion resistance. The stable, dense oxide layer on metals like aluminum or titanium protects the bulk material from further degradation in corrosive environments [15] [17]. The challenge in electrochemical devices is managing this phenomenon to prevent unwanted performance loss.

Q4: How does a simple technique like polarity reversal work to mitigate passivation? A4: Polarity reversal periodically switches the anode and cathode. When the passivated electrode becomes the cathode, reduction reactions occur on its surface. These reactions can chemically reduce the metal oxides in the passivation layer (e.g., converting Fe₂O₃ back to soluble Fe²⁺ ions), thereby dissolving it and reactivating the electrode surface for the next cycle [12].

Q5: For a highly passivating material like Ti6Al4V, what advanced methods can improve processability? A5: Beyond coatings and polarity reversal, hybrid manufacturing approaches show promise. For example, Hybrid Laser-ECM (LECM) simultaneously applies laser and electrochemical energies at the same machining zone. The laser energy locally weakens or disrupts the passive layer, which enhances electrochemical reaction kinetics and significantly improves material dissolution rates in otherwise difficult-to-process materials [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary consequences of electrode fouling in electrochemical assays? Electrode fouling negatively impacts assay performance through three primary consequences: (1) Sensitivity Loss: The accumulation of foulants on the electrode surface creates a physical barrier, reducing the electrode's active area and hindering electron transfer, which diminishes the signal response for a given analyte concentration [18]. (2) Signal Drift: Unwanted materials slowly accumulating on the sensor surface cause a gradual, time-dependent change in the baseline signal, often due to ionic diffusion or chemical alteration of the electrode material [19] [20]. (3) Reduced Reproducibility: Fouling introduces unpredictable variations in electrode response, leading to poor repeatability and reproducibility of measurements over time and across different experimental setups [19] [21].

FAQ 2: What is the difference between biofouling and chemical fouling? Biofouling and chemical fouling are distinct mechanisms leading to performance degradation.

- Biofouling refers to the accumulation of biomolecules (e.g., proteins, lipids) from complex biological matrices onto the electrode surface [18]. For example, proteins like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) can adsorb and form an insulating layer [18].

- Chemical Fouling is caused by the deposition of chemical species, such as by-products from the redox reactions of the target analytes themselves. For instance, neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine can form oxidative by-products that strongly adhere to the electrode surface [18].

FAQ 3: How can I confirm that signal drift in my experiment is due to electrode fouling? Implementing a rigorous testing methodology is key to confirming fouling-related drift. This includes:

- Stable Electrical Configuration: Use a stable pseudo-reference electrode (e.g., Pd) to minimize external contributions to drift [20].

- Infrequent DC Sweeps: Rely on infrequent DC current-voltage sweeps rather than continuous static measurements or complex AC measurements to better isolate the signal from drift [20].

- Control Experiments: Always run control experiments with a device that lacks the specific biorecognition element (e.g., no antibodies printed on the channel). This confirms that any signal change is due to specific binding and not a time-based artifact [20].

FAQ 4: My External Quality Assessment (EQA) results show a deviation. How do I troubleshoot if it's related to fouling? Deviations in EQA can stem from fouling, which introduces systematic errors (bias) or random errors (imprecision). Follow a structured troubleshooting flowchart [22]:

- Verify Clerical Accuracy: Confirm the reported result, units, and decimal points are correct.

- Check Internal Quality Control (IQC): Review IQC data from the time of EQA testing. Look for shifts or trends that indicate a systematic issue.

- Investigate Instrument and Reagents: Review calibration status, instrument maintenance logs, and reagent conditions (preparation, storage, open-vial stability). A change in reagent batch can sometimes cause effects similar to fouling.

- Re-run the Sample: If the problem persists, it likely indicates a systematic error (like fouling). If the re-run is acceptable, the initial error was likely random.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide for Diagnosing and Mitigating Sensitivity Loss

Sensitivity loss manifests as a decreased signal for a known concentration of analyte.

- Problem: Gradual decrease in peak current over multiple measurements in Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV).

- Primary Cause: Fouling layer (biofouling or chemical fouling) acting as an insulating barrier on the working electrode surface [18].

- Solution:

- Diagnosis: Characterize the fouling mechanism by reviewing your experimental conditions. Was the electrode exposed to complex media (biofouling) or analytes prone to polymerization like serotonin (chemical fouling)? [18].

- Mitigation: Apply anti-fouling coatings to the electrode. Common strategies include:

- Passive Coatings: Use polymer brushes like poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) or PEDOT-based films (PEDOT:Nafion, PEDOT-PC) to create a physical, non-fouling barrier that repels biomolecules [20] [18].

- Active Strategies: For membranes, strategies include creating surfaces that release antifoulants or have photocatalytic properties [23]. While more common in separation membranes, the principle of active defense can inform sensor design.

- Correction: Implement a regular electrode cleaning and re-polishing protocol to restore the active surface. The frequency should be determined empirically based on the experiment.

Guide for Diagnosing and Correcting Signal Drift

Signal drift is a continuous, often monotonic, change in the baseline signal over time.

- Problem: Baseline in a BioFET or potentiometric sensor shifts upward or downward during measurement in solution.

- Primary Cause: Slow diffusion of electrolytic ions into the sensing region, altering gate capacitance and threshold voltage, or chemical alteration of the electrode material itself [19] [20].

- Solution:

- Diagnosis:

- Mitigation:

- Device Passivation: Properly encapsulate and passivate the electronic components to minimize leakage currents and stabilize the electrical environment [20].

- Stable Reference Electrodes: Protect Ag/AgCl electrodes from sulfide ions, or consider using stable pseudo-reference electrodes (e.g., Pd) where appropriate [20] [18].

- Optimized Measurement: Use a measurement protocol that relies on infrequent DC sweeps instead of continuous static monitoring [20].

Guide for Diagnosing and Restoring Reproducibility

Reduced reproducibility is characterized by high variability in results for the same sample across different runs, days, or electrodes.

- Problem: High coefficient of variation (%CV) for replicate measurements, or inconsistent results from one EQA cycle to the next.

- Primary Cause: Inconsistent electrode surface states caused by uneven fouling, inadequate cleaning protocols, or failure to account for between-lot variations in reagents [24] [21].

- Solution:

- Diagnosis:

- Analyze EQA/QC results over time using Levey-Jennings charts to identify shifts or trends [22].

- Check if all affected parameters show the same deviation, which might point to a general issue like sample reconstitution error, or if only one parameter is affected, indicating a specific fouling or reagent issue [24] [22].

- Mitigation:

- Standardized Conditioning: Establish and strictly adhere to a standardized electrode conditioning protocol before each measurement. Studies on nitrate sensors show that a consistent and sufficiently long conditioning period is critical for reproducible signals, even after long-term storage [21].

- Reagent Management: Monitor and document reagent batch numbers. Between-lot variations can introduce bias that mimics the effects of fouling [24].

- Preventive Maintenance: Implement a rigorous and documented schedule for instrument maintenance, calibration, and pipette verification [22].

- Diagnosis:

The table below summarizes experimental data on the impact of different fouling mechanisms from key studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Fouling Mechanisms on Assay Performance

| Fouling Mechanism | Experimental Model | Measured Performance Loss | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biofouling [18] | FSCV with CFME in BSA (40 g/L) | Sensitivity & Signal Shift | Sensitivity Decrease: ~20% after 2 hours Peak Voltage Shift: ~+0.12 V observed |

| Chemical Fouling (Serotonin) [18] | FSCV with CFME in 25 µM 5-HT | Sensitivity & Signal Shift | Sensitivity Decrease: >50% after only 5 minutes Peak Voltage Shift: ~+0.15 V observed |

| Chemical Fouling (Sulfide Ions) [18] | Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Reference Potential Shift | Open Circuit Potential (OCP): Decreased upon S²⁻ exposure Result: Causes peak voltage shifts in FSCV voltammograms |

| General Passivation [12] | Electrocoagulation Anodes | Operational Efficiency | Energy Consumption: Increases due to passivation layer Treatment Efficiency: Decreases over time, limiting wide application |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Investigating Biofouling and Chemical Fouling on Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes (CFMEs)

This protocol is adapted from to characterize fouling effects in FSCV applications [18].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Tris Buffer (15 mM Trizma HCl, 10 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) | Electrochemical background electrolyte solution. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Model protein to simulate biofouling. Dissolve at 40 g/L in Tris buffer [18]. |

| F12-K Gibco Nutrient Mix | Complex medium to simulate a more realistic biofouling environment [18]. |

| Dopamine Hydrochloride (DA) | Neurotransmitter analyte and agent for chemical fouling. Prepare 1 mM stock in Tris buffer [18]. |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | Neurotransmitter analyte known to cause severe chemical fouling. Prepare 1 mM stock in Tris buffer [18]. |

| Carbon Fiber Microelectrode (CFME) | Working electrode. Fabricated from a single 7µm carbon fiber insulated in a silica capillary [18]. |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Reference electrode. Fabricated from chloridized silver wire [18]. |

II. Methodology

- Baseline Stabilization and Measurement:

- Place the CFME and Ag/AgCl reference electrode in a Tris buffer solution.

- Apply the appropriate FSCV waveform (e.g., triangle waveform from -0.4 V to 1.0 V at 400 V/s for dopamine) at 10 Hz until a stable background current is achieved.

- Record multiple stable voltammograms as the pre-fouling baseline.

Fouling Induction:

- For Biofouling: Transfer the electrodes to a solution of either BSA (40 g/L) or F12-K Nutrient Mix, while continuously applying the FSCV waveform for 2 hours [18].

- For Chemical Fouling (Dopamine): Submerge the electrodes in a Tris buffer solution containing 1 mM dopamine for 5 minutes with the waveform applied [18].

- For Chemical Fouling (Serotonin): Submerge the electrodes in a Tris buffer solution containing 25 µM serotonin for 5 minutes while applying a serotonin-specific "Jackson" waveform [18].

Post-Fouling Measurement:

- Carefully rinse the electrodes with clean Tris buffer to remove loosely adsorbed foulants.

- Return the electrodes to a fresh Tris buffer solution.

- Re-run the FSCV measurement and record the post-fouling voltammograms.

Data Analysis:

- Sensitivity Loss: Compare the peak oxidation current of a standard analyte (e.g., 1 µM dopamine) before and after fouling.

- Signal Shift: Measure the change in the voltage (V) at which the oxidation peak occurs.

- Reproducibility: Perform the experiment with at least 3-5 electrodes (n) and report the mean ± standard deviation.

Diagram 1: CFME Fouling Experiment Workflow

Protocol: Mitigating Drift in Carbon Nanotube (CNT) BioFETs

This protocol outlines the key steps for fabricating and operating a stable D4-TFT (BioFET) device to mitigate signal drift in high ionic strength solutions [20].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Semiconducting Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | The highly sensitive channel material for the BioFET transistor [20]. |

| Poly(oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate) (POEGMA) | A polymer brush layer that extends the Debye length and serves as a non-fouling, hydrophilic matrix for bioreceptor immobilization [20]. |

| Capture Antibodies (cAb) | Specific antibodies printed into the POEGMA layer to capture the target analyte [20]. |

| Palladium (Pd) Pseudo-Reference Electrode | A stable, low-cost alternative to bulky Ag/AgCl reference electrodes, suitable for point-of-care devices [20]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 1X | Biologically relevant ionic strength solution for testing. |

II. Methodology

- Device Fabrication:

- Fabricate a thin-film transistor (TFT) using a network of semiconducting CNTs as the channel.

- Functionalize the CNT channel and surrounding area with a POEGMA polymer brush layer via surface-initiated polymerization. This coating is critical for mitigating biofouling and overcoming charge screening.

- Key Step: Inkjet-print the capture antibodies (cAb) into the pre-defined POEGMA matrix above the CNT channel.

- Critical for Drift Mitigation: Implement proper device encapsulation/passivation around the active area to prevent leakage currents [20].

- Integrate a Pd pseudo-reference electrode into the system.

Stable Measurement Operation:

- Operate the device in a solution of 1X PBS.

- Use a stable electrical testing configuration with the Pd reference electrode.

- Key Methodology for Drift Mitigation: To minimize drift, avoid continuous static (DC) measurements. Instead, use a protocol of infrequent DC current-voltage (I-V) sweeps to collect data points [20]. This reduces the exposure time to electrolytic effects that cause drift.

- Include a control device on the same chip where no antibodies are printed over the CNT channel. This confirms that signal changes are due to specific binding and not drift.

Data Analysis:

- Monitor the shift in the transistor's on-current (I_on) between the antibody-containing device and the control device.

- A stable, drift-free baseline in the control device, coupled with a specific I_on shift in the active device, confirms successful and reliable analyte detection.

Diagram 2: D4-TFT Drift Mitigation Strategy

Electrode fouling is a critical challenge in electrochemical systems, characterized by the passivation of the electrode surface by fouling agents that form an impermeable layer, inhibiting analyte contact and electron transfer [25]. In redox flow batteries (RFBs) and electrocoagulation systems, this phenomenon severely impacts sensitivity, reproducibility, energy efficiency, and long-term reliability [1] [26] [25]. This technical support guide addresses the key operating parameters—current density, voltage, and electrolyte composition—that influence fouling, providing researchers and scientists with troubleshooting FAQs and detailed protocols to mitigate these issues within the context of redox systems research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do excessive current density and upper cut-off voltage accelerate fouling and degradation in my redox flow battery?

- Observed Problem: Rapid decrease in capacity retention and voltage efficiency during cycling, along with increased cell resistance.

- Root Cause: Operating at excessively high current densities or upper cut-off voltages promotes several degradation pathways. High voltages, particularly above 1.6 V in vanadium systems, can accelerate the oxidation of carbon-based electrodes and promote undesirable side reactions like hydrogen evolution [27]. These reactions degrade electrode materials and alter electrolyte composition, leading to performance fade.

- Solution:

- Optimize Voltage Limits: For vanadium RFBs, maintain the upper cut-off voltage at or below 1.6 V during cycling. Studies show that increasing the voltage to 1.7 V and 1.8 V significantly decreases capacity and voltage efficiencies, with only partial recovery after electrolyte remixing, indicating permanent cell damage [27].

- Apply CCCV Charging: Consider using a constant current–constant voltage (CCCV) charging method instead of constant current (CC). The CCCV method has been shown to yield better voltage efficiencies and support long-term cycling stability in iron/iron RFBs [28].

FAQ 2: Why does my electrolyte composition lead to membrane fouling and crossover, and how can I prevent it?

- Observed Problem: Decline in coulombic efficiency, changes in electrolyte balance, and increased membrane resistance, potentially due to active species crossover and fouling.

- Root Cause: The composition of the electrolyte directly influences the stability of active species and their interaction with membranes. In non-aqueous flow batteries, membrane fouling—not side reactions—can be the primary driver of early performance fade [26]. Crossover rates can shift from Fickian to non-Fickian transport as cycling progresses.

- Solution:

- Utilize Additives and Complexation: Introduce chemical additives that modify species transport. In a redox-flow desalination system for battery recycling, adding Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) to form a complex with Ni²⁺ (NiY²⁻) enabled its selective separation through an anion-exchange membrane (AEM), preventing crossover and improving recovery [29].

- Adjust Proton and Vanadium Concentration: For vanadium RFBs, readjusting asymmetrical electrolyte concentrations in the half-cells can help reduce electrolyte imbalance caused by crossover phenomena, though this involves a trade-off between battery capacity and energy efficiency [30].

FAQ 3: What strategies can I use to mitigate fouling when the analyte itself is the fouling agent?

- Observed Problem: Fouling occurs even when analyzing target analytes, such as phenols or neurotransmitters, which form polymeric films on the electrode surface during their redox reaction [25].

- Root Cause: The reaction products of the analyte polymerize on the electrode surface, forming an impermeable layer that blocks active sites.

- Solution:

- Electrode Surface Modification: Employ advanced electrode materials or coatings. Coatings using carbon nanotubes, graphene, or metallic nanoparticles can provide fouling resistance due to their large surface area, electrocatalytic properties, and tailored surface chemistry [25].

- Use Protective Polymer Films: Modify the electrode with protective polymers like Nafion, poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), or poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) to create a physical barrier that prevents the fouling agent from reaching the electrode surface [25].

Table 1: Key Operating Parameters and Their Influence on Fouling and System Performance

| Parameter | Optimal Range / Condition | Impact of Deviation | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Cut-off Voltage | ≤ 1.6 V (for VRFBs) [27] | High (>1.6 V): Accelerated carbon electrode oxidation, H₂ evolution, electrolyte imbalance, permanent efficiency loss [27] | Implement CCCV charging; Use voltage limits of 1.6-1.65 V [28] [27] |

| Current Density | System-specific optimized range | Excessive: Increased side reactions, rapid electrode passivation, faradaic losses [1] | Optimize for coagulant production (electrocoagulation) or redox reactions; avoid over-potentials [1] |

| Electrolyte Composition | Stable species with additives | Unoptimized: Species disproportionation, membrane fouling, non-Fickian crossover, performance fade [26] [30] | Use complexing agents (e.g., EDTA); Adjust proton/vanadium concentration asymmetry [29] [30] |

| Flow Rate / Hydrodynamics | Sufficient to minimize concentration polarization | Too Low: Promotes contaminant buildup and salt precipitation on electrode and membrane surfaces [1] | Ensure proper mixing and turbulence to sweep away fouling agents from active surfaces |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Tafel Analysis for Investigating Electrode Passivation

This protocol is used to quantify the corrosion and passivation behavior of electrodes, particularly in electrocoagulation systems using aluminium electrodes [1].

- Cell Setup: Use a standard three-electrode configuration with the electrode material of interest (e.g., Al) as the working electrode, an appropriate counter electrode (e.g., platinum), and a stable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl).

- Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare the electrolyte solution that matches the system under study (e.g., synthetic brackish peat water or tannery wastewater).

- Polarization Measurement: Run a potentiodynamic polarization scan, typically from -0.25 V to +0.25 V relative to the open circuit potential, at a slow scan rate (e.g., 0.166 mV/s) [1].

- Data Analysis: Plot the applied potential (E) against the logarithm of current density (log i). The Tafel equation (η = a ± b log i) is used to analyze the plot, where 'b' is the Tafel slope.

- Interpretation: An increasing Tafel slope indicates the formation of a passive layer (e.g., aluminium oxide) on the electrode surface, which is a primary indicator of passivation. This analysis helps in evaluating the effectiveness of different mitigation strategies [1].

Protocol 2: Functionalized Membrane Fabrication for Selective Ion Transport

This methodology describes the creation of a cation-exchange membrane (CEM) functionalized to be monovalent-selective, used in redox-flow desalination for separating Li⁺ from Ni²⁺ and Co²⁺ [29].

- Material Preparation: Obtain a standard CEM. Prepare aqueous solutions of poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) and poly(styrene sulfonate) (PSS).

- Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Assembly: Immerse the CEM sequentially into the polyelectrolyte solutions to build multilayers on its surface.

- First, immerse the membrane in the PAH solution for a set time (e.g., 20 minutes) to adsorb a positive layer.

- Rinse with deionized water to remove loosely bound polymers.

- Next, immerse the membrane in the PSS solution for the same duration to adsorb a negative layer.

- Rinse again. This completes one bilayer (PAH/PSS).

- Repeat: Repeat the sequential immersion cycle multiple times (e.g., 5.5 bilayers) to achieve the desired thickness and selectivity [29].

- Characterization: The resulting f-CEM enables selective transport of monovalent cations (like Li⁺) while repelling divalent cations (like Ni²⁺ and Co²⁺) due to the enhanced electrostatic repulsion and sieving effect of the multilayer film [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Fouling Mitigation Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Feature / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(allylamine hydrochloride) / Poly(styrene sulfonate) (PAH/PSS) | Functionalization of CEMs for monovalent ion selectivity [29] | Creates a tunable, layered surface that sieves ions based on charge density and hydrated radius [29] |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | Chelating agent for selective metal ion separation [29] | Binds specific divalent cations (e.g., Ni²⁺) to form anionic complexes (NiY²⁻), enabling transport through AEMs [29] |

| Water-soluble Redox Polymer (e.g., P(TMA-co-TMPMA-co-METAC)) | Mediator in redox-electrodialysis for desalination/PFAS removal [31] | Replaces expensive AEMs with nanofiltration membranes, reduces fouling, and drives continuous ion migration [31] |

| Nanofiltration (NF) Membrane (1 kDa MWCO) | Size-exclusion membrane in redox-polymer electrodialysis [31] | Cost-effective; enables electric field-driven removal of diverse contaminants without membrane fouling [31] |

| Carbon Nanotube / Graphene Coatings | Fouling-resistant electrode coatings [25] | Provide high surface area, electrocatalytic properties, and resistance to surface passivation [25] |

Experimental Workflow for Fouling Mitigation

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for diagnosing and addressing fouling issues in electrochemical systems.

Diagram 1: Systematic troubleshooting workflow for electrode fouling.

Innovative Materials and Surface Modifications for Robust Antifouling Electrodes

Electrode fouling is a pervasive challenge in electrochemical research, particularly in redox systems and drug development. It involves the passivation of an electrode surface by organic molecules (e.g., proteins, phenols, neurotransmitters), forming an impermeable layer that inhibits the analyte's direct contact with the electrode surface, thereby degrading sensitivity, detection limit, and reproducibility [32]. Conductive polymers (CPs) like Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)/poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT/PSS) and Polypyrrole (PPy) present a powerful solution. Their unique combination of high conductivity, stability, and tunable surface properties allows them to act as a selective barrier, suppressing competing reactions like the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER) and mitigating fouling [32] [33]. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers integrating these advanced coatings into their experiments.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: My PEDOT/PSS coated electrode shows unexpectedly high impedance. What could be the cause?

High impedance often stems from the inherent properties of pristine PEDOT:PSS, which can have low conductivity (< 1 S/cm) due to an excess of insulating PSS chains that disrupt the conductive pathway [34].

- Solution: Incorporate second dopants into your formulation. Chemicals like dimethyl sulfate (DMSO) or ionic liquids can significantly enhance conductivity by reorganizing the PEDOT and PSS chains, leading to a more favorable morphology for charge transport [34].

- Preventive Measure: Always characterize the conductivity of your PEDOT:PSS film after deposition. Optimize the doping concentration to balance conductivity with other required properties like biocompatibility or mechanical flexibility.

Q2: How can I improve the adhesion of electropolymerized Polypyrrole coatings on metal substrates?

Poor adhesion is a common issue with electropolymerized PPy, leading to delamination and insufficient protection [35].

- Solution: Employ an inverted-electrode electropolymerization strategy. This method involves using the metal substrate as the counter electrode during polymerization. Research has demonstrated that this technique produces PPy coatings (PPy-I) with significantly better adhesion strength and a more compact structure compared to those produced by traditional methods (PPy-T) [35].

- Alternative Solution: Consider a bilayer approach or copolymerization. Fabricating a primer layer (e.g., poly(2-amino-5-mercapto-1,3,4-thiadiazole)) before PPy deposition has been shown to improve adhesion and corrosion resistance on stainless steel [35].

Q3: My conductive polymer coating is failing prematurely in a biological medium. What might be happening?

Failure in biological media is frequently due to fouling by proteins or other biological macromolecules. These agents adsorb to the coating surface through hydrophobic or electrostatic interactions, forming an insulating layer [32].

- Solution: Increase the hydrophilicity of the coating surface. Fouling via hydrophobic interactions is often irreversible in aqueous systems; therefore, enhancing hydrophilicity can reduce protein adsorption [32].

- Solution: For PEDOT:PSS, leverage its natural polyelectrolyte structure. The negatively charged PSS chains can create a hydrophilic and potentially protein-repelling surface. Further modification with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) derivatives can also impart antifouling properties [32] [34].

Q4: How do I ensure my PEDOT/PSS coating is selective against the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (HER)?

The primary mechanism is the coating's ability to act as a physical and electrochemical barrier.

- Strategy: The coating should be dense and non-porous to limit the diffusion of hydronium ions (H₃O⁺) to the underlying metal cathode surface. A compact PPy coating fabricated via the inverted-electrode method has been shown to effectively confine ion diffusion, a principle that applies directly to HER suppression [35].

- Strategy: The polymer's stable redox state within the operating potential window can prevent the cathode from reaching the very negative potentials required to drive HER [33].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Fabricating a Robust, Adherent Polypyrrole Coating via Inverted-Electrode Electropolymerization

This protocol is optimized for corrosion protection on copper substrates, directly contributing to HER suppression by forming a dense barrier [35].

- Objective: To deposit a compact and strongly-adhered PPy coating on a copper substrate to serve as a protective barrier.

Materials & Reagents:

- Substrate: Copper sheet (T3 purity).

- Electrolyte: 0.3 M oxalic acid solution containing 0.1 M pyrrole monomer.

- Cleaning Agents: Absolute ethanol, deionized water.

- Equipment: Standard three-electrode electrochemical cell, potentiostat (e.g., Autolab PGSTAT302N), Ag/AgClsat reference electrode.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Substrate Preparation: Mechanically grind the copper sheet with emery paper up to 2000 grit. Clean ultrasonically in absolute ethanol, dry under nitrogen, and store in a desiccator [35].

- Passivation: Assemble a standard three-electrode system (Copper = Working Electrode, Pt wire = Counter Electrode, Ag/AgClsat = Reference). Perform Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for 5 cycles from -0.5 V to 1.1 V (vs. Ag/AgClsat) at 20 mV/s in the 0.3 M oxalic acid electrolyte (monomer-free). This creates a passivated copper surface (P-Cu) [35].

- Inverted-Electrode Polymerization: Reconfigure the electrochemical cell:

- Working Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Counter Electrode: The passivated copper substrate (P-Cu).

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgClsat.

- Perform CV for 20 cycles from -0.6 V to 0.1 V (vs. Ag/AgClsat) at 20 mV/s in the pyrrole-containing oxalic acid electrolyte [35].

- Post-treatment: Remove the coated copper specimen, rinse gently with deionized water, and vacuum-dry at 323 K (50 °C) [35].

Diagram 1: Inverted-electrode workflow for robust PPy coating.

Protocol: Enhancing Conductivity of PEDOT:PSS Coatings with Second Dopants

This protocol is crucial for applications requiring high charge injection capacity, such as in biosensors or stimulating electrodes [34].

- Objective: To significantly increase the electrical conductivity of a spin-coated PEDOT:PSS film.

Materials & Reagents:

- Base Solution: Aqueous PEDOT:PSS dispersion.

- Second Dopant: Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or an ionic liquid.

- Substrate: Any target substrate (e.g., glassy carbon, ITO, flexible PET).

- Equipment: Spin coater, hot plate, conductivity probe.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Solution Preparation: Mix the PEDOT:PSS dispersion with a predetermined volume percentage of your second dopant (e.g., 5% v/v DMSO). Stir thoroughly to ensure homogeneity [34].

- Filter the mixture using a syringe filter (e.g., 0.45 µm) to remove any aggregates.

- Deposition: Spin-coat the doped PEDOT:PSS solution onto your target substrate. Optimize spin speed and time for desired thickness.

- Annealing: Bake the film on a hot plate at an elevated temperature (e.g., 110-140 °C) for 10-20 minutes to remove residual water and enhance molecular ordering [34].

- Validation: Measure the sheet resistance of the film using a four-point probe to calculate conductivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 1: Key reagents for working with PEDOT:PSS and Polypyrrole.

| Reagent | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Pyrrole Monomer | Electropolymerization precursor for PPy coatings [35]. | Must be distilled and stored in the dark under inert atmosphere to prevent premature oxidation [35]. |

| Oxalic Acid | Supporting electrolyte for PPy electropolymerization on copper. Promotes adhesion and passivation [35]. | The passivation step is critical for forming a uniform, adherent PPy layer on copper. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | Second dopant for PEDOT:PSS. Dramatically enhances electrical conductivity [34]. | Optimal concentration is typically 3-5% v/v. Higher amounts may compromise mechanical integrity. |

| TBATF / LiTFSI Salts | Common electrolytes in organic solvents for electrochemical characterization (e.g., propylene carbonate) [36]. | The choice of electrolyte cation (Li⁺, TBA⁺) can influence whether actuation is cation or anion-driven [36]. |

| PEDOT:PSS Aqueous Dispersion | Ready-to-use solution for spin, spray, or dip coating [34]. | Pristine dispersion has low conductivity (<1 S/cm) and requires doping for most applications [34]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Performance of PEDOT Coatings

Table 2: Comparison of PEDOT films synthesized via different electrochemical methods. Data adapted from [36].

| Polymerization Method | Specific Capacitance (F g⁻¹) | Capacitance Retention (after 5000 cycles) | Actuation Mechanism | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiostatic (PEDOT-pot) | 175 | 86.7% | Cation-driven | Higher electronic conductivity, superior capacitance retention [36]. |

| Galvanostatic (PEDOT-galv) | ~80 (2.2x lower) | Not Specified | Anion-driven | Lower energy storage capability [36]. |

Anticorrosion Performance of Optimized PPy Coatings

Table 3: Efficacy of inverted-electrode PPy coating (PPy-I) for copper protection in artificial seawater. Data based on [35].

| Coating Type | Adhesion Strength | Coating Compactness | Corrosion Protection Efficacy | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional PPy (PPy-T) | Poor | Porous, inferior barrier | Moderate | Baseline performance |

| Inverted-Electrode PPy (PPy-I) | Satisfactory/Strong | Compact Structure | Superior | Excellent adhesion and confined ion diffusion, providing robust protection [35]. |

Diagram 2: Antifouling mechanism of conductive polymer coatings.

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My BSA/g-C3N4 coating solution appears cloudy and forms aggregates before application. What is the cause and how can I fix it? A: Cloudiness and aggregation typically indicate improper dispersion of g-C3N4 or a too-rapid mixing process. This compromises the uniformity of the 3D porous matrix.

- Cause 1: Incomplete exfoliation of bulk g-C3N4 into 2D nanosheets. Bulk particles cannot integrate homogeneously into the BSA matrix.

- Solution: Ensure thorough exfoliation. Re-sonicate your g-C3N4 dispersion at a higher power (e.g., 500-600 W) for at least 2 hours. Centrifuge at 5,000 rpm for 15 minutes to remove any unexfoliated material before use.

- Cause 2: The pH of the BSA solution is too close to its isoelectric point (pI ~4.7), causing BSA to precipitate and crash out of solution.

- Solution: Prepare the BSA solution in a phosphate buffer (e.g., 10 mM, pH 7.4) to keep BSA molecules solubilized and charged, facilitating stable integration with g-C3N4.

Q2: The fouling resistance of my coated electrode decreases significantly after 10 electrochemical cycles. How can I improve coating stability? A: This is a classic sign of poor cross-linking within the nanocomposite matrix, leading to dissolution or delamination.

- Cause: Insufficient cross-linking of the BSA matrix. The physical entrapment of g-C3N4 is not enough for long-term stability under electrochemical stress.

- Solution: Optimize the cross-linking protocol with EDC/NHS chemistry.

- Increase the cross-linking reaction time from 2 hours to 4-6 hours.

- Ensure a molar ratio of EDC to BSA carboxyl groups of at least 2:1, with NHS at a 1:1 ratio to EDC.

- After coating, rinse thoroughly with deionized water to remove any unreacted cross-linkers that could interfere with electrochemical performance.

Q3: My electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data shows high charge transfer resistance (Rct) even for the bare electrode after coating. What went wrong? A: A uniformly high Rct suggests the coating is too thick or dense, creating a significant barrier to electron transfer, which defeats the purpose of a fouling-resistant, yet electrochemically active, coating.

- Cause: Applying an excessively thick coating layer, which blocks the redox probe from reaching the electrode surface.

- Solution: Optimize the coating application technique. If using drop-casting, reduce the volume of the coating solution (e.g., from 10 µL to 5 µL). If using spin-coating, increase the spin speed (e.g., from 2000 rpm to 4000 rpm) to create a thinner, more uniform film. The goal is a nanoporous, not a dense, layer.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Non-uniform coating surface | Inconsistent drying; contaminated electrode surface. | Ensure level placement during drying; clean electrode with alumina slurry and ethanol prior to coating. |

| Low g-C3N4 fluorescence in matrix | g-C3N4 nanosheets are too thick (incompletely exfoliated). | Re-sonicate bulk g-C3N4; use supernatant after centrifugation. Confirm exfoliation via UV-Vis (absorption peak ~380 nm) and TEM. |

| Poor fouling resistance to proteins | Incorrect BSA:g-C3N4 ratio; low cross-linking density. | Titrate the BSA:g-C3N4 ratio (see Table 1). Increase EDC/NHS concentration and reaction time. |

| High background current in CV | Unreacted cross-linkers or salts trapped in the matrix. | Perform extensive rinsing with DI water post-coating and after cross-linking. Soak the coated electrode in buffer for 1 hour before use. |

Table 1: Optimization of BSA to g-C3N4 Mass Ratio for Fouling Resistance. Performance measured after exposing coated electrodes to 1 mg/mL BSA solution for 30 minutes. Signal retention calculated from the peak current of 1 mM Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻ before and after fouling.

| BSA : g-C3N4 Ratio | Coating Thickness (nm) | Porosity (%) | Signal Retention (%) | Stability (Cycles to 90% Signal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:0 (BSA only) | 150 ± 10 | 25 ± 5 | 40 ± 8 | 15 ± 3 |

| 5:1 | 180 ± 15 | 45 ± 7 | 75 ± 6 | 45 ± 5 |

| 2:1 | 210 ± 20 | 60 ± 5 | 95 ± 3 | 100+ |

| 1:1 | 250 ± 25 | 55 ± 6 | 90 ± 4 | 85 ± 8 |

| 1:2 | 290 ± 30 | 40 ± 8 | 65 ± 7 | 50 ± 7 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Exfoliated g-C3N4 Nanosheets

- Starting Material: Place 1 g of bulk melamine-derived g-C3N4 powder into a 250 mL beaker.

- Dispersion: Add 100 mL of deionized water.

- Exfoliation: Sonicate the suspension using a probe sonicator (600 W, 20 kHz) for 2 hours in an ice-water bath to prevent overheating.

- Separation: Centrifuge the resulting milky suspension at 5,000 rpm for 15 minutes.

- Collection: Carefully collect the yellow-colored supernatant, which contains the exfoliated g-C3N4 nanosheets. Discard the pellet.

- Characterization: Confirm exfoliation by measuring the UV-Vis spectrum (characteristic peak shift to ~380 nm) and by TEM imaging.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of 3D Porous BSA/g-C3N4 Nanocomposite Coating

- Solution Preparation:

- Prepare a 20 mg/mL BSA solution in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4).

- Prepare a 2 mg/mL dispersion of exfoliated g-C3N4 nanosheets in DI water.

- Mixing: Combine the BSA solution and g-C3N4 dispersion at a 2:1 mass ratio (e.g., 1 mL BSA solution + 0.5 mL g-C3N4 dispersion). Vortex gently for 30 seconds.

- Cross-linking: Add 20 µL of a fresh EDC solution (400 mM) and 20 µL of an NHS solution (100 mM) to the mixture. Vortex gently and allow the cross-linking reaction to proceed for 4 hours at room temperature under mild agitation.

- Electrode Coating: Clean the working electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon) thoroughly. Drop-cast 5 µL of the final BSA/g-C3N4 nanocomposite solution onto the electrode surface.

- Drying & Curing: Allow the coated electrode to dry overnight in a clean, level environment at room temperature.

- Rinsing: Before electrochemical testing, rinse the electrode gently but thoroughly with DI water to remove any loosely bound material.

Visualizations

Title: Coating Fabrication Workflow

Title: Fouling Resistance Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | The protein scaffold for the 3D matrix; provides biocompatibility and functional groups (-COOH, -NH₂) for cross-linking. |

| Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C3N4) | 2D nanomaterial that enhances structural integrity, increases porosity, and provides fouling resistance via hydrophilic and steric repulsion. |

| N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) | Zero-length cross-linker that activates carboxyl groups (on BSA/g-C3N4) for conjugation with primary amines. |

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) | Stabilizes the EDC-activated intermediate, forming a stable amine-reactive ester, greatly improving cross-linking efficiency. |

| Phosphate Buffer (pH 7.4) | Maintains physiological pH to keep BSA soluble and stable during the coating process. |

| Potassium Ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) | Standard redox probe used in Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and EIS to characterize electrode performance and fouling resistance. |

Electrode fouling, the undesirable accumulation of material on electrode surfaces, is a major cause of performance degradation in redox flow batteries (RFBs) and other electrochemical systems, leading to increased resistance and capacity fade [26]. Layer-by-Layer (LbL) assembly presents a powerful nanoscale engineering strategy to construct tailored interfacial coatings that can mitigate this issue. This technique involves the sequential adsorption of oppositely charged materials, such as polyelectrolytes, to build up thin, conformal films on surfaces with precise control over composition and thickness [37] [38]. By creating a functional barrier, these polyelectrolyte multilayers (PEMs) can protect the electrode surface from foulants while maintaining essential electrochemical processes. This technical support center provides a practical guide for researchers implementing LbL coatings to combat electrode fouling in redox systems.

Core Principles & Reagent Toolkit

Physicochemical Foundations of LbL Assembly

The LbL technique is fundamentally driven by electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged polyelectrolytes, though other interactions like hydrogen bonding and host-guest interactions can also be employed [38]. The process relies on the self-assembly and self-organization of molecules at the nanoscale. A key consideration is the growth mechanism of the multilayer, which can be:

- Linear Growth: The film thickness increases by a constant amount with each deposited bilayer. This is typical for systems like poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) and poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS) assembled from low ionic strength solutions, resulting in stratified and compact films [38].

- Non-Linear (Exponential) Growth: The thickness increment per bilayer increases as the film grows, often due to polyelectrolyte diffusion within the film. This leads to thicker, more interpenetrated layers [38].

The choice of assembly conditions, including ionic strength, pH, and the chemical nature of the polyelectrolytes, dictates the growth regime and the final properties of the fouling-resistant coating.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials commonly used in LbL assembly for creating antifouling surfaces.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for LbL Assembly in Antifouling Applications

| Reagent Name | Function / Role in LbL | Common Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polycationic Solutions | Provides a positively charged layer; often the first layer on negatively charged substrates. | Branched Polyethyleneimine (PEI): High charge density, promotes adhesion. Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDADMAC): Strong cationic polyelectrolyte. Poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH): Commonly paired with PSS [37]. |

| Polyanionic Solutions | Provides a negatively charged layer; alternates with polycations to build the multilayer. | Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS): Standard strong polyanion, often used with PEI or PAH [39] [37]. Poly(acrylic acid) (PAA): A weak polyelectrolyte whose charge can be tuned by pH. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (Salt) | Modulates chain conformation and film structure; critical for controlling thickness and porosity. | Sodium Chloride (NaCl): Most common salt used to adjust ionic strength during polymer dissolution [37] [40]. |

| pH Adjustment Solutions | Tunes the charge density of weak polyelectrolytes, directly impacting layer interpenetration and film growth. | Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) / Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH): Used to adjust the pH of polyelectrolyte solutions [40]. |

| Substrate Preparation | Creates a uniformly charged surface to initiate the LbL process. | Oxygen Plasma, Piranha Solution, or Strong Alkali (e.g., NaOH): Used to clean and introduce charged functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH) on substrates like stainless steel or polymers [40] [41]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my LbL film growth inconsistent or non-uniform across the electrode surface? A: Inconsistent growth is frequently linked to inadequate substrate preparation or insufficient rinsing between deposition steps. Ensure your electrode substrate is thoroughly cleaned and carries a uniform surface charge before beginning assembly. For carbon-based electrodes, plasma treatment can be highly effective. Furthermore, ensure each rinsing step (typically with deionized water at the same pH as the polyelectrolyte solutions) is thorough enough to remove all loosely adsorbed polyelectrolyte chains, preventing cross-contamination between layers [40].

Q2: How does the ionic strength of the polyelectrolyte solution affect my final coating? A: Ionic strength is a critical parameter. Adding salt (e.g., NaCl) screens the electrostatic repulsion between charged segments on the same polyelectrolyte chain, causing it to adopt a denser, coil-like conformation in solution. When adsorbed, this leads to thicker, rougher, and more porous individual layers. For instance, assembling PSS/PAH from a 2 M NaCl solution can result in a much thicker and potentially more permeable film compared to assembly from a 0.5 M NaCl solution, which is relevant for controlling ion transport in redox systems [37].

Q3: Can LbL assembly be automated or scaled for large-area electrodes? A: Yes, traditional dip-coating can be challenging for large, porous substrates. Spray- and spin-assisted LbL assembly have been developed to address these limitations. Spray-assisted LbL significantly reduces processing time and can handle larger areas, while spin-assisted LbL produces very uniform and thin films. A combined spin-spray technique has been shown to produce high-quality nanofiltration membranes with competitive performance, demonstrating the scalability of the method for functional coatings [39].

Q4: My LbL-coated electrode shows high electrical resistance. How can I improve proton conductivity? A: High resistance often stems from a film that is too dense or thick. To enhance proton transport through the multilayer, you can:

- Reduce the number of bilayers to create a thinner barrier.

- Assemble the films from solutions with lower ionic strength to create denser, thinner layers with potentially different transport properties.

- Incorporate conductive nanomaterials, such as graphene oxide (GO), into the multilayers to create conductive pathways. The choice of polyelectrolyte pair also matters; for example, highly charged, rigid polymers like PSS can create different transport environments compared to more flexible chains.

Advanced Troubleshooting: Performance Fade

Table 2: Troubleshooting LbL Coatings for Redox Flow Battery Electrodes

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution & Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Capacity Fade | Physical degradation of the LbL coating (delamination, cracking). | Use SEM to inspect coating morphology before/after cycling. | Increase adhesion by optimizing the first layer (e.g., use a high-affinity polyelectrolyte like PEI). Ensure substrate is perfectly clean and charged. |

| Chemical degradation of polyelectrolytes in harsh redox environment. | Perform FTIR or XPS on coated electrodes after testing to detect chemical changes. | Select more chemically stable polyelectrolytes (e.g., PSS is often chosen for its stability). | |